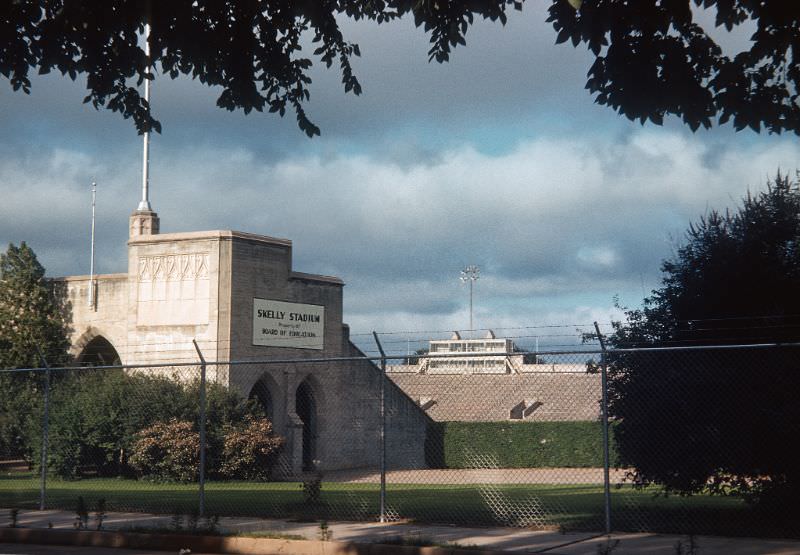

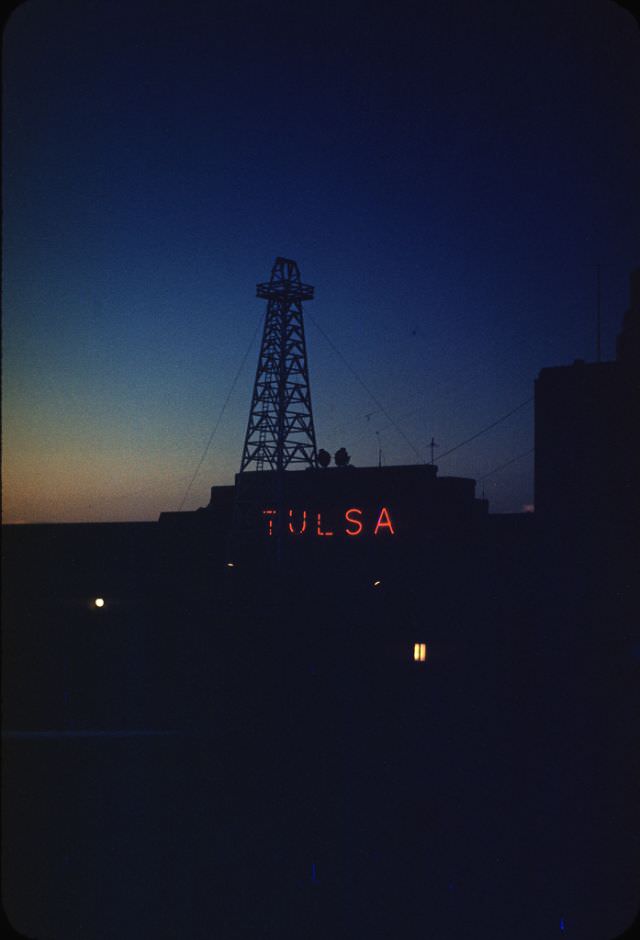

In the 1940s, Tulsa held the title of “Oil Capital of the World” securely. The city served as the headquarters for nearly every major oil company in the United States. Firms like Skelly Oil, Sinclair, and Phillips Petroleum managed their vast empires from downtown Tulsa. This concentration of wealth created a unique economy that remained strong even when other parts of the country struggled. Money from the oil fields funded public parks, museums, and grand estates in midtown.

The International Petroleum Exposition took place here, drawing thousands of visitors from across the globe. This massive trade show displayed the latest drilling technology and celebrated the industry that built the city. The expo grounds were a source of local pride, showcasing the Golden Driller statue which eventually became a permanent city icon.

The War Effort and Aviation

World War II transformed Tulsa’s industrial landscape almost overnight. The United States government selected the city for a massive new manufacturing facility. The Douglas Aircraft Company plant opened and began producing B-24 Liberator bombers. This factory was nearly a mile long and employed thousands of workers, including many women who entered the industrial workforce for the first time.

The arrival of the bomber plant solved any lingering unemployment issues from the Great Depression. It also spurred a housing shortage. Workers flooded into the city, filling boarding houses and new developments. Tulsa Municipal Airport became one of the busiest in the nation during these years, serving as a hub for military transport and pilot training.

Read more

An Art Deco Skyline

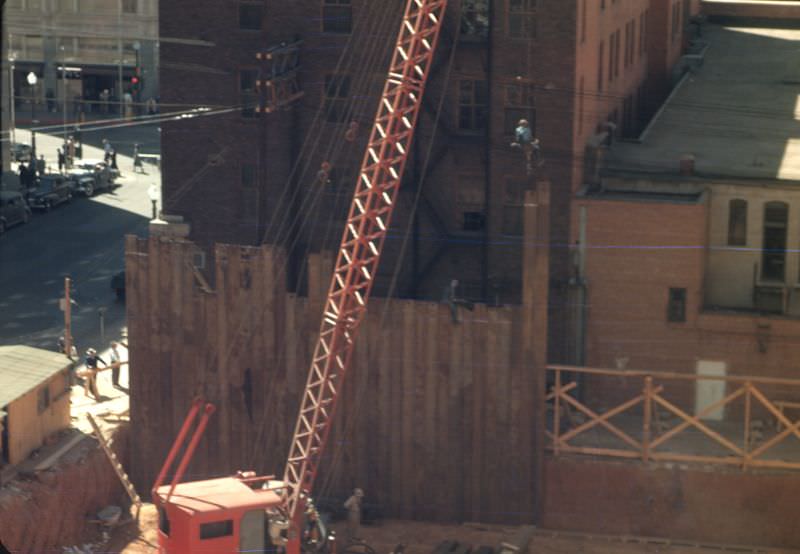

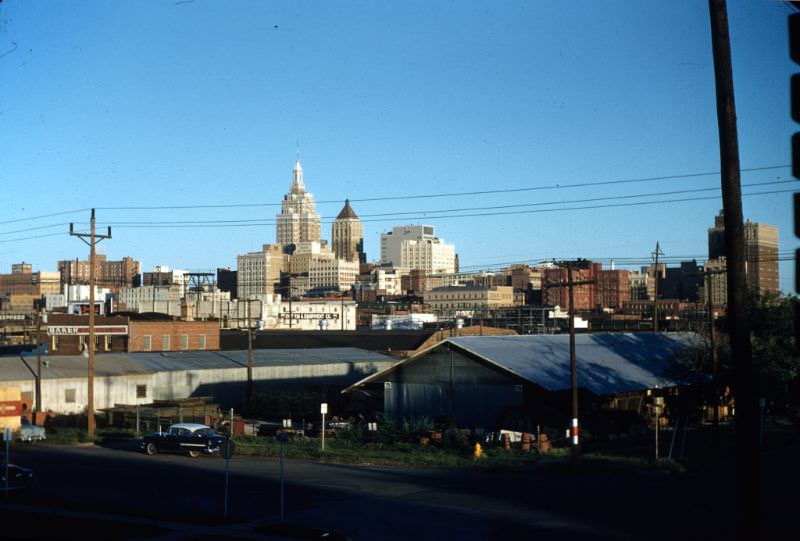

Downtown Tulsa in the 1940s and ’50s looked distinctively modern. The oil boom of the previous decades financed a skyline filled with Art Deco architecture. Buildings like the Philtower and the Philcade defined the city center with their geometric designs and ornate details. The Boston Avenue United Methodist Church stood as a towering example of this style, recognized nationally for its unique appearance.

Underground tunnels connected many of these downtown skyscrapers. Businessmen used these tunnels to move between offices and hotels without facing the summer heat or winter cold. The streets above bustled with activity. Streetcars and buses moved crowds of office workers, while department stores like Vandever’s and Brown-Dunkin drew shoppers to Main Street.

Route 66 and the Drive-In Era

As the 1950s arrived, the automobile reshaped the city’s layout. Route 66 ran directly through Tulsa on 11th Street, bringing a steady stream of travelers. Motels, diners, and gas stations sprang up along this corridor to service the traffic. The neon signs of the Meadow Gold dairy and various motor courts lit up the night, creating a vibrant strip of commerce.

Teenage culture flourished in this car-centric environment. The Admiral Twin Drive-In opened in the early 1950s, becoming a major social hub. It featured two massive screens and held hundreds of cars. Families and teenagers spent their evenings there, ordering food from carhops and watching the latest Hollywood films.

Suburban Expansion

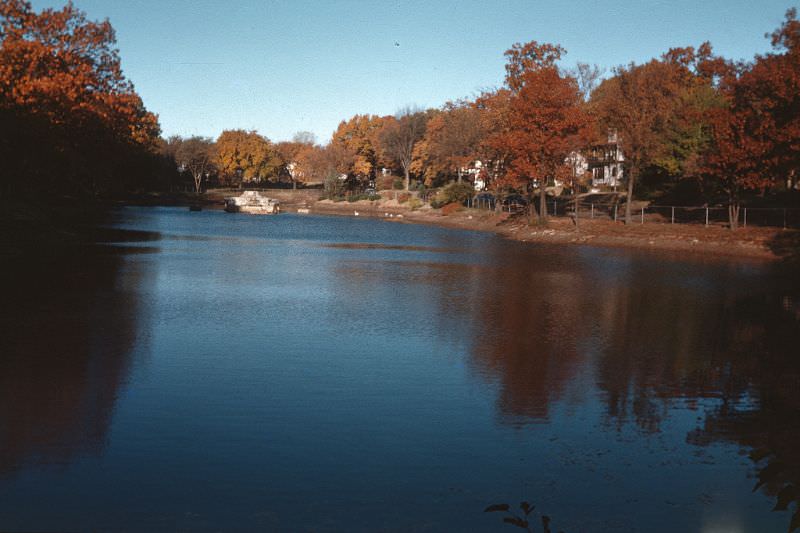

The end of the war and the return of soldiers triggered a building boom in the 1950s. The city expanded rapidly to the south and east. Ranch-style houses replaced open farmland. Neighborhoods like Lorton Lake and Patrick Henry emerged to house the growing middle class. Shopping centers, such as Utica Square, opened to serve these new suburban residents, drawing retail business away from the downtown core.

These new subdivisions featured wide streets, large lawns, and modern schools. The focus of daily life shifted from the city center to the neighborhood. Backyard barbecues and community pools became the standard for social interaction in these areas.