In the early 1900s, a hidden world existed across the American South. It was a world of company towns, where the cotton mill owned everything: the small wooden houses the workers lived in, the single store where they bought their food, and the very future of the families who toiled there. Driven from failing farms by poverty, entire families came to these villages seeking survival. That survival depended on a brutal calculation: everyone had to work, including the youngest children. Their tiny hands were essential cogs in the deafening, dust-choked machine of America’s textile boom.

Children of the Looms

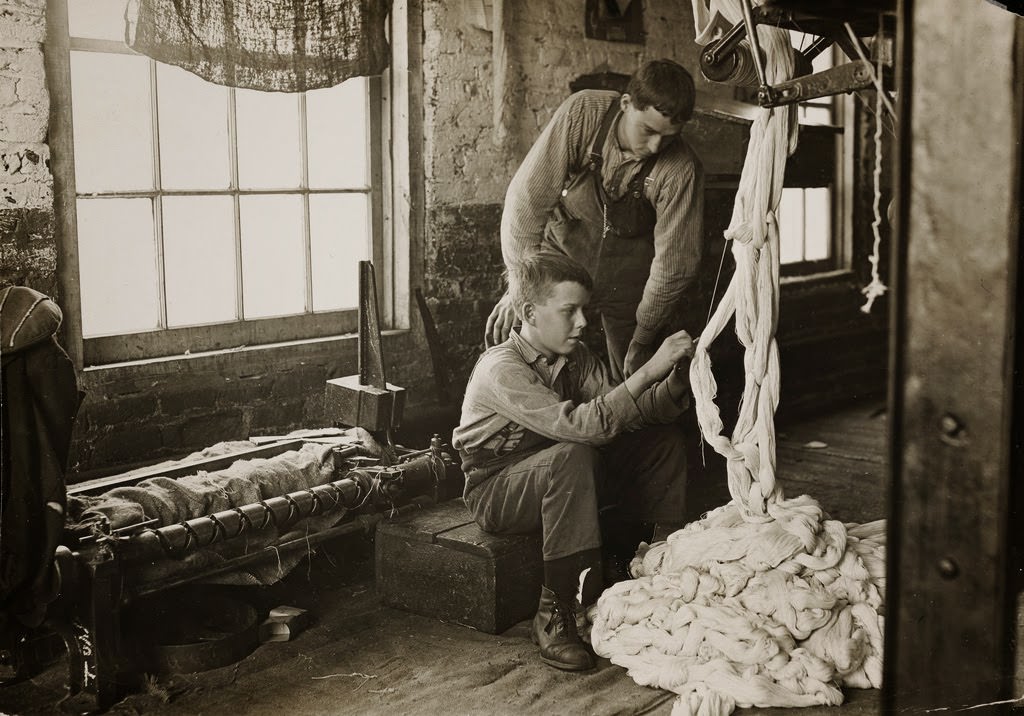

The moment you stepped inside a cotton mill, you entered a different reality, a thunderous landscape of machinery where children moved with a skill and weariness that defied their age. They weren’t just helping out; they performed specific, vital jobs that kept the massive operation running.

The youngest boys were often doffers. Their job was to run down the aisles of spinning frames, pull off the bobbins that were full of thread, and replace them with empty ones. This wasn’t a task done when the machines stopped. They had to perform this swap with lightning speed while the machinery was still running, a blur of small hands working amidst whirring gears and slapping leather belts. A moment’s hesitation or a clumsy move could mean a mangled hand.

Read more

Young girls were typically spinners. They spent their entire day on their feet, pacing up and down endless rows of spinning frames, covering miles of hard, oil-slicked wooden floors. Their job was to watch for breaks in the hundreds of threads spinning simultaneously. When a thread snapped, a girl would rush over and, with practiced dexterity, tie it back together using a special knot. It was monotonous, exhausting work in a constantly vibrating, overwhelmingly loud environment.

The lowest-status job, often given to the smallest children, was that of a sweeper. They carried heavy, bristled brooms, sweeping the thick layers of cotton dust and lint from the floors. This often required them to crawl into the tight spaces beneath the massive, active machinery, dodging moving parts in the dim light to keep the work area clean.

A World of Dust and Danger

Life in the mill was a constant assault on the senses and the body. The noise was the first thing you would notice—a deafening, relentless roar from hundreds of looms and spinning frames all running at once. The sound was so overpowering that workers couldn’t speak to each other; they communicated through shouting or hand signals. Many workers developed hearing loss over time.

Worse than the noise was the air itself. The atmosphere was thick with a fog of cotton dust and lint that hung in the air and covered every surface. Children breathed this in, hour after hour, day after day. This led to a chronic lung condition known as byssinosis, or “brown lung,” which started with a persistent cough and often progressed to permanent disability and breathing problems.

The physical danger was immediate and ever-present. The machinery was a maze of exposed gears, belts, and pulleys with no safety guards. A piece of loose clothing, a strand of hair, or a tired, careless hand could be snatched in an instant. Horrific accidents were a common part of life, resulting in crushed fingers, mangled limbs, and sometimes death. The long hours—typically 10 to 12 hours a day, six days a week—compounded the danger, as exhaustion made children more vulnerable to mistakes.

The Man with the Camera

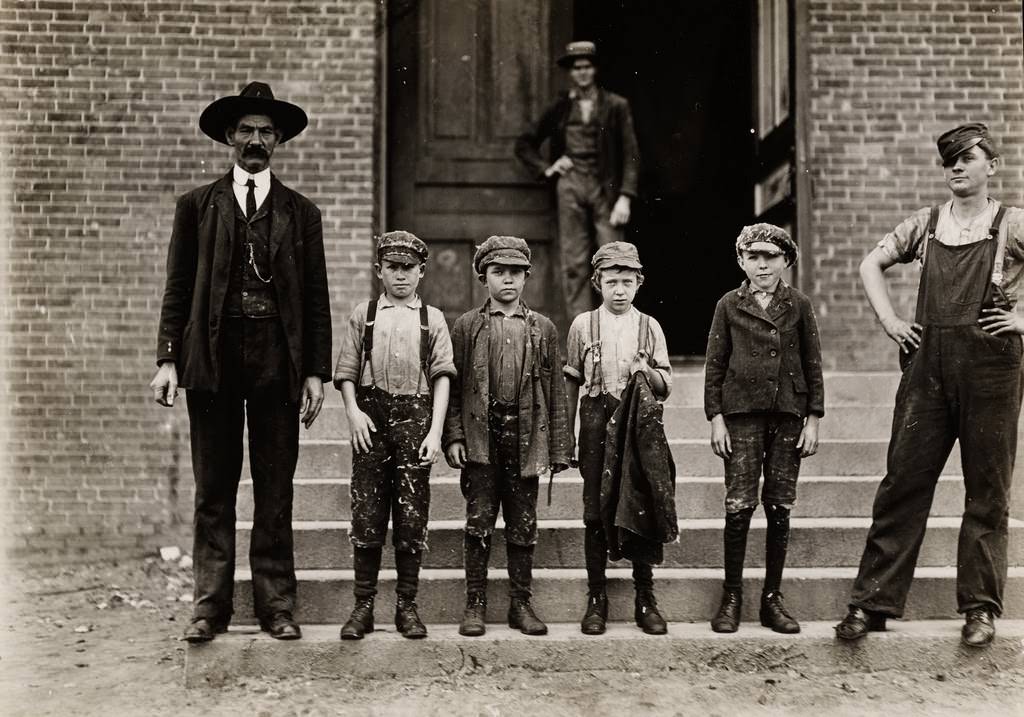

This hidden world of child labor might have remained largely invisible if not for one man: Lewis Hine. A photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), Hine traveled across the country in the early 1900s with a mission to document the reality of child labor. Mill owners knew that public knowledge of their practices would bring trouble, so they banned photographers. Hine had to be clever.

He posed as a fire inspector, an insurance salesman, or even a postcard vendor to gain access to the mills. Once inside, he worked quickly. He would talk to the children, secretly scribbling notes on a pad hidden in his pocket. He recorded their names, their ages, and how long they had worked. To prove how young they were, he would often photograph them standing next to the machinery, using the machine’s height as a scale to show how small the child was.

His photographs were revolutionary. They weren’t just pictures; they were undeniable proof. He captured the defiant stares, the exhausted slumps, and the grime-covered faces of children who looked old before their time. One of his famous images shows a tiny girl named Sadie Pfeifer, a spinner who was so small she had to stand on a wooden box to reach her machine. Hine’s captions were stark and factual: “Sadie Pfeifer, 48 inches high. Has been in the mill one year. One of the many small children at work in Lancaster Cotton Mills.”

A System of Traps

The system was designed to keep families tied to the mill. Many companies paid their workers in scrip, a type of credit that could only be used at the company-owned store. Families called this the “pluck-me store” because the prices were inflated, ensuring that workers were always in debt to the company that employed them. This debt made it impossible to leave.

Education was a distant dream. While some states had laws requiring children to attend school, they were weak and rarely enforced in mill towns. Mill owners would often claim the children were “helping” their parents or that the work itself was a form of vocational training. The reality was that a child’s education ended the day they started work. Many of these young workers grew up unable to read or write, limiting their chances of ever escaping the mill life. This isolation was reinforced by social stigma. Outsiders often looked down on the mill families, calling them by the derogatory name “lintheads” because their hair and clothes were constantly covered in cotton dust.

The children of the mills were trapped in a cycle of poverty and labor. A typical day for a young doffer might begin before sunrise, followed by a 12-hour shift in the thunderous, suffocating environment of the spinning room. At the end of the day, covered from head to toe in a fine layer of white lint, he would trudge back to the small company house, eat a meager dinner, and fall into an exhausted sleep, only to wake up and do it all over again.