Alphonse Gabriel Capone was born in Brooklyn, New York, on January 17, 1899, to Italian immigrants Gabriele and Teresina Capone. Growing up in a crowded tenement, he was part of a large family with eight siblings. As a youth, he showed academic promise but dropped out of school in the sixth grade after a physical altercation with a teacher. His life soon turned from the classroom to the streets, where he became involved with local street gangs like the Junior Forty Thieves and the Bowery Boys.

His most significant association was with the powerful Five Points Gang, led by Frankie Yale. Working in Yale’s headquarters, a Coney Island saloon and dance hall called the Harvard Inn, Capone served as a bouncer and bartender. It was here that he acquired the scars that would lead to his famous nickname, “Scarface.” One evening, he made an offensive comment to a woman, and her brother, Frank Galluccio, slashed Capone’s face with a knife, leaving three distinct scars on his left cheek. Capone disliked the nickname and would often try to hide the scars from photographers or claim they were war wounds.

In New York, Capone also fell under the mentorship of Johnny Torrio, an influential racketeer. When Torrio moved to Chicago to build a criminal empire, he soon sent for his protégé. In 1920, Capone left New York for Chicago, officially to work as a bouncer in a brothel, but in reality, to become a key lieutenant in Torrio’s expanding organization.

Read more

The Chicago Outfit

The timing of Capone’s arrival in Chicago was perfect for an aspiring gangster. In January 1920, the 18th Amendment was enacted, making the production, sale, and transport of alcoholic beverages illegal in the United States. This era, known as Prohibition, created a massive black market for alcohol, and Johnny Torrio intended to dominate it. Capone quickly proved his value, managing the bootlegging, gambling, and prostitution rackets that formed the core of Torrio’s business.

In 1925, after a near-fatal assassination attempt by rival North Side Gang members, a shaken Johnny Torrio decided to retire. He handed complete control of his vast criminal enterprise, which would become known as the Chicago Outfit, to the 26-year-old Al Capone. Under Capone’s leadership, the organization’s reach and profits soared. At its peak, his empire was estimated to generate as much as $100 million a year, an astronomical sum for the time. This money came from illegal breweries, speakeasies, bookmaking joints, brothels, and distilleries.

Capone ran his operations like a modern corporation. He used violence and intimidation to eliminate rivals and secure territory, but he also used bribery to corrupt the city’s political machine. Police officers, judges, and city officials, including Mayor William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson, were on his payroll. This systematic corruption provided a shield of protection that made him seem untouchable.

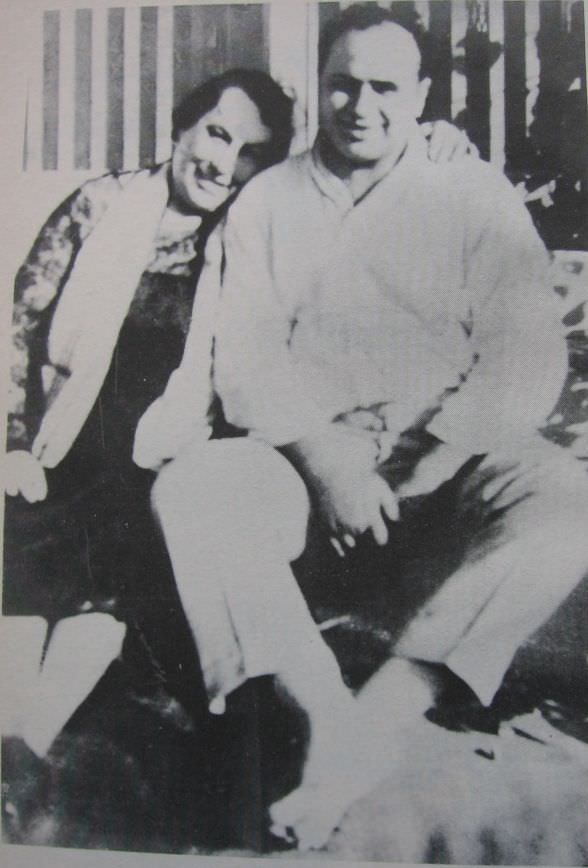

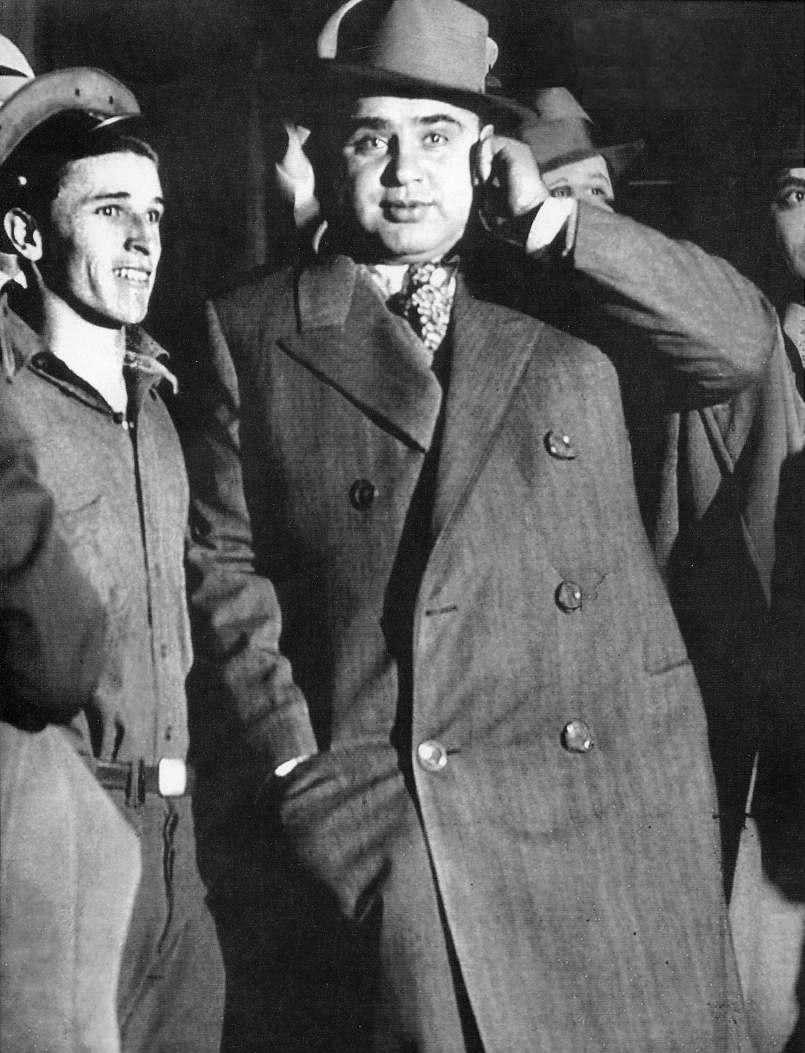

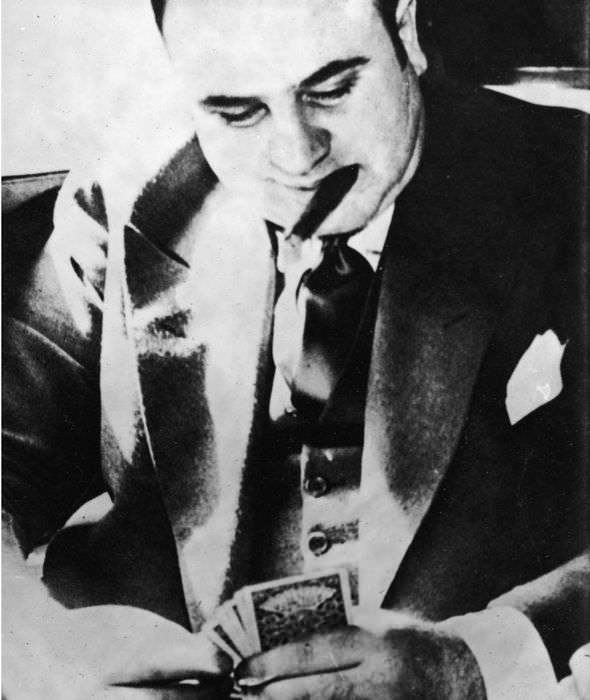

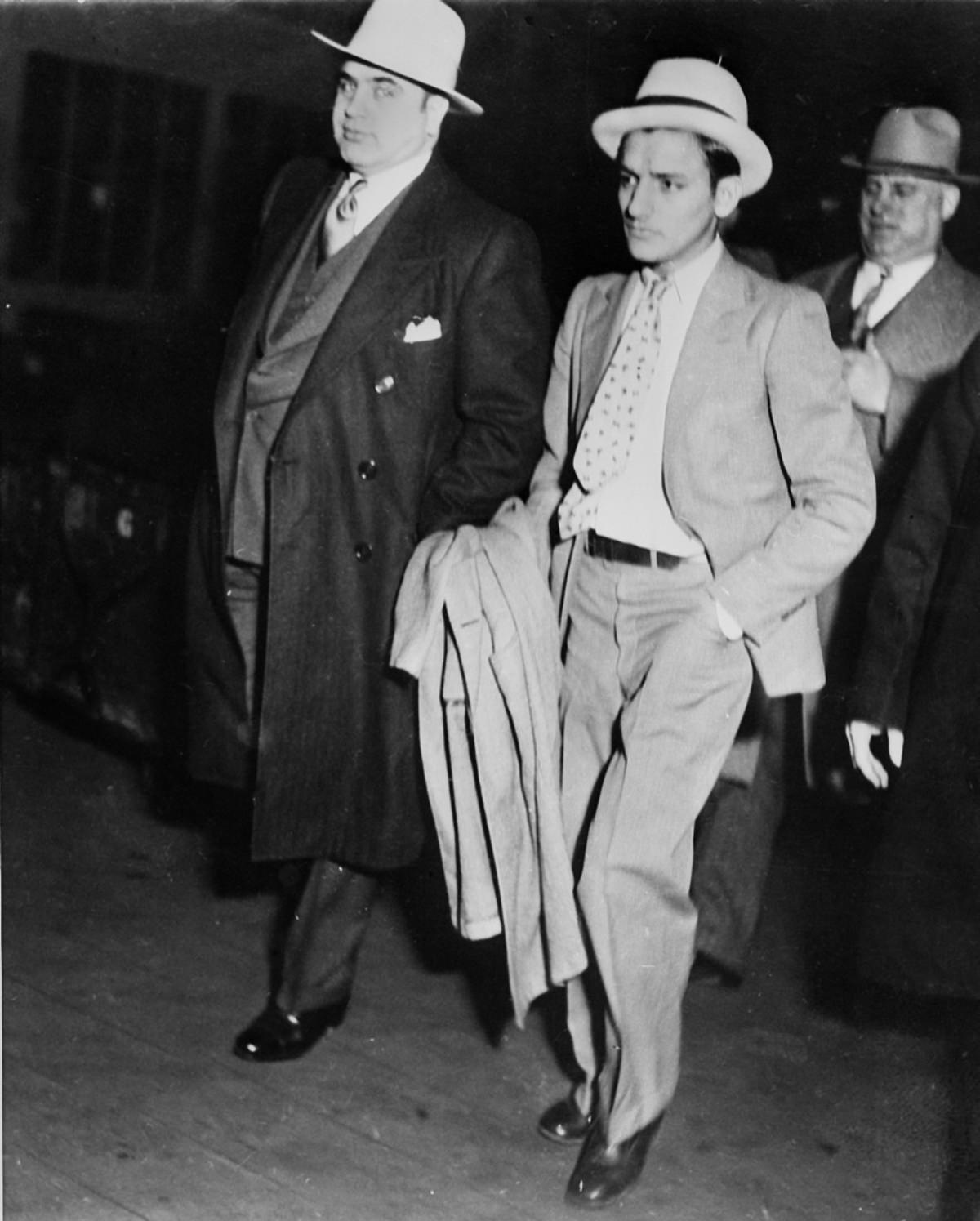

He cultivated a unique public image. Unlike mobsters who operated entirely in the shadows, Capone lived a lavish and public life. He wore expensive, custom-tailored suits, diamond jewelry, and was often seen at sporting events and the opera. He established his headquarters at the Lexington Hotel in downtown Chicago, where he occupied a multi-room suite. He spoke openly with newspaper reporters, presenting himself as a simple businessman providing the public with goods and services they desired. During the Great Depression, he funded a soup kitchen that provided free meals to Chicago’s unemployed, an act of public relations designed to win favor with the common people.

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre

The immense profits of the bootlegging trade led to violent turf wars with rival gangs. Capone’s main adversary was George “Bugs” Moran, leader of the North Side Gang. Their conflict reached its brutal climax on February 14, 1929, in an event that became known as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

On that morning, seven men associated with the Moran gang were gathered inside a garage on North Clark Street. Four assassins, two of them dressed as police officers, entered the building under the pretense of a raid. They lined the seven men up against a wall and opened fire with Thompson submachine guns and a shotgun, firing more than 70 rounds. All seven men were killed. Capone, who was conveniently at his home in Florida at the time, was widely believed to have ordered the hit, although he was never officially charged.

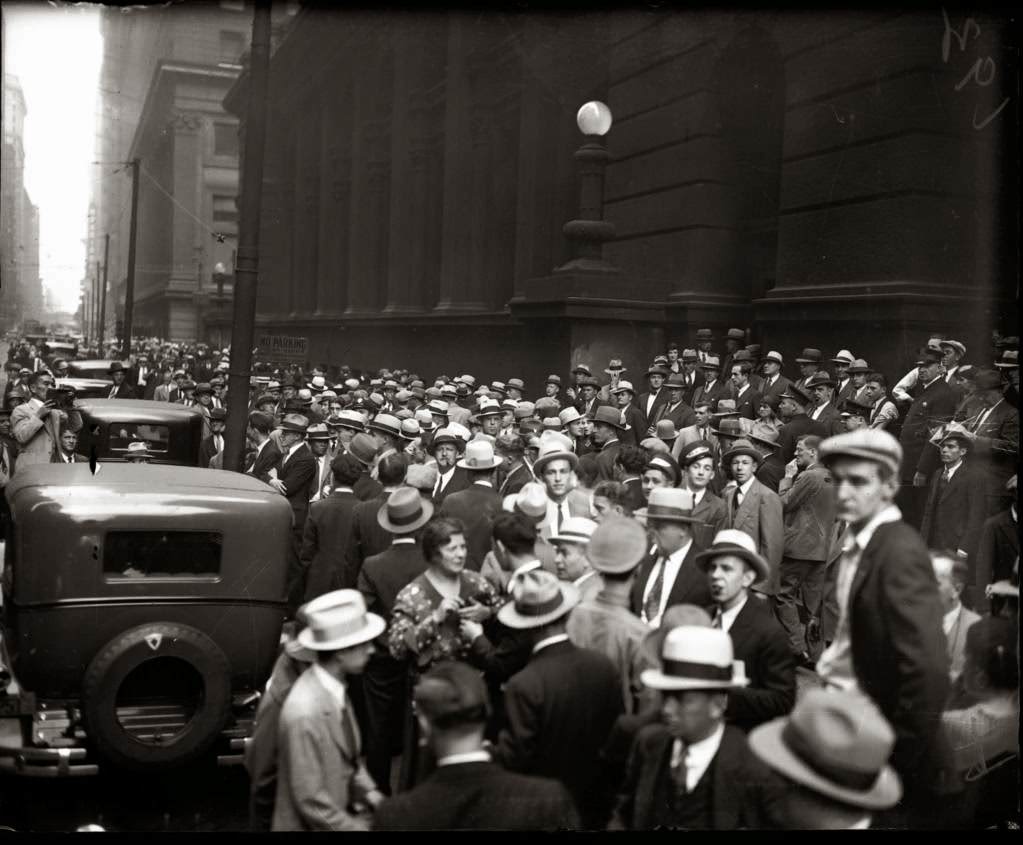

The massacre was a strategic success for Capone, as it eliminated key members of Moran’s crew and solidified his control over the city’s underworld. However, the shocking brutality of the crime, detailed in newspapers across the country, turned public opinion against him. He was no longer seen as a roguish local businessman but as a vicious and dangerous killer. The federal government, under pressure to act, intensified its efforts to bring him down.

The Downfall

While lawman Eliot Ness and his team of agents, nicknamed “The Untouchables,” famously targeted Capone’s illegal breweries and distilleries, their actions did more to disrupt his operations than to build a criminal case against him. The strategy that ultimately brought Capone down came from a different branch of government: the U.S. Treasury Department.

An investigation led by Special Agent Frank J. Wilson focused not on Capone’s violent crimes, but on his finances. For years, Capone had lived a life of extreme luxury without ever filing an income tax return. Wilson’s team meticulously combed through financial records, ledgers, and witness testimony to prove that Capone had a substantial income that he was hiding from the government.

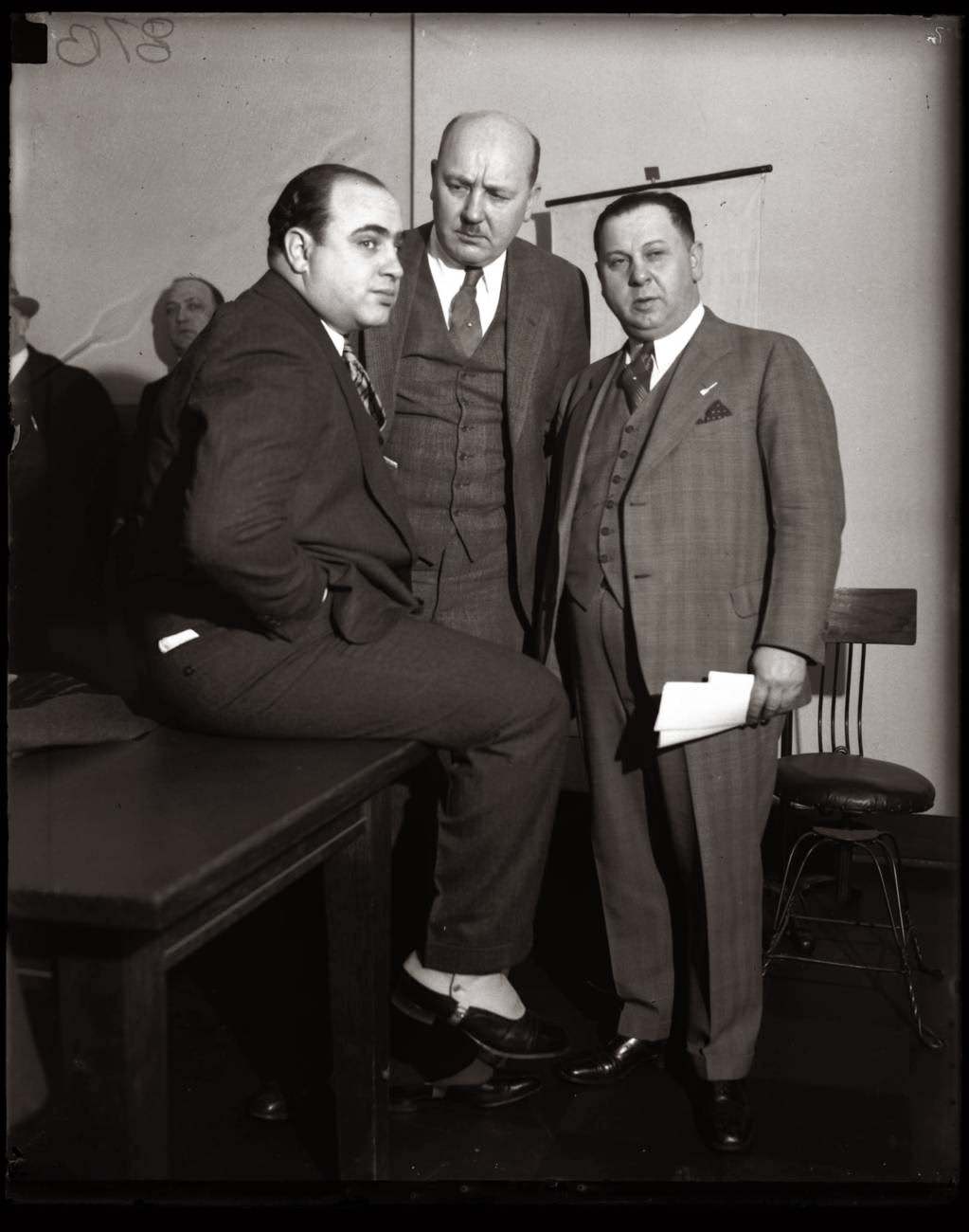

In 1931, the federal government felt it had enough evidence to secure a conviction. Capone was indicted on 22 counts of federal income tax evasion. Confident in his ability to bribe or intimidate the jury, Capone’s lawyers initially negotiated a plea deal for a short sentence. However, the presiding judge, James H. Wilkerson, refused to honor the deal. Forced to go to trial, Capone’s case seemed doomed when Judge Wilkerson swapped the entire jury pool at the last minute with one from a different trial, thwarting any attempts at jury tampering.

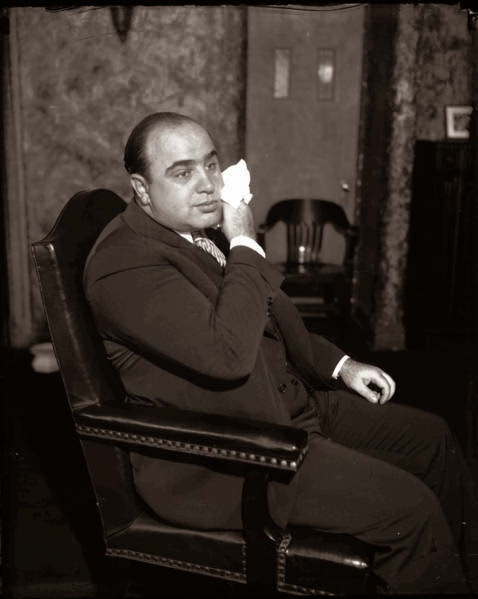

On October 17, 1931, Al Capone was found guilty on five counts of tax evasion. He was sentenced to 11 years in federal prison, fined $50,000, and ordered to pay court costs. This was the harshest sentence ever handed down for tax evasion at the time.

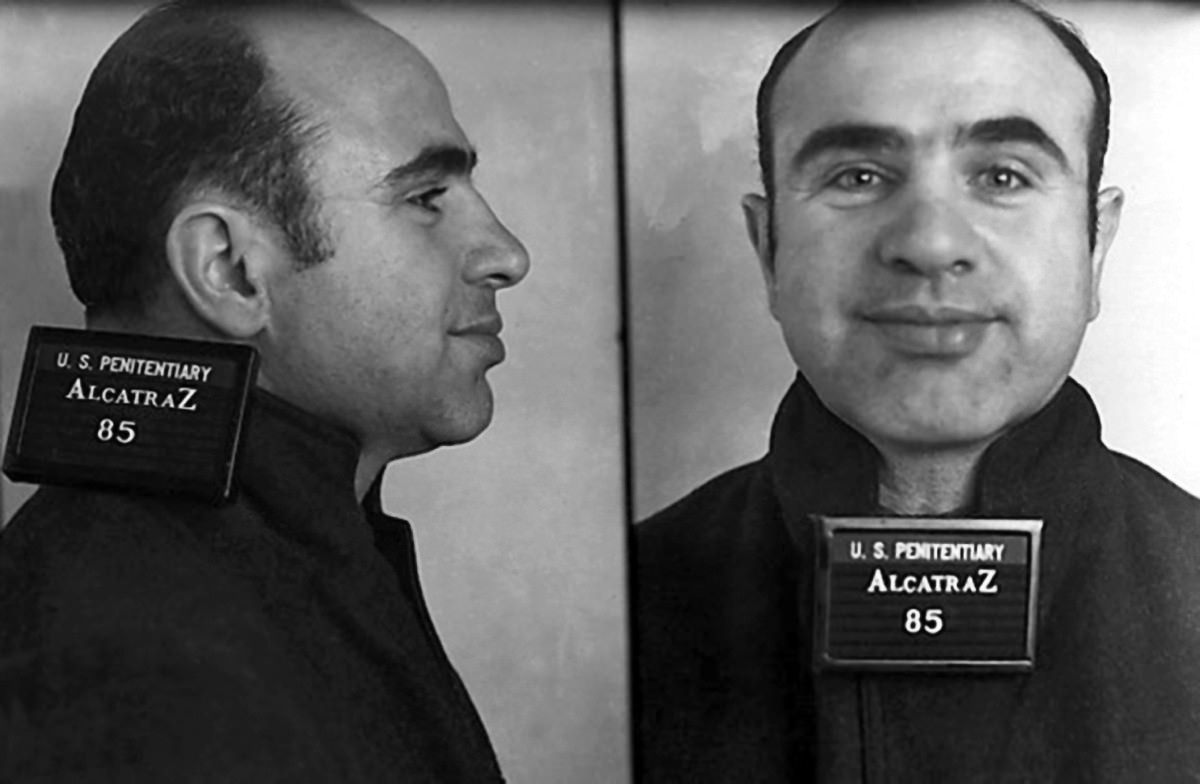

He began his sentence in 1932 at the U.S. Penitentiary in Atlanta. In 1934, he was transferred to the newly opened maximum-security federal prison on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. At Alcatraz, he was no longer a powerful boss but simply prisoner AZ-85. His health, already compromised by an untreated case of syphilis he had contracted as a young man, began to deteriorate rapidly. The disease progressed into neurosyphilis, severely affecting his cognitive functions. After being released from prison in 1939 due to his poor health, he spent his final years with his family at his mansion in Palm Island, Florida, in a state of mental decline. He died from a stroke and pneumonia on January 25, 1947, at the age of 48.