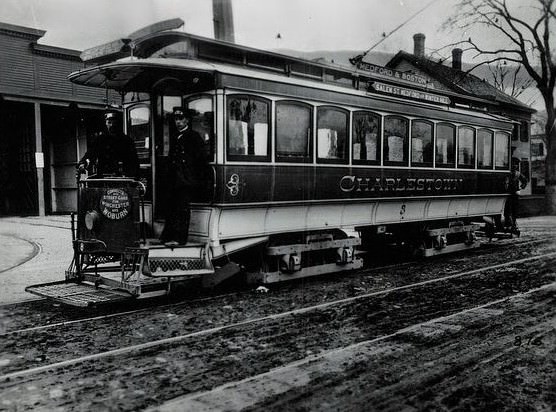

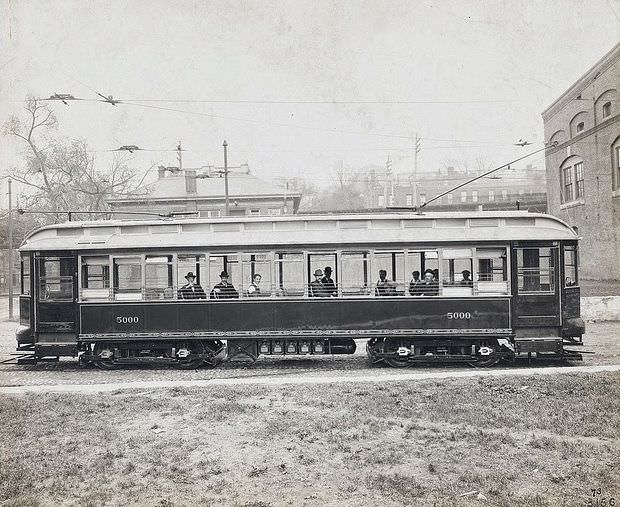

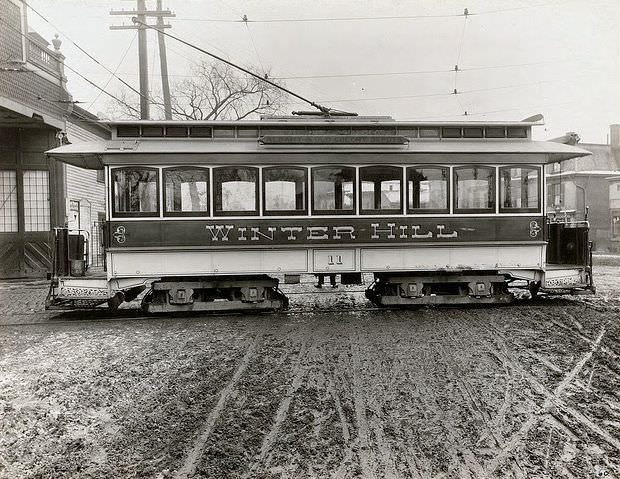

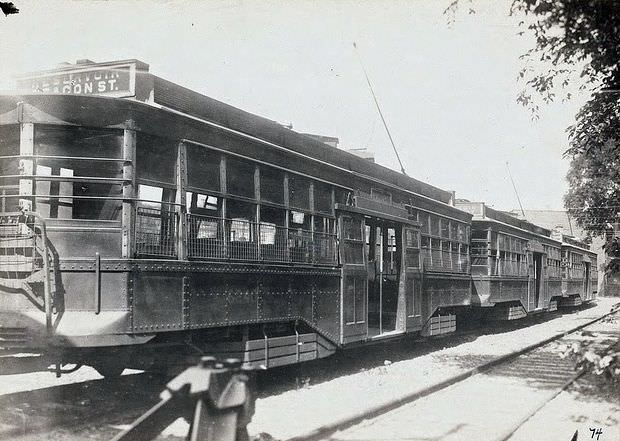

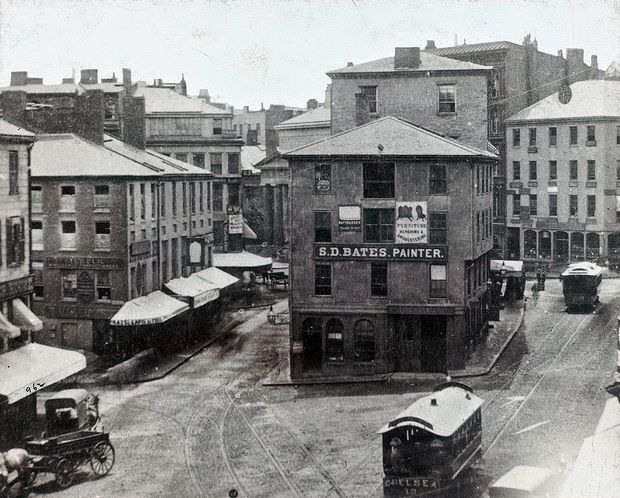

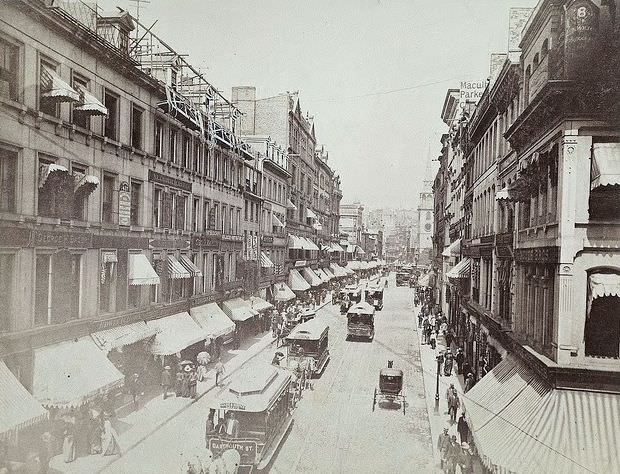

By the early 1900s, electricity had completely replaced horse power on Boston’s transit lines. The West End Street Railway operated a vast fleet of electric trolleys that navigated the city’s notoriously narrow and winding streets. A web of copper wires hung over the roads, supplying power to the cars through trolley poles. These vehicles connected the dense residential neighborhoods to the business distinct. While faster than horses, these surface cars frequently faced gridlock in the downtown area where the streets were thinnest.

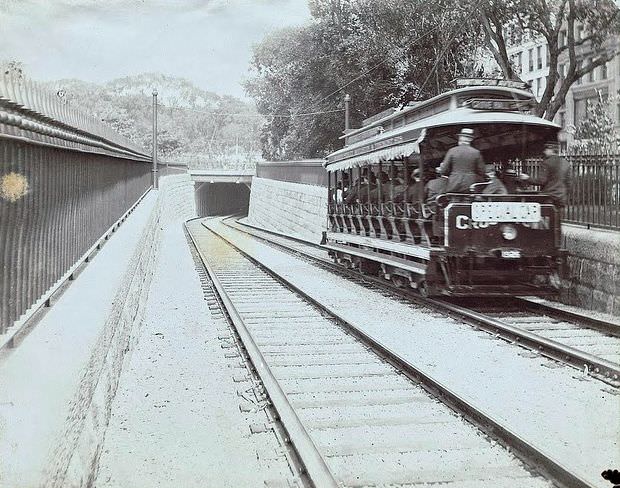

The Tremont Street Subway

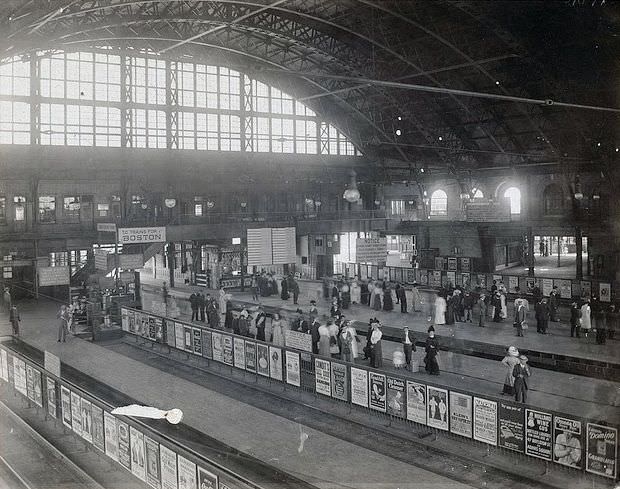

To solve the downtown congestion, Boston engineers buried the trolley lines. The Tremont Street Subway, which had opened just before the turn of the century, served as a critical funnel for the streetcar network in the early 1900s. Surface cars from the suburbs descended into tunnels at the Public Garden and near North Station.

Once underground, the trolleys moved without obstruction from wagons or pedestrians. Stations like Park Street and Boylston featured wide stone platforms where thousands of passengers boarded daily. This subway tunnel allowed the transit company to remove tracks from the surface of Tremont Street, effectively unclogging the heart of the city.

Read more

The Rise of the Elevated

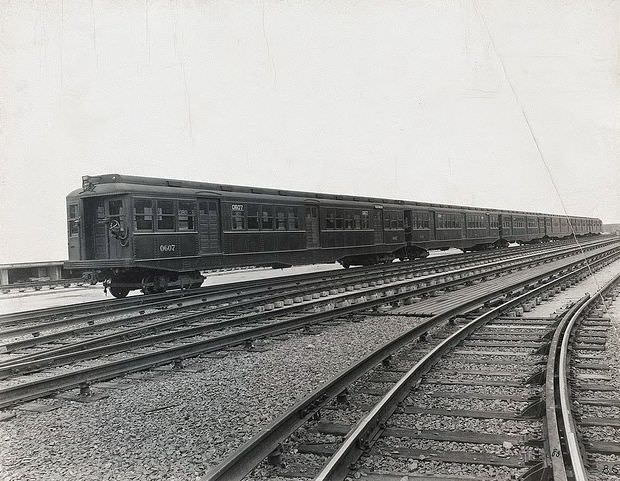

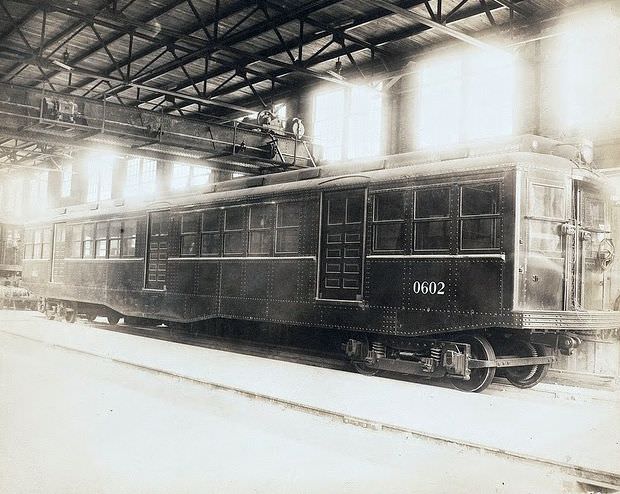

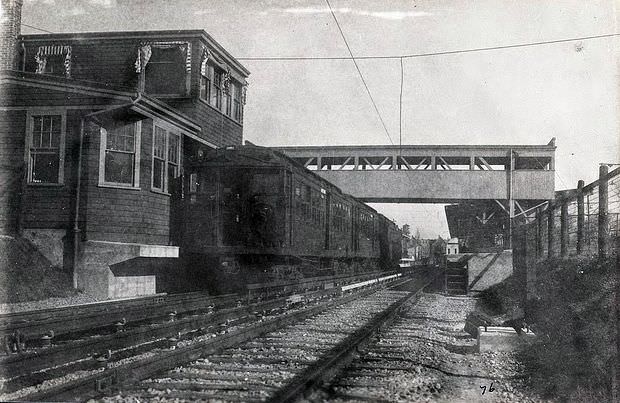

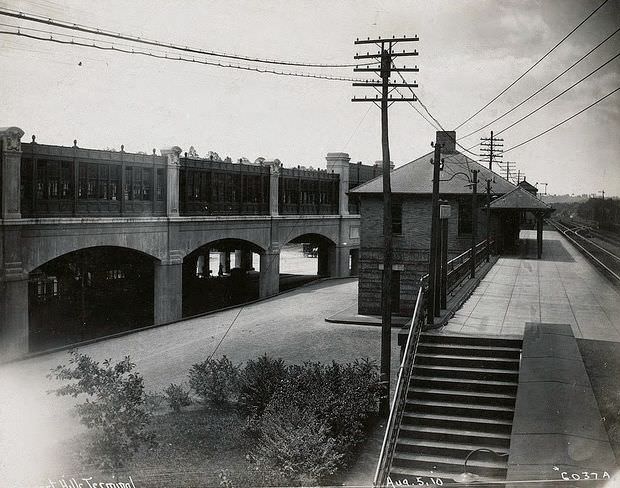

While trolleys ran underground, heavy rail trains took to the sky. The Boston Elevated Railway Company, often called BERy, opened the Main Line Elevated in 1901. Massive steel trestles dominated the skyline above avenues in Charlestown, the South End, and Roxbury. The “El” trains ran from a northern terminal at Sullivan Square to a southern terminal at Dudley Square.

These trains bypassed street-level traffic entirely, offering high-speed travel across the metropolis. The Atlantic Avenue Loop specifically served the waterfront, connecting North Station and South Station. It carried commuters past the busy wharves and ferry terminals, though the sharp curves of the track forced the trains to screech and slow down as they navigated the harbor front.

A Unified Five-Cent Fare

The true innovation of the Boston system was the integration of these different modes of travel. BERy managed the surface trolleys, the subway, and the elevated trains as a single cohesive unit. A passenger paid a uniform five-cent fare to enter the system. This nickel fare included free transfers between the streetcars and the rapid transit lines.

At major interchanges like Dudley Square, the architecture facilitated this movement. Elevated trains arrived on the upper level, while surface trolleys pulled into loops on the lower level. Commuters walked down ramps to switch vehicles without paying extra. This efficient transfer system encouraged the population to spread out, allowing workers to live in spacious suburbs like Dorchester while maintaining easy access to downtown jobs.