Plans for a bridge over the Firth of Forth started in the early 1800s. Early ideas focused on a tunnel or chain bridge. In 1873, Parliament approved a suspension bridge designed by Thomas Bouch. Work began in 1878 but stopped after the Tay Bridge collapsed in 1879. That disaster killed 75 people and ruined trust in Bouch’s designs. Engineers scrapped his Forth plan in 1881. Four railway companies formed the Forth Bridge Railway Company. They invited new designs to meet strict safety rules from the Board of Trade. The rules demanded the bridge handle wind loads of 56 pounds per square foot.

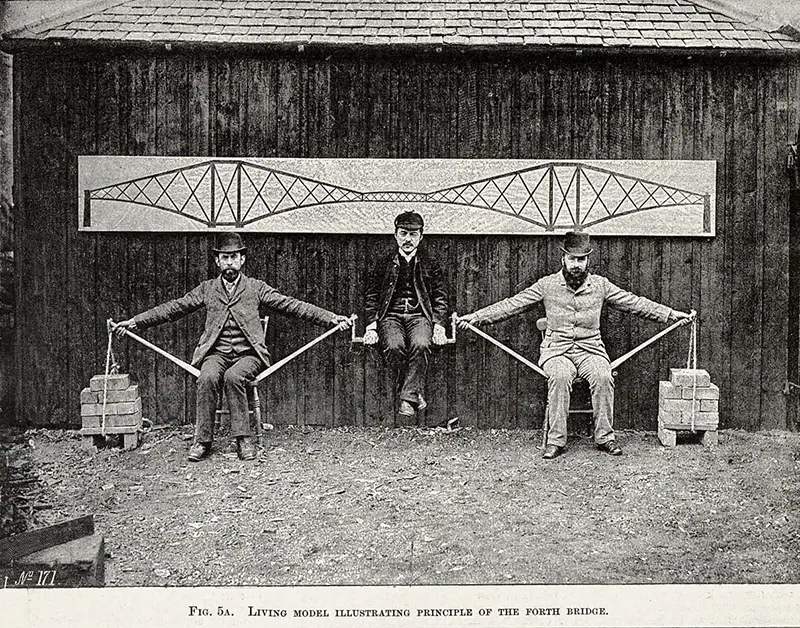

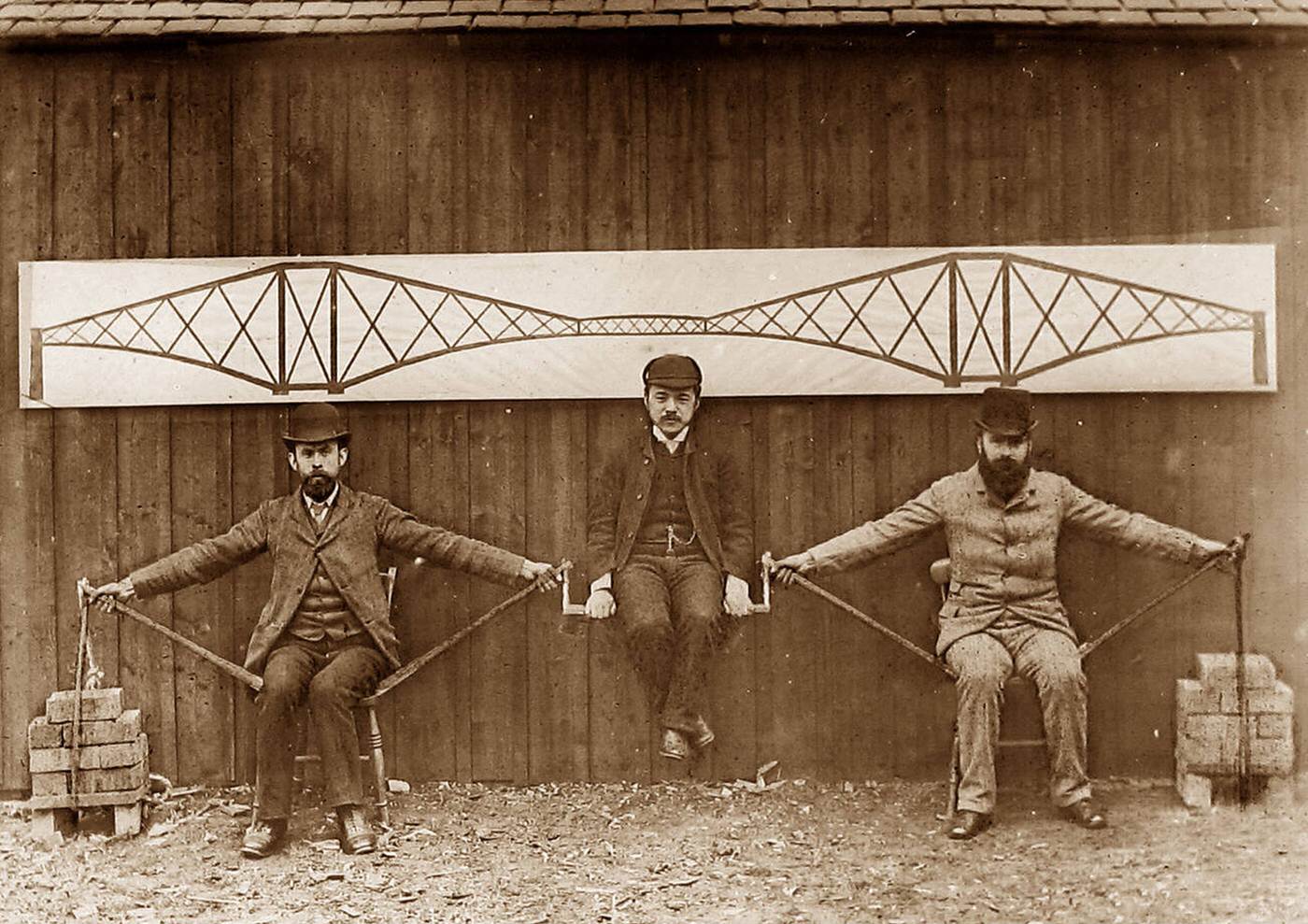

Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker created the winning cantilever design. Their plan used three double cantilevers connected by girders. Each main span measured 1,700 feet, the longest at the time. The total length reached 8,094 feet, including approach viaducts. The rail level sat 150 feet above high water for ships to pass. The design drew from ancient cantilever ideas but scaled them up with modern steel. Baker demonstrated the principle in 1887 with a photo of men forming a human cantilever. Kaichi Watanabe sat in the middle, held by arms from Fowler and Baker. This image used chairs and sticks to show balance and strength.

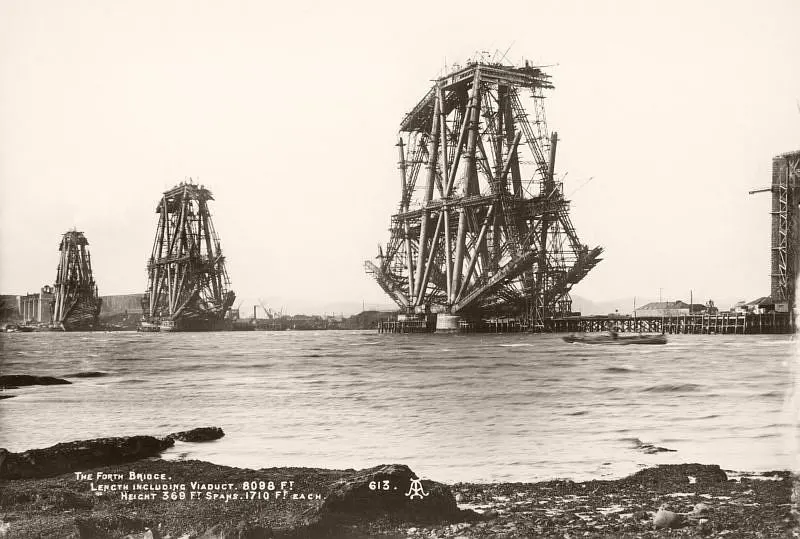

Construction contracts went to Sir William Arrol & Co. in December 1882. Site work started right away at South Queensferry and North Queensferry. Teams expanded old offices from Bouch’s project. They surveyed the riverbed and built jetties for materials. A steamer carried workers across the firth. By 1883, steel fabrication shops opened on site. Foundations began in February 1883 with granite piers on caissons.

Read more

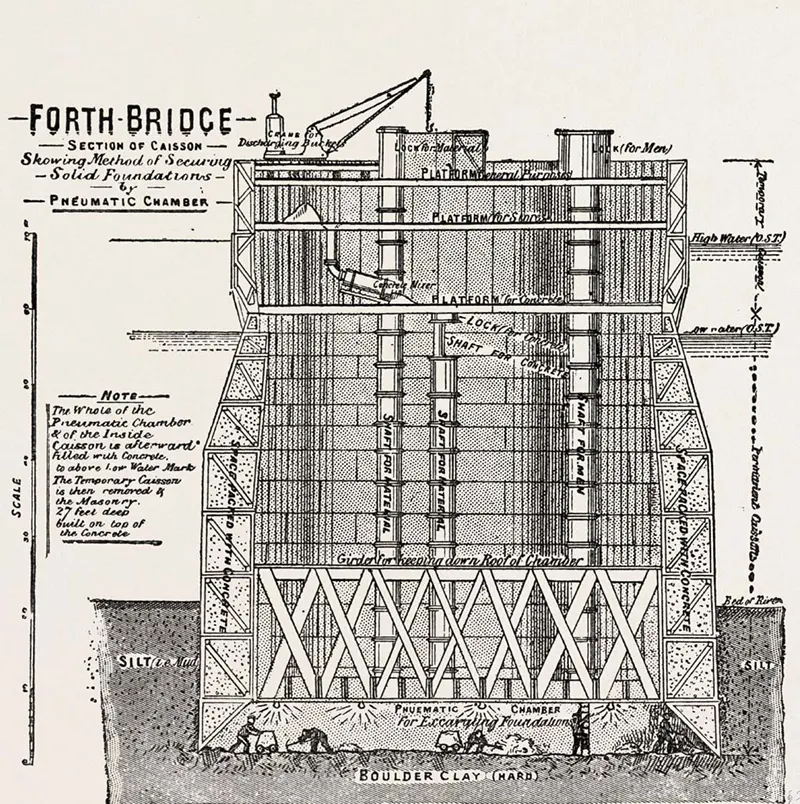

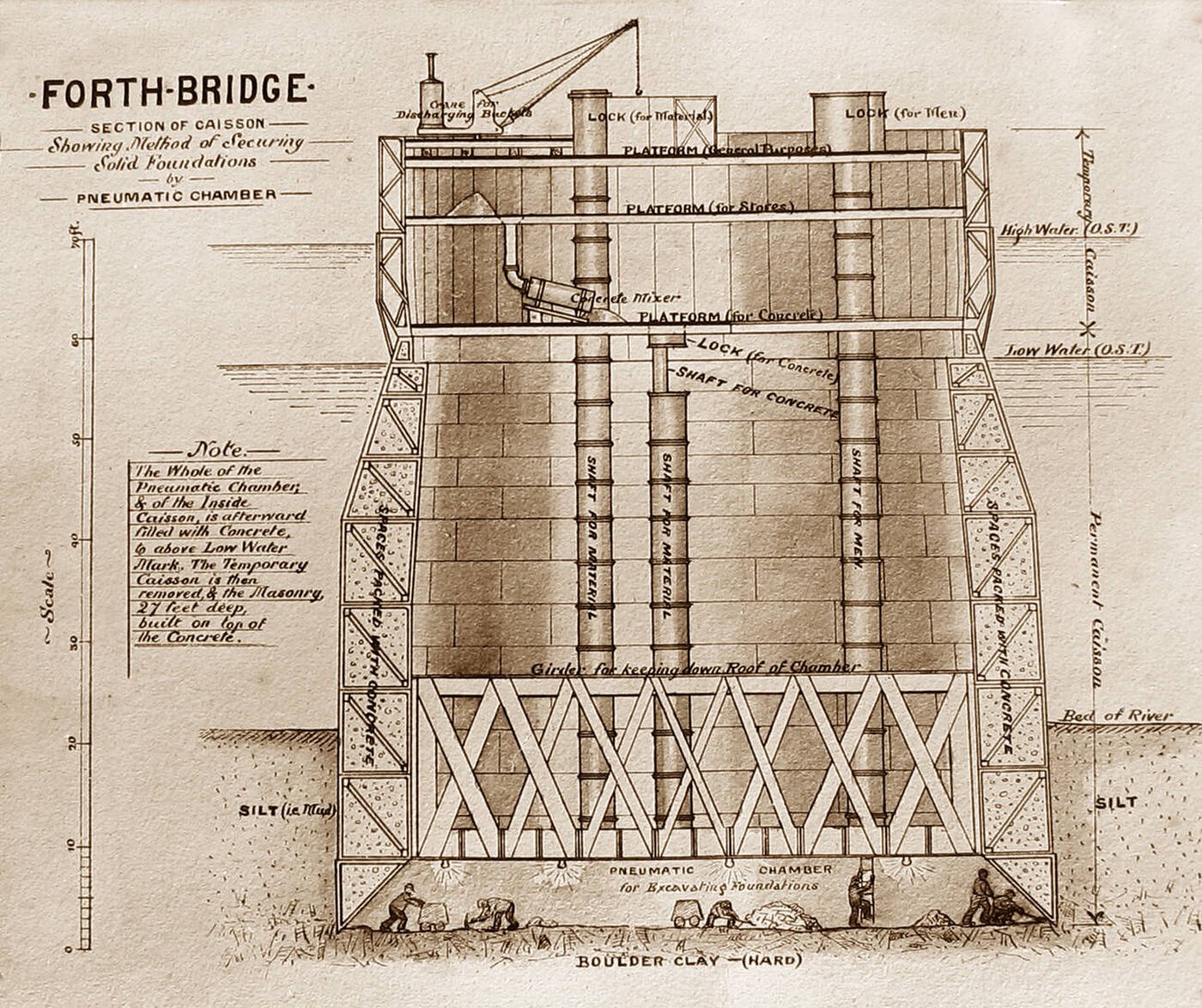

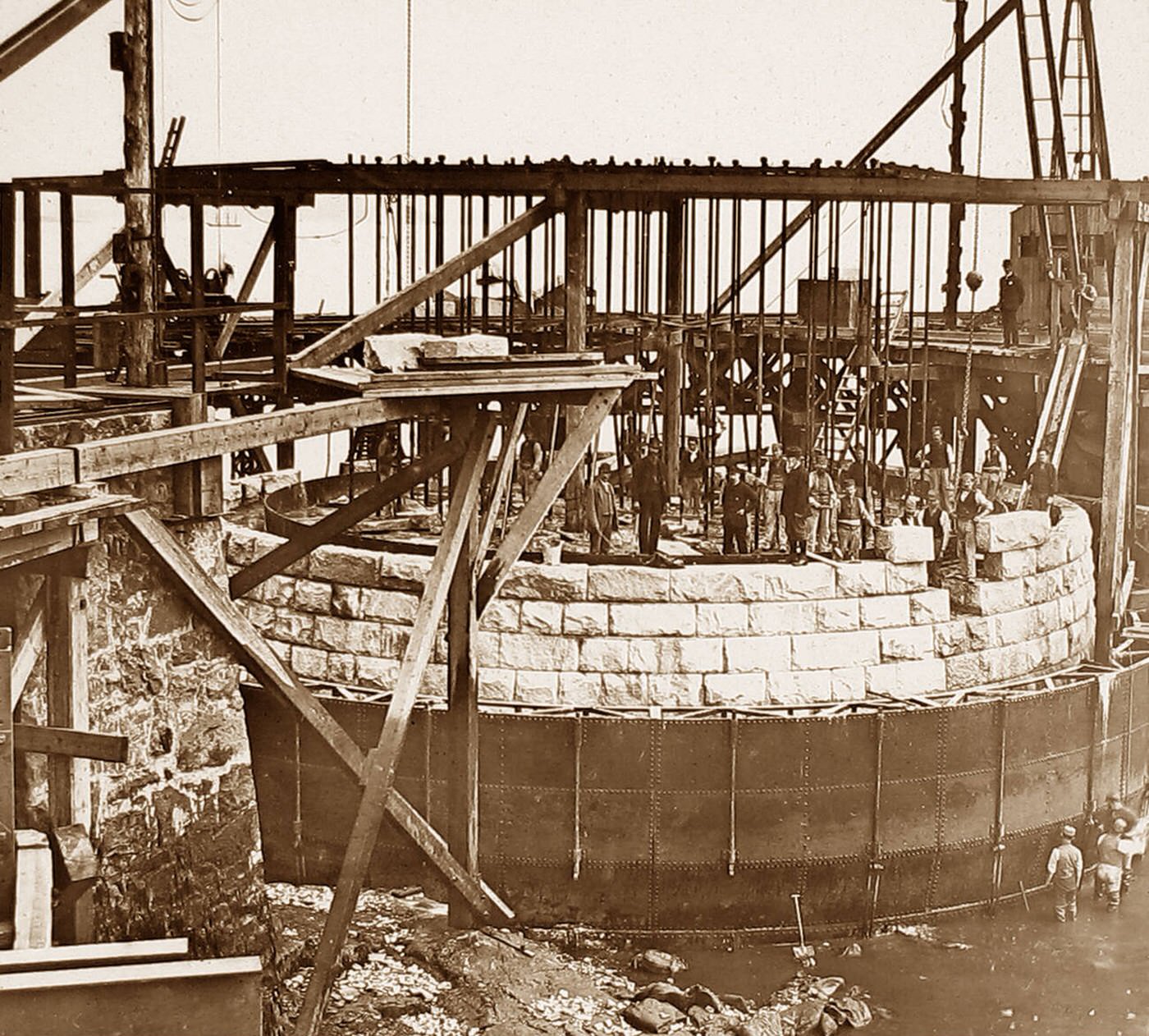

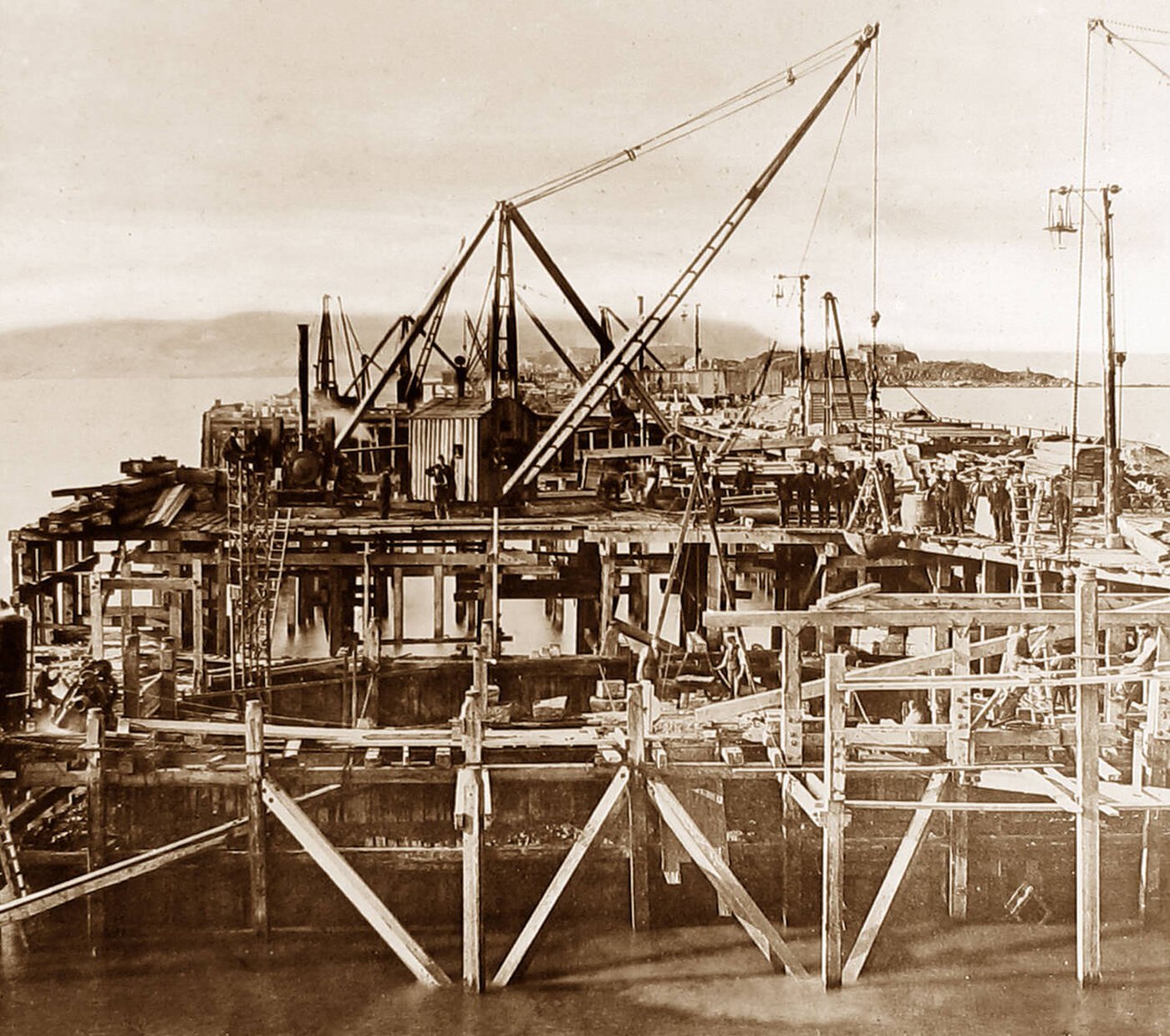

Caissons formed the base for the piers. These large wrought iron cylinders sank into the seabed. Workers pumped out water and used compressed air in deeper ones. Airlocks let men enter and exit safely. Six caissons launched from Glasgow between May 1884 and May 1885. The Inchgarvie south caisson tilted during a low tide on New Year’s Day 1885. Crews fixed it with timber braces and refloated it in October 1885. Foundations finished by 1886 after digging through silt and rock.

Piers rose from granite blocks on the caissons. Each pier supported a cantilever tower. Workers laid 640,000 cubic feet of granite and 140,000 cubic yards of masonry. Portland cement came from the Medway and stored on a barge. Approach viaducts built at lower levels and lifted with hydraulic rams every four days by 3 feet 6 inches.

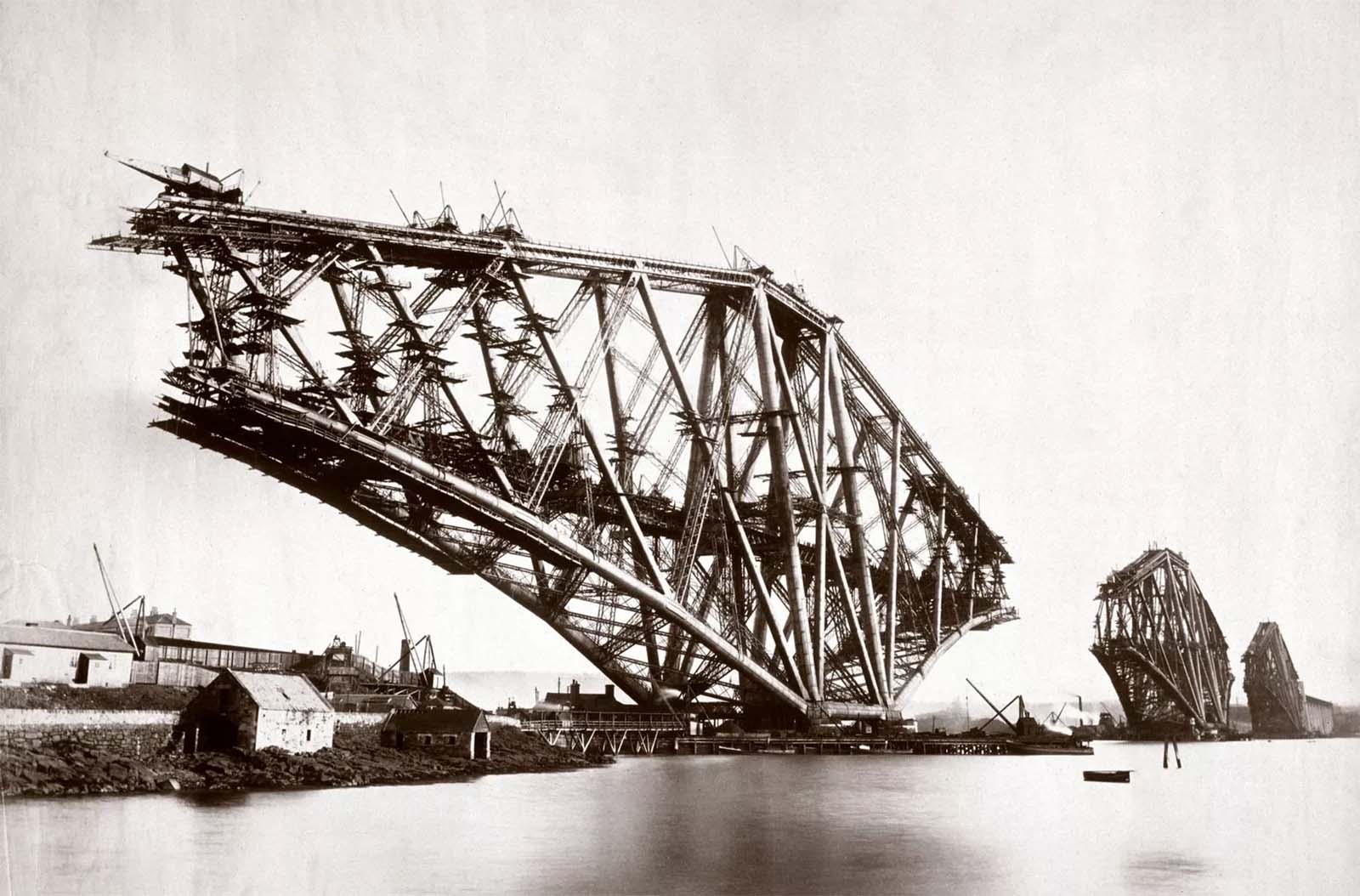

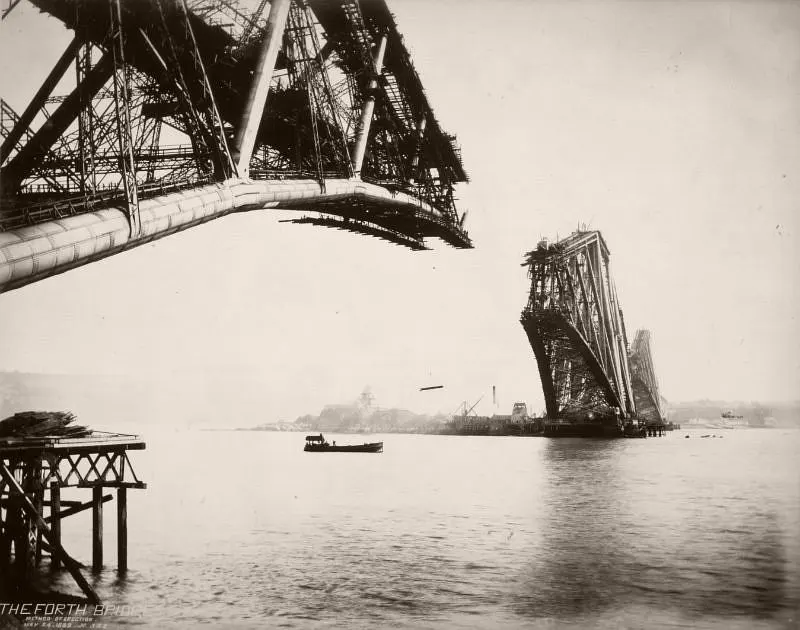

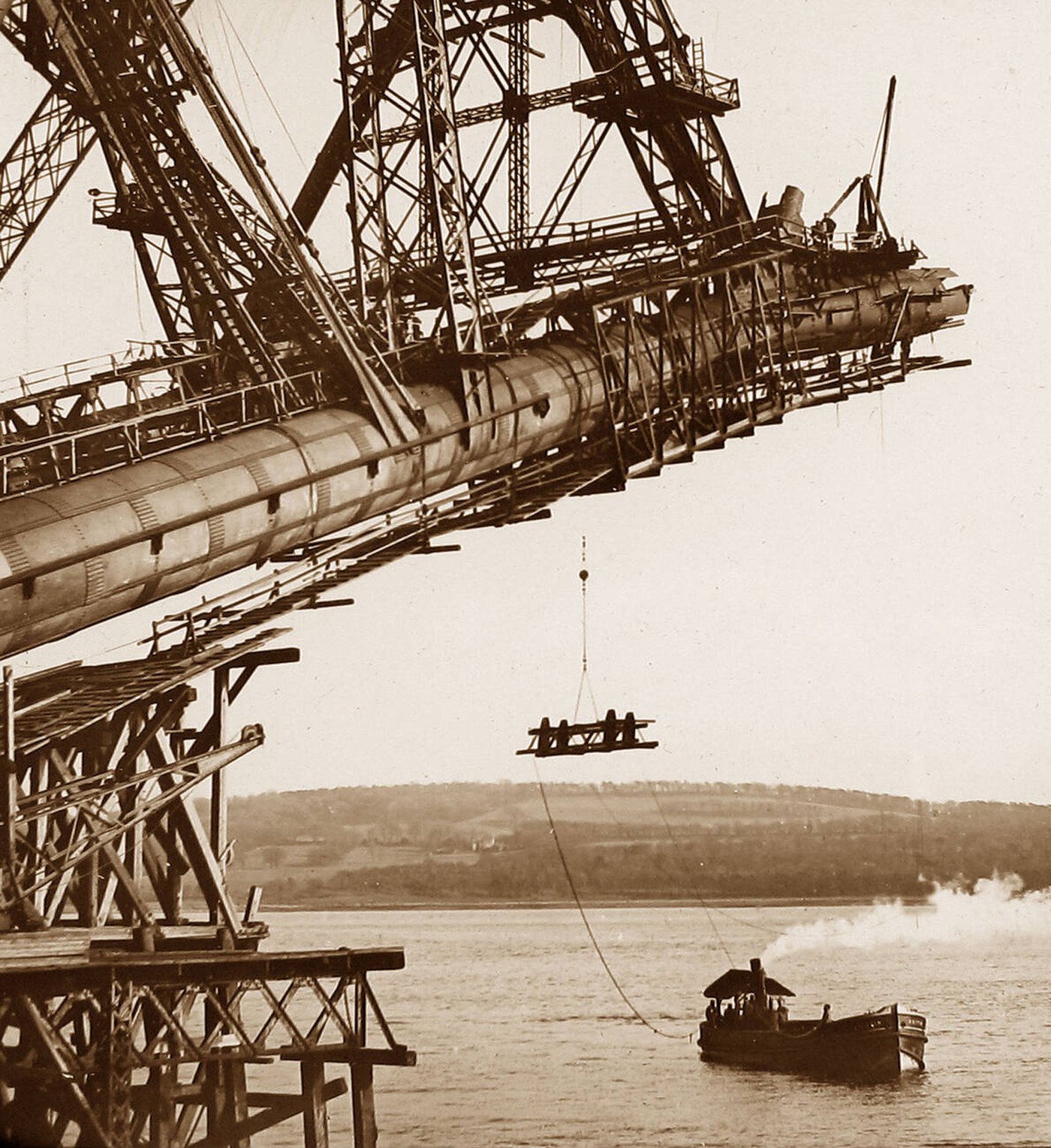

Superstructure assembly started in 1886. Cantilevers extended from the piers. Towers built upward first, then arms reached out. Plates heated in gas furnaces and bent on mandrels. Hydraulic riveters fixed them in place. The bridge used 55,000 tonnes of steel. Siemens Landore supplied 12,000 tonnes. The Steel Company of Scotland and Dalzell’s provided the rest. Rivets totaled 6.5 million, weighing 4,200 tonnes.

The workforce peaked at 4,600 men, called Briggers. They earned above-average wages. The Sick and Accident Club offered medical care and payments for injuries. Safety boats saved eight from drowning. Shelters, heated dining rooms, and gear like waterproofs helped. A log book noted 26,000 accidents and illnesses. Serious cases left hundreds crippled. Deaths reached 73, from falls, crushing, drowning, and caisson disease.

Challenges hit hard during building. The silty riverbed made foundations tricky. Compressed air in caissons caused health issues like the bends. Weather delayed work, with gales testing the structure. The tilted caisson set back the south pier. Safety rules grew strict after Tay, leading to overbuilt sections. Materials moved by barges and trains from Edinburgh.

The bridge completed in December 1889. Load tests in January 1890 used trains weighing 1,880 tons. The first crossing happened in February. Official opening came on March 4, 1890, by the Prince of Wales.

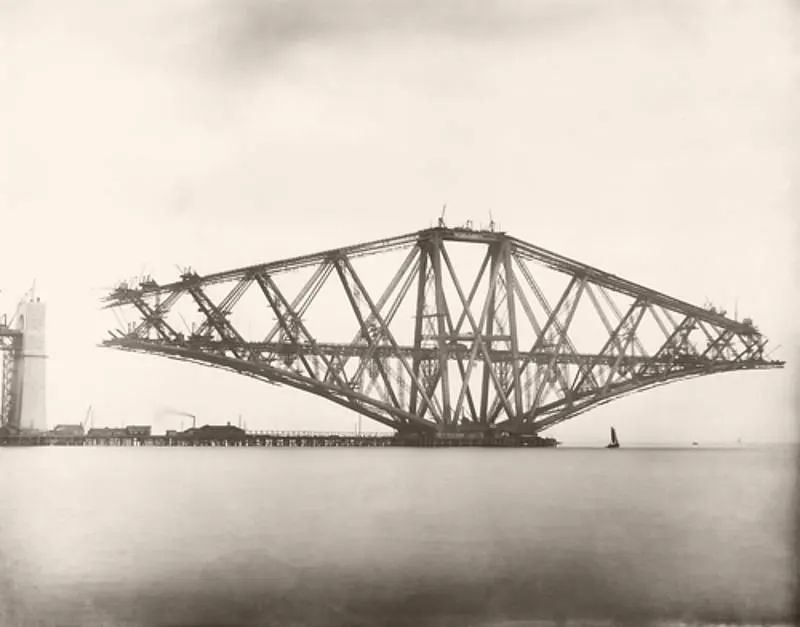

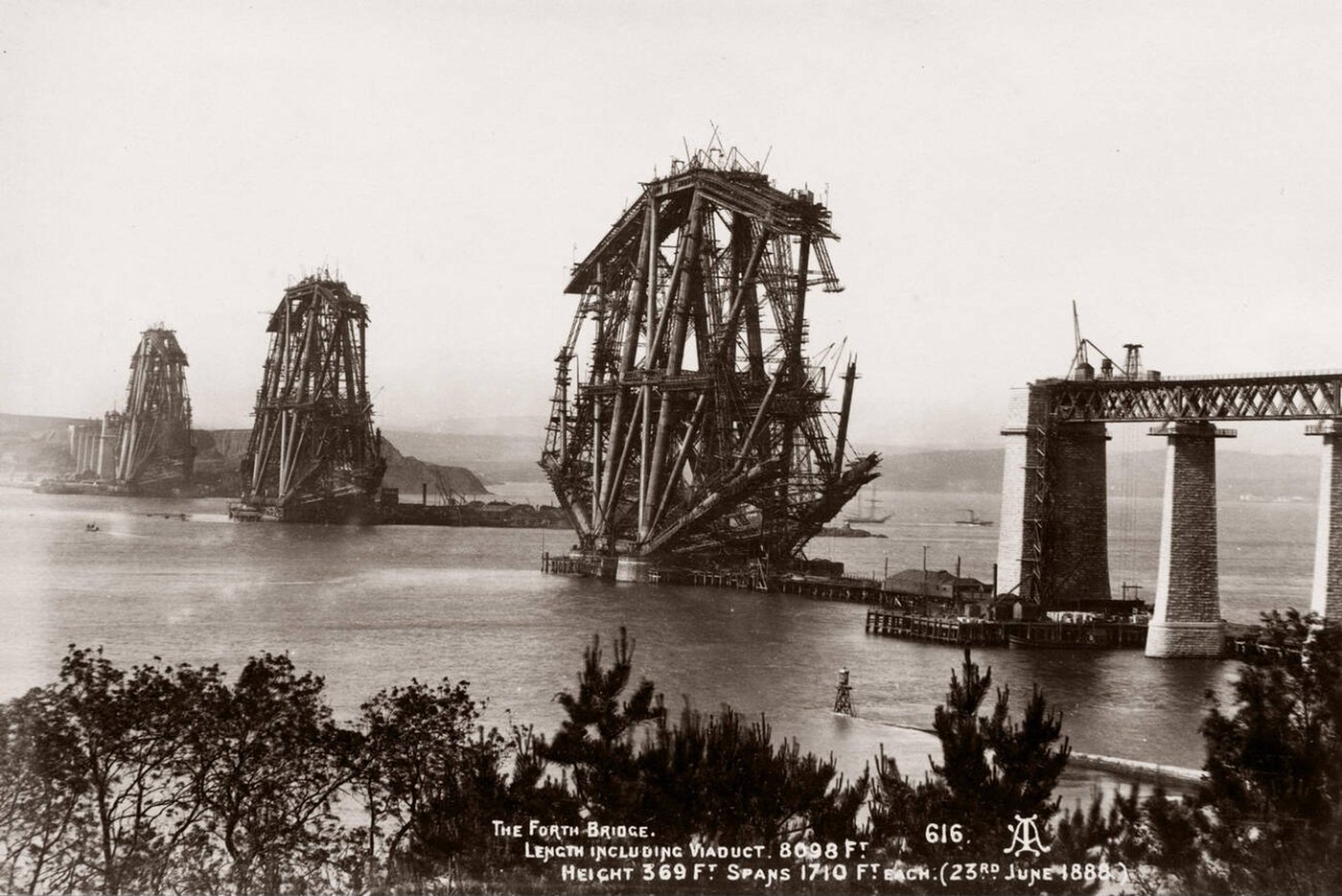

Historical photos capture the process in detail. One from October 1888 shows the Fife cantilever rising with steel tubes in place. Sheets form the structure under clear skies. Another illustrates the cantilever principle with men balancing on sticks. It highlights the design’s core idea.

Images inside caissons reveal tight spaces. Workers dig in dim light with tools scattered. A 1887 view from South Queensferry displays towers growing tall. Scaffolds cling to the sides as arms start to extend.

By 1888, photos show towers nearly done. Arms reach out over water, defying gravity. A 1890 section cuts into a caisson interior. It exposes iron walls and foundation layers.

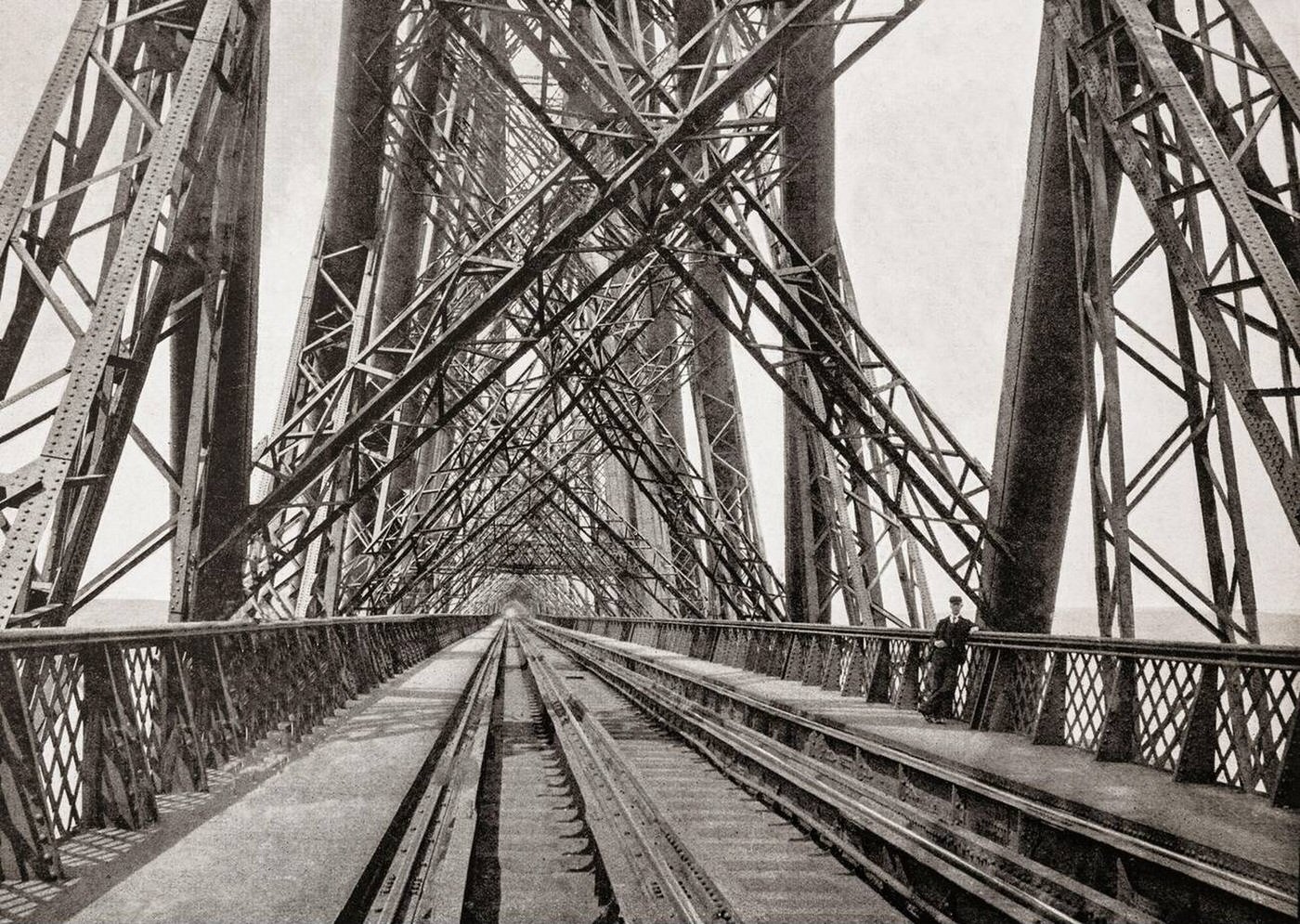

Evelyn George Carey’s series tracks growth from parts to whole. Thousands of shots from fixed spots show components joining into 1,630 meters of steel. Stereographs add depth, like one from 1896 looking through the bridge. Figures in foreground scale the vast spans.