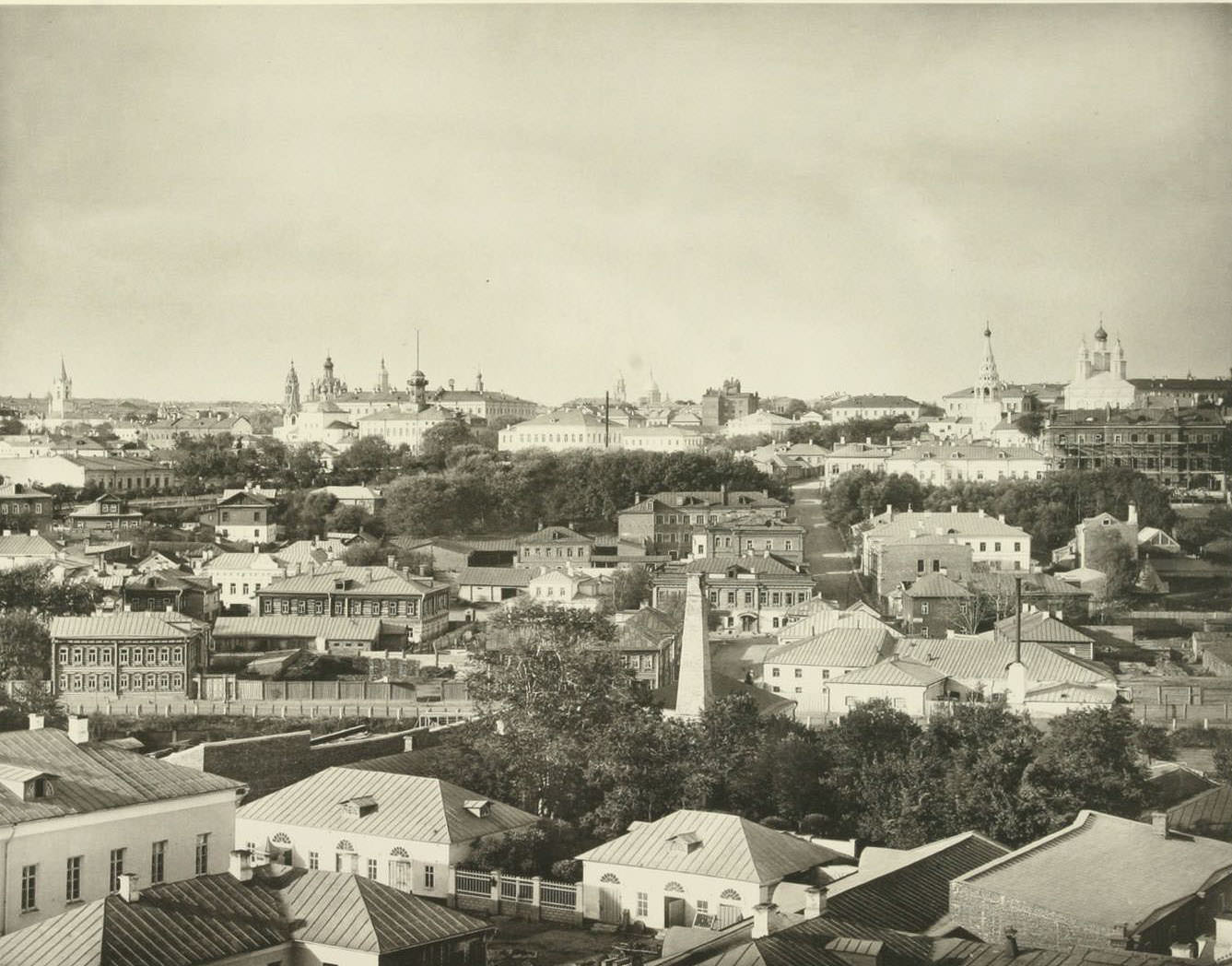

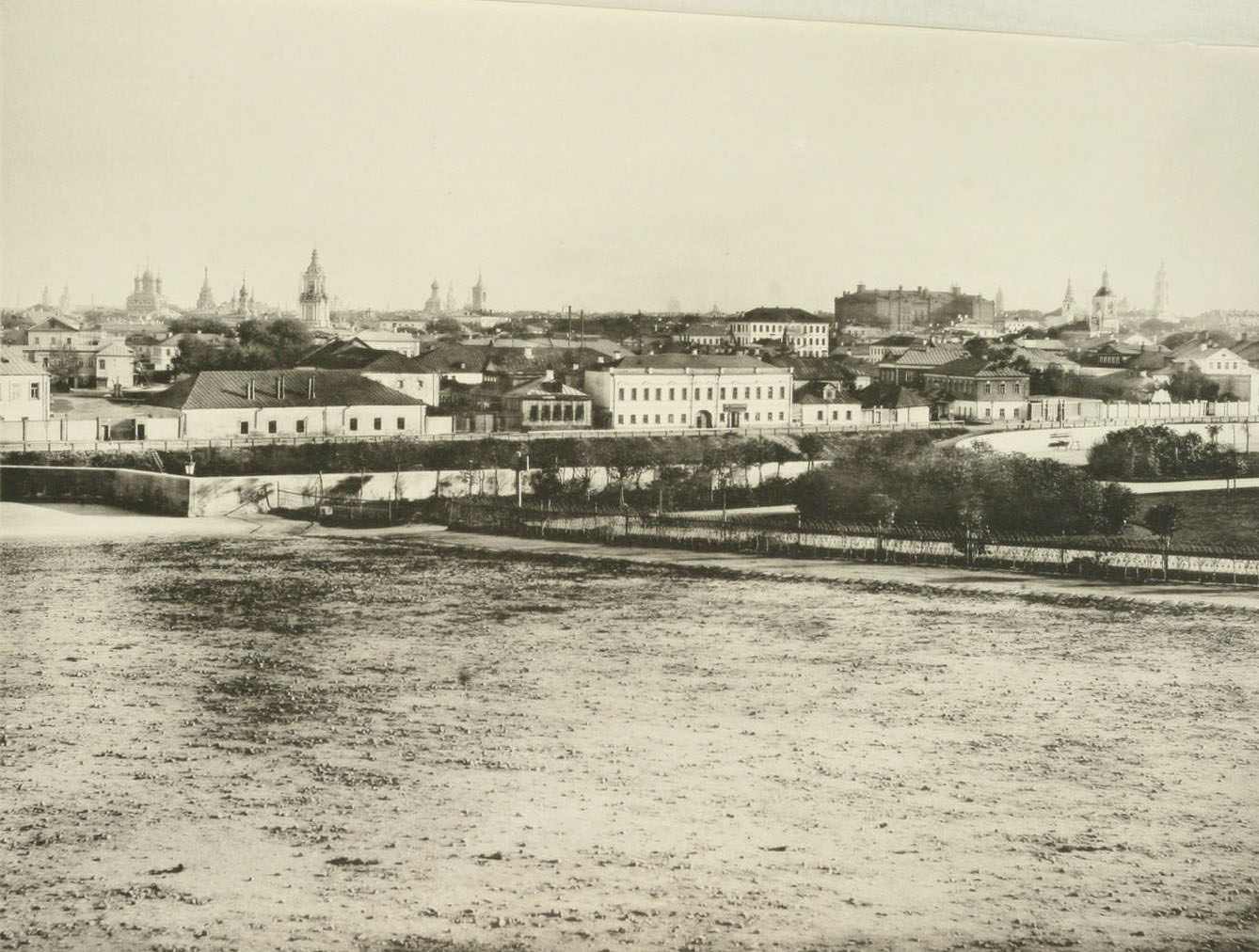

Moscow in the 1880s housed 753,469 people within its ancient walls and expanding suburbs. The city stretched across both banks of the Moskva River, with the Kremlin fortress at its heart. Red Square served as the main marketplace and gathering point, where St. Basil’s Cathedral displayed its colorful onion domes against the sky.

The decade began under Tsar Alexander II’s reforms, but his assassination in 1881 brought his son Alexander III to power. The new tsar reversed many liberal policies and tightened control over the empire. Moscow’s governor-general enforced strict censorship laws and monitored political gatherings.

Streets and Neighborhoods

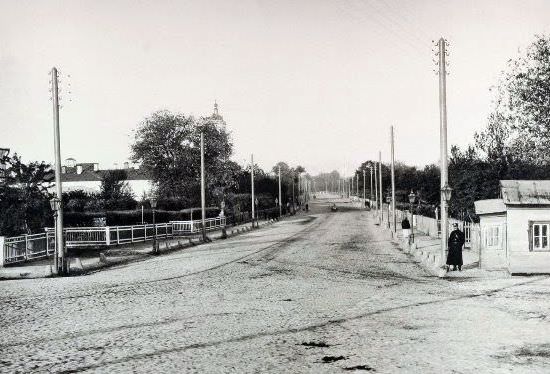

Tverskaya Street ran north from the Kremlin as Moscow’s main thoroughfare. Wealthy merchants and nobles built three-story mansions along this road, with shops occupying the ground floors. Gas lamps lit the street at night, though most of Moscow still relied on oil lanterns.

The Arbat district housed writers, artists, and university professors. Small wooden houses lined narrow lanes where intellectuals gathered in cramped apartments to discuss literature and politics. Police informers often attended these meetings, reporting suspicious conversations.

Read more

Zamoskvorechye, south of the river, belonged to merchants and traders. Two-story stone houses displayed carved wooden shutters and iron gates. Gardens behind these homes grew vegetables and fruit trees. Orthodox churches dotted every neighborhood—Moscow had 450 churches serving its residents.

Working Life

Factory whistles woke workers at 5 AM. The Prokhorov textile mill employed 8,000 people, mostly women and children who operated spinning machines and looms. Workers earned 15-20 rubles monthly, barely enough to rent a corner of a basement room. Shifts lasted 12-14 hours in poorly ventilated buildings.

The Goujon metalworks produced rails and machinery for Russia’s expanding railroad network. Skilled metalworkers earned higher wages but faced dangerous conditions. Accidents occurred weekly, with no compensation for injured workers.

Small workshops filled courtyards throughout the city. Cobblers, tailors, and furniture makers worked in family businesses passed down through generations. Master craftsmen trained apprentices who lived and worked in the same buildings.

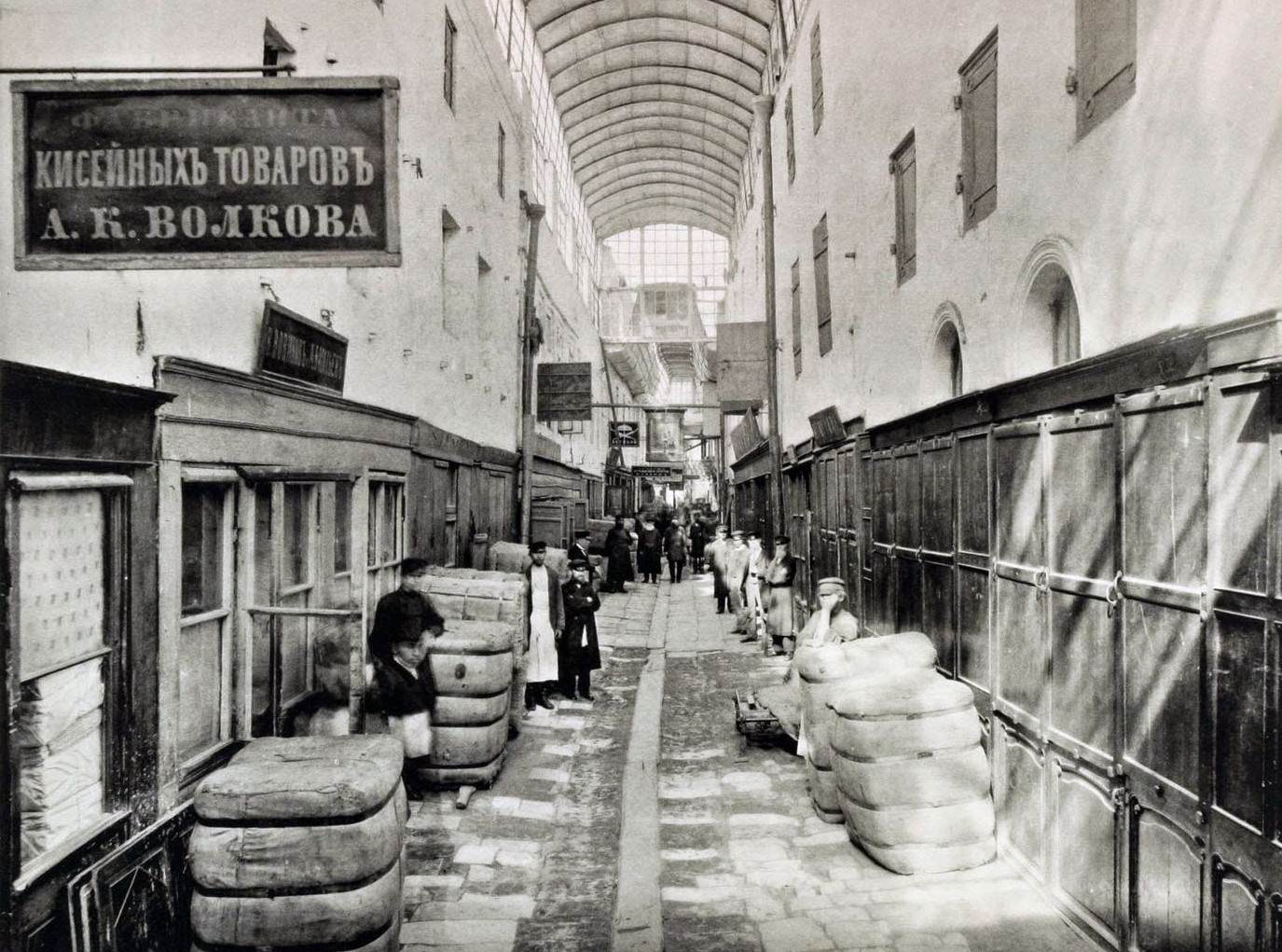

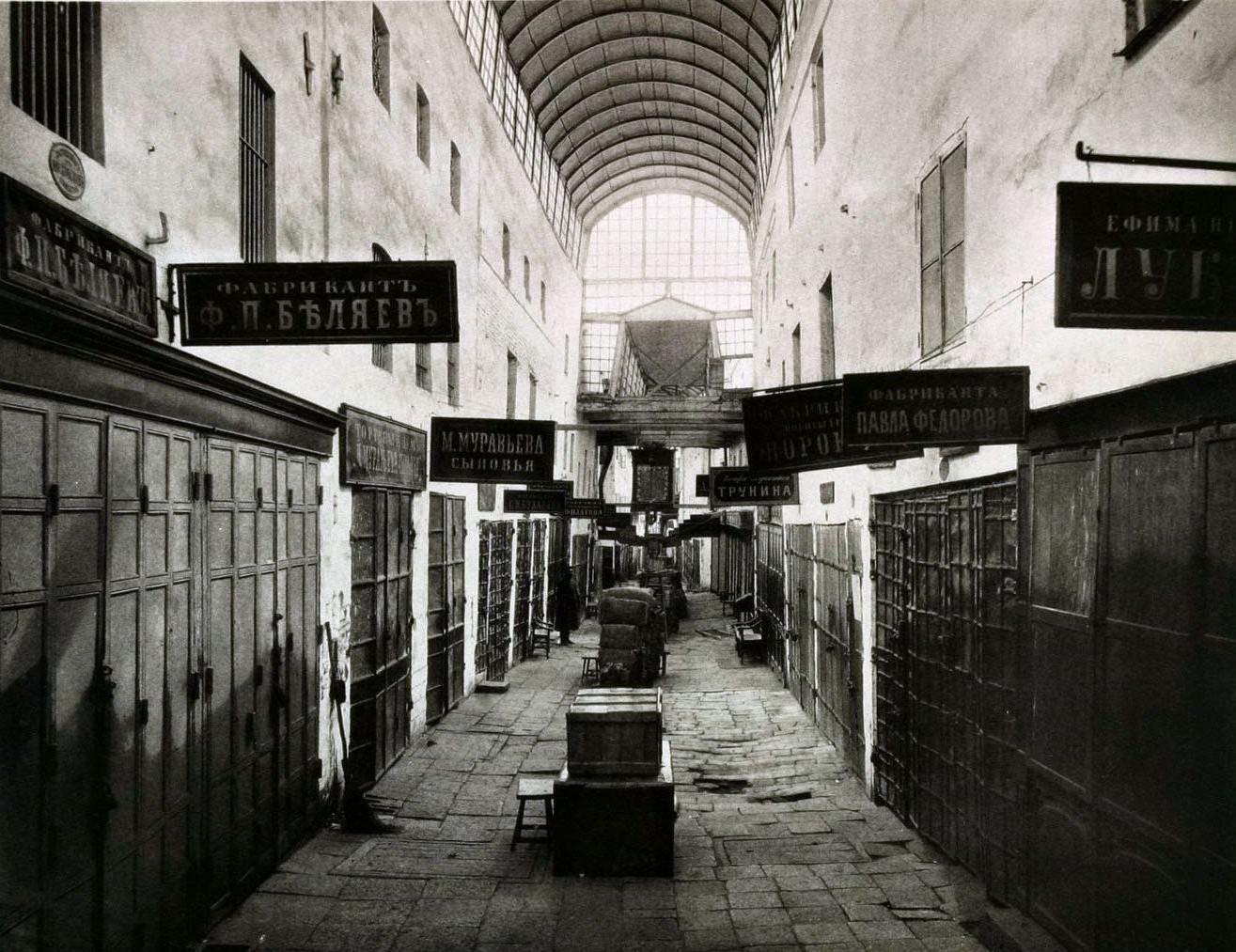

Markets and Trade

The Okhotny Ryad market sprawled across several blocks near Red Square. Vendors sold fish packed in ice, vegetables from nearby farms, and imported goods like coffee and spices. Haggling determined prices, with shoppers inspecting every item carefully.

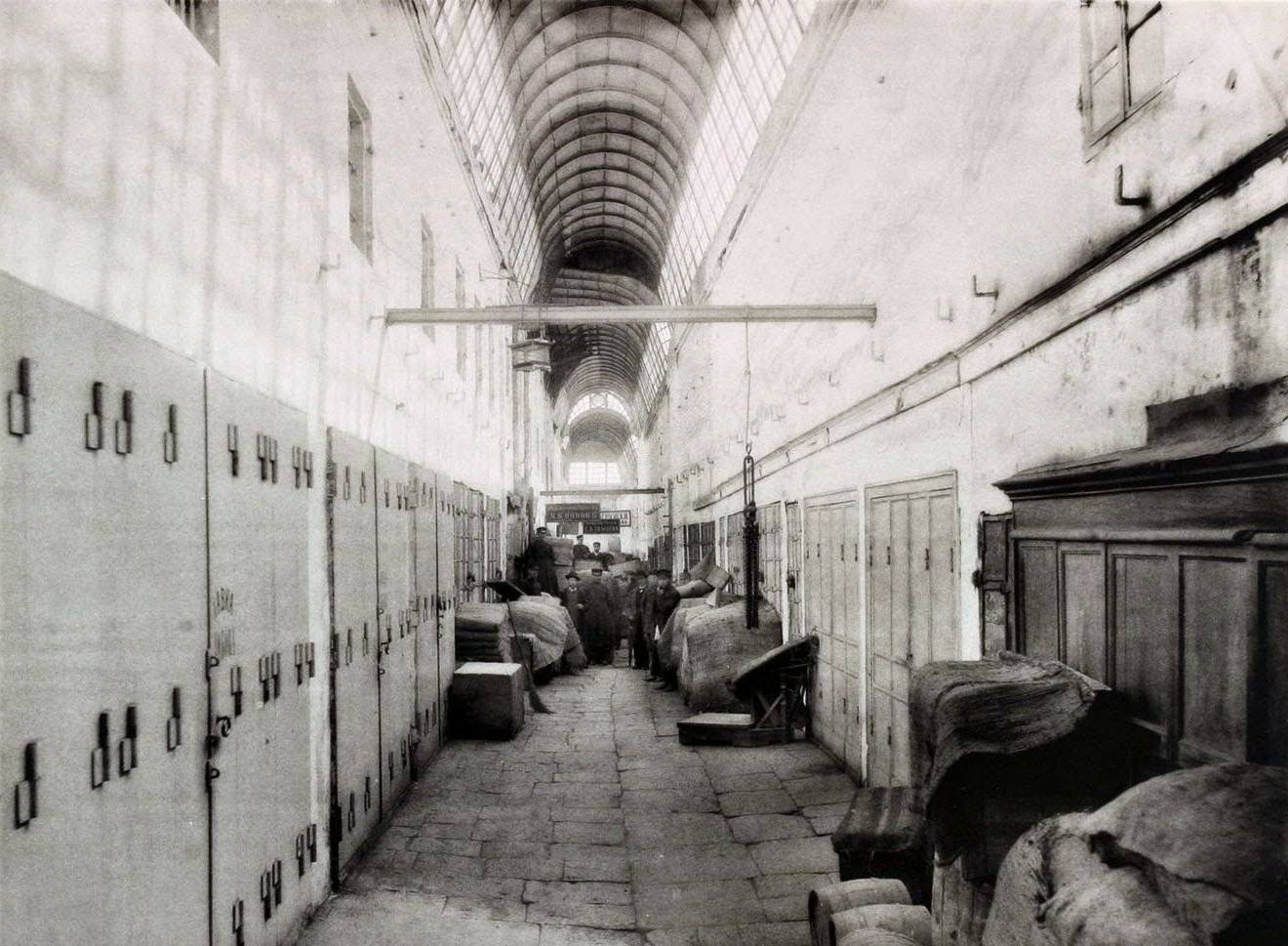

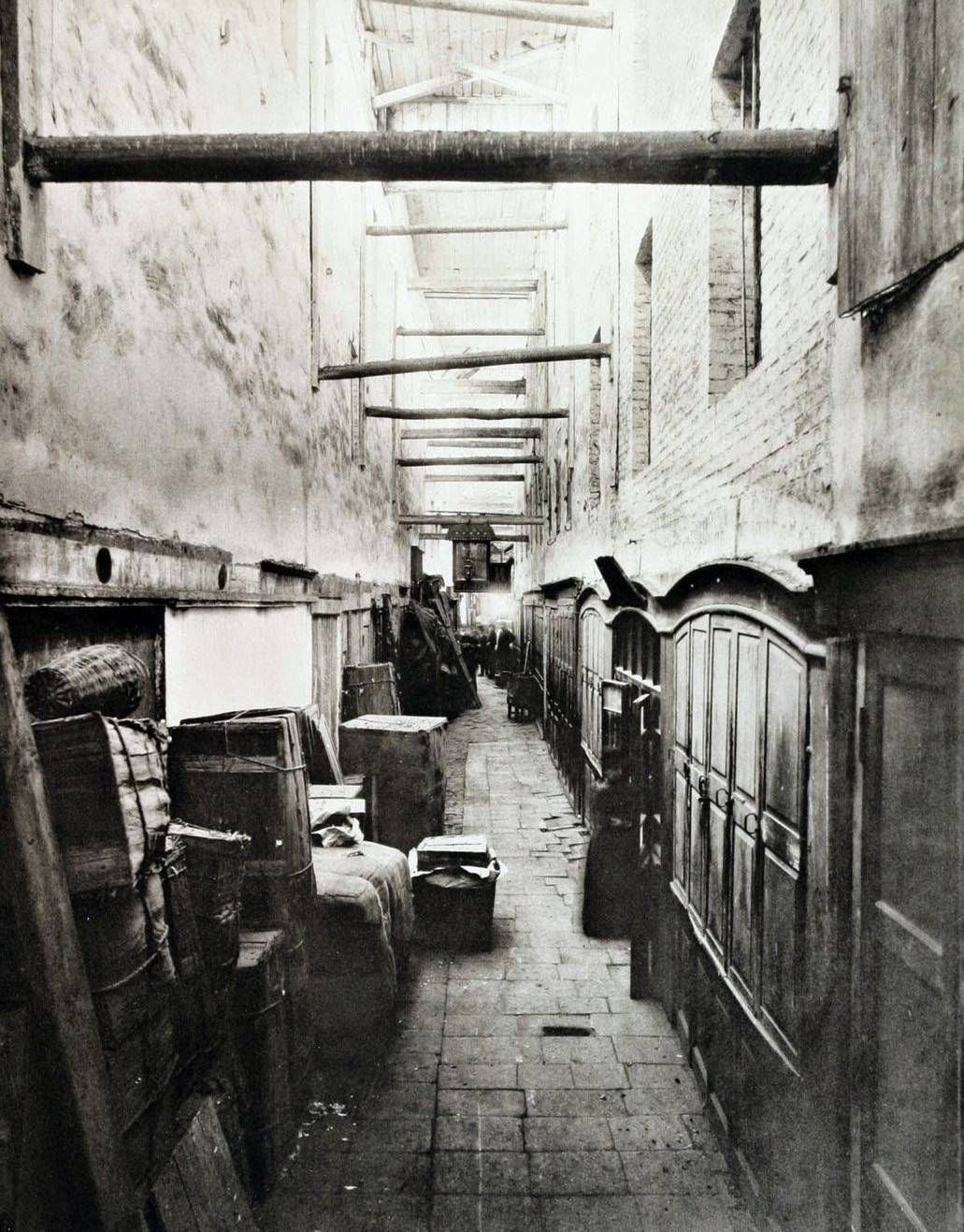

Merchants gathered at the Gostiny Dvor, a massive trading arcade. Persian rugs, Chinese silk, and European machinery changed hands in wholesale deals. Tea merchants dominated trade, importing millions of pounds annually through Siberian caravan routes

Street peddlers carried trays of pirozhki (stuffed pastries), pickled cucumbers, and sunflower seeds. They called out their wares in sing-song voices, competing for customers’ attention. Hot sbiten, a honey-based drink, warmed pedestrians during cold months.

Transportation Changes

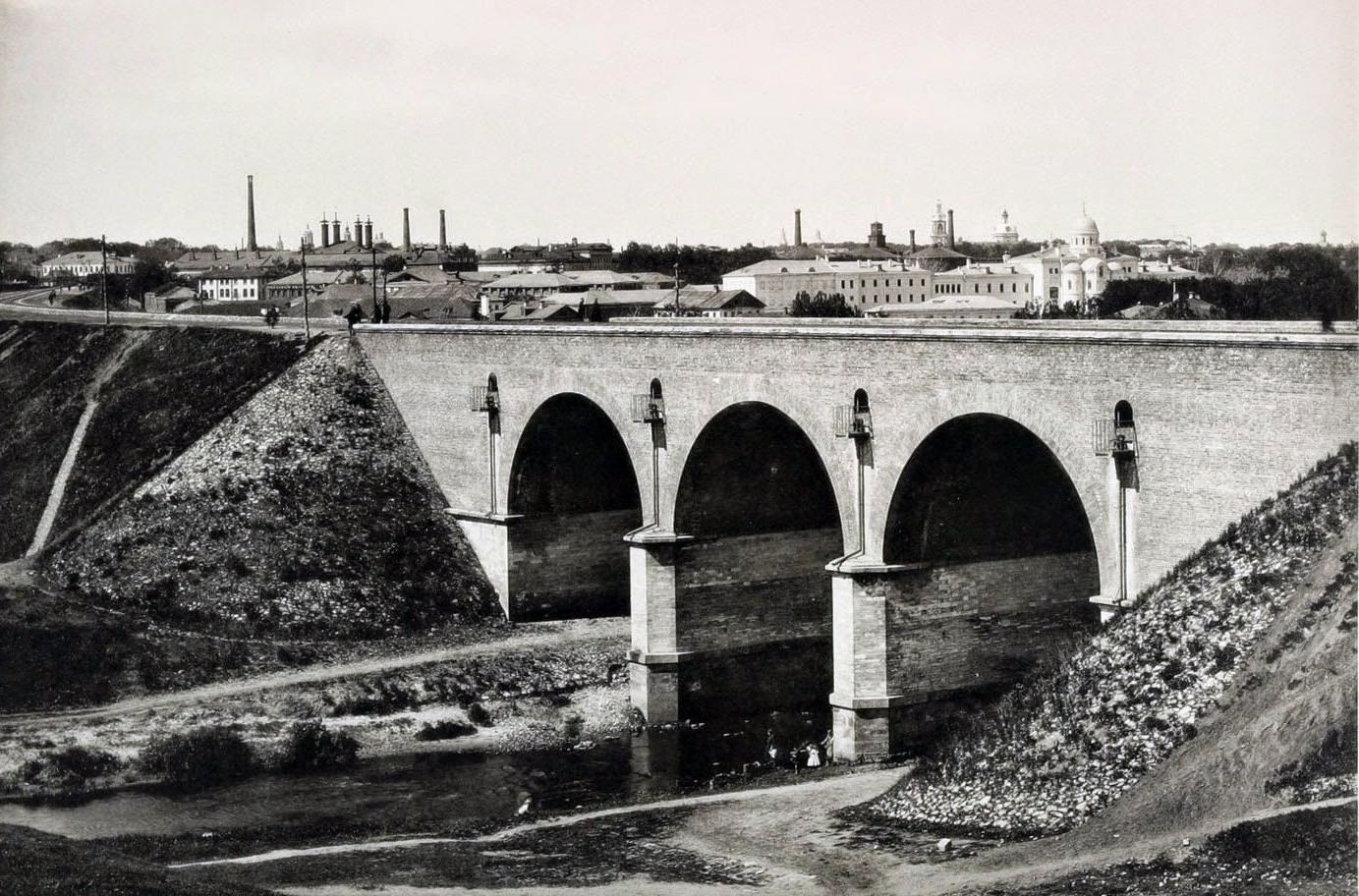

Horse-drawn trams began operating in 1882, running on rails through main streets. A ride cost 5 kopecks, affordable for middle-class residents but expensive for workers. Private carriages remained the preferred transport for wealthy families, who employed coachmen and maintained stables.

The Nicholas Railway connected Moscow to St. Petersburg in eight hours. Second-class carriages carried merchants and officials, while third-class wagons packed peasants traveling to find work. Steam locomotives pulled 20-car trains at 30 miles per hour.

Within the city, izvozchiki (cab drivers) waited at designated stands. They charged by distance and haggled over fares. Winter brought sleighs that glided over packed snow, their bells warning pedestrians to step aside.

Social Divisions

Moscow society divided into strict estates. Nobles held government positions and owned country estates. They spoke French at home and sent children to exclusive schools. The Nobility Assembly hosted balls where young women debuted in society.

Merchants formed guilds based on wealth. First-guild merchants traded internationally and served on city councils. They built Orthodox churches as displays of piety and status. Their sons attended commercial schools to learn accounting and foreign languages.

Meshchane (petty bourgeoisie) included shopkeepers, clerks, and skilled workers. They lived in rented apartments and struggled to maintain respectability. Education offered the only path to advancement for their children.

Peasants flooded into Moscow seeking factory work. They retained village ties, returning home for harvests. Many lived in artels—communal groups that shared expenses and looked after sick members.

Daily Routines

Moscow woke before dawn. Bakers fired ovens at 3 AM to produce fresh bread. Milk vendors led cows through streets, selling fresh milk door-to-door. Dvorniki (yard keepers) swept courtyards and hauled water from wells.

Breakfast consisted of tea, black bread, and porridge. Wealthy families added eggs, cheese, and cold meats. Samovars bubbled in every home, providing hot water throughout the day.

Lunch breaks lasted two hours. Workers ate in taverns serving shchi (cabbage soup) and kasha (buckwheat porridge). Office clerks brought food from home, eating at their desks.

Evenings brought different activities by class. Workers returned to crowded lodgings, while merchants attended the opera or theater. Taverns filled with men drinking vodka and playing cards.

Cultural Activities

The Bolshoi Theatre presented Italian operas and French ballets to packed audiences. Box seats cost 25 rubles, a month’s wage for workers. The Maly Theatre specialized in Russian dramas, staging plays by Alexander Ostrovsky about merchant life.

Moscow University enrolled 4,000 students in five faculties. Lectures covered law, medicine, mathematics, history, and languages. Student uniforms identified their faculty—blue for law, green for medicine. Political discussions led to periodic closures by authorities.

Publishing houses printed newspapers, journals, and books. The Moscow Gazette supported government policies, while other publications pushed boundaries of censorship. Bookshops clustered near the university, selling Russian classics and translated European novels.

Religious Life

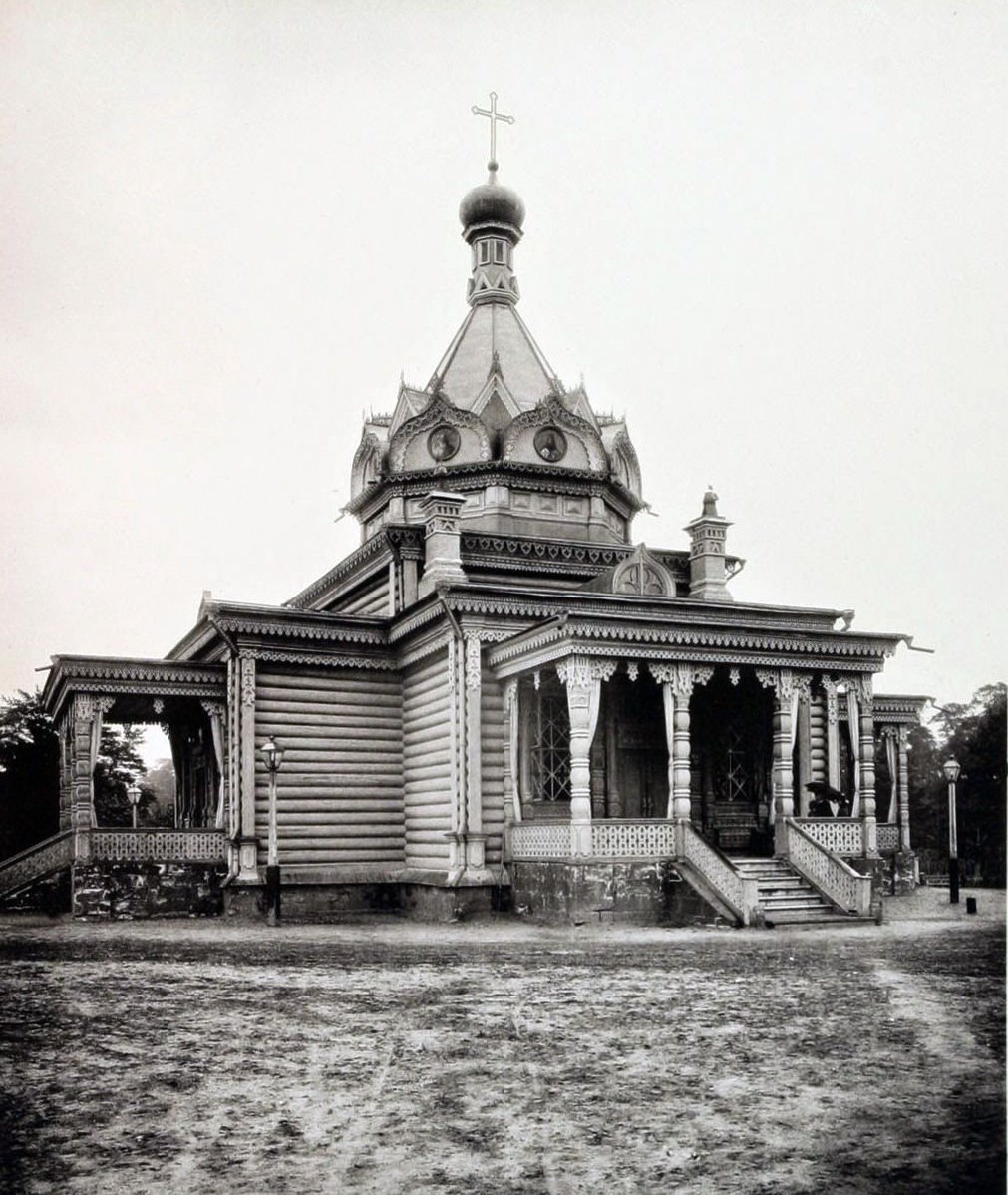

Orthodox Christianity dominated Moscow’s spiritual landscape. Church bells rang throughout the day, calling faithful to services. Major cathedrals like the Cathedral of Christ the Savior (completed in 1883) demonstrated Russia’s devotion.

Religious holidays structured the calendar. Easter brought midnight services and feasts ending the Lenten fast. Priests blessed homes during Epiphany, sprinkling holy water in every room. Icons hung in bedroom corners, with oil lamps burning before them.

Old Believers maintained separate communities, following pre-reform Orthodox practices. They operated successful businesses but faced legal restrictions. Their churches stood in remote neighborhoods, plain buildings without bell towers.

Health and Sanitation

Moscow lacked modern sewers and clean water systems. Residents drew water from the Moskva River or wells, both contaminated by waste. Typhoid and cholera struck regularly, killing thousands.

The 1883 cholera epidemic forced authorities to act. They established isolation hospitals and began planning water treatment facilities. Doctors promoted boiling water, but many ignored this advice.

Private physicians served wealthy patients in their homes. City hospitals treated poor residents in crowded wards. Medical students at Moscow University gained experience treating charity cases.

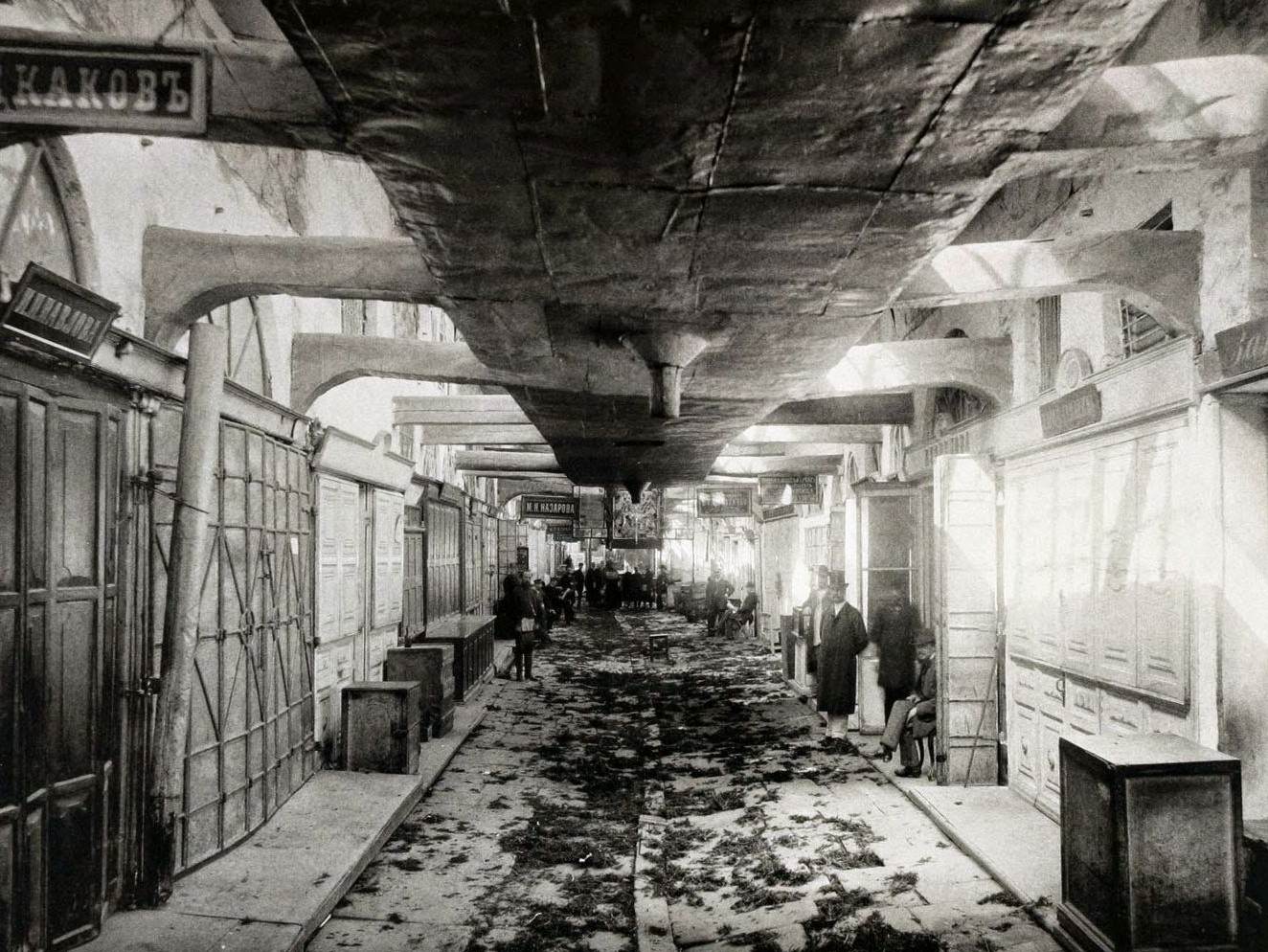

Crime and Policing

The Moscow police force numbered 3,000 men divided into districts. They wore dark green uniforms and carried sabers. Night watchmen supplemented regular patrols, calling out the hours and checking locks.

Khitrov Market gained notoriety as Moscow’s criminal quarter. Thieves, beggars, and prostitutes lived in doss-houses charging 5 kopecks per night. Police rarely entered except in large groups.

The Okhrana (secret police) monitored political activities. They recruited informers from all social classes, creating networks that reported suspicious behavior. Arrests occurred quietly, with suspects disappearing to Siberian exile.

Seasonal Rhythms

Moscow winters lasted from November to March. Temperatures dropped to -20°C, freezing the river solid. Double windows kept homes warm, with space between panes filled with salt to prevent frosting. Fur coats, felt boots, and sheepskin hats provided essential protection.

Spring brought mud season when melting snow turned streets into quagmires. Wooden planks created walkways over the worst sections. The Easter market in Red Square celebrated winter’s end with painted eggs and sweet breads.

Summer heat drove wealthy families to dachas outside the city. Those remaining sought relief in public gardens or along the river. Mosquitoes plagued everyone, leading to smoky fires in courtyards.

Autumn harvests filled markets with mushrooms, berries, and preserves. Housewives pickled cabbage and cucumbers for winter storage. Students returned to schools and universities as social season began.

Food and Dining

Moscow cuisine mixed Russian traditions with foreign influences. Restaurants near the Kremlin served French dishes to government officials. The Slavyansky Bazaar hotel restaurant became famous for its fish soup and sterlet.

Traktirs (taverns) catered to different classes. Simple establishments offered tea, vodka, and basic foods. Fancier versions provided private rooms for merchant negotiations. All featured loud conversations and tobacco smoke.

Traditional foods remained popular. Blini appeared during Maslenitsa (Butter Week) before Lent. Kulich (sweet Easter bread) and paskha (cheese dessert) marked Easter celebrations. Winter meant preserved foods—sauerkraut, pickled mushrooms, and salted fish.

Education Expands

Primary schools increased throughout the decade. The city government opened schools in each district, teaching reading, arithmetic, and religion. Boys and girls attended separate classes. Teachers earned modest salaries but held respected positions.

Gymnasiums prepared students for university. Classical gymnasiums emphasized Greek and Latin, while real gymnasiums focused on modern languages and sciences. Tuition fees excluded most working-class children.

Technical schools trained engineers and mechanics for new industries. The Moscow Technical School produced graduates who designed factories and railroads. Evening classes allowed workers to gain basic literacy.

Entertainment and Leisure

Pleasure gardens offered weekend escapes. The Hermitage Garden featured outdoor theaters, restaurants, and walking paths. Orchestras played waltzes while couples strolled under gas lamps. Admission cost 30 kopecks, limiting access to the middle class.

Circus performances drew all social classes. Trained horses, acrobats, and clowns performed under canvas tents. The Nikitin Circus established a permanent building, presenting shows year-round.

Bath houses served as social centers. The Sandunovsky Baths offered luxury facilities with marble pools and steam rooms. Neighborhood baths provided basic washing facilities where workers gathered weekly. Business deals and gossip flowed freely in the steam.