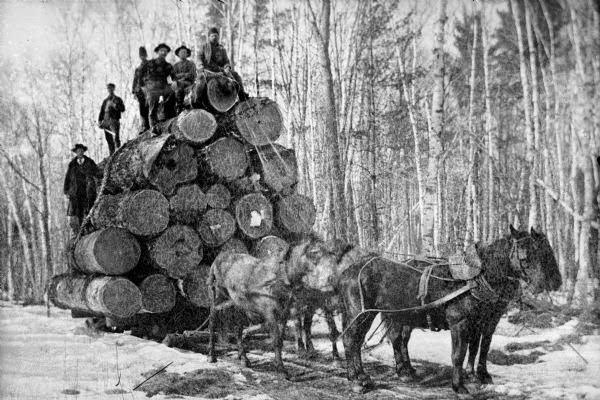

In the early 1900s, the draft horse was the backbone of American labor. These massive animals, often weighing over a ton, were bred for strength and endurance, capable of pulling loads that machines of the time could not yet handle.

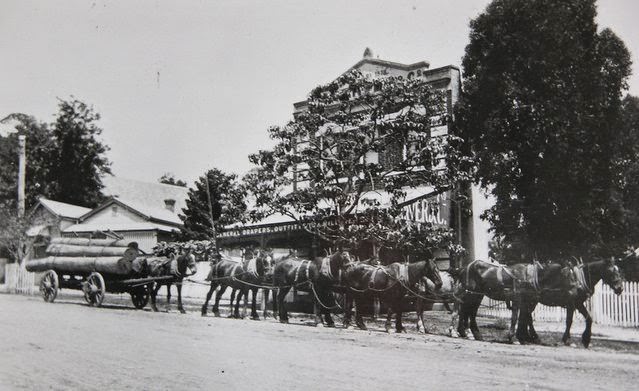

They hauled wagons stacked with timber, coal, or grain through city streets and along rural dirt roads. On farms, they pulled plows, harrows, and seed drills, breaking heavy soil and preparing acres of land for planting. Their power allowed farmers to cultivate more ground in a day than smaller teams or human labor could manage.

Breeds such as the Percheron, Belgian, Shire, and Clydesdale dominated the workhorse scene. Each had its strengths: Belgians were known for sheer pulling power, while Percherons combined muscle with agility, making them ideal for both fieldwork and transportation in tighter spaces. Shires and Clydesdales often worked in cities, where their height and steady temperament made them favorites for hauling goods through busy streets.

Read more

Draft horses required careful handling. Their size demanded skilled teamsters who understood harnessing, pacing, and rest schedules to prevent strain. Feeding a team was a significant daily task—oats, hay, and fresh water were essential to keep them strong for long hours of labor.

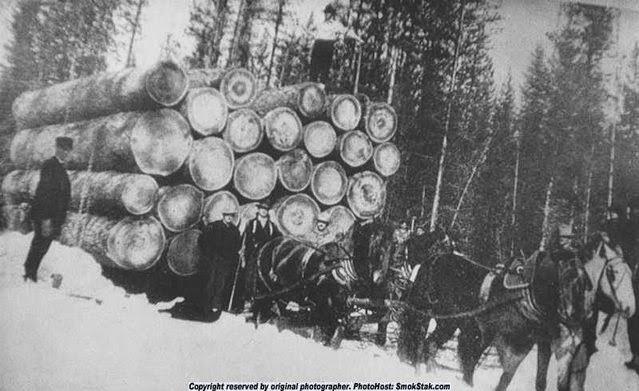

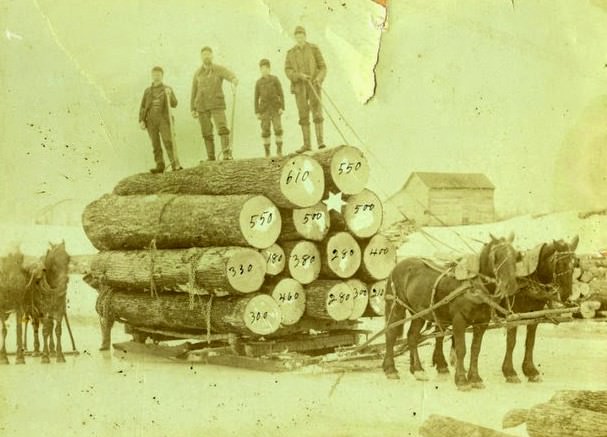

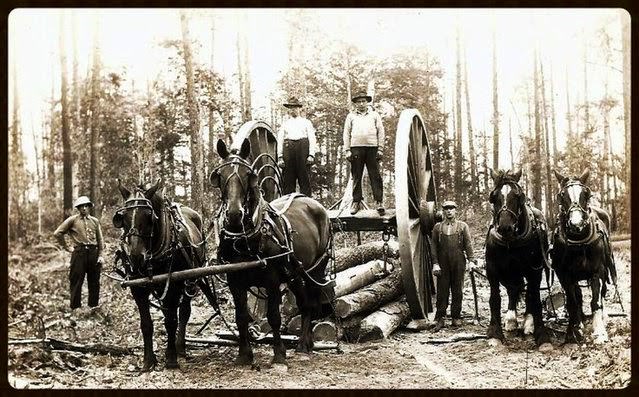

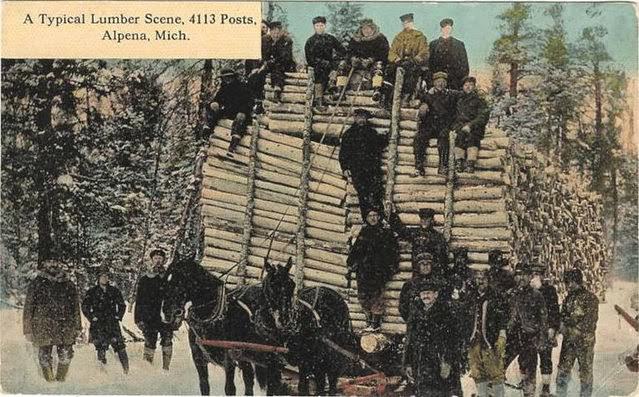

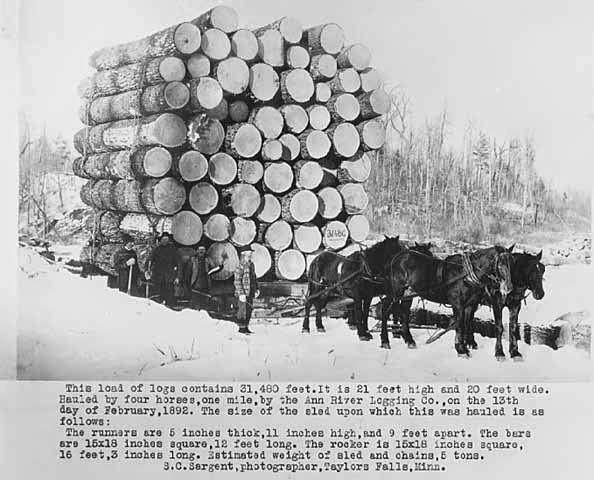

In logging camps, horses dragged massive logs from forests to riverbanks or rail lines. Their sure-footedness allowed them to navigate muddy, uneven terrain that early trucks could not manage. In winter, they pulled sleighs loaded with supplies or firewood across frozen ground.

In cities, draft horses were harnessed to brewery wagons, delivery carts, and street-cleaning equipment. Their steady pace and reliability made them indispensable in an era before widespread motorized transport. Even after trucks began replacing them, many businesses kept teams for specific jobs, trusting their strength over early mechanical engines.