Motor-paced racing is a form of bicycle racing that uses a special technique to achieve high speeds. It involves a cyclist riding very closely behind another vehicle or even another cyclist. The main idea is for the cyclist to use the air pushed aside by the vehicle or person in front.

The key to motor-paced racing is something called the “slipstream,” or sometimes “drafting.” When a vehicle or person moves through the air at speed, they create an area of reduced air pressure and turbulence directly behind them. This pocket of disturbed air is the slipstream. If a cyclist can ride closely inside this slipstream, the air resistance they face is greatly reduced. Air resistance is a major force that slows cyclists down, especially as they go faster. By riding in the slipstream, the cyclist can travel much faster with significantly less effort than if they were riding alone at the same speed.

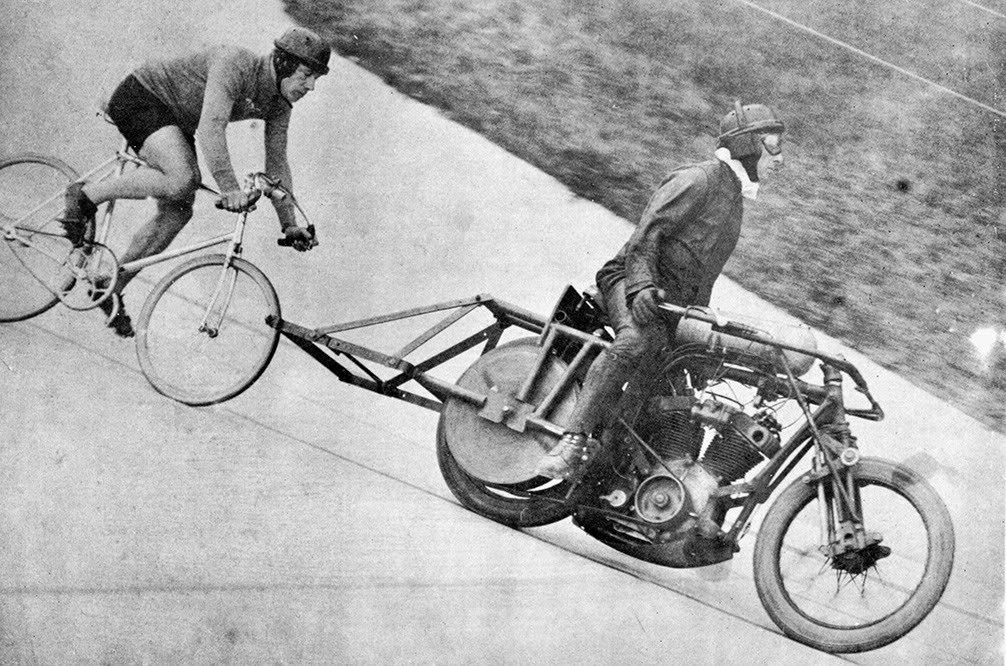

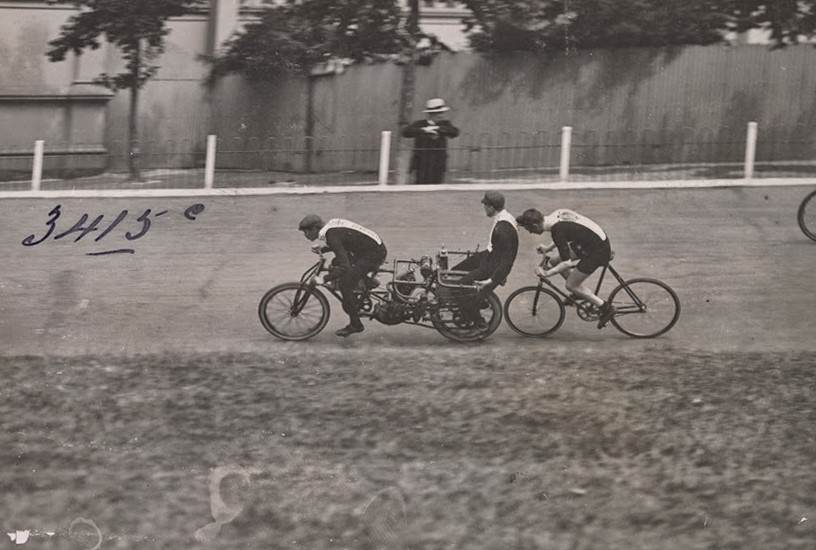

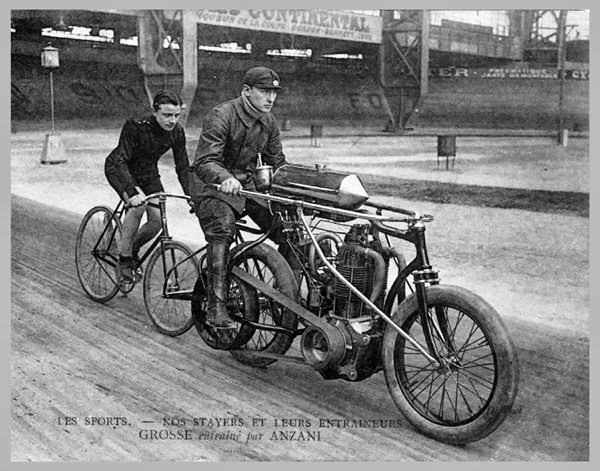

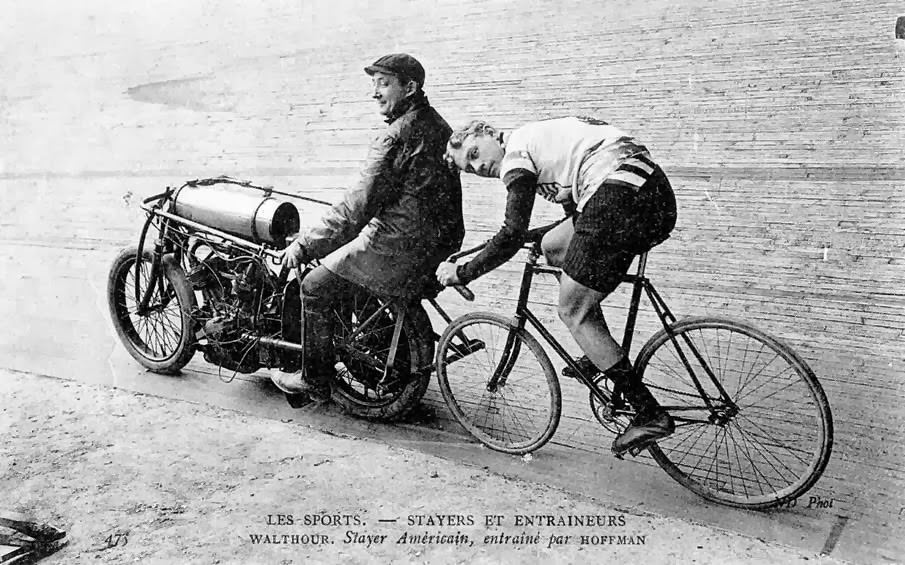

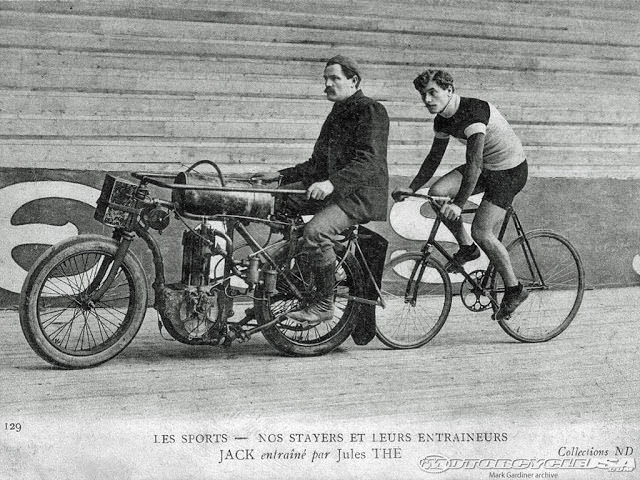

The vehicle or person in front is called the “pacer.” The pacer’s job is to move through the air ahead of the cyclist, creating that crucial slipstream. The pacer sets the speed, and the cyclist has to maintain their position right behind them, often just inches away from the back of the pacer’s vehicle. This requires incredible skill and focus from the cyclist.

Today, the most common type of pacer used in this sport is a motorcycle. These motorcycles are often specially designed or modified for paced cycling. They might have a roller or a special bar on the back for the cyclist to follow even more closely, or enlarged fairings to create a bigger slipstream. The rider on the motorcycle is also a skilled pacer, working carefully with the cyclist to maintain a consistent speed and line.

Cars have also been used as pacers. The context mentions that for certain long-distance races like Bordeaux-Paris and for attempts to set cycling speed records, cars have served as the lead vehicle. A car provides a larger slipstream than a motorcycle, which can be beneficial, especially at very high speeds or on open roads.

Historically, before motorized vehicles became common for pacing, other methods were used. The context notes that the earliest paced races were sometimes behind other cyclists. In some cases, multiple riders would ride together on a single tandem bicycle – sometimes as many as five riders on one large tandem – to create a significant slipstream for the cyclist behind them. This shows how the fundamental idea of using a pacer for speed has evolved over time.

The cyclist riding behind the pacer faces a demanding challenge. They need exceptional bike handling skills to maintain balance and control while riding mere inches behind a moving vehicle at high speeds. Constant concentration is required to stay precisely in the slipstream and avoid touching the pacer’s wheel or body. The physical effort is still intense, but the advantage gained from the reduced air resistance allows the cyclist to sustain speeds that would be impossible on their own.

Motor-paced racing allows for truly remarkable speeds on a bicycle. Because the pacer takes on the majority of the work fighting air resistance, the cyclist can focus on pedaling and maintaining speed within the slipstream. While exact speeds depend on the event and conditions, paced cyclists can reach speeds significantly higher than those in unpaced races, often exceeding 50 or 60 miles per hour, particularly when paced by a powerful motor.

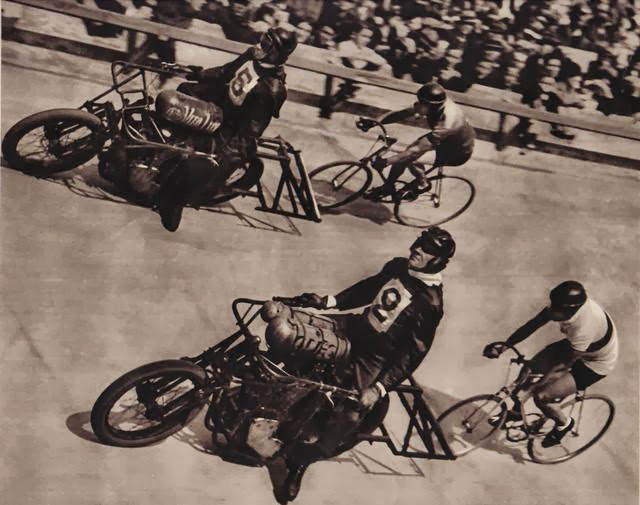

This type of racing is typically held in specific locations. Velodromes, which are specially built tracks with steeply banked turns, are common venues. The banking allows cyclists to maintain high speeds through the curves without being pushed outwards by centrifugal force. Some historic motor-paced races, like the Bordeaux-Paris event mentioned, took place on public roads, covering long distances between cities.

Motor-paced cycling is used for different purposes, as noted in the context. It is a competitive sport in itself, with races featuring multiple paced cyclists competing against each other. It is also used by cyclists attempting to break speed records, pushing the boundaries of how fast a bicycle can go. Additionally, it serves as a training method for cyclists to develop leg speed, endurance, and the mental toughness required to ride at very high speeds.

The visual of motor-paced racing is quite dramatic. You see the pacer’s vehicle, often a powerful and distinctively modified motorcycle, leading the way. Tucked tightly behind is the cyclist, leaning low over their handlebars, focused intently on the pacer’s back wheel. The speed at which they pass is impressive, and the close proximity creates a sense of tension and skill. Cyclists often wear specialized gear, including leather suits, for protection at high speeds.

Riding at high speeds just inches behind a motorized vehicle inherently carries risks. If the cyclist makes a mistake, touches the pacer, or has a mechanical issue, the consequences can be serious due to the speeds and close spacing. This element of danger adds to the intensity and challenge of the sport.

Motor-paced racing is a specialized cycling discipline built around the principle of using a pacer’s slipstream for speed. It demands exceptional skill from both the pacer and the cyclist and allows bicycles to reach speeds far beyond what is possible when riding alone. It is a visually exciting sport practiced in races, record attempts, and training.