In the 1950s, Washington D.C. was the undisputed capital of the “Free World.” It was a city of gleaming white marble monuments, a powerful nerve center from which America projected its strength and ideals across the globe. But beneath the polished veneer of global power, another Washington existed. It was a city humming with the paranoia of the Cold War, a place of deep racial divides, and the epicenter of a massive social shift that was emptying the city center and building a new kind of American Dream in the suburbs. This was a decade of immense confidence and deep-seated anxiety, all playing out on the streets of the nation’s capital.

The Cold War’s Front Line

Nowhere in America was the Cold War felt more intensely than in Washington. This wasn’t a distant conflict; it was a daily reality that shaped every aspect of life. The fear of communism, fanned by politicians like Senator Joseph McCarthy, created a “Red Scare” that permeated the federal government. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) held dramatic hearings, and government employees, artists, and academics could have their lives and careers destroyed by a single accusation of having communist sympathies. A climate of suspicion settled over the city.

The threat of nuclear war was equally real. Schoolchildren were routinely drilled in “duck and cover” exercises, practicing how to hide under their desks in the event of an atomic blast. Air raid sirens were tested regularly across the city, a chilling reminder of the ever-present danger. Washington was a prime Soviet target, and everyone knew it.

Read more

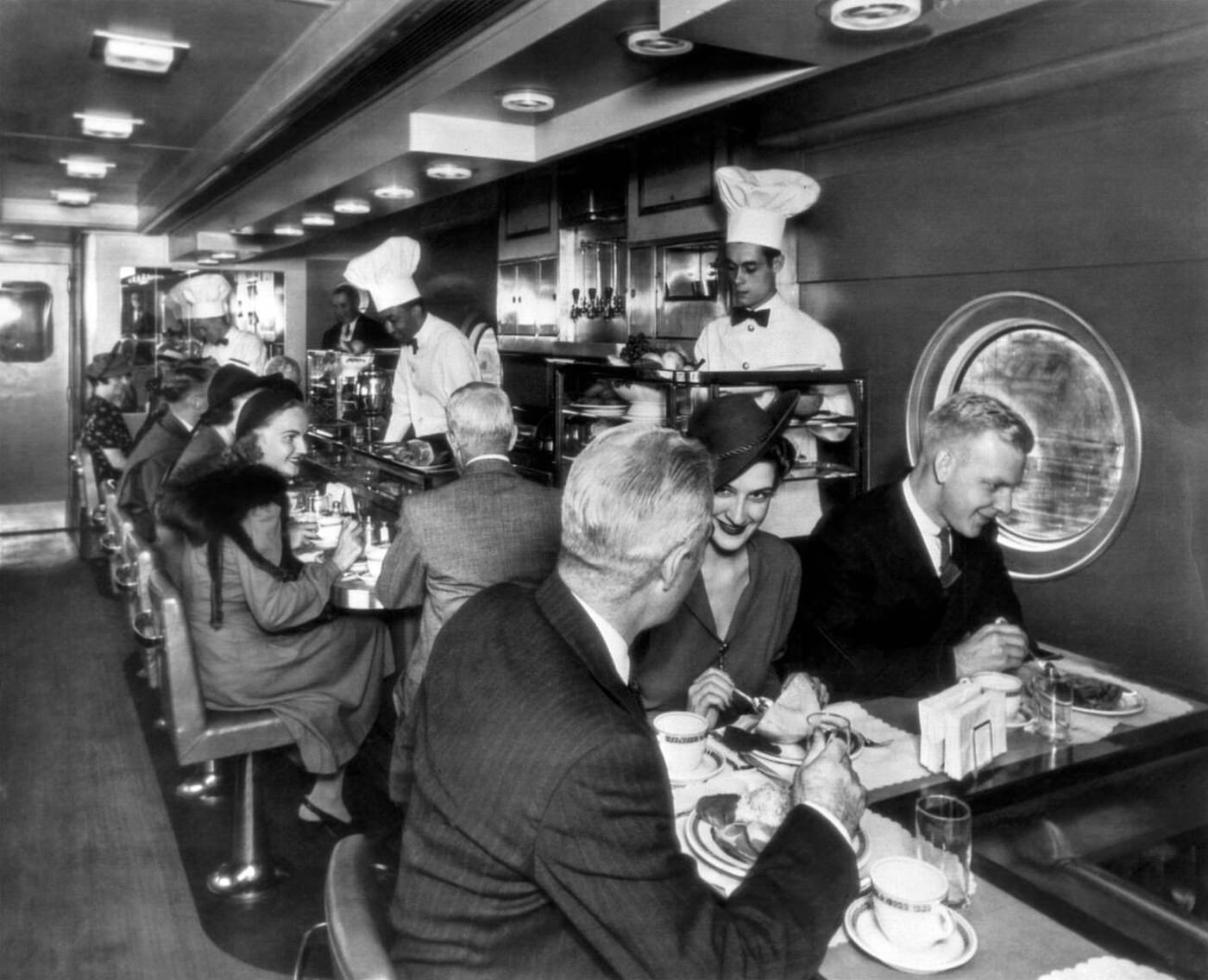

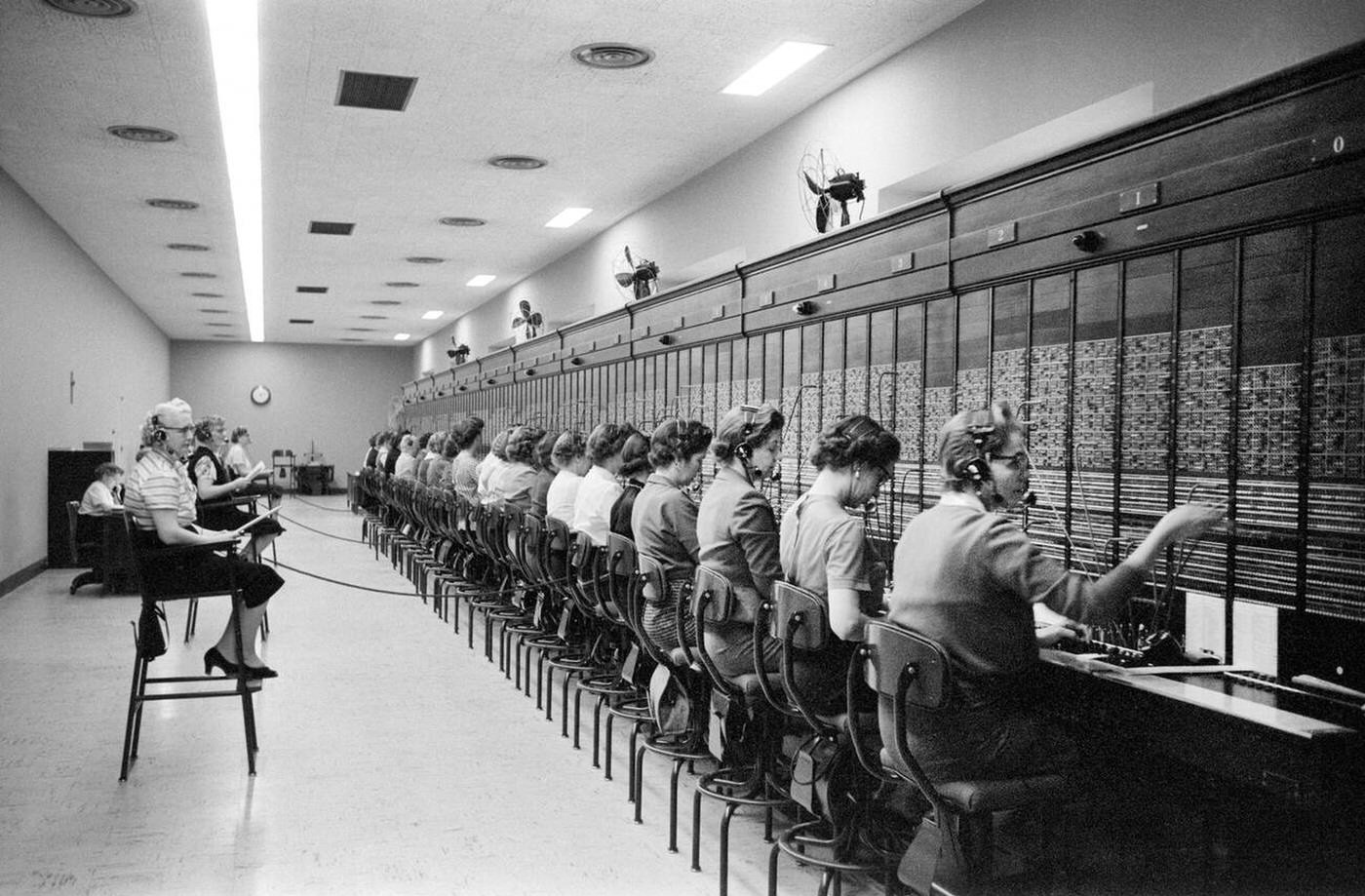

This constant state of high alert fueled a massive expansion of the federal bureaucracy. The Pentagon, the world’s largest office building, was the heart of a sprawling military-industrial complex. Thousands of people flocked to the region for government jobs, filling the city with a bustling population of clerks, diplomats, military officers, and spies. The city was a magnet for the ambitious, the patriotic, and the paranoid.

Chocolate City, Vanilla Suburbs: A Capital Divided

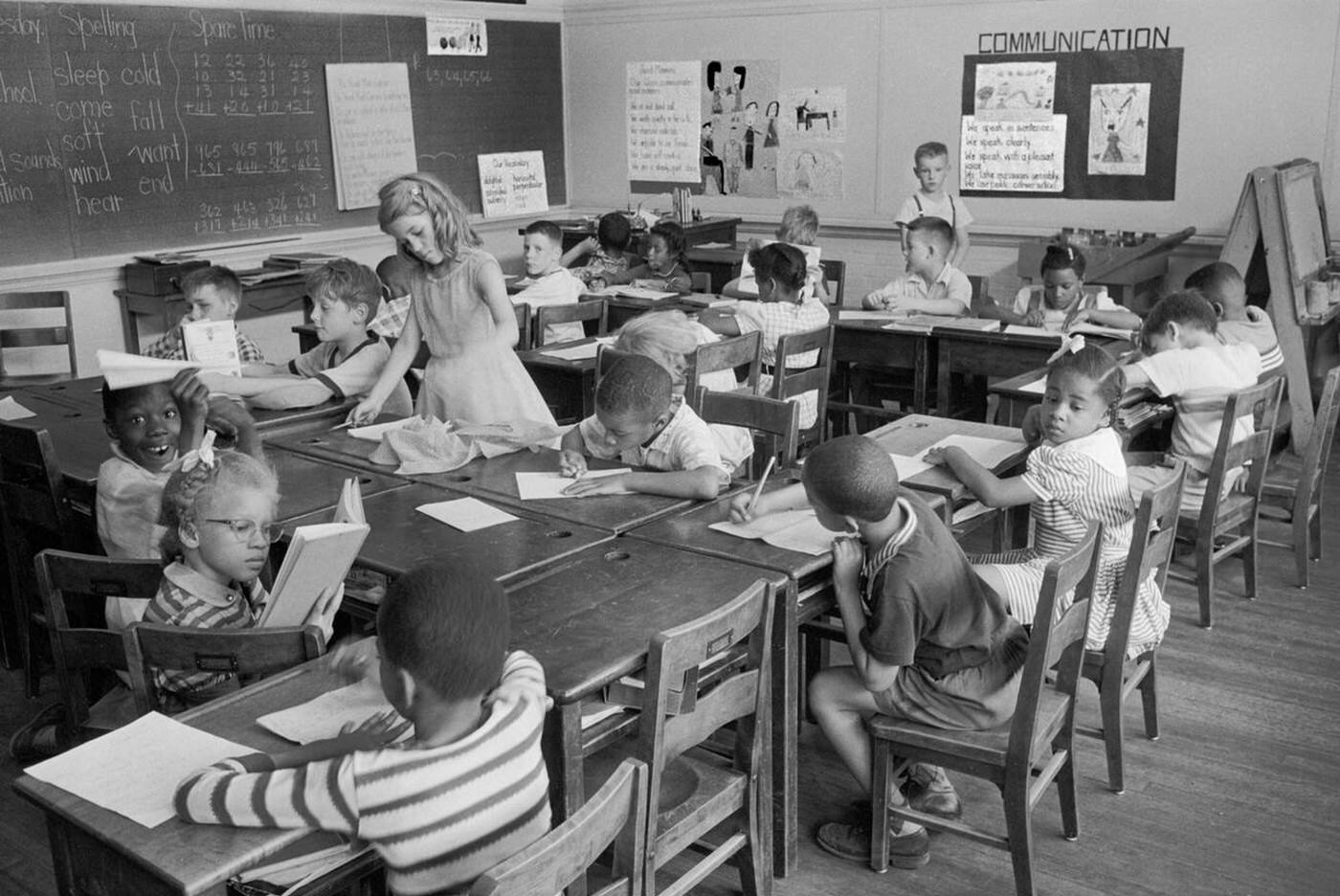

While America broadcast a message of freedom to the world, its own capital city was a place of deep and legal segregation. In the early 1950s, Black and white residents lived in two different Washingtons. Public schools, by law, were separated by race. Many restaurants, movie theaters, hotels, and even public parks were strictly segregated. A Black family could not simply go to any lunch counter or take their kids to the popular Glen Echo Amusement Park.

During this decade, Washington underwent a profound demographic transformation. It was a major destination for African Americans moving from the rural South in the Great Migration, seeking opportunity and escaping the harsher realities of Jim Crow. This influx, combined with a mass exodus of white families to the suburbs, led to a historic shift. In 1957, Washington D.C. became the first major American city to have a majority Black population.

This “white flight” was fueled by new highways and federally backed mortgages that made buying a house in the suburbs easier than ever for white families. The result was the famous dynamic of a “chocolate city and vanilla suburbs.”

Despite the barriers of segregation, Black Washington pulsed with a vibrant cultural life of its own. The U Street corridor in Northwest D.C. was the heart of this world, known as “Black Broadway.” It was a thriving district packed with Black-owned businesses, elegant restaurants, and legendary music venues like the Lincoln Theatre and Howard Theatre. Jazz giants like Duke Ellington, who grew up in D.C., helped create a world-class music scene that made U Street a cultural capital in its own right.

The Suburban Dream and the Rise of the Car

The 1950s was the decade that the American Dream became synonymous with a house in the suburbs, and the D.C. region was a prime example. New communities with names like Silver Spring in Maryland and Arlington in Virginia sprang up, offering rows of single-family brick homes with green lawns and two-car garages. This was the picture of postwar prosperity.

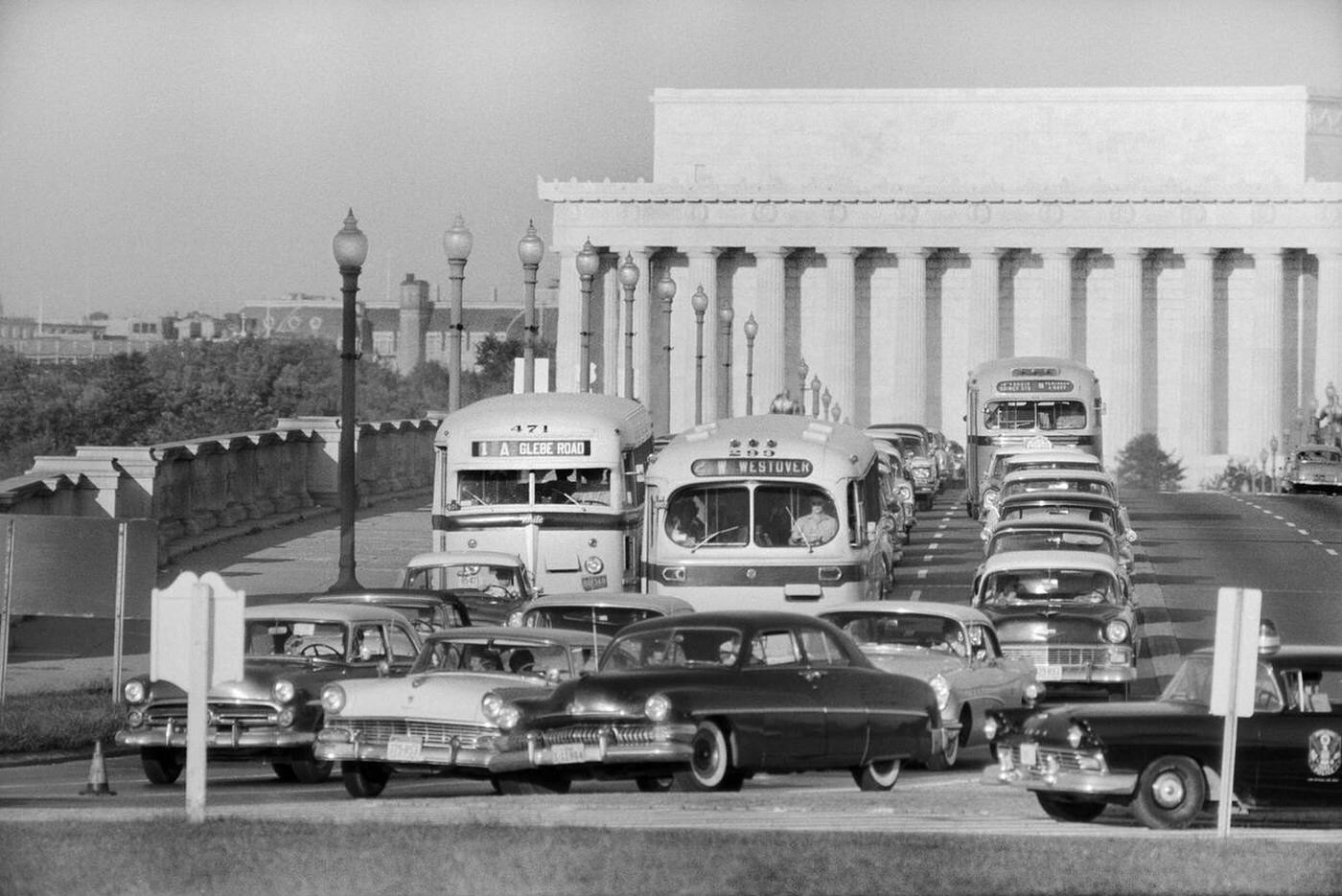

This new way of life was powered entirely by the automobile. The car was king. Massive highway projects were planned to connect the new suburbs to the city’s downtown core. The most ambitious of these was the Capital Beltway, a 64-mile ring road that would encircle the city, a concrete monument to the new car-centric culture.

This had a dramatic effect on the city itself. Downtown D.C., home to the grand government buildings of the Federal Triangle, increasingly became a place people drove to for work and then promptly left at 5 p.m. The rise of the suburban shopping mall, with its endless free parking, began to pull shoppers away from the traditional downtown department stores on F Street. The city was transforming from a place where people lived and worked into a place people simply worked.

Daily Life and Distractions

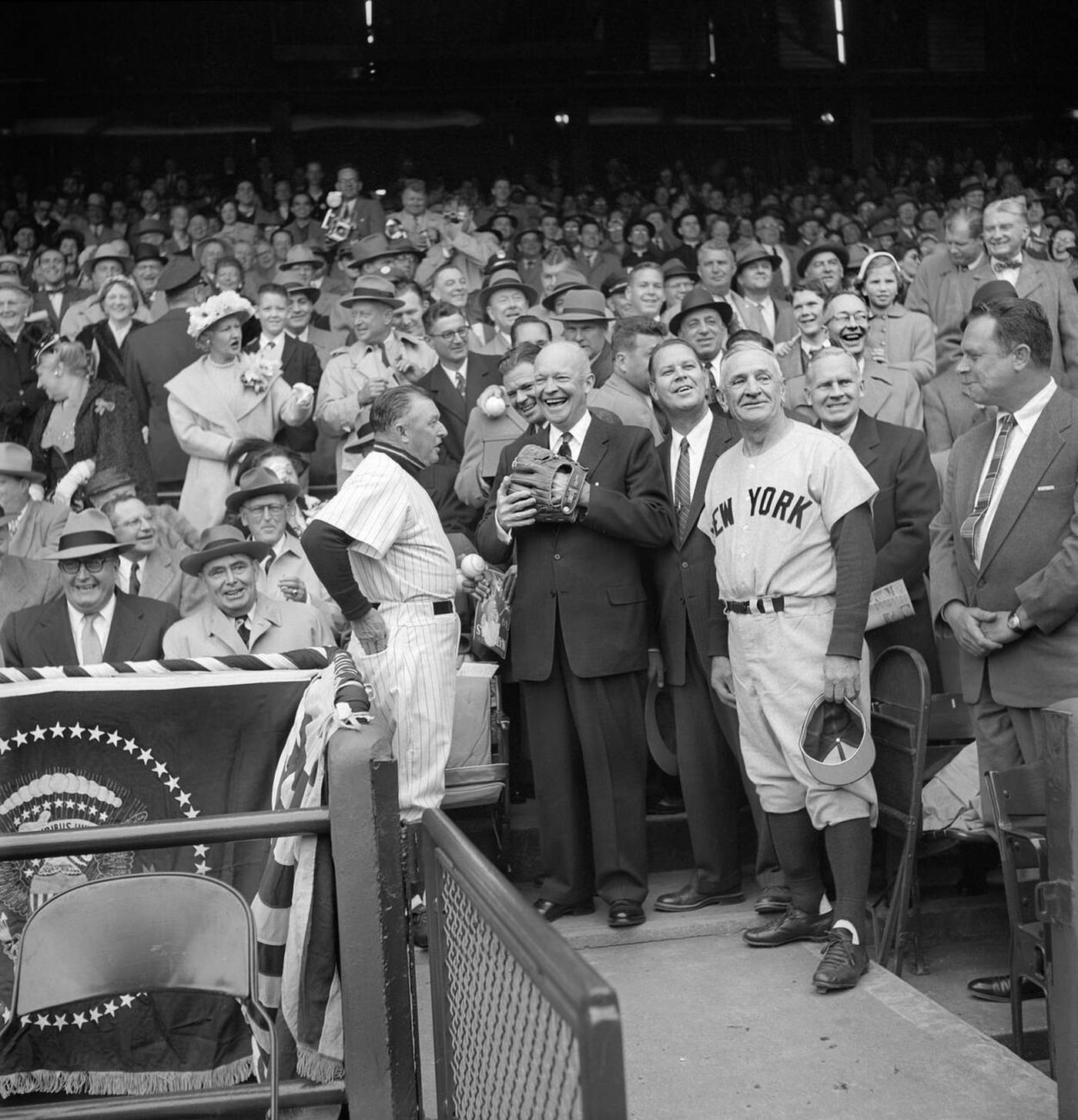

Amidst the global tensions and social shifts, life went on. For entertainment, Washingtonians could head to Griffith Stadium to watch the Washington Senators play baseball. The city’s pro football team, the Washington Redskins, also played there, though the team remained stubbornly segregated, becoming the very last in the NFL to integrate in 1962, and only after intense pressure from the federal government.

Downtown was home to a strip of grand “movie palaces,” ornate theaters that offered an escape into the glamour of Hollywood. But a new form of entertainment was taking over. This was the golden age of television, and families across the region gathered around their small, black-and-white sets to watch hit shows like I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners.

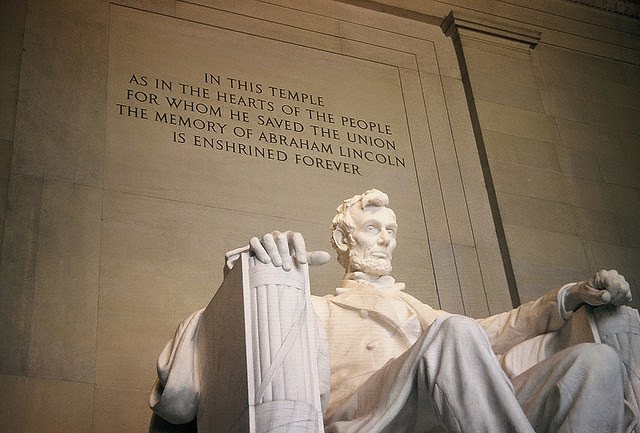

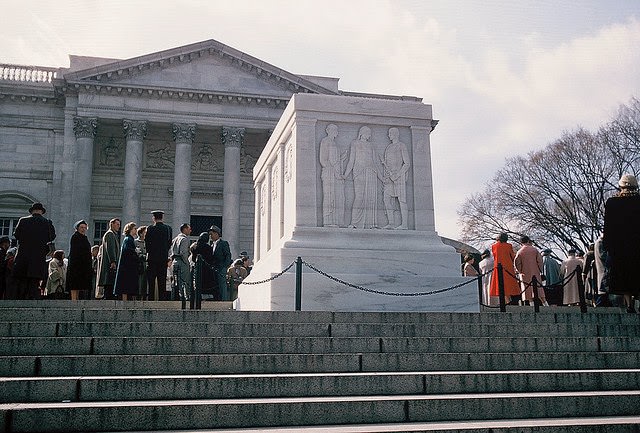

And through it all, the city’s iconic monuments stood as silent witnesses. The Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument, and the Capitol Building formed a majestic, unchanging backdrop to the capital’s turbulent decade. They were a destination for tourists taking photos with their Brownie cameras and a powerful stage for the stirrings of the civil rights protests that would soon sweep the nation. A family might pile into their big, tail-finned Chevrolet in a quiet suburban driveway, leaving their new home to drive into the city. The kids might be thinking about the “duck and cover” drills they practiced at their new school, while their parents navigated a capital that was both the powerful epicenter of the free world and a place deeply fractured by invisible lines of race and class, with the gleaming dome of the Capitol in the distance, a constant symbol of the ideals the city below was still fighting to fully realize.