The 1880s in Ireland were a decade of fire and fever. It was a time of immense suffering and poverty, but also of incredible hope and revolutionary change. This was not just one story, but many, all unfolding at once. On one front, tenant farmers waged a brilliant war of social resistance against their powerful landlords. On another, a political mastermind held the fate of the British government in his hands. And in towns and villages, a quiet cultural rebellion was beginning, as the Irish people started to reclaim the games, language, and soul that had been suppressed for centuries. This was the crucible where modern Ireland was forged.

The War for the Land

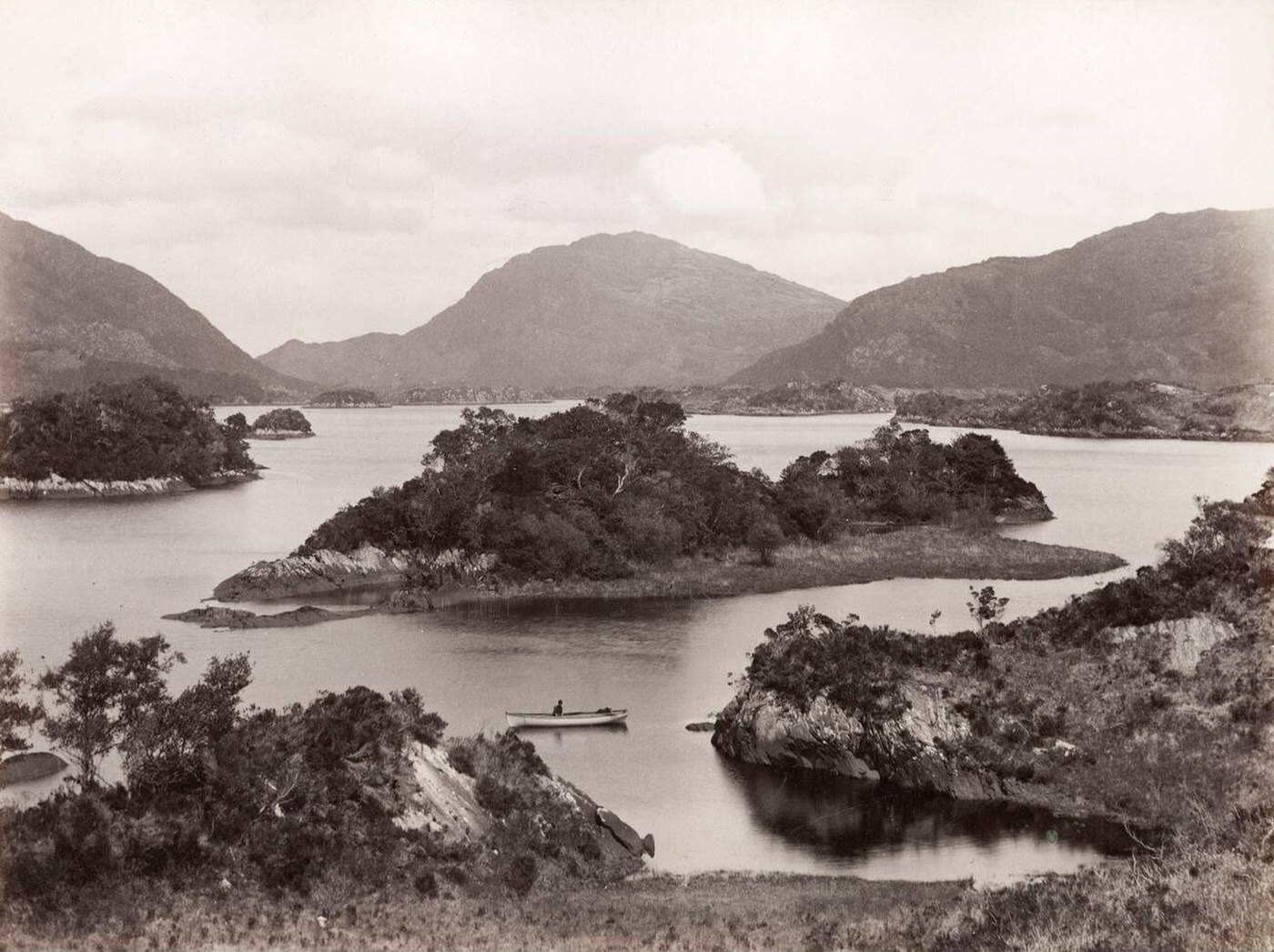

The most dominant and dramatic story of the 1880s was the Land War. In the aftermath of the Great Famine, most of the rural population were tenant farmers, living in crushing poverty on land owned by a small number of aristocrats. They had no rights and could be evicted on a whim. In the late 1870s, a crisis of bad harvests and collapsing prices led to mass eviction notices, pushing the people to the brink.

In response, the Irish National Land League was formed, led by the passionate organizer Michael Davitt and the brilliant politician Charles Stewart Parnell. They organized the people to fight back, not with guns, but with unity. They orchestrated massive rent strikes and physically blocked evictions, with entire communities turning out to defend a neighbor’s home.

Read more

Their most famous tactic gave a new word to the world. When a land agent in County Mayo, Captain Charles Boycott, tried to evict his tenants, the community, on Parnell’s advice, gave him the silent treatment. His workers quit, shops refused him service, and the postman wouldn’t deliver his mail. He was completely isolated. This new weapon of non-violent, organized shunning became known as boycotting. It was devastatingly effective. The British government was forced to listen, eventually passing the Land Act of 1881, which for the first time granted tenants rights and fair rents. The absolute power of the landlord was broken.

The Fight for the Nation: Parnell and Home Rule

The energy and organization of the Land War flowed directly into the political arena. The leader of the Irish people, Charles Stewart Parnell, became known as the “Uncrowned King of Ireland.” His goal was Home Rule—not full independence, but a devolved Irish parliament in Dublin that would manage Ireland’s domestic affairs, while still remaining part of the British Empire.

Parnell was a political genius. He led the Irish Parliamentary Party in London, and through the 1880s, he masterfully used his disciplined block of Irish MPs to hold the balance of power between Britain’s two main parties, the Liberals and the Conservatives. He would trade Irish support for political concessions, bringing Home Rule closer to reality than ever before.

This political maneuvering was nearly derailed by an act of shocking violence. In May 1882, members of a secret republican society called “The Invincibles” assassinated the two most senior British officials in Ireland as they walked through Dublin’s Phoenix Park. The murders horrified the public and threatened to destroy the credibility of the Irish nationalist movement. Parnell, who knew nothing of the plot, was forced to publicly condemn the killings to save the cause of Home Rule from being forever associated with terrorism.

The Soul of the Nation: The Gaelic Revival

While politicians fought in Westminster, another, quieter revolution was taking place in the fields and towns of Ireland. Many felt that centuries of British rule had eroded Ireland’s native culture, a process known as Anglicisation. A new generation of nationalists believed that for Ireland to be truly free, it had to be culturally Irish.

This led to the Gaelic Revival. A key moment was the founding of the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) in 1884. Its mission was to organize and promote traditional Irish sports like hurling and Gaelic football. This was a direct cultural challenge to English games like cricket and soccer, which were popular with the British army and administration. The GAA provided a powerful network for nationalists at a grassroots level, connecting a love of sport with a love of country.

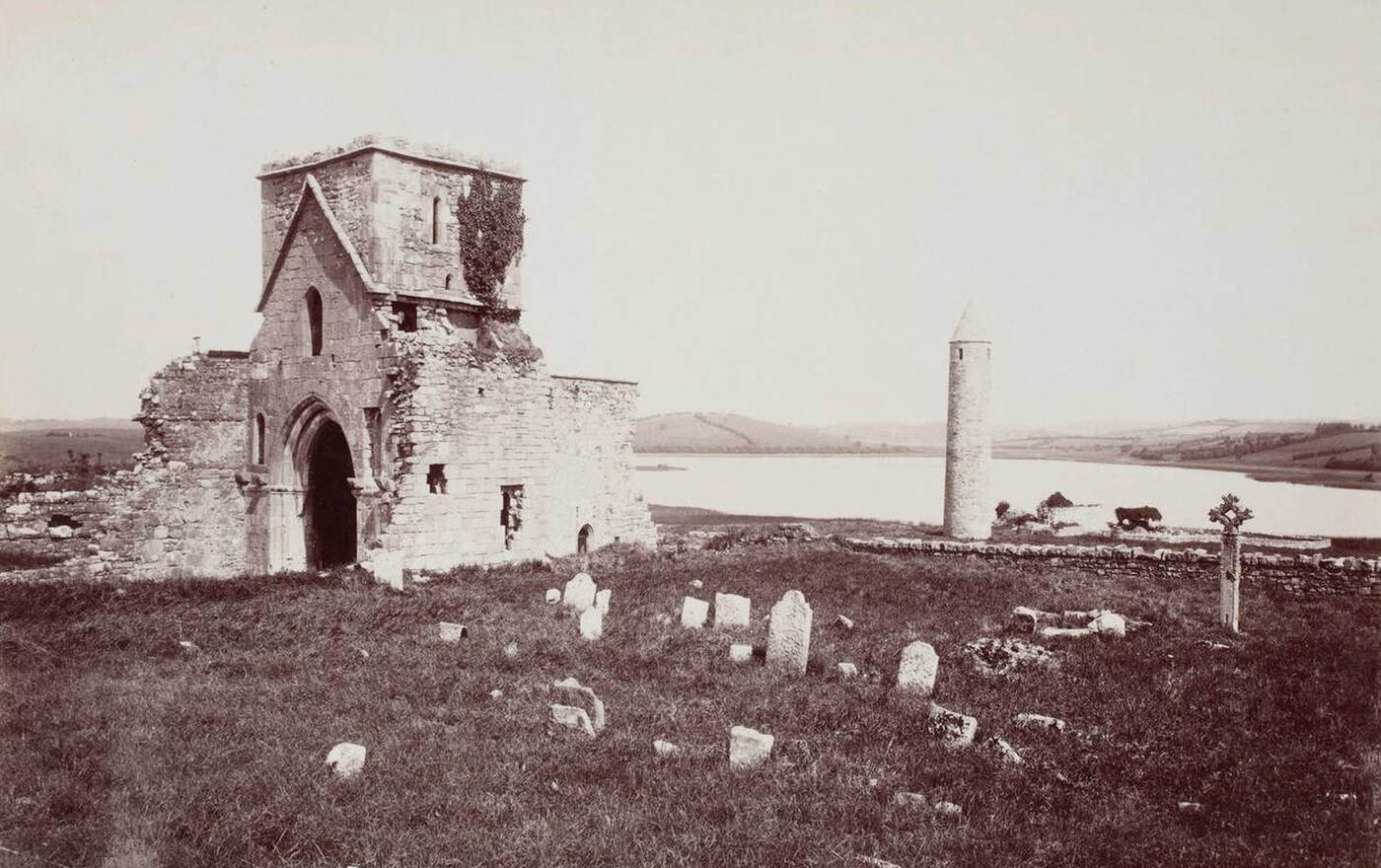

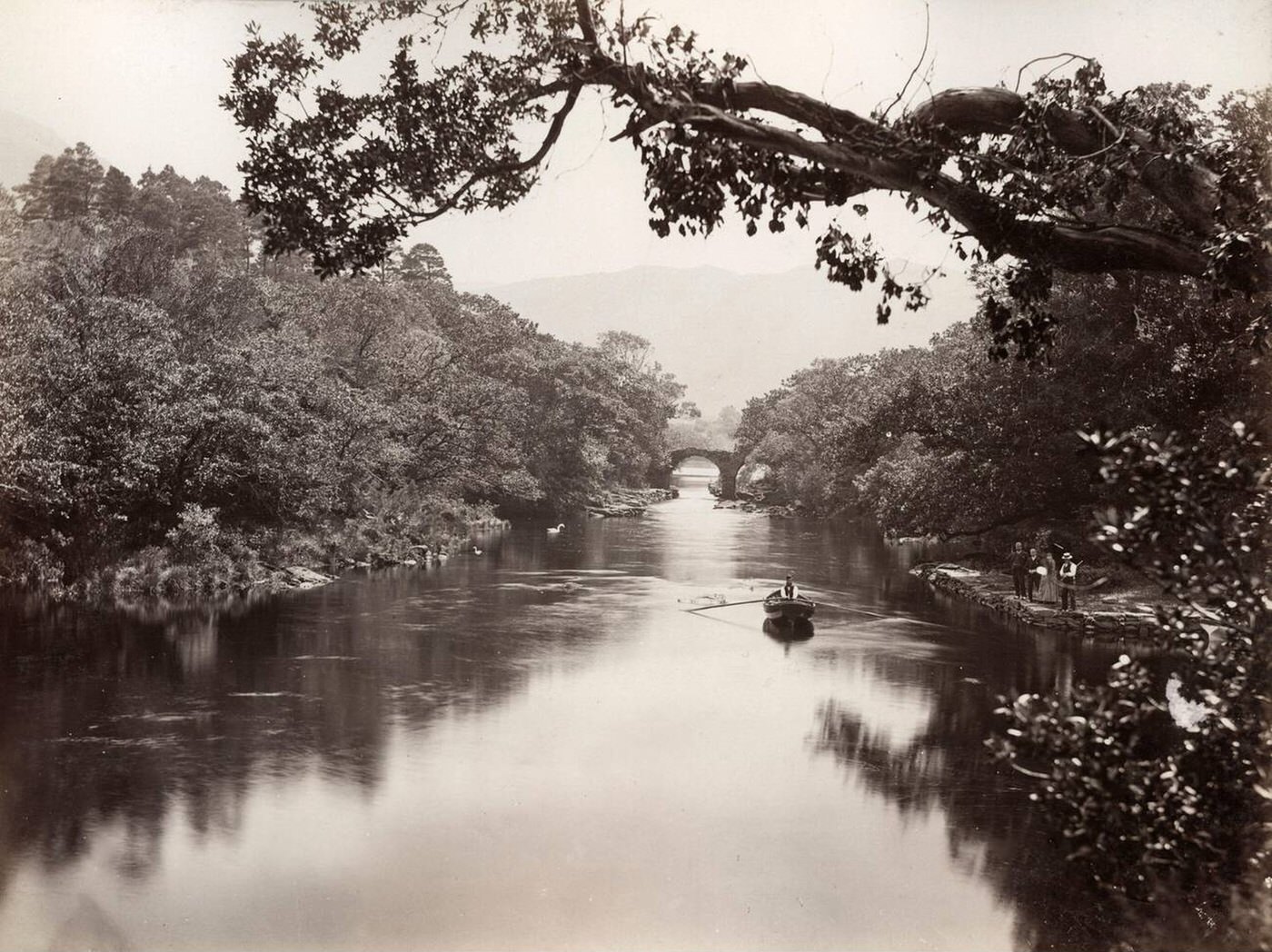

Alongside this sporting revival was a renewed interest in the Irish language (Gaelic). Scholars and enthusiasts began collecting folk tales from rural, Irish-speaking areas. The ancient myths of heroes like Cú Chulainn were retold, inspiring a new generation of poets and playwrights. This was about more than just nostalgia; it was a conscious effort to rediscover and reclaim a national identity that was distinct, ancient, and decidedly not English.

The Reality of Daily Life

For all the high drama of politics and culture, the daily reality for most people in 1880s Ireland remained incredibly harsh. Poverty was widespread, and the shadow of the Famine was long. For thousands, the only hope for a better life lay across the Atlantic.

Emigration was a constant, heartbreaking drain on the country. Every year, ships packed with Ireland’s youth left for America, Canada, and Australia. The departure of a loved one was marked by a custom known as the “American wake.” It was a farewell party that felt like a funeral, a night of music, dancing, and tears, because everyone knew that they would almost certainly never see the person again. Letters from America, often containing precious dollars, were a vital link back to a lost world.

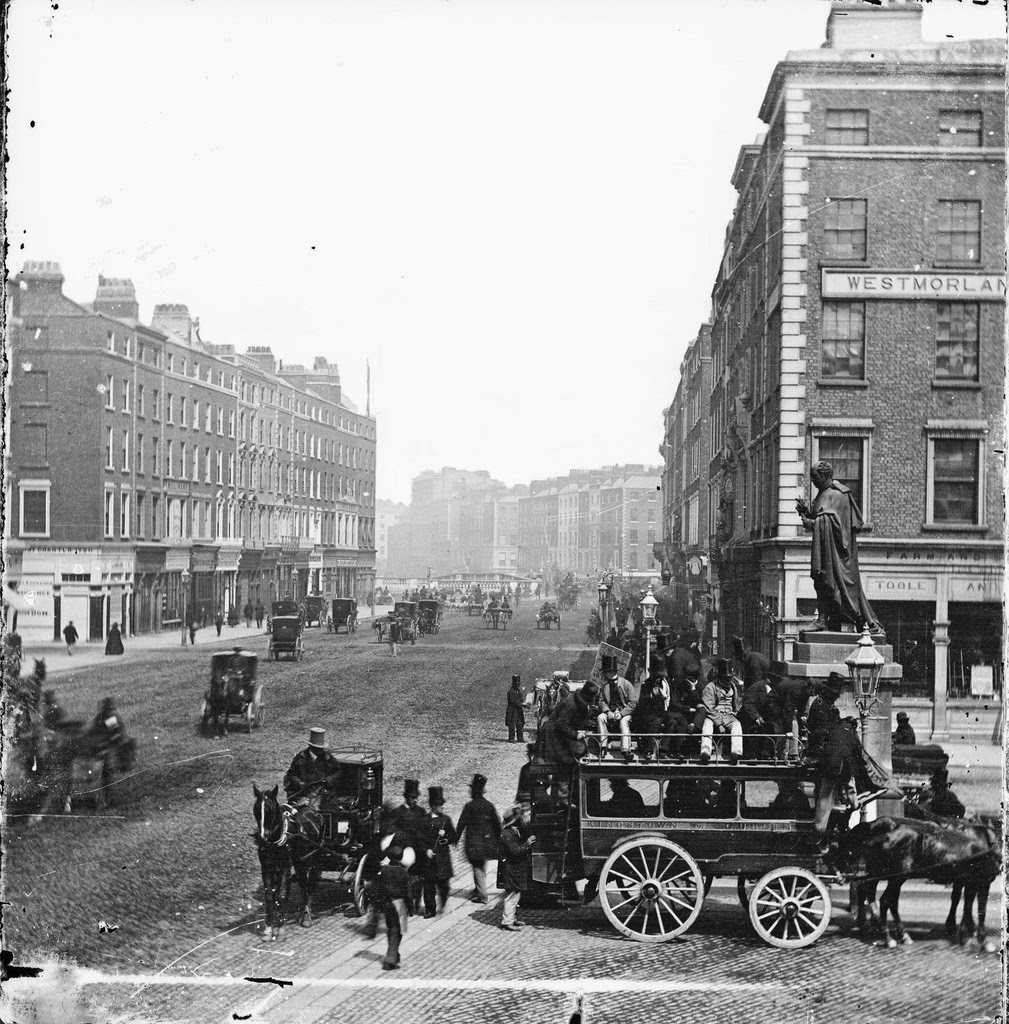

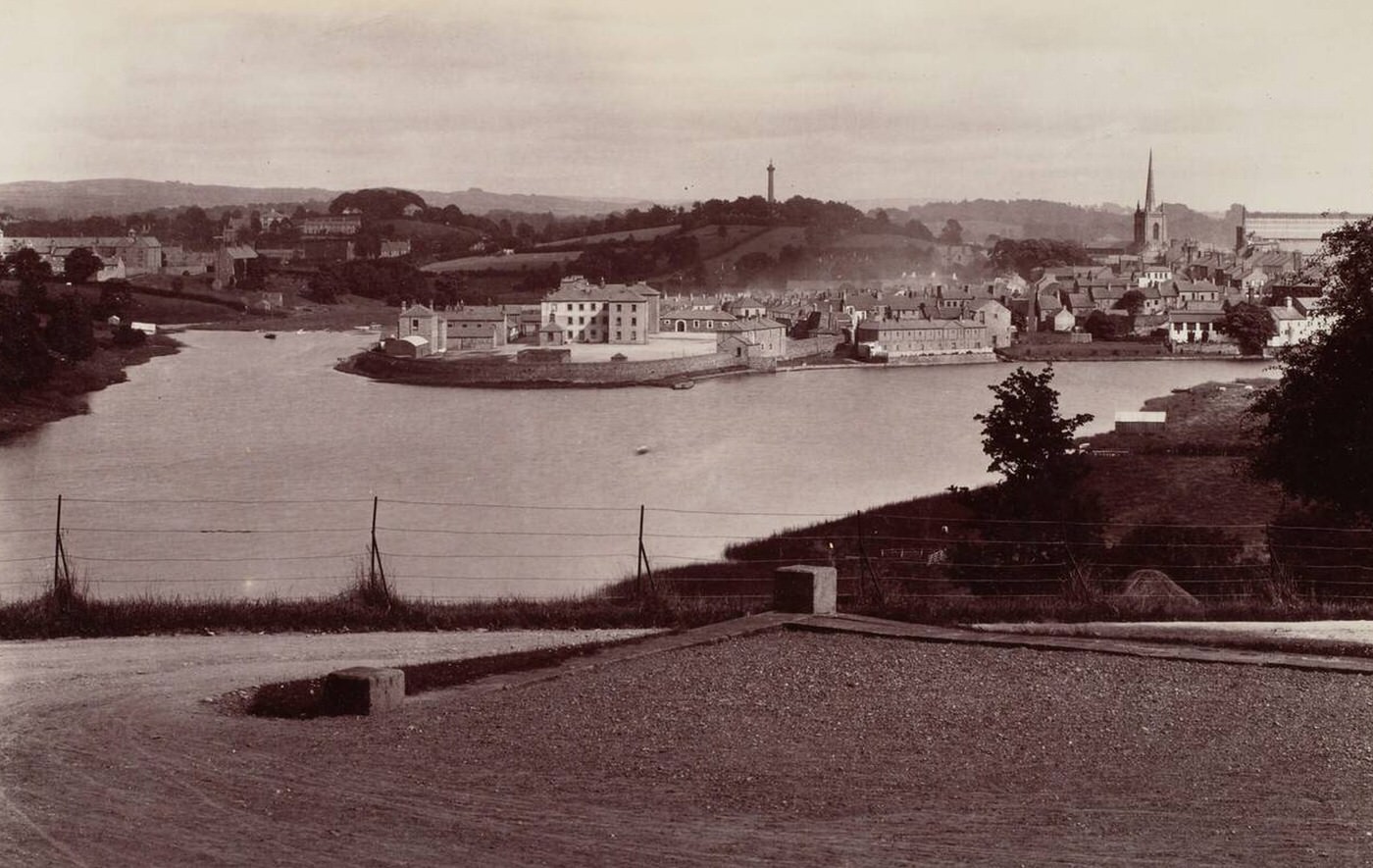

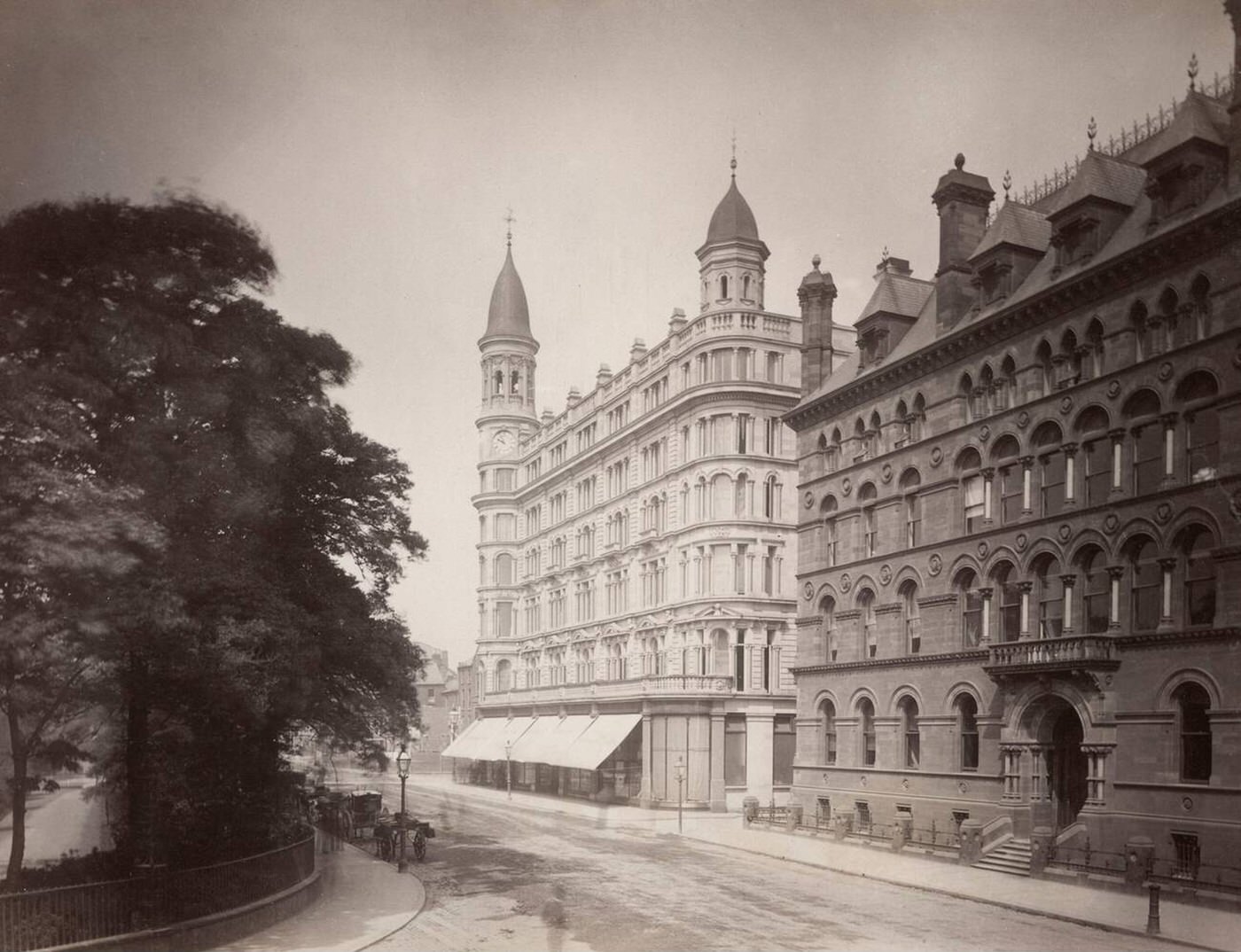

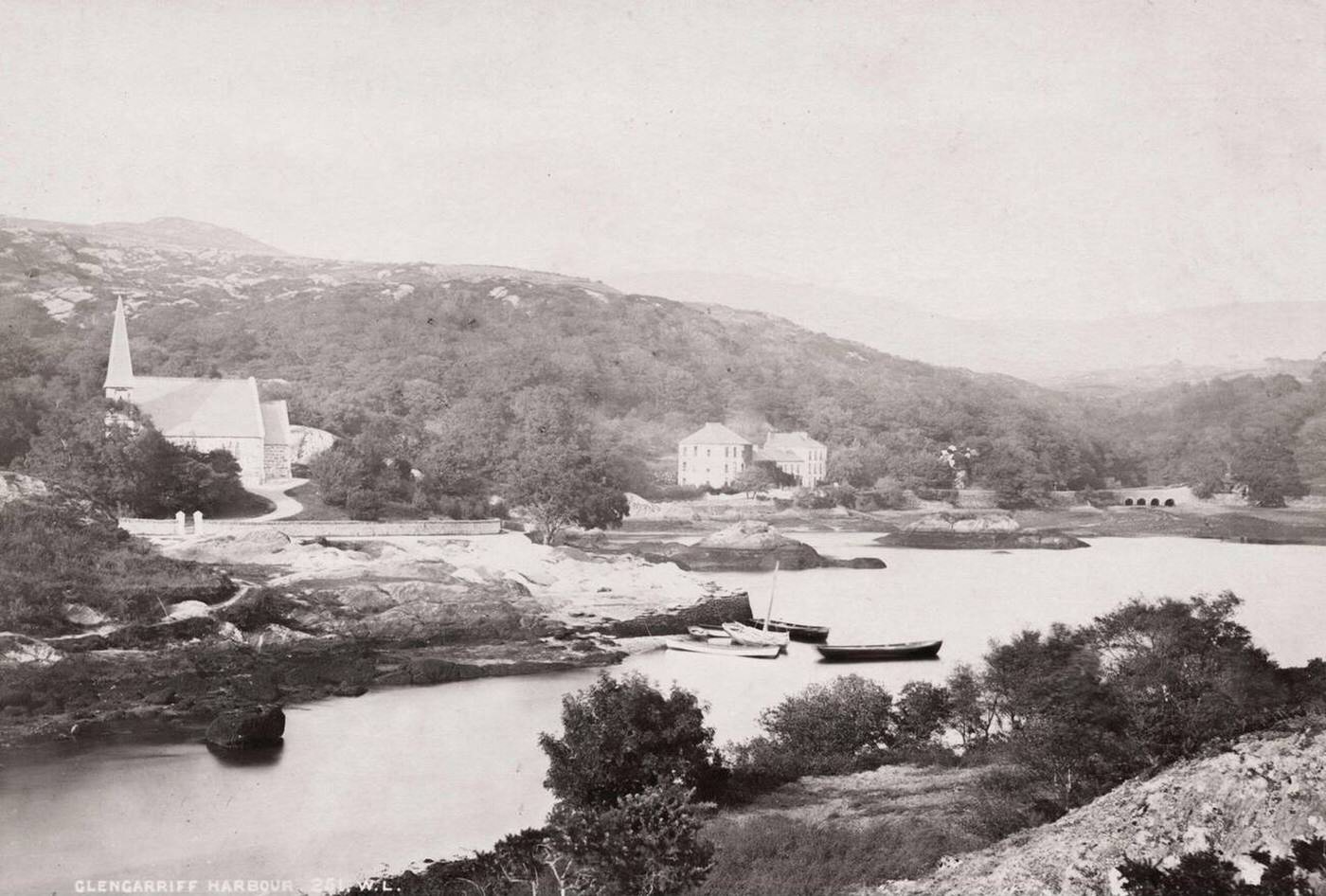

Life in the cities presented its own challenges. Dublin was a city of stark contrasts, with elegant Georgian architecture standing beside some of the most horrific tenement slums in all of Europe. Families lived packed into single, crumbling rooms with little sanitation or hope of escape. In the north, Belfast was a different world. It was an industrial powerhouse of the British Empire, booming with linen mills and giant shipyards that were building the most advanced ships in the world. This industrial divide between the nationalist, largely rural south and the unionist, industrial north was a deep fault line that would define Irish politics for the next century. Through it all, the Catholic Church remained the central pillar of community life for the majority, a source of spiritual guidance, education, and immense social authority. A young man on a farm in County Cork might spend his Sunday morning at Mass, his afternoon playing a fierce game of hurling, and his evening reading a nationalist newspaper detailing Parnell’s latest political victory, all while his sister packed her single suitcase for the long sea voyage to a new life in Boston.