The 1940s was a defining time for American railroads and the powerful machines that ran on their tracks. Locomotives were the backbone of transportation across the vast distances of the United States. During this decade, two main types of power ruled the rails: steam and, increasingly, diesel.

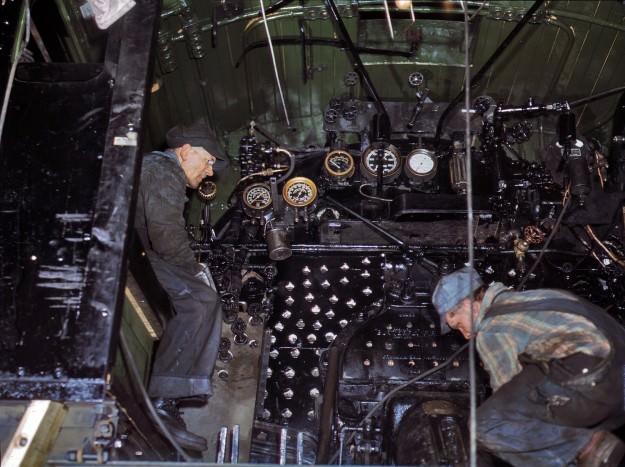

Steam locomotives were still the most common sight on American tracks throughout the early and mid-1940s. These were large, imposing machines built of steel, iron, and brass. They burned fuel, usually coal or oil, in a firebox to heat water in a large boiler. This created high-pressure steam. That steam was directed into cylinders, pushing pistons back and forth. These pistons were connected to the large driving wheels by rods, turning the wheels and making the train move forward.

Steam engines were known for their dramatic appearance and sounds. Thick black or gray smoke often poured from their tall smokestacks. White steam hissed from various pipes and valves, especially when the engine was stopped or starting. The sound of a steam locomotive was distinctive – a deep whistle that could be heard for miles, and the rhythmic “chuffing” sound as the engine worked hard to pull its load, getting faster as the train picked up speed.

Read more

These steam locomotives came in many different sizes and designs, built by companies like Baldwin, Alco, and Lima. Railroads ordered specific types depending on the job. Some were huge, heavy freight locomotives built for raw power to haul mile-long trains loaded with coal, ore, lumber, or manufactured goods over mountains and across the plains. These engines had many large driving wheels to grip the track and pull immense weight. Other steam engines were designed for speed and pulling passenger trains. These often had fewer driving wheels but were built to travel quickly and smoothly between cities. Locomotives designed for switching cars in busy rail yards were smaller and built for maneuverability.

The 1940s saw the United States deeply involved in World War II. This placed an enormous demand on the railroad system. Locomotives and trains were absolutely critical to the war effort. They transported millions of troops across the country to training camps and ports. They moved massive amounts of military equipment – tanks, jeeps, artillery, ammunition – from factories to where they were needed. Raw materials like coal, steel, and oil, essential for wartime production, were carried by freight trains in huge quantities. The railroads and their locomotives worked around the clock, facing heavy wear and tear but proving their vital importance to the nation.

Passenger trains were also a major way for people to travel long distances in the 1940s, especially during the war when gasoline was rationed and air travel was not yet common. Long-distance passenger trains offered different classes of service, including coach seats, Pullman sleeping cars for overnight journeys, and dining cars where passengers could eat meals. These trains were often pulled by the most powerful and fastest passenger steam locomotives a railroad owned. Traveling by train was an experience, with the sounds of the rails and the scenery passing by.

While steam was still king, the 1940s was the decade when a new type of power began its rise: the diesel locomotive. Early diesel engines had been around for a while, mostly for switching work, but in the 1940s, more powerful diesel-electric locomotives started appearing on main lines, first for passenger trains and then for freight. These locomotives looked very different from steam engines. They were often boxy or had a more streamlined, sleeker shape. They didn’t produce clouds of steam or smoke in the same way.

Diesel-electric locomotives used a large diesel engine to turn a generator, creating electricity. This electricity then powered electric motors connected to the axles, which turned the wheels. This system was different from the direct push-and-pull of the steam piston. Diesels offered advantages that railroads began to notice in the 1940s. They could run for much longer distances without needing to stop for fuel and water as frequently as steam engines. They often required less maintenance and could be operated by a single engineer without a fireman constantly tending the fire.

In the 1940s, you would see both types of locomotives working side-by-side. A large steam engine might be pulling a heavy freight train over a mountain pass, while a new, shiny diesel locomotive pulled a fast passenger train on a different route. Or a small diesel switcher worked busily arranging cars in a large rail yard. The railroads were operating a mix of the old, proven steam technology and the new diesel power that represented the future.