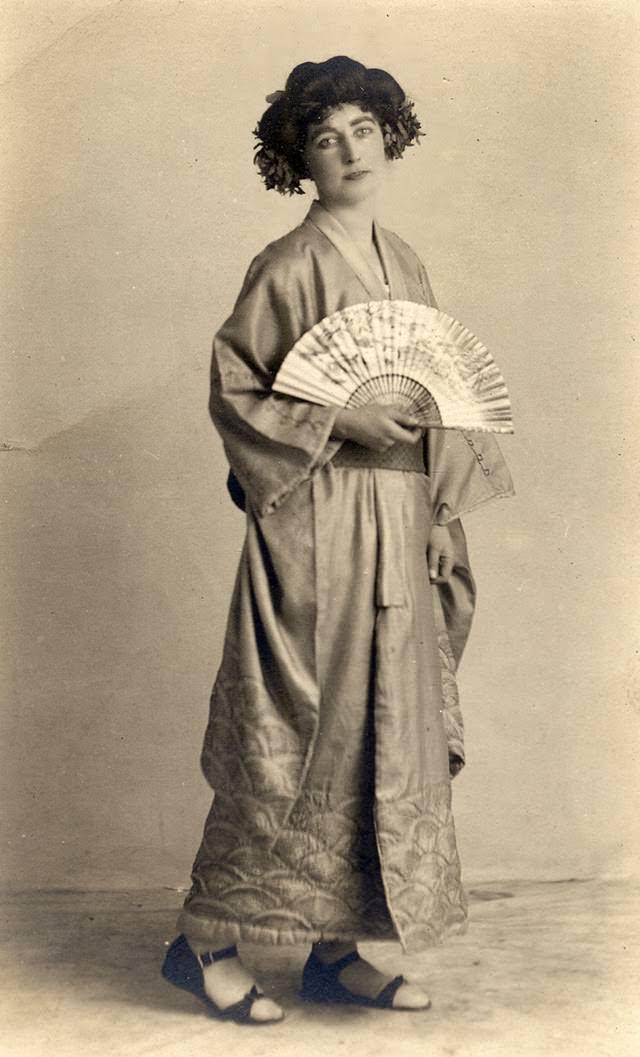

In the early 1900s, Japan opened its doors to an increasing number of Western tourists. For European and American women visiting cities like Yokohama and Kyoto, a portrait in local dress became a mandatory activity. They visited commercial photography studios specifically designed for foreign travelers. In these studios, women rented colorful silk kimonos to wear for a designated period. The resulting photograph served as proof of their exotic travels to the Far East. It was the ultimate souvenir to paste into a scrapbook or mail home as a postcard.

The Studio Wardrobe

The garments provided by these studios differed from the everyday wear of Japanese citizens. Photographers stocked highly decorative kimonos featuring large, dramatic embroidery of dragons, chrysanthemums, or cherry blossoms. These bold designs appealed to Western tastes more than the subtle patterns favored by Japanese women of the era. The silk was often heavy and stiff. Studio assistants helped the women put on the layers, as the T-shaped garment required specific folding and tying techniques that were foreign to Western dressers.

A Mix of Cultures

The final look often combined Eastern clothing with Western fashion standards. While the women wore the kimono, they rarely removed their own corsets or undergarments. This resulted in a rigid, hourglass silhouette that contrasted with the straight, tube-like shape intended for the kimono. Many women also kept their Western hairstyles, piling their hair high on their heads or wearing large, brimmed hats alongside the traditional robe. In full-length shots, leather boots or high heels frequently peeked out from the hemline instead of the traditional split-toed tabi socks and zori sandals.

Read more

Incorrect Details

Because the women did not understand the cultural rules of the garment, errors in styling were common in these portraits. A strict rule in Japan dictates that the collar must cross left over right. The reverse crossing, right over left, is reserved exclusively for dressing the deceased for funerals. Unaware of this custom, many foreign women crossed the collar right over left. Additionally, they often tied the obi, or sash, loosely or placed it too low on the waist. These mistakes are obvious to a knowledgeable observer but went unnoticed by the tourists who simply wanted a beautiful picture.

Props and Poses

To complete the fantasy, photographers handed their subjects specific accessories. Women held paper parasols, known as wagasa, or opened folding fans to cover part of their face. They posed against painted backdrops depicting idealized scenes of Mount Fuji, tea houses, or bamboo forests. Some women attempted to mimic the gestures of geisha, holding their hands in specific positions they had seen in woodblock prints. The studios usually hand-colored the black and white photographs later, adding vibrant reds, pinks, and greens to the fabric to make the image pop.