The telephone has been a fixture in the White House for over a century, evolving from a simple novelty into an indispensable tool of presidential power. The way presidents have used this technology, from making their first calls to conducting critical international negotiations, reflects the changing nature of the office itself.

The First Connections

The first telephone was installed in the White House in 1877 during the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes. It was placed in the Telegraph Room and had the simple phone number “1.” President Hayes was not an avid user of the new invention; the first call he placed was to the telephone’s inventor, Alexander Graham Bell, who was 13 miles away. For many years, the device was not seen as essential. President William McKinley, for instance, had a secretary place and answer all calls for him.

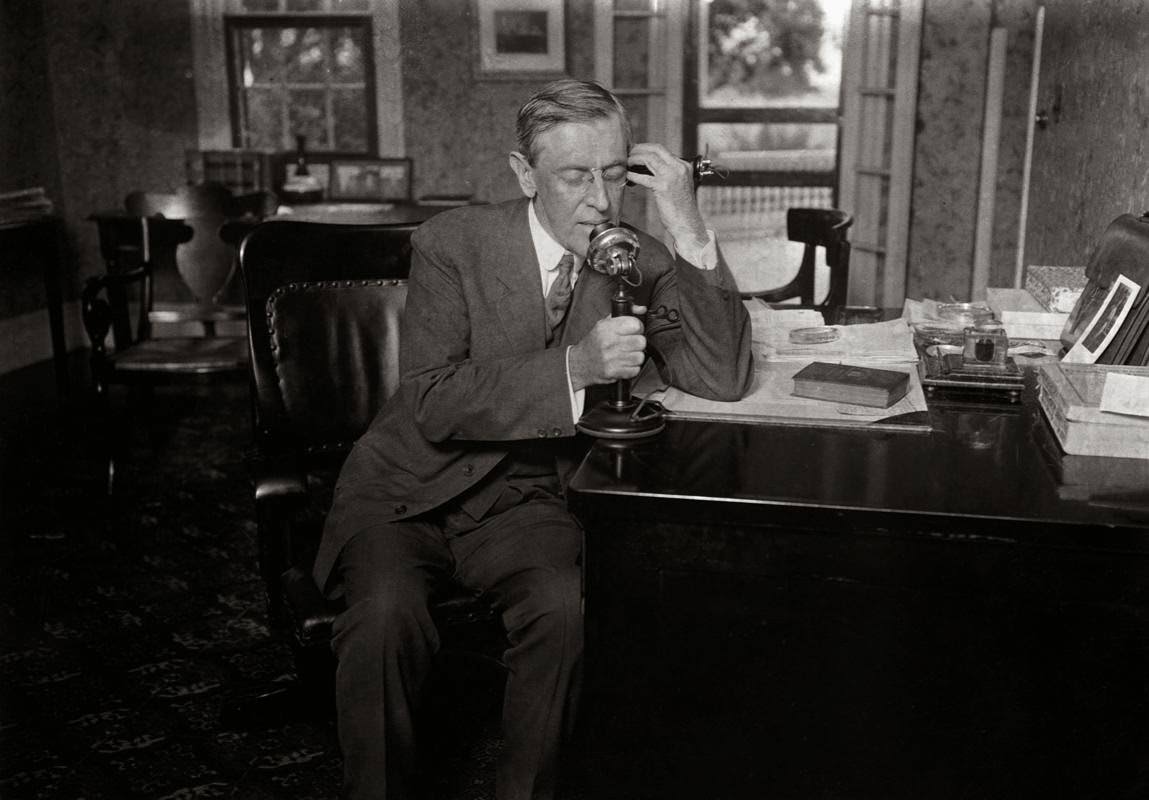

The first president to have a telephone line directly on his desk was Herbert Hoover in 1929. Before this, if a president wished to make a call from his office, a telephone had to be physically brought to him from another room. Hoover’s decision to have a permanent phone in the Oval Office marked a shift in how the technology was viewed, turning it from a staff-operated tool into a personal instrument of the presidency.

Read more

The Phone as a Tool of Power

Franklin D. Roosevelt fully embraced the telephone as a means of governing. He had multiple lines installed on his desk, including secure lines for sensitive communications during World War II. Roosevelt used the phone extensively to speak with advisors, members of Congress, and world leaders. He also understood the importance of recording conversations for historical accuracy and had a recording device connected to his phone in the White House Map Room.

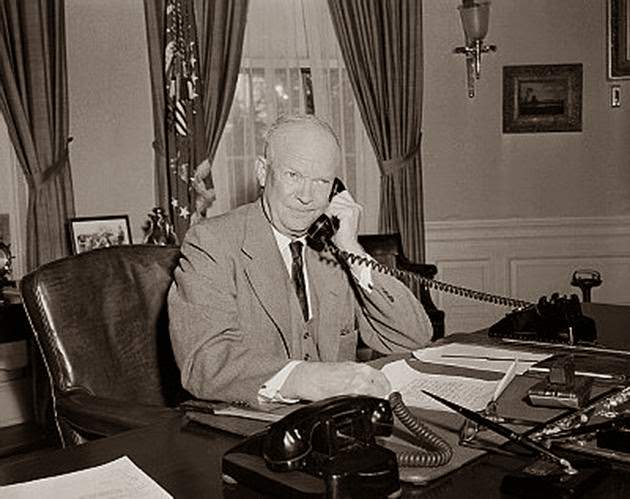

His successor, Harry S. Truman, continued this practice. Truman often used the phone for blunt, direct conversations. A famous photograph shows him on the phone at his desk, and his administration also recorded select conversations, providing a clear record of his decision-making process during the early years of the Cold War.

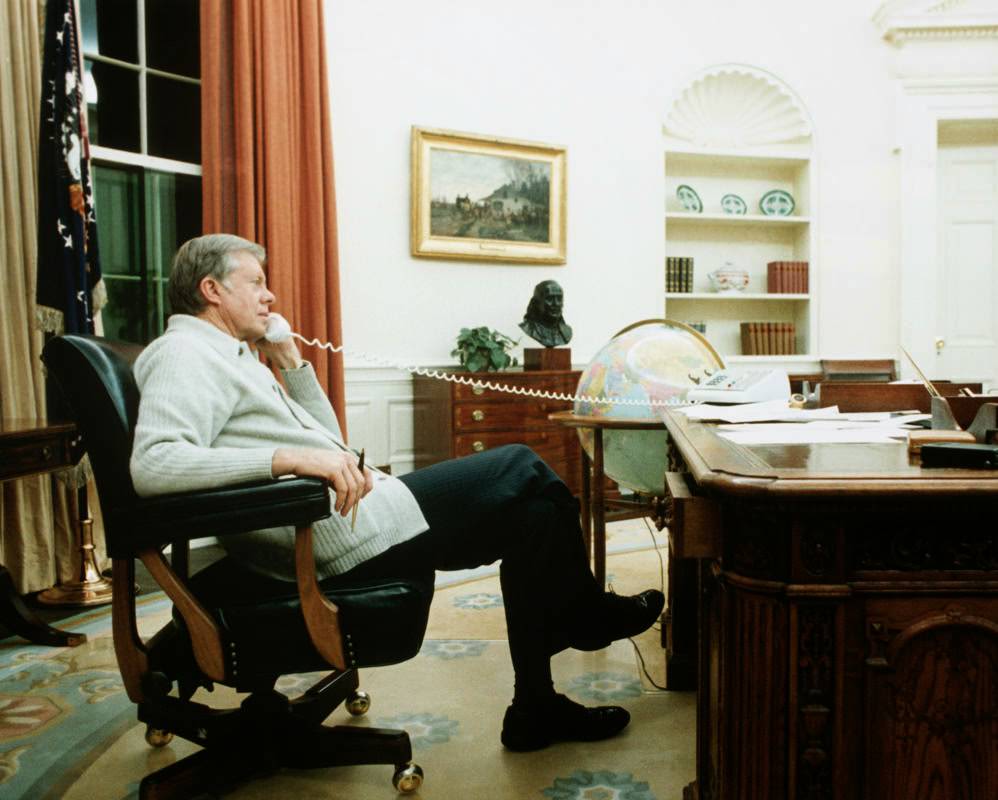

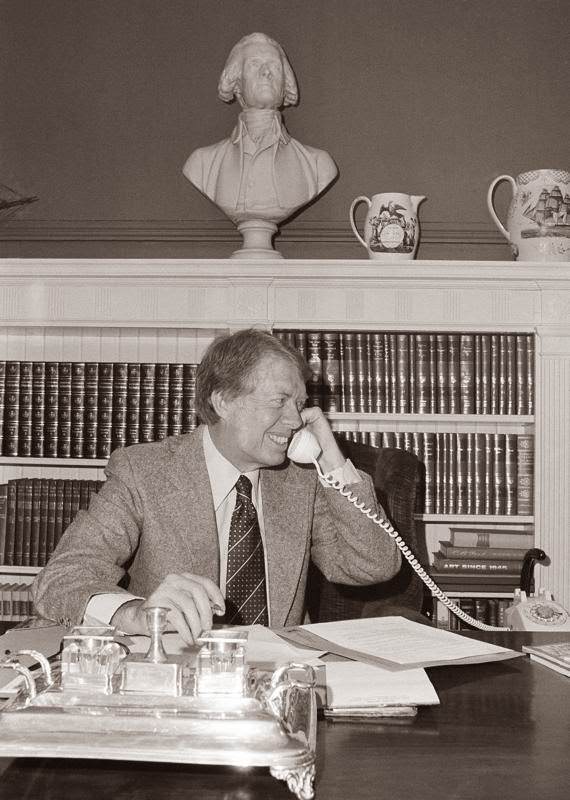

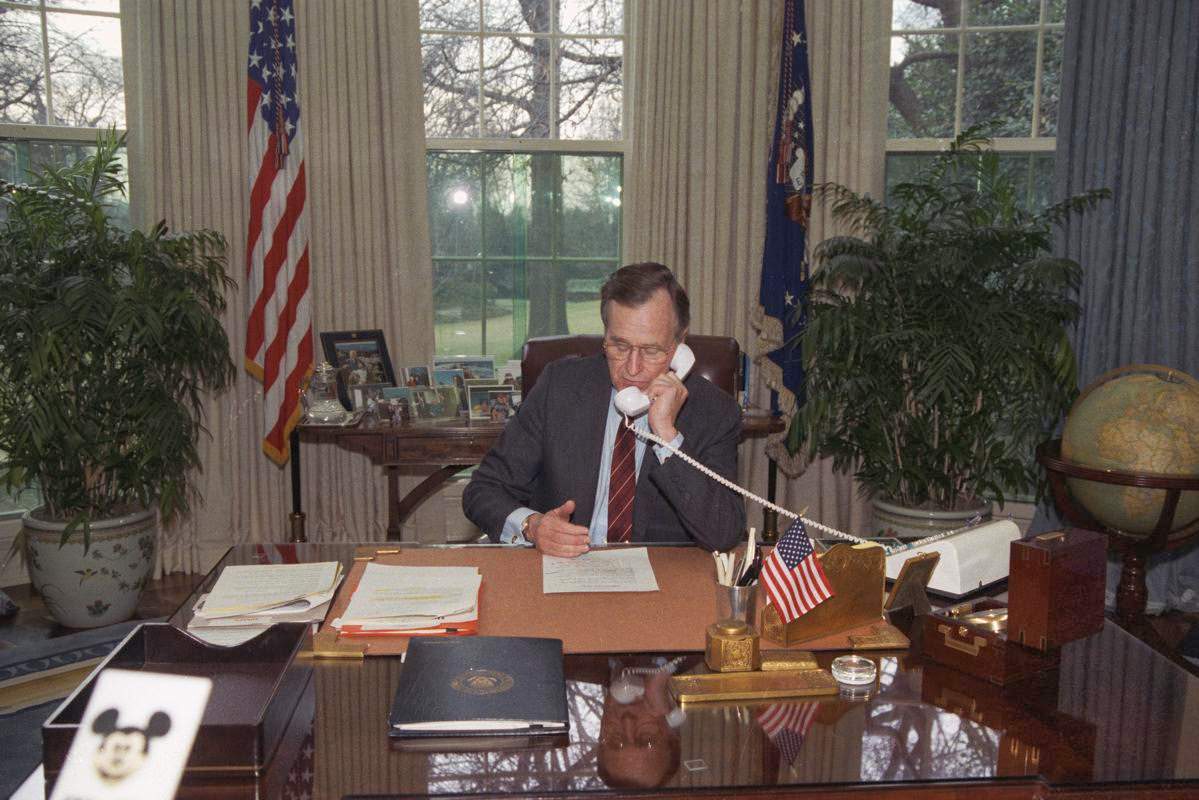

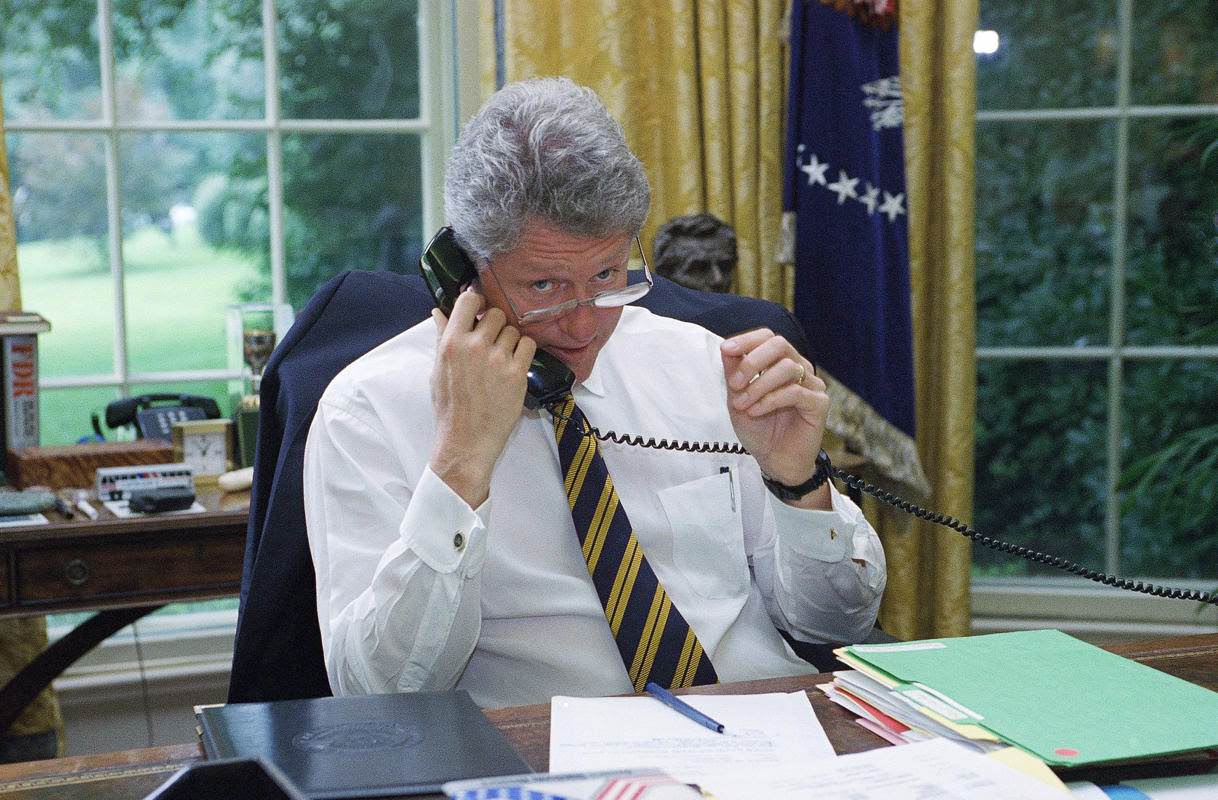

The Modern Presidential Call

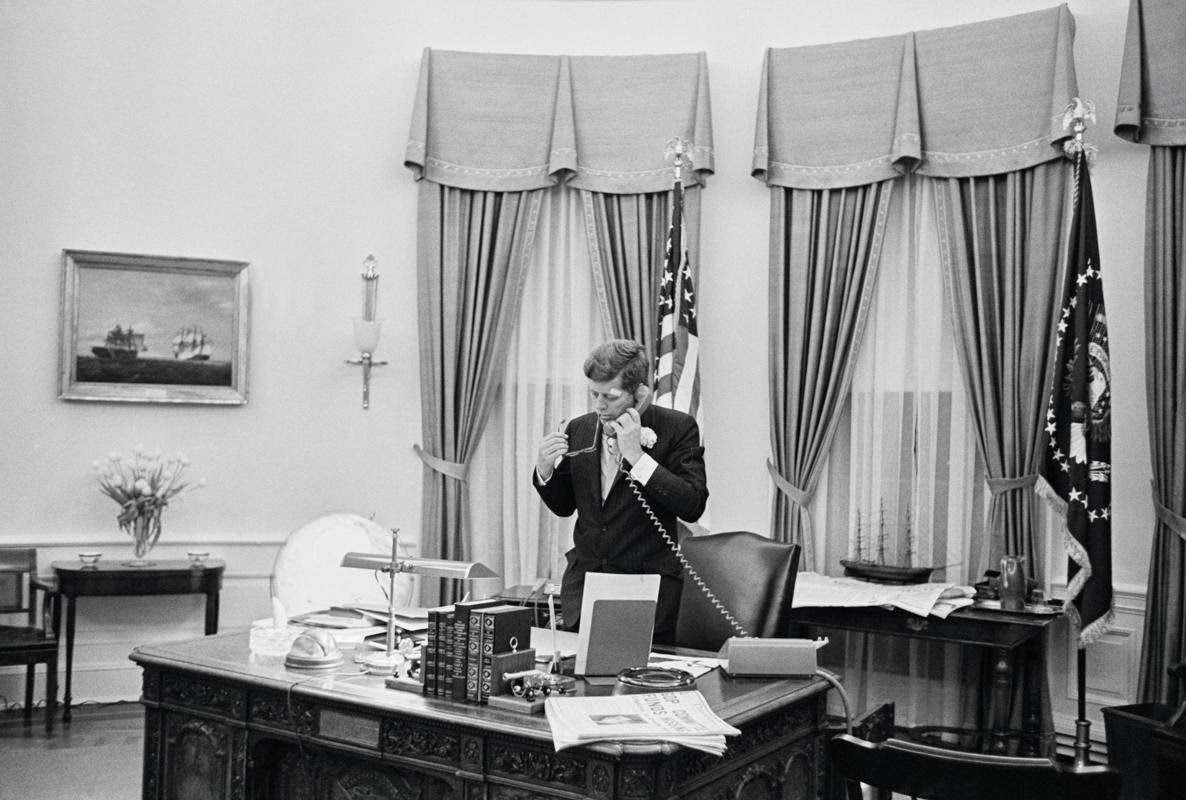

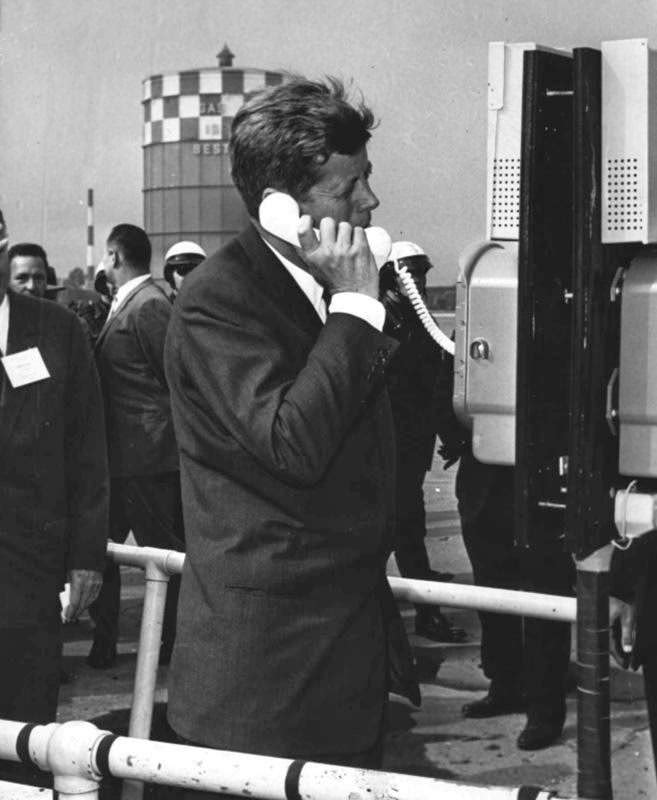

By the mid-20th century, the telephone was central to the presidency. John F. Kennedy’s administration relied heavily on telephone communication during the tense 13 days of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. Kennedy was in constant contact with his advisors in the Executive Committee (ExComm), military leaders, and diplomats as they navigated the standoff with the Soviet Union.4 Kennedy also secretly recorded many of his phone calls and meetings, a practice intended to aid future historians.

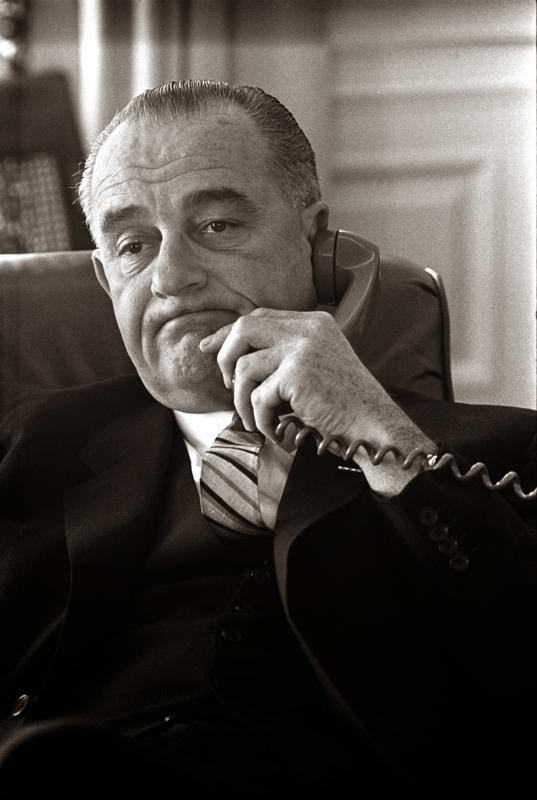

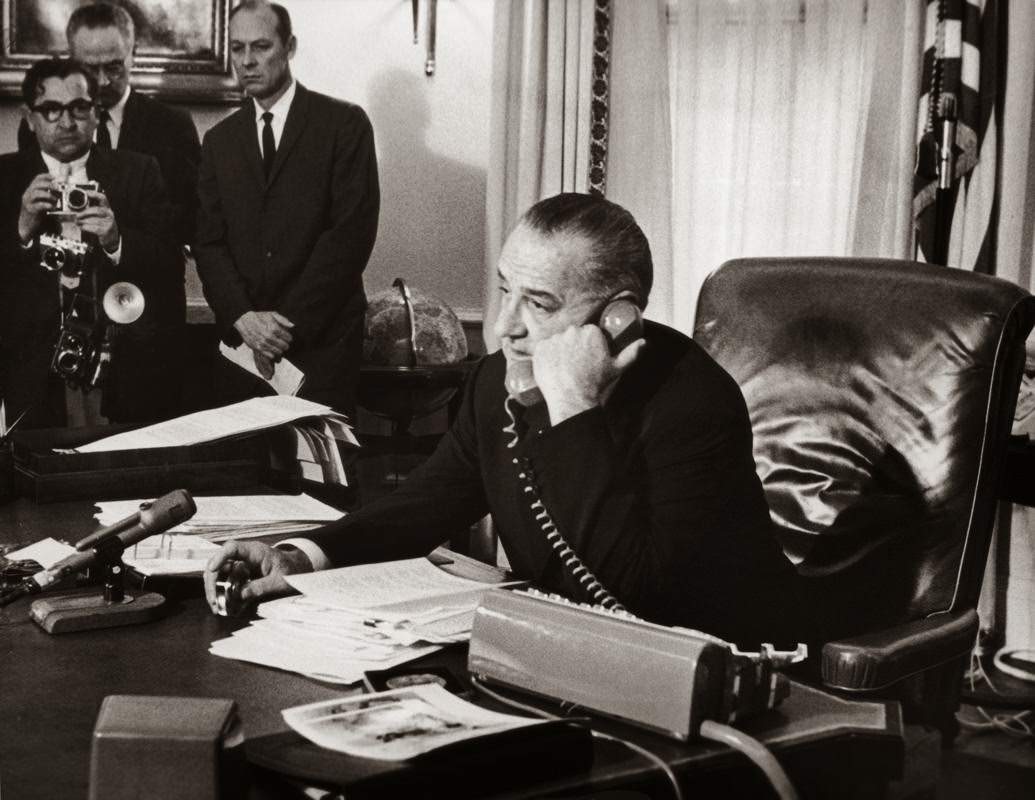

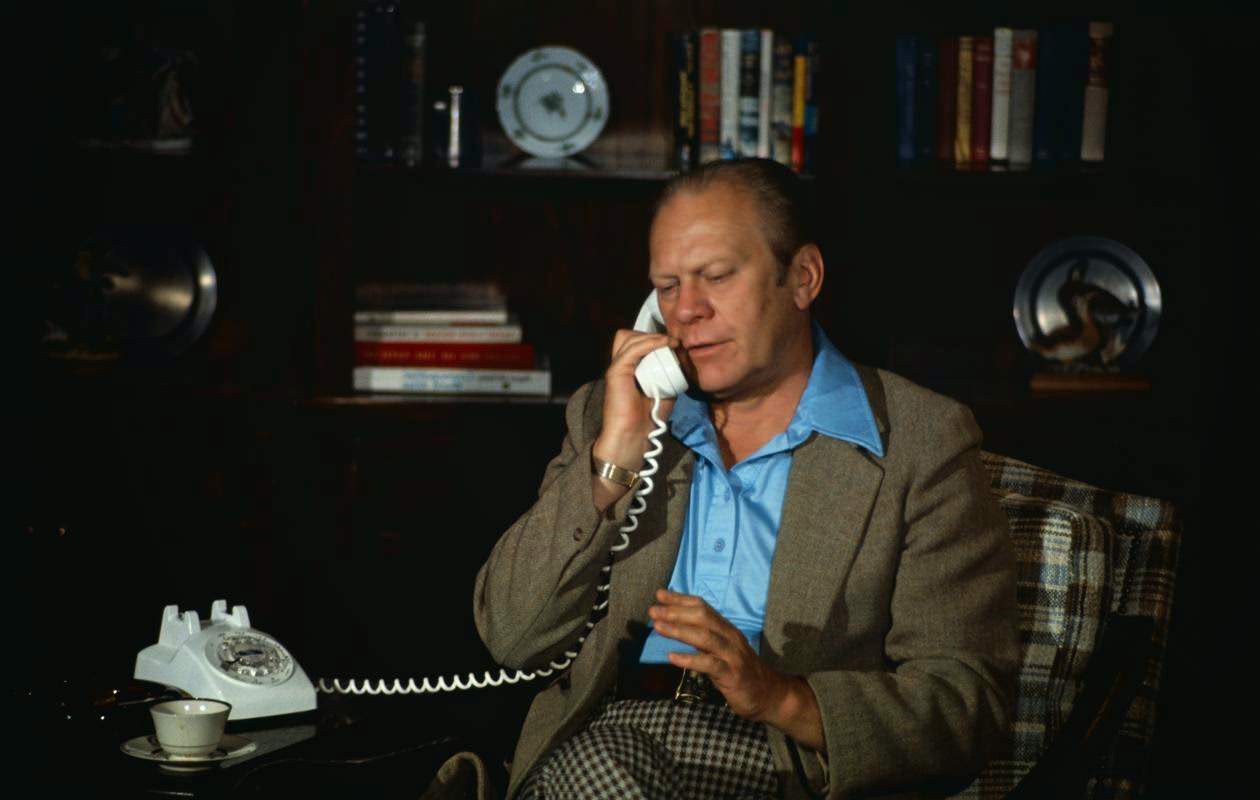

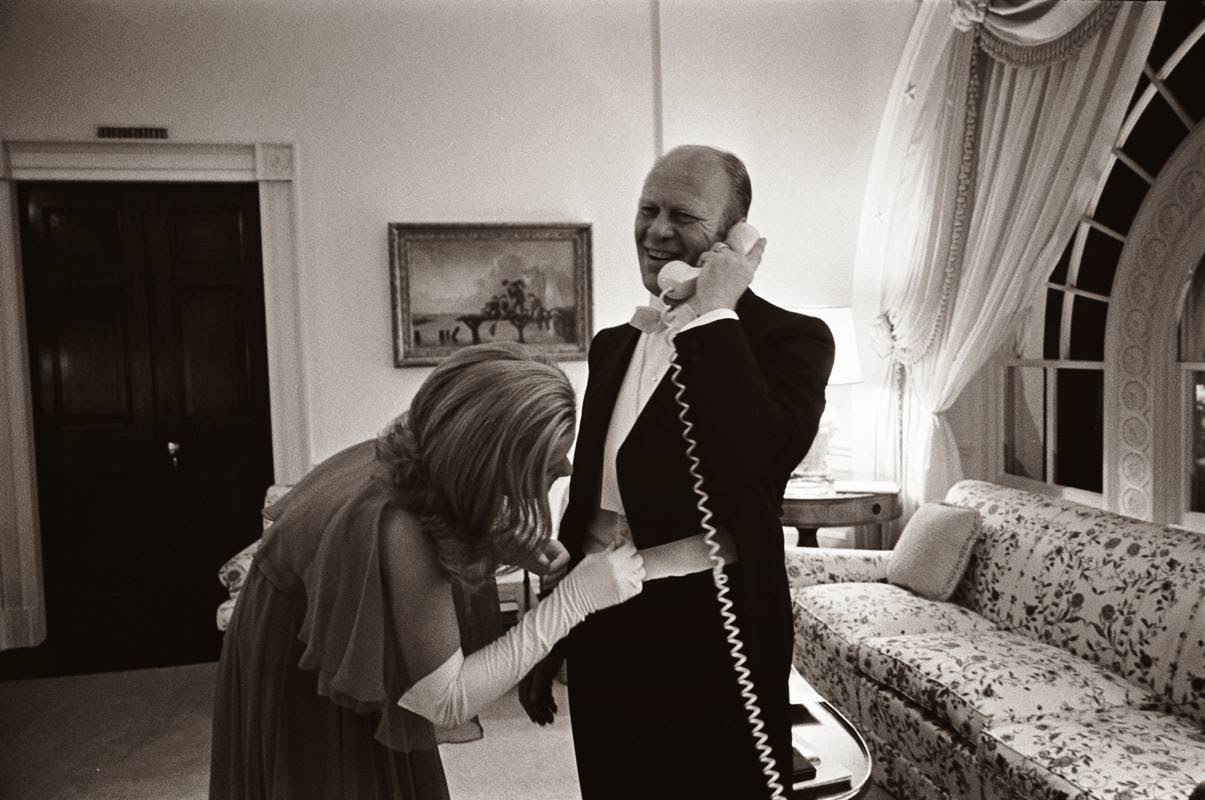

Lyndon B. Johnson was a master of using the telephone for political persuasion. Known for his “Johnson Treatment,” he would use the phone to cajole, flatter, and pressure members of Congress to support his Great Society legislation. Johnson had phones installed everywhere, including in the bathroom and on his boat. His recorded calls reveal a president intimately involved in the details of lawmaking, using the phone as his primary weapon for building consensus and twisting arms. The image of a president on the phone, whether in a moment of crisis or a routine check-in, became a standard depiction of the modern American leader at work.