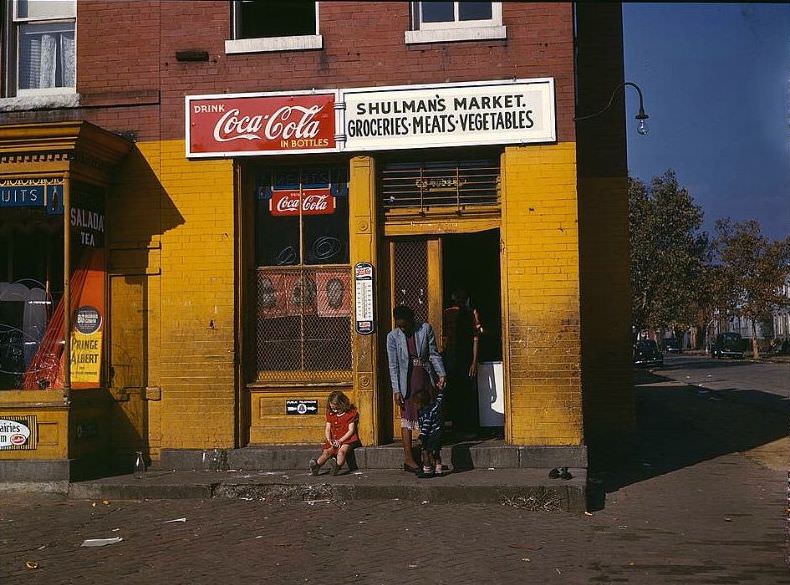

Grocery shopping in the early 1940s remained a face-to-face interaction rather than a self-service experience. A long, high wooden counter separated the customer from the merchandise. Shoppers stood in front of the counter and read their lists aloud to a clerk wearing a white apron. The clerk moved back and forth along the shelves, pulling down boxes of cereal, tins of coffee, and bags of flour. For items located on the highest shelves, they used a long wooden pole with a mechanical metal claw at the end to grip the products.

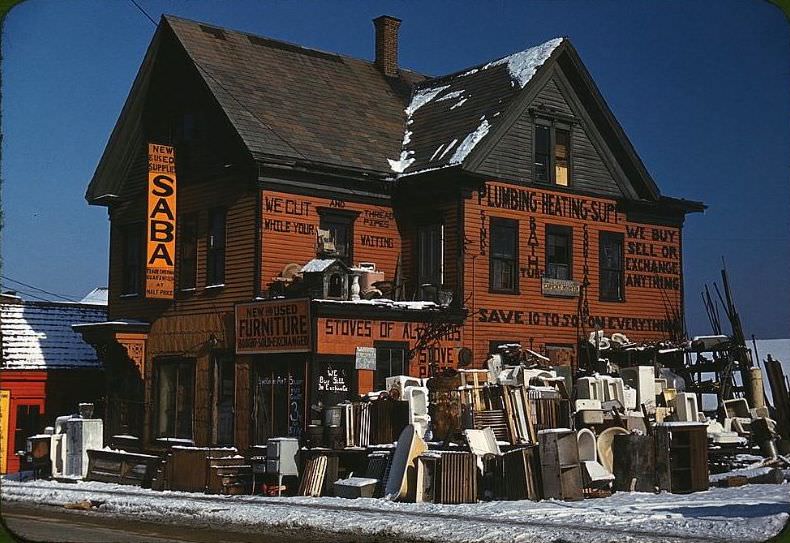

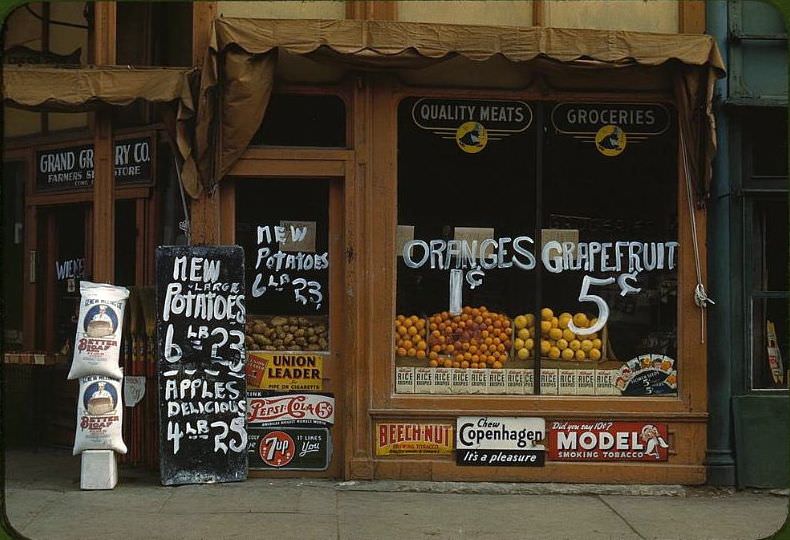

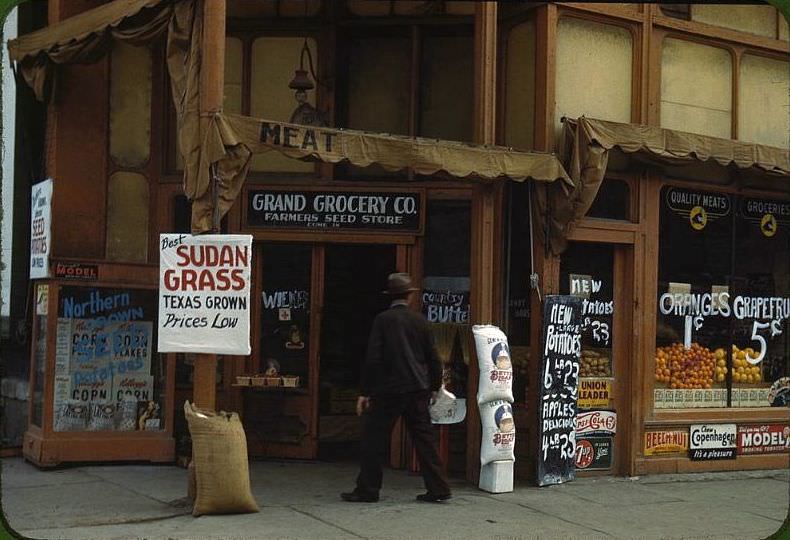

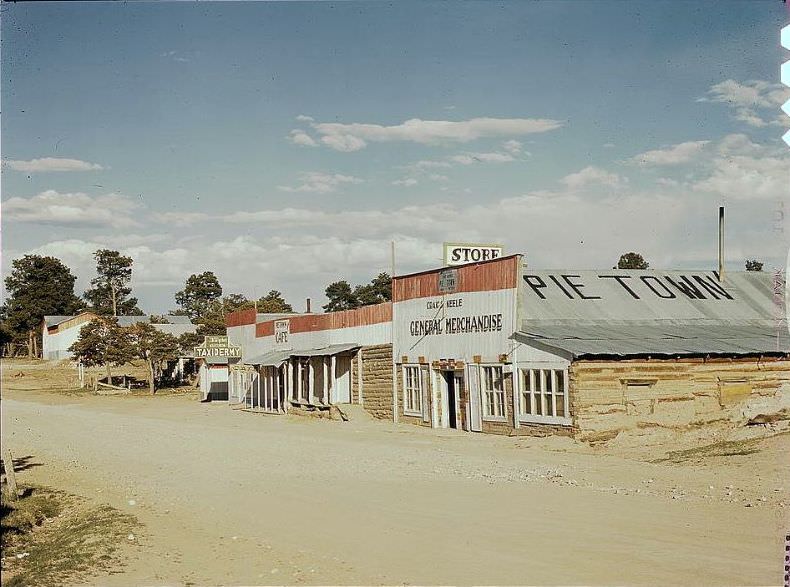

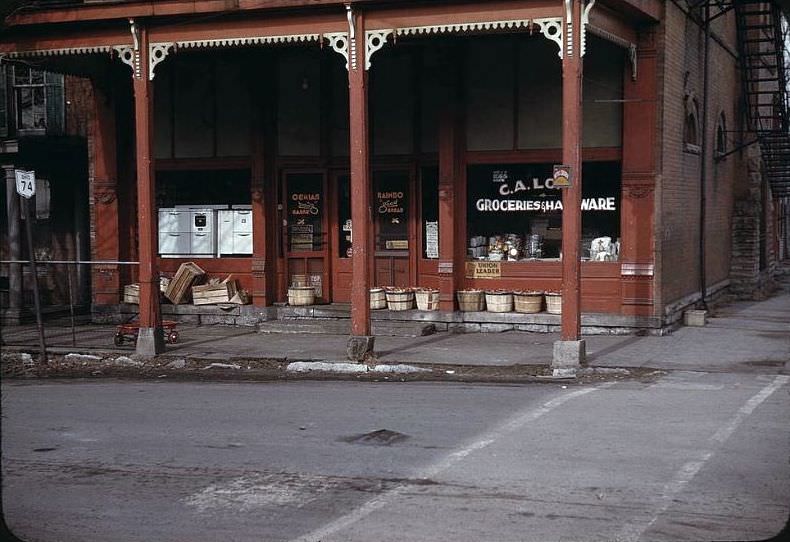

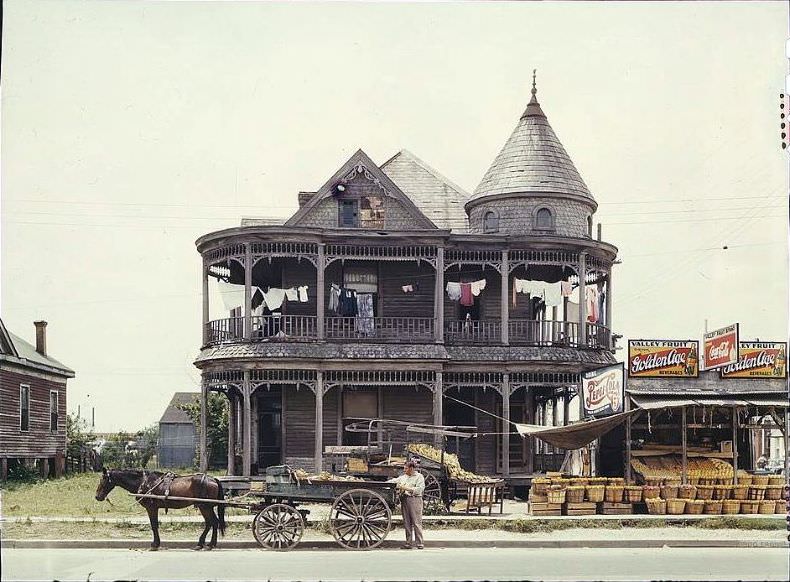

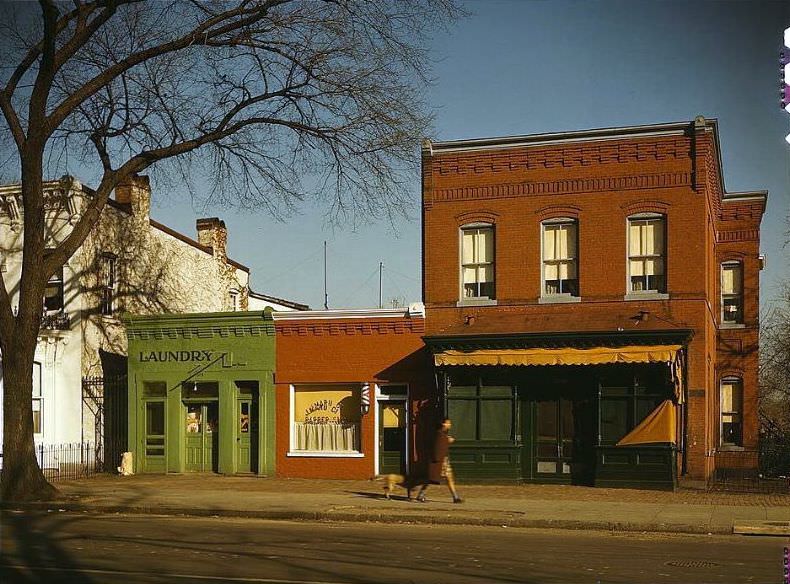

Fresh produce sat in wooden crates or bushel baskets near the front window, often under a striped awning to block the sun. Prices were written directly on the glass window in grease pencil or displayed on small, hand-painted cardboard signs. A large, white porcelain scale dominated the counter. The grocer weighed apples, potatoes, and onions individually, calculating the price by hand on a paper pad. Most goods, like beans or rice, were not pre-packaged but were scooped from bulk burlap sacks into brown paper bags.

The Butcher’s Domain

The meat counter operated as a distinct section within the store, often smelling of raw beef and sawdust. The floor was covered in a thick layer of fresh sawdust to absorb blood and scraps, which was swept out at the end of every day. Whole hams, sides of bacon, and long strings of encased sausages hung from metal hooks on the ceiling. Customers did not choose from pre-wrapped styrofoam trays; they pointed to a specific cut of meat in the glass case. The butcher placed the slab on a heavy wooden block, sliced it to the requested thickness with a sharp knife or a bandsaw, and wrapped it tightly in pink or brown butcher paper, securing it with white cotton string.

Read more

The Ration Book Economy

By 1942, the rules of commerce shifted dramatically due to the war effort. Cash alone was no longer sufficient to purchase food. Every man, woman, and child possessed a government-issued ration book filled with stamps. When a housewife bought a pound of sugar or a cut of steak, she had to hand over the correct specific stamps along with her money. If the stamps were gone for the month, the family went without, regardless of how much cash they had. Shopkeepers handled small red tokens made of vulcanized fiber for change for meat points and blue tokens for processed foods. Posters hung on the walls warning against waste, with slogans like “Food is a Weapon—Don’t Waste It.”

The Five-and-Dime

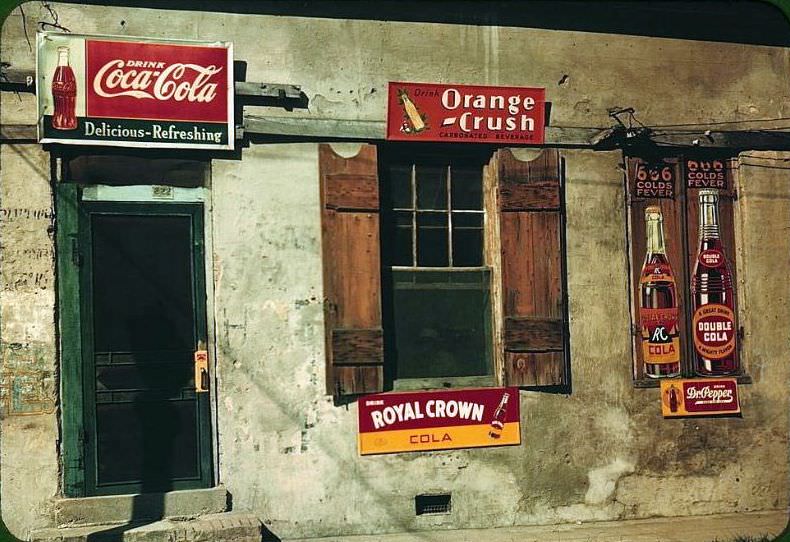

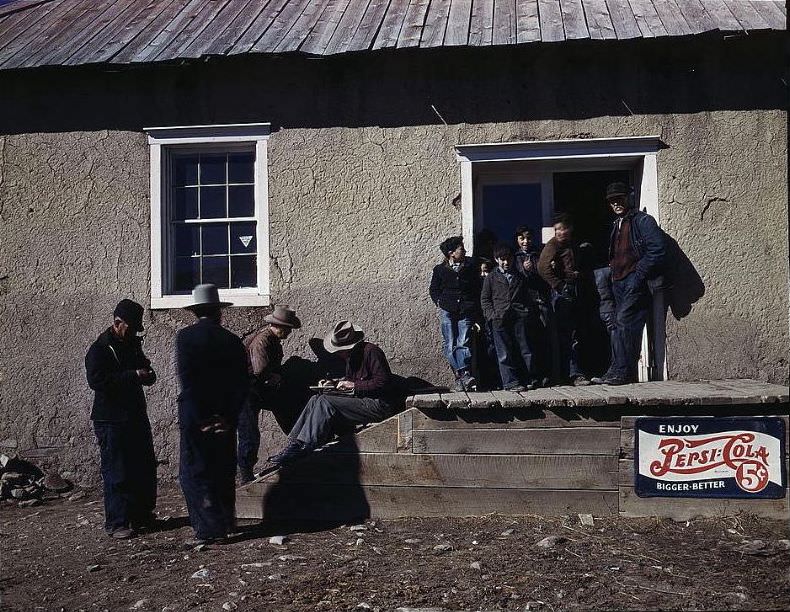

F.W. Woolworth and other “five-and-dime” variety stores dominated the main streets of American towns. These stores featured low counters divided by glass partitions, displaying thousands of small, inexpensive items. Shoppers browsed through bins filled with sewing needles, metal hairpins, tin toys, and envelopes, all costing five or ten cents. The air inside smelled of roasted nuts and popcorn, which were sold fresh from a glass case near the entrance. The lunch counter at the back of the store served as a busy social hub. Customers sat on spinning round stools bolted to the floor, eating grilled cheese sandwiches and drinking cola served in cone-shaped glasses set inside metal holders.

The Corner Drugstore

The pharmacy served a dual purpose as a medical center and a neighborhood gathering place. A marble-topped soda fountain with gleaming chrome taps lined one wall. A “soda jerk” wearing a paper hat mixed phosphates, egg creams, and malted milkshakes by hand using metal canisters. Behind the high partition at the back, the druggist compounded prescriptions manually, using a mortar and pestle to grind powders and pouring liquids into glass bottles. Rack upon rack of comic books, pulp magazines, and cigars lined the other walls, attracting teenagers who stopped by after school to read and socialize.