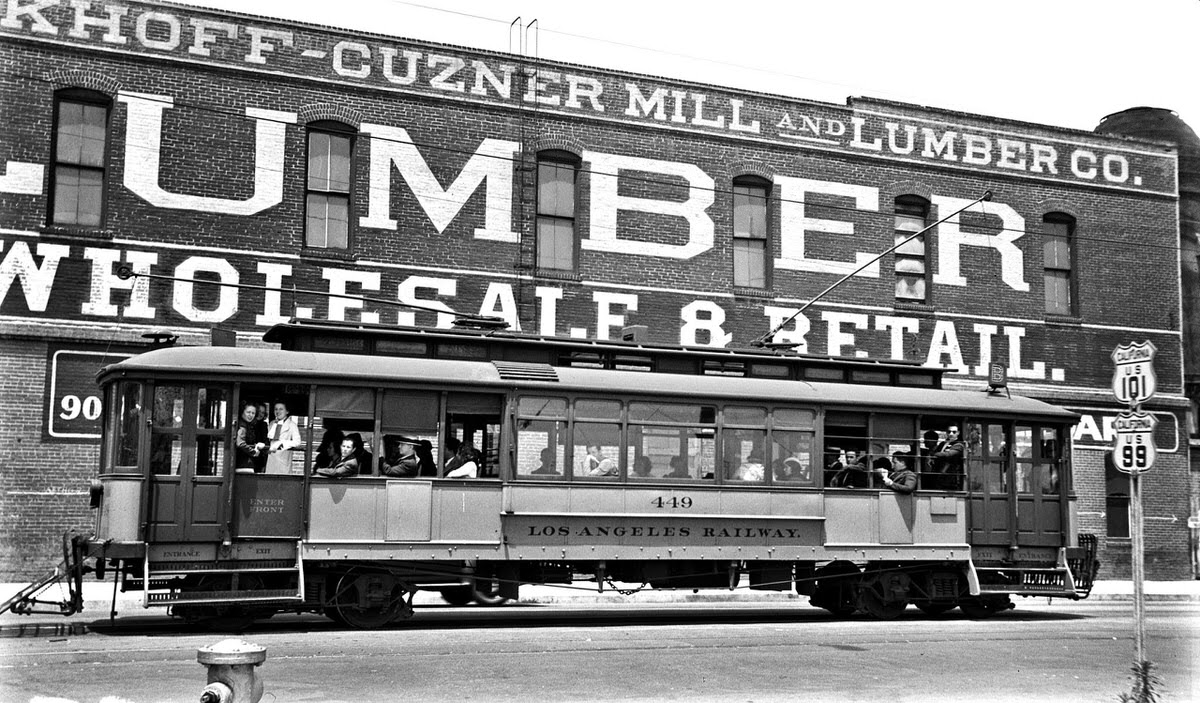

In the first decade of the 20th century, the Los Angeles Railway controlled local transit within the city center. Known to locals as the “Yellow Cars,” these vehicles differed from the faster “Red Cars” that traveled long distances to the suburbs. The Yellow Cars operated on narrow-gauge tracks, which were slightly thinner than standard railroad lines. They served the dense neighborhoods of downtown, Eco Park, and South Los Angeles. This system was the workhorse of the city, carrying millions of passengers annually on short, frequent trips.

Henry Huntington’s Investment

Henry Huntington, a wealthy railroad magnate, purchased the system in 1898 and immediately began a massive modernization project. He replaced the remaining horse-drawn carriages and cable cars with electric trolleys. Under his ownership, the railway expanded rapidly into undeveloped areas. Real estate developers built new neighborhoods along these tracks, knowing that reliable transportation would attract buyers. This strategy turned dusty fields into thriving districts like West Adams almost overnight.

Read more

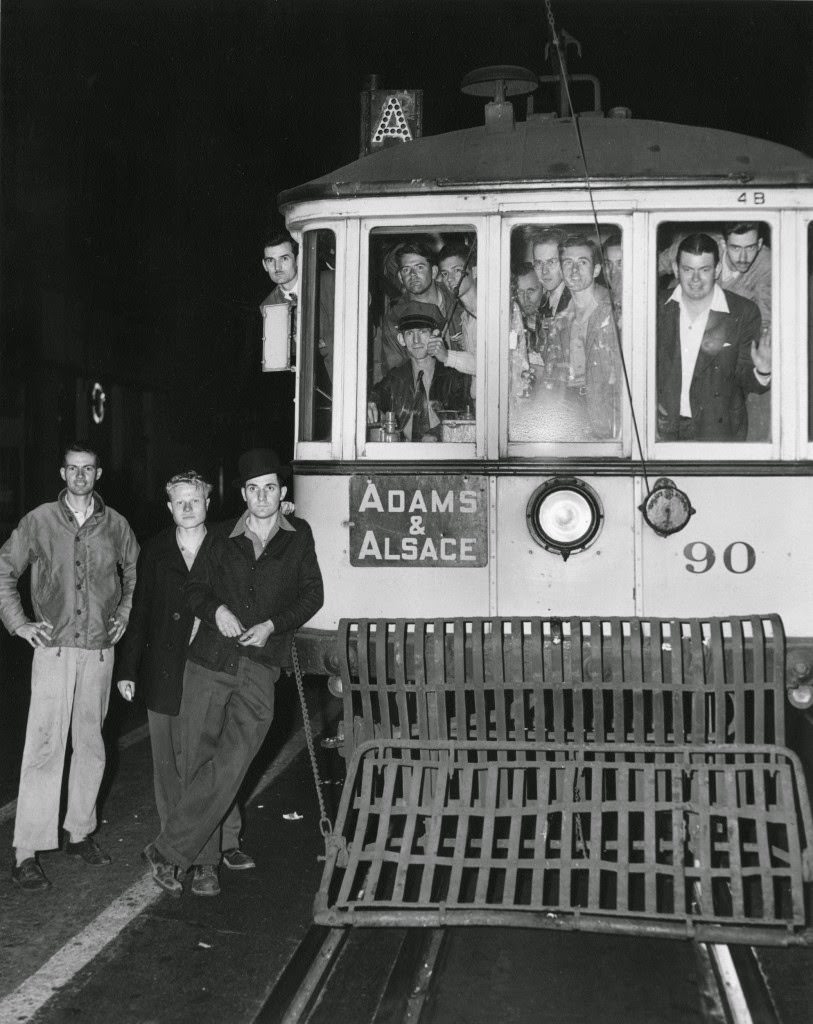

The “Sowbelly” Design

By 1902, the railway introduced a distinct vehicle technically called the Type B, but nicknamed the “Sowbelly.” Engineers designed this car with a unique, low-slung center section. The middle doors were close to the ground, allowing passengers to step inside easily without climbing steep stairs. This design sped up the boarding process significantly at busy stops. The Sowbelly cars became an icon of the era, recognizable by their curved sides and the conductor standing in the center well to collect fares.

The Five-Cent Fare

The Los Angeles Railway operated on a strict five-cent fare policy. A ride cost a single nickel regardless of how far a passenger traveled within the city limits. This low price made the streetcars accessible to everyone, from wealthy bankers to factory workers. Conductors carried heavy coin changers on their belts and rang a bell to register every payment. This fixed rate encouraged mobility, allowing workers to live in spacious residential areas while commuting cheaply to jobs in the industrial district.

Powering the Grid

A complex web of overhead copper wires powered the fleet. Each streetcar had a trolley pole extending from its roof to the wire to draw electricity. The motorman stood at the front of the car, controlling the speed with a heavy brass handle. He used his foot to stomp on a floor pedal, ringing a loud gong to warn pedestrians and wagons to clear the track. At night, blue sparks often showered down from the wires as the metal wheels crossed through intersections.

Congestion on Broadway

As the decade progressed, the streetcars faced intense traffic on major thoroughfares like Broadway and Main Street. They shared the road with horse-drawn delivery wagons, bicycles, and early automobiles. Since the tracks ran down the middle of the street, the trolleys frequently got stuck behind slow-moving vehicles. To keep the schedule moving, the railway ran cars at intervals as short as 90 seconds during rush hour. This created a solid wall of yellow steel moving through the heart of the city.