In 1955, MGM released It’s Always Fair Weather, a musical satire that brought together two distinct forces of screen charisma—Dolores Gray and Cyd Charisse. While Gene Kelly, Dan Dailey, and Michael Kidd carried much of the male-driven story, Gray and Charisse injected the film with glamour, technical precision, and sharply defined character work.

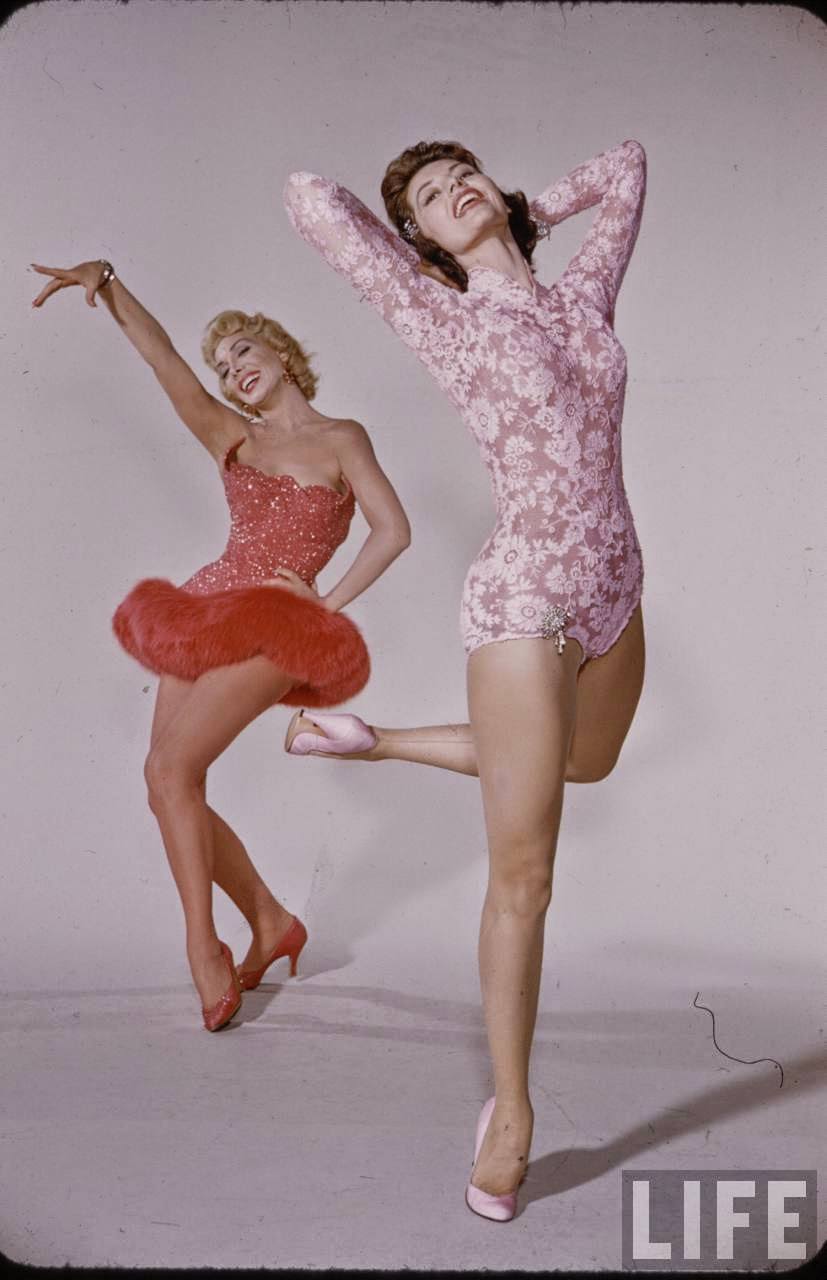

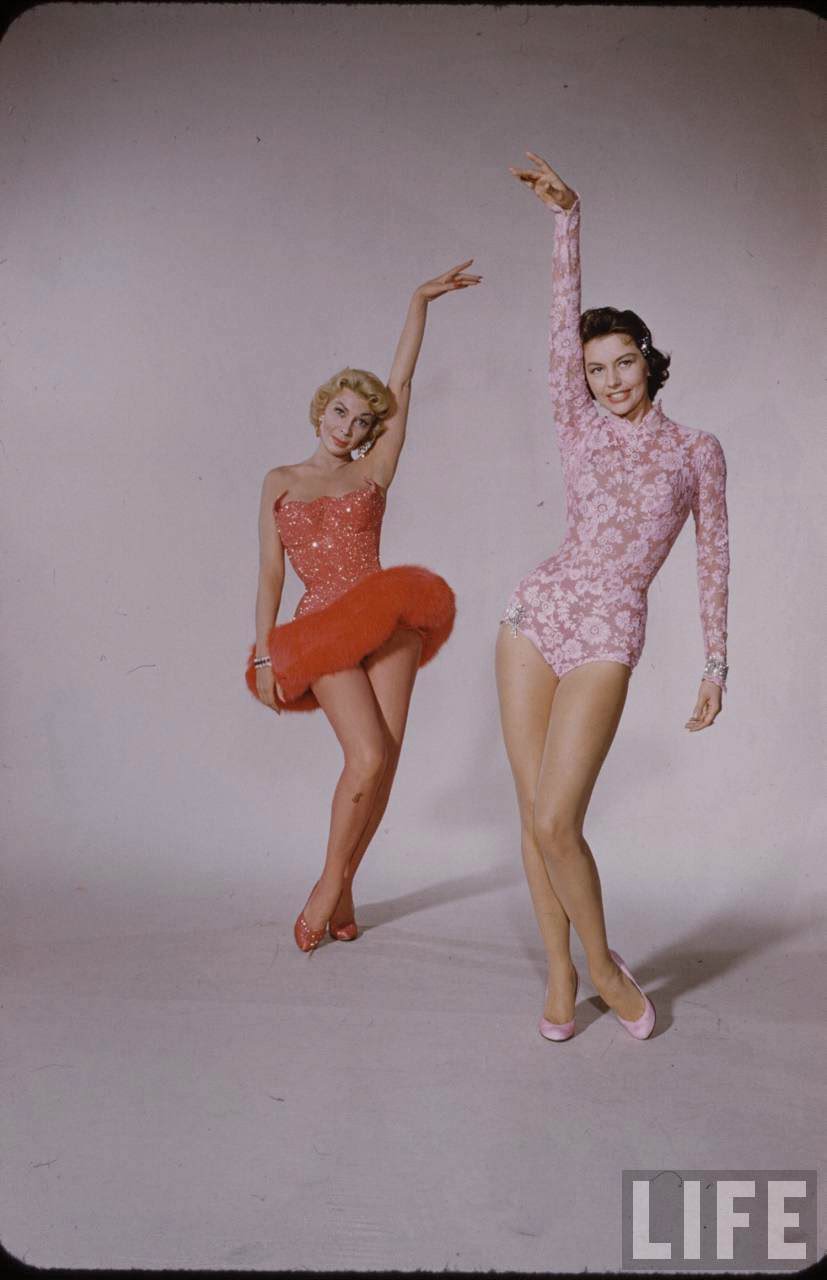

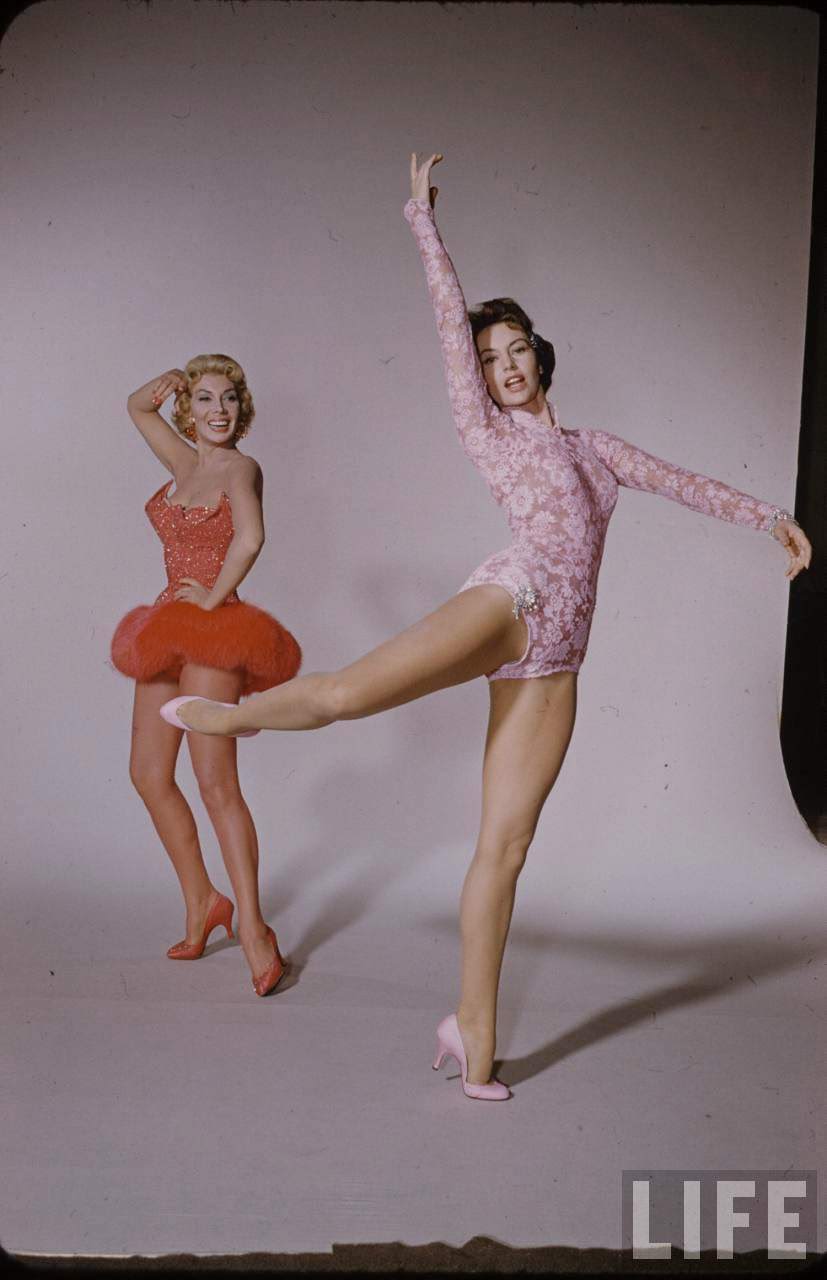

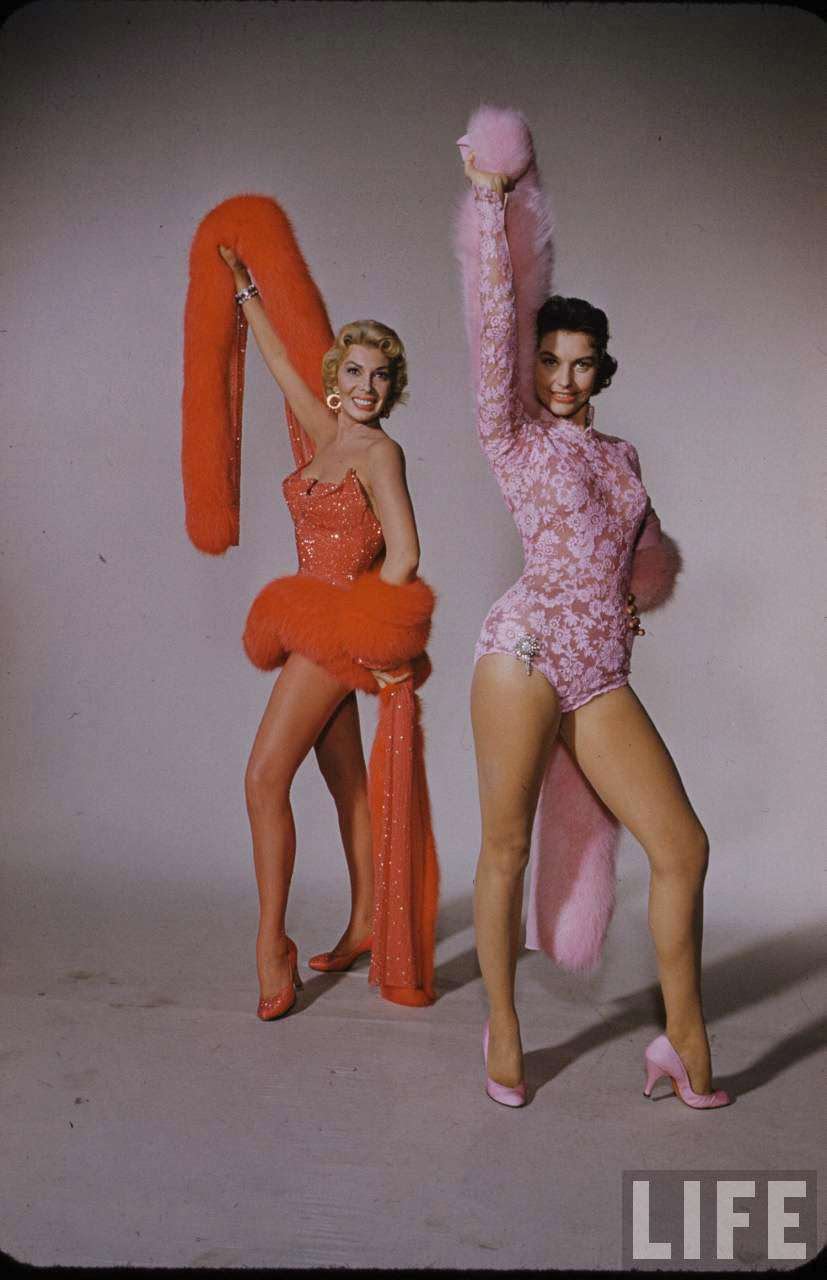

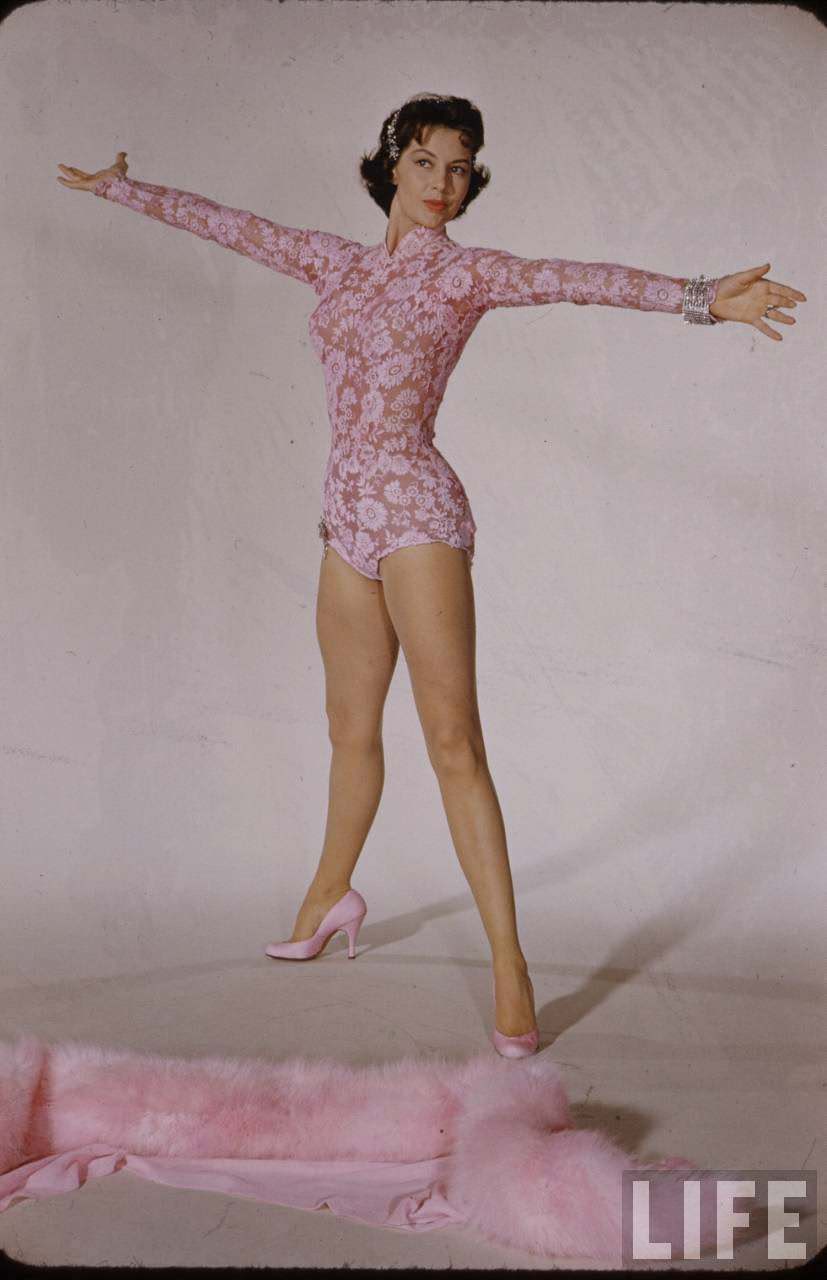

Cyd Charisse appeared as Jackie Leighton, a poised and polished television producer with a professional exterior and a grounded moral compass. Her performance carried the kind of cool control that contrasted against the rough edges of the three male leads. In her dance sequences, her trademark leg extensions and precise footwork were paired with the wide CinemaScope frame, allowing every movement to unfold in full view. The choreography emphasized her elegance—long glides, smooth turns, and controlled lines that never felt rushed. Costuming matched her style: tailored suits and sleek dresses in jewel tones that stood out against the bright Eastmancolor palette.

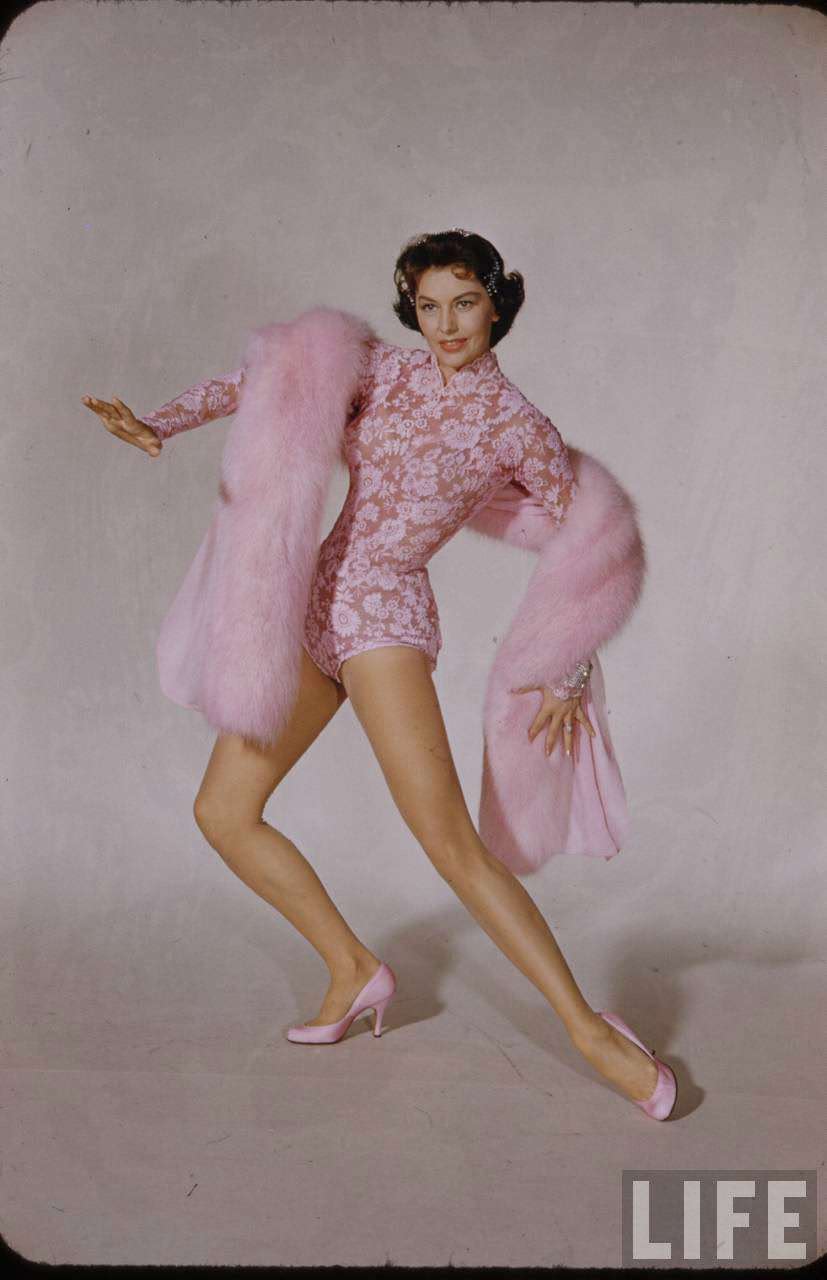

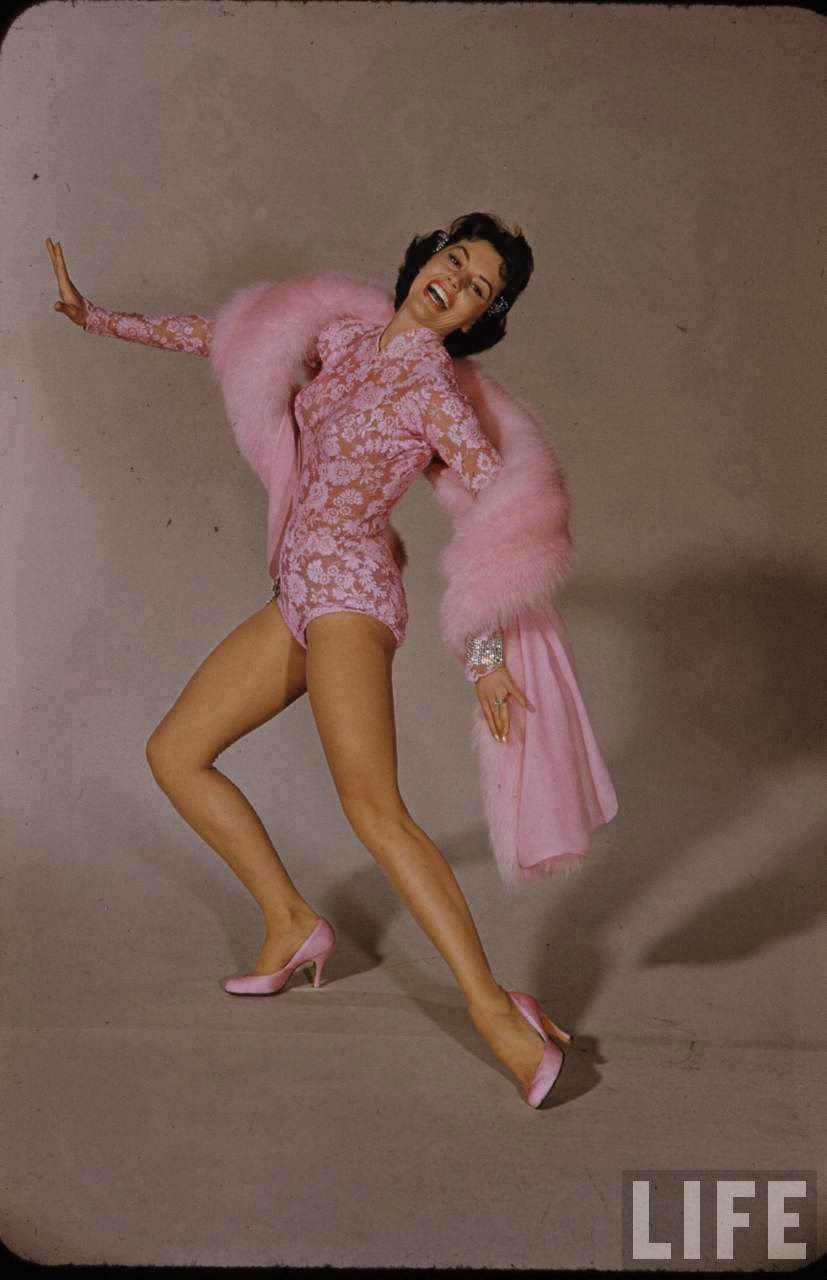

Dolores Gray played Madeline Bradville, a flamboyant television hostess with a taste for the absurd and a wardrobe designed to dominate every frame. Her costumes leaned into theatrical excess—feathered hats, sparkling gowns, and bold shapes that matched her vocal power. Gray’s delivery was crisp and controlled, with every syllable landing like a cue in a live broadcast. Her big number, “Thanks a Lot, But No Thanks,” was staged as a satirical fantasy, mixing tightly timed choreography with a wry take on romantic pursuit.

Read more

The contrast between the two women was deliberate. Charisse brought sleek sophistication, measured gestures, and understated authority. Gray projected oversized personality, sweeping gestures, and comic bite. In scenes together, they occupied opposite ends of the visual and emotional spectrum, yet both commanded the audience’s attention.

Cinematography took full advantage of CinemaScope, framing Charisse in long, fluid tracking shots and giving Gray grand, front-facing moments that filled the frame. Eastmancolor saturated their costumes, making reds deeper, blues brighter, and gold accents shimmer under the studio lights. Every shot reinforced the different energies they brought to the story.

Their roles also reflected the film’s satirical edge. Charisse’s character underscored the behind-the-scenes control of television production, while Gray’s performance lampooned the superficial, high-gloss entertainment side of the medium. Each worked within the film’s cynical tone while still delivering the kind of musical spectacle audiences expected from MGM.