When the Great War erupted in 1914, the airplane was a joke. It was a fragile curiosity made of wood, wire, and cloth, prone to crashing in a light breeze. Military commanders saw it as a novelty, a toy for daredevils, not a serious weapon of war. No one could have predicted that in just four short years, these flimsy contraptions would evolve into deadly fighting machines, turning the skies above Europe into a terrifying new battlefield where young men fought and died in a completely new kind of combat.

1914: Gentlemen and Eyes in the Sky

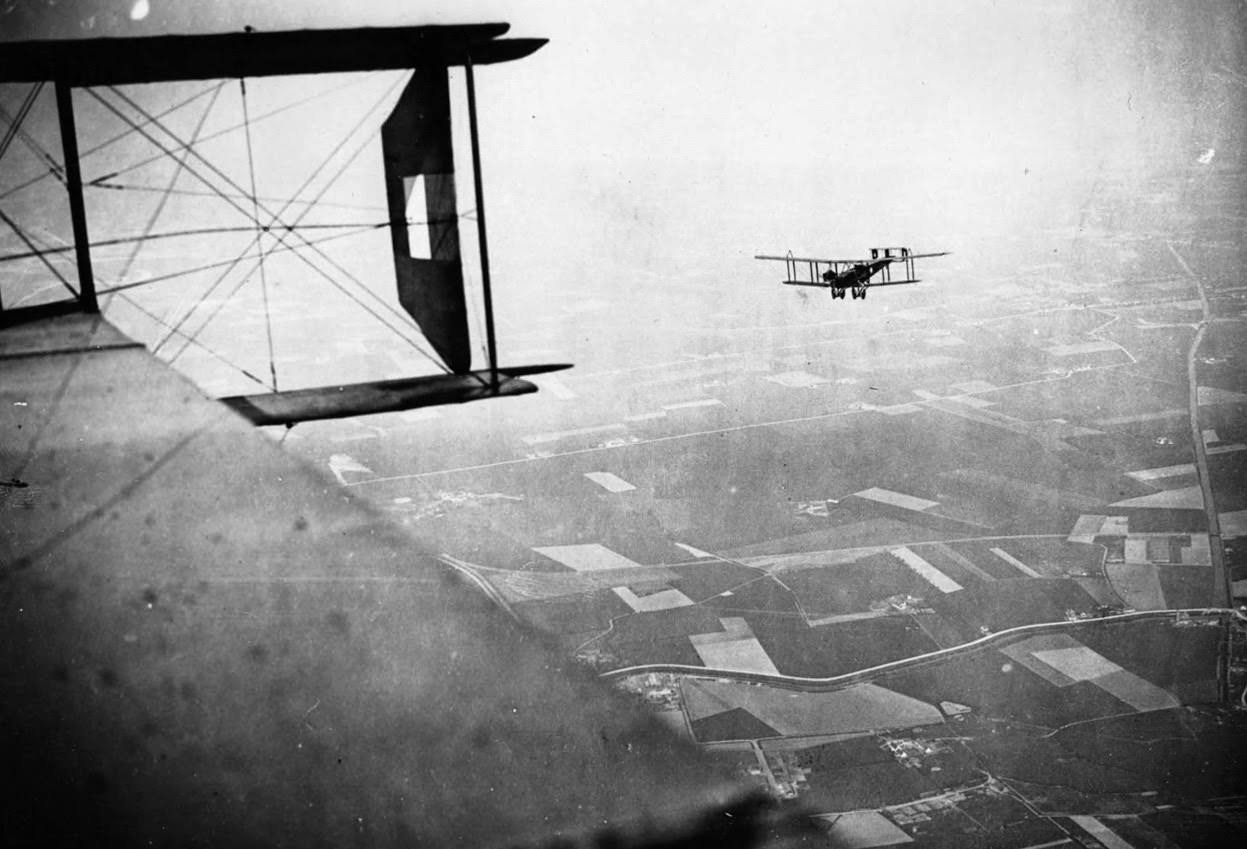

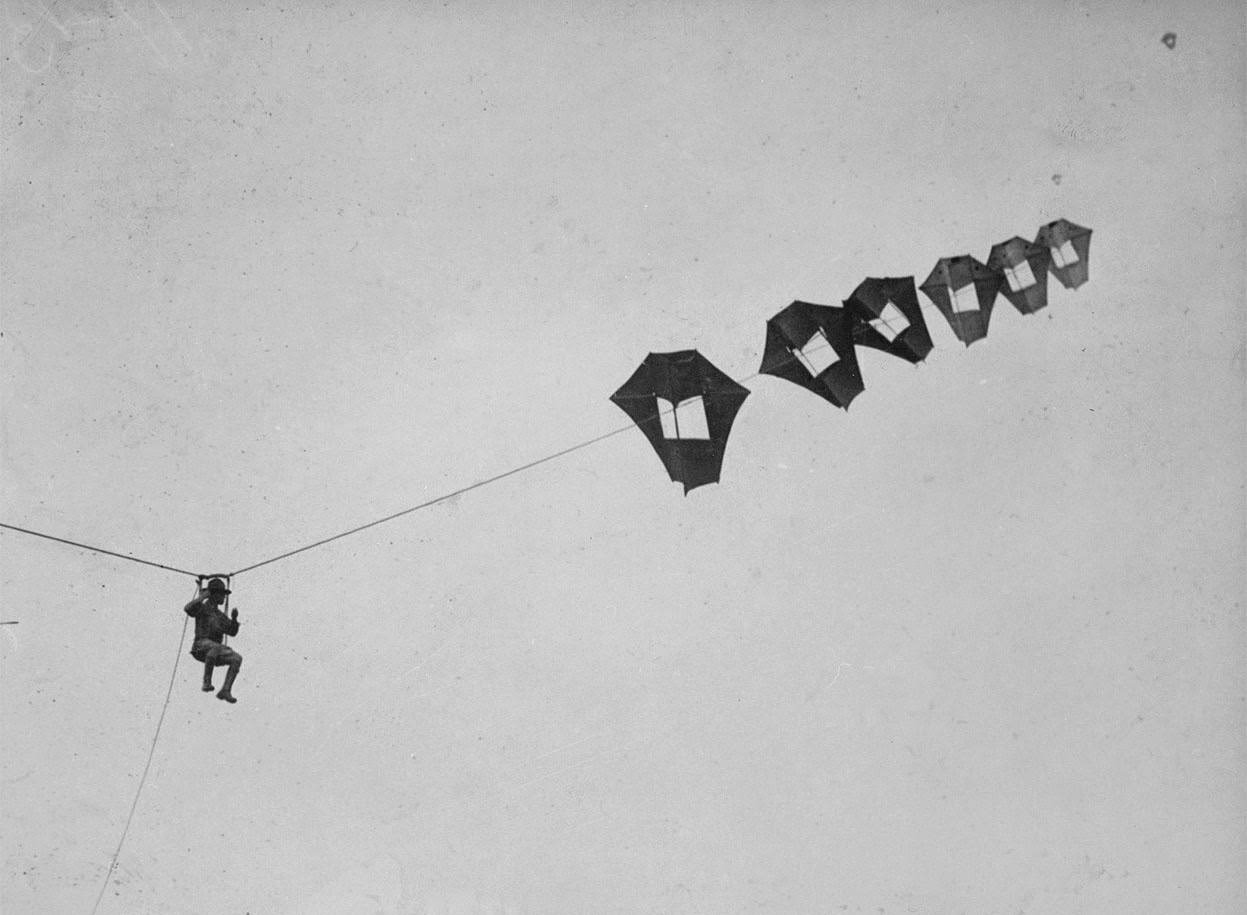

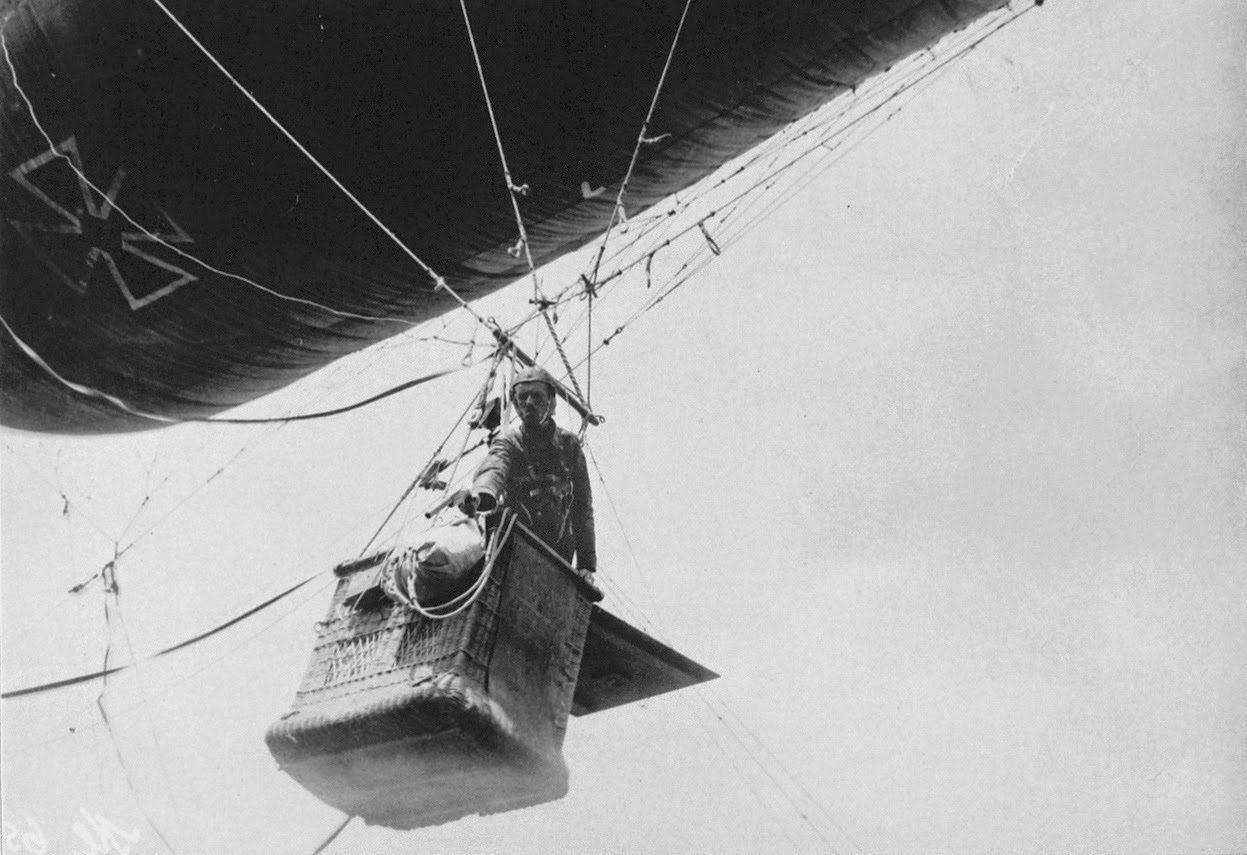

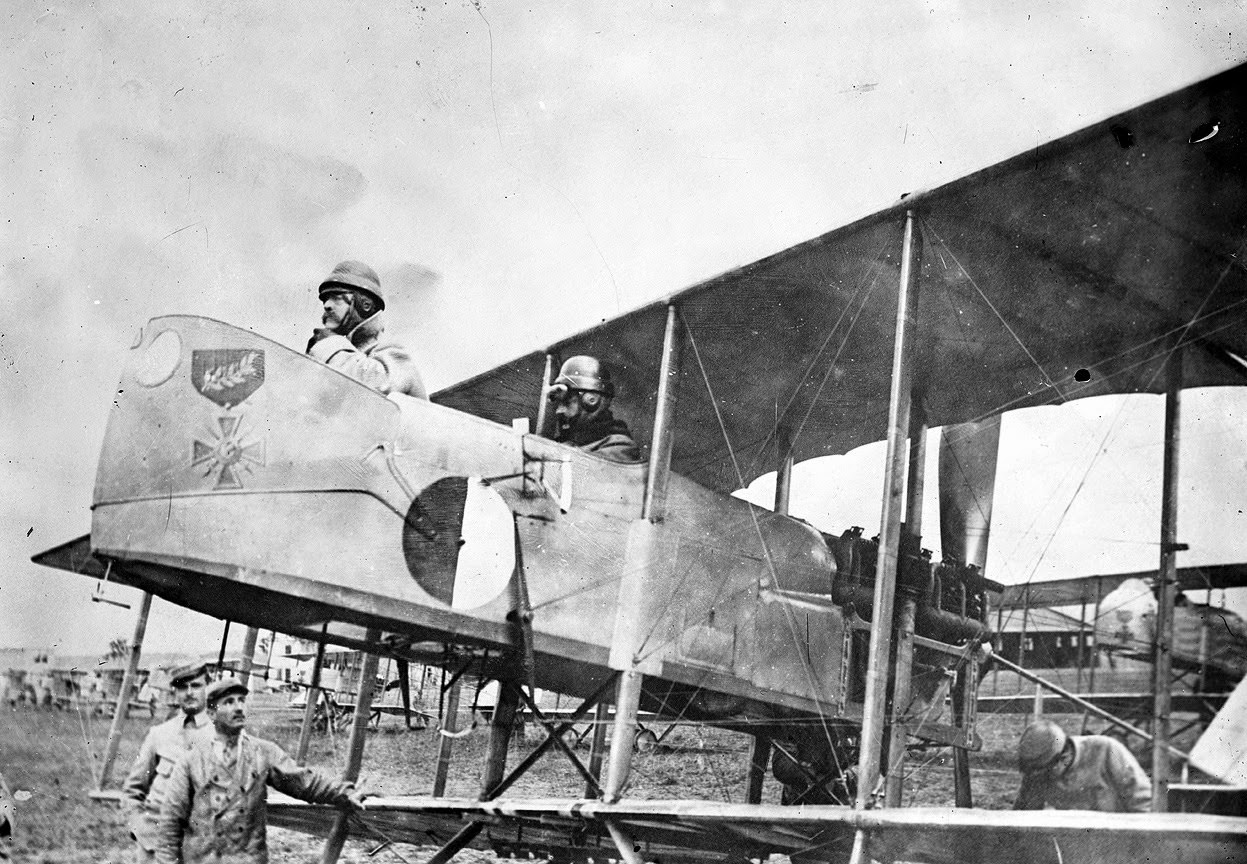

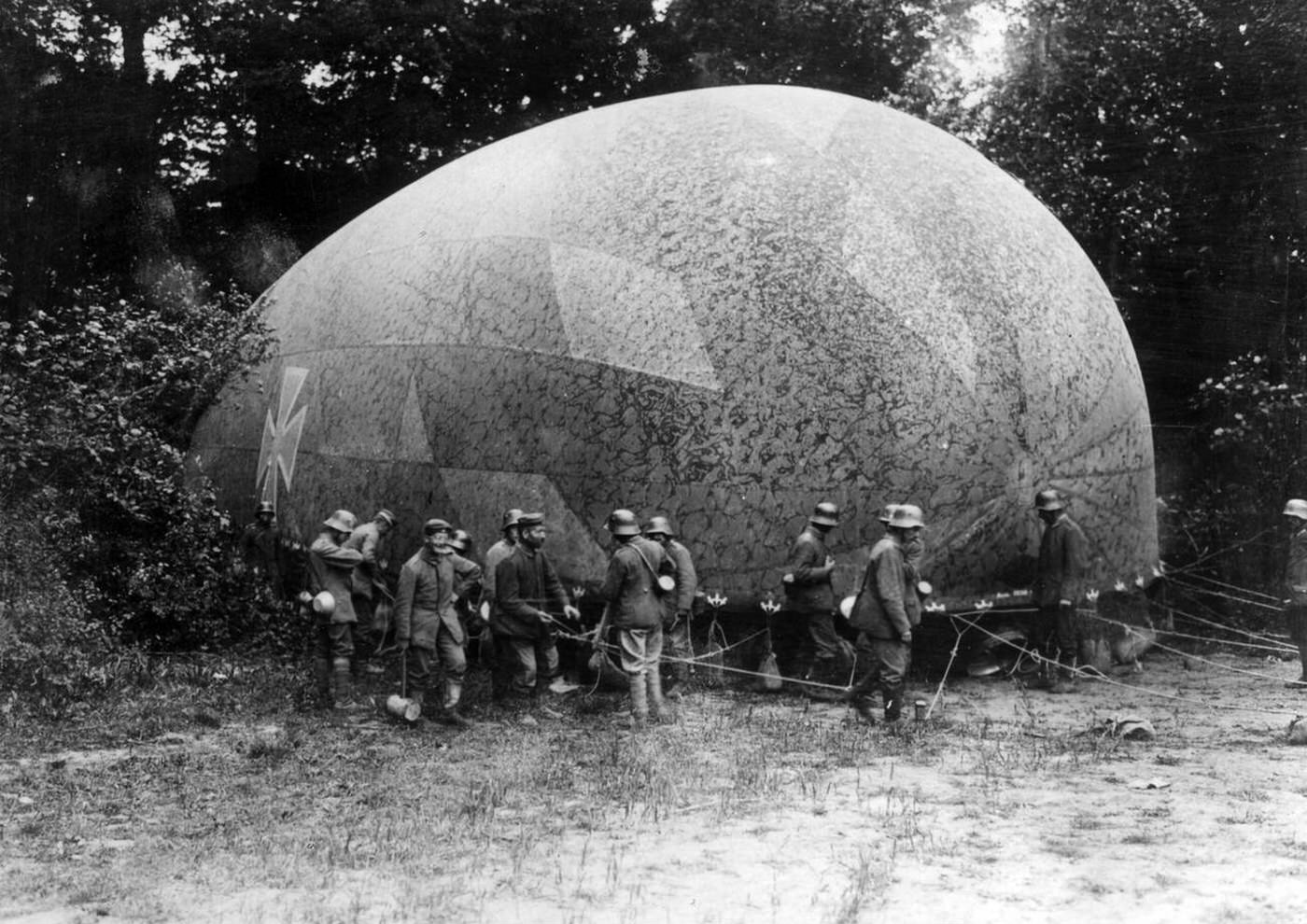

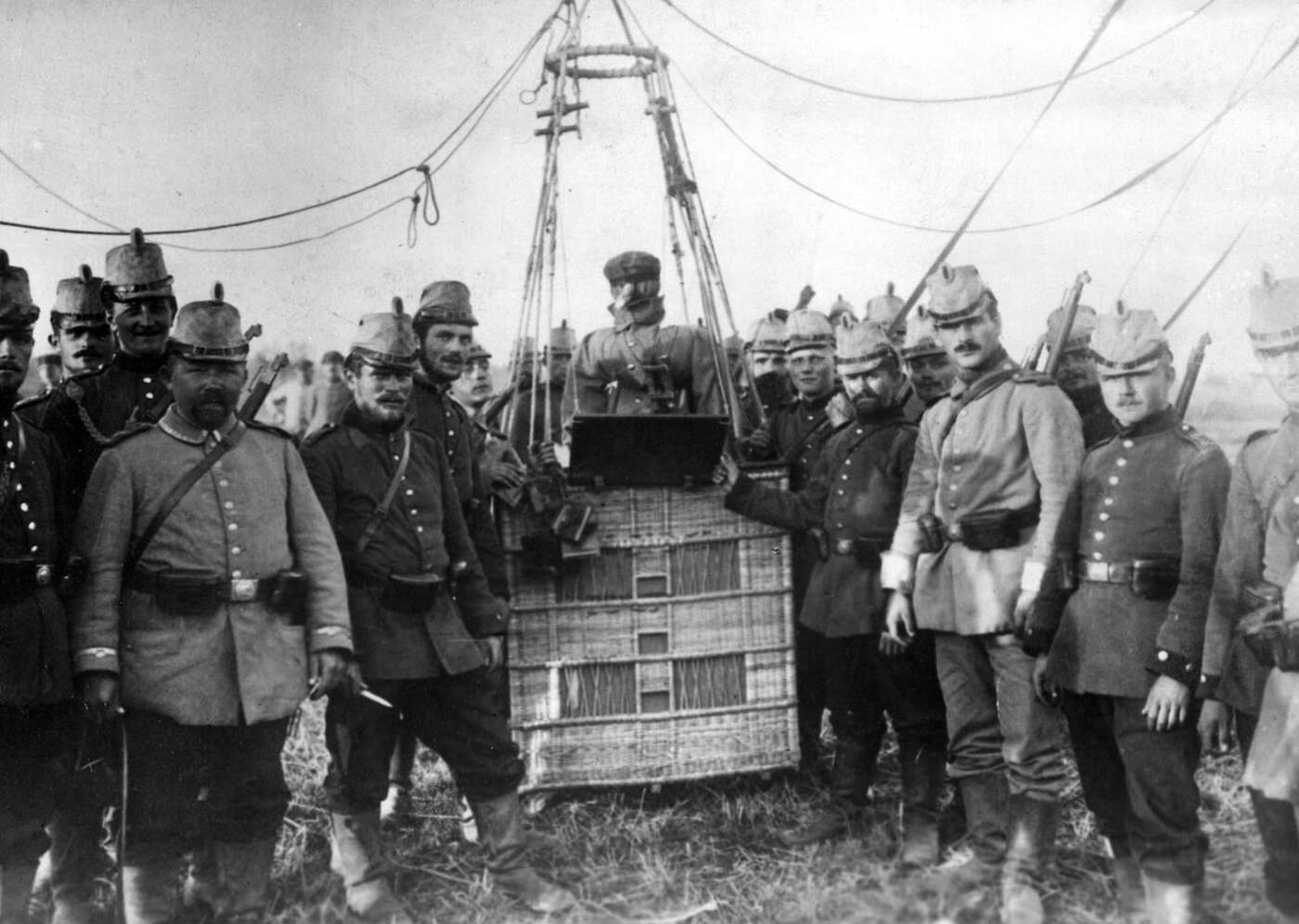

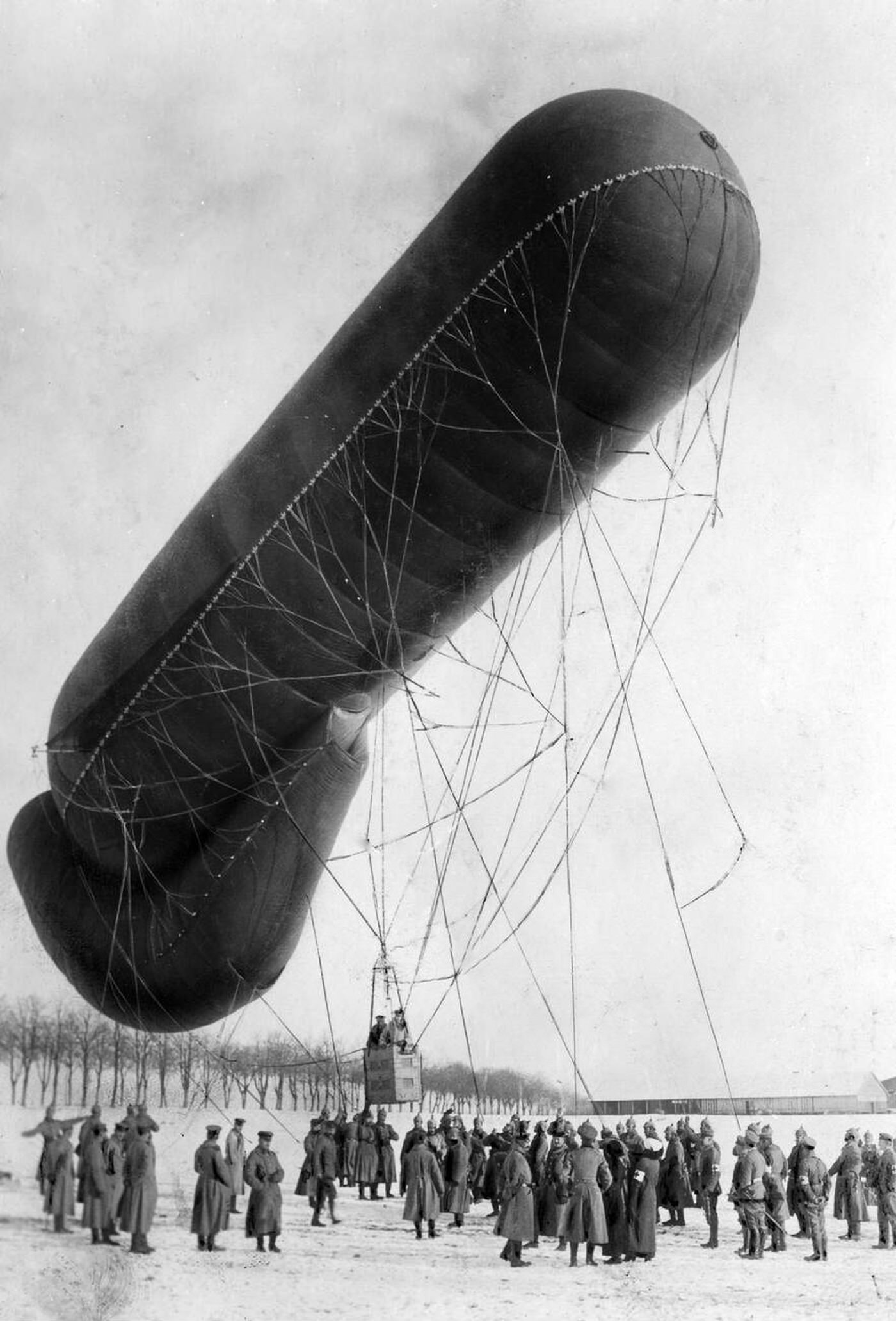

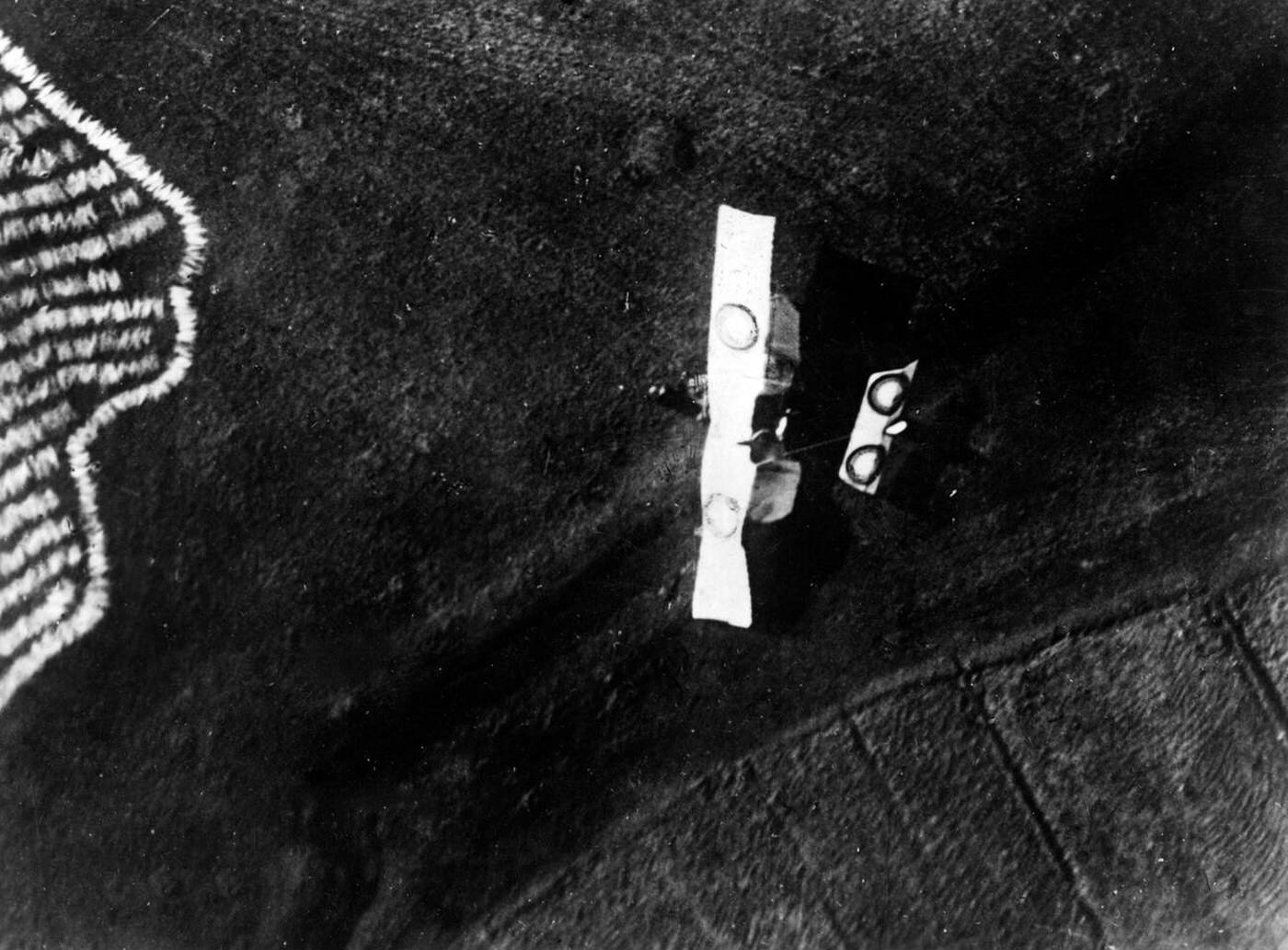

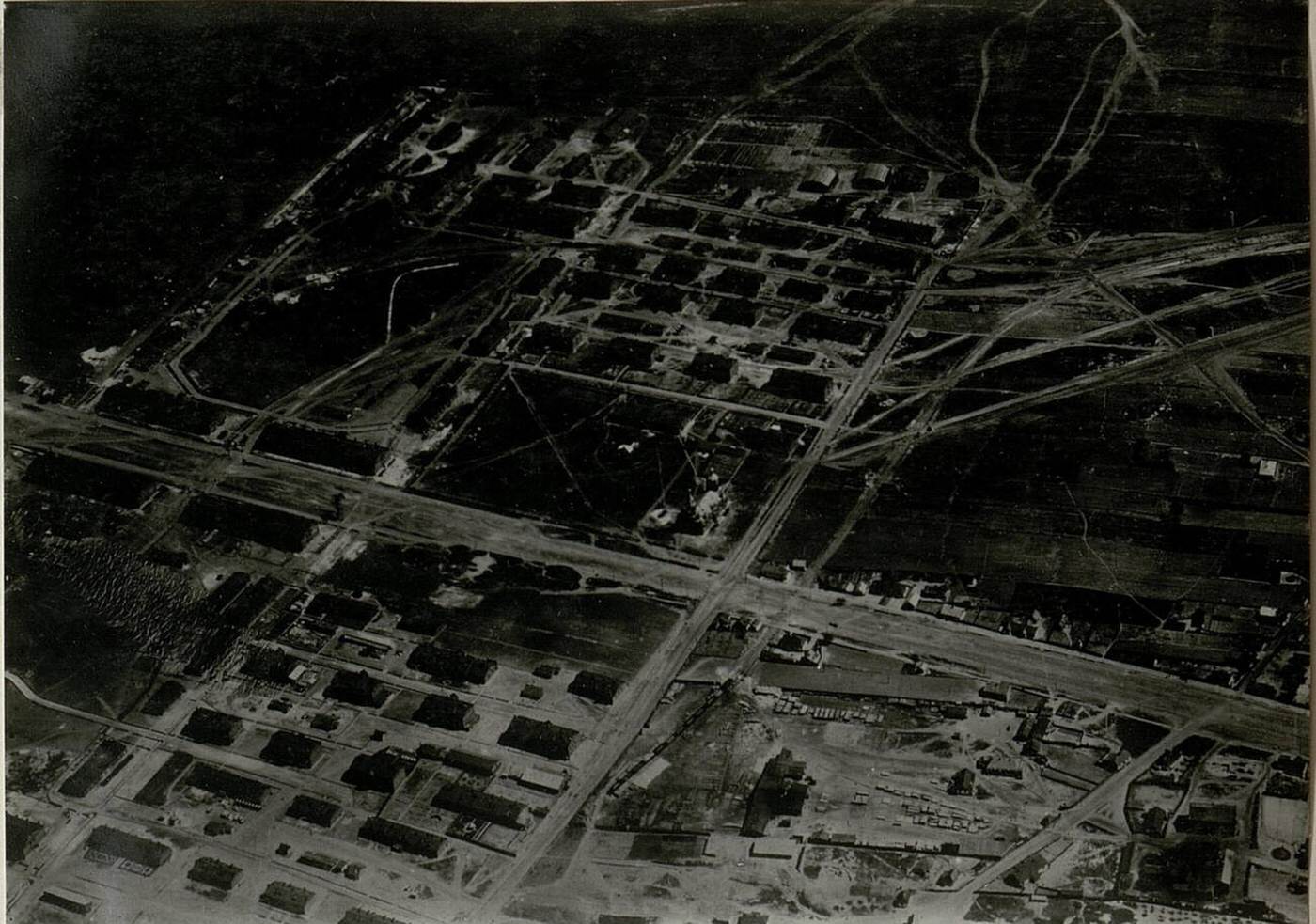

In the first months of the war, the airplane had exactly one job: reconnaissance. Generals quickly realized that a pilot flying high above the trenches could see things a cavalry scout on a horse never could. From the air, you could map enemy trench systems, spot hidden artillery batteries, and track troop movements. The first aerial missions were all about being the “eyes of the army.”

When enemy pilots encountered each other in the sky, the interactions were almost comically polite. They would often salute or wave, acknowledging a shared, exclusive brotherhood of the air. This gentlemanly phase didn’t last. Soon, pilots started carrying pistols and rifles, taking potshots at each other in flight—a nearly impossible task. They began throwing things: bricks, heavy wrenches, and even ropes, hoping to snag an enemy’s propeller. The first true aerial weapon was the hand-held grenade, a clumsy and dangerous tool for everyone involved.

Read more

1915: The Propeller Problem and the Fokker Scourge

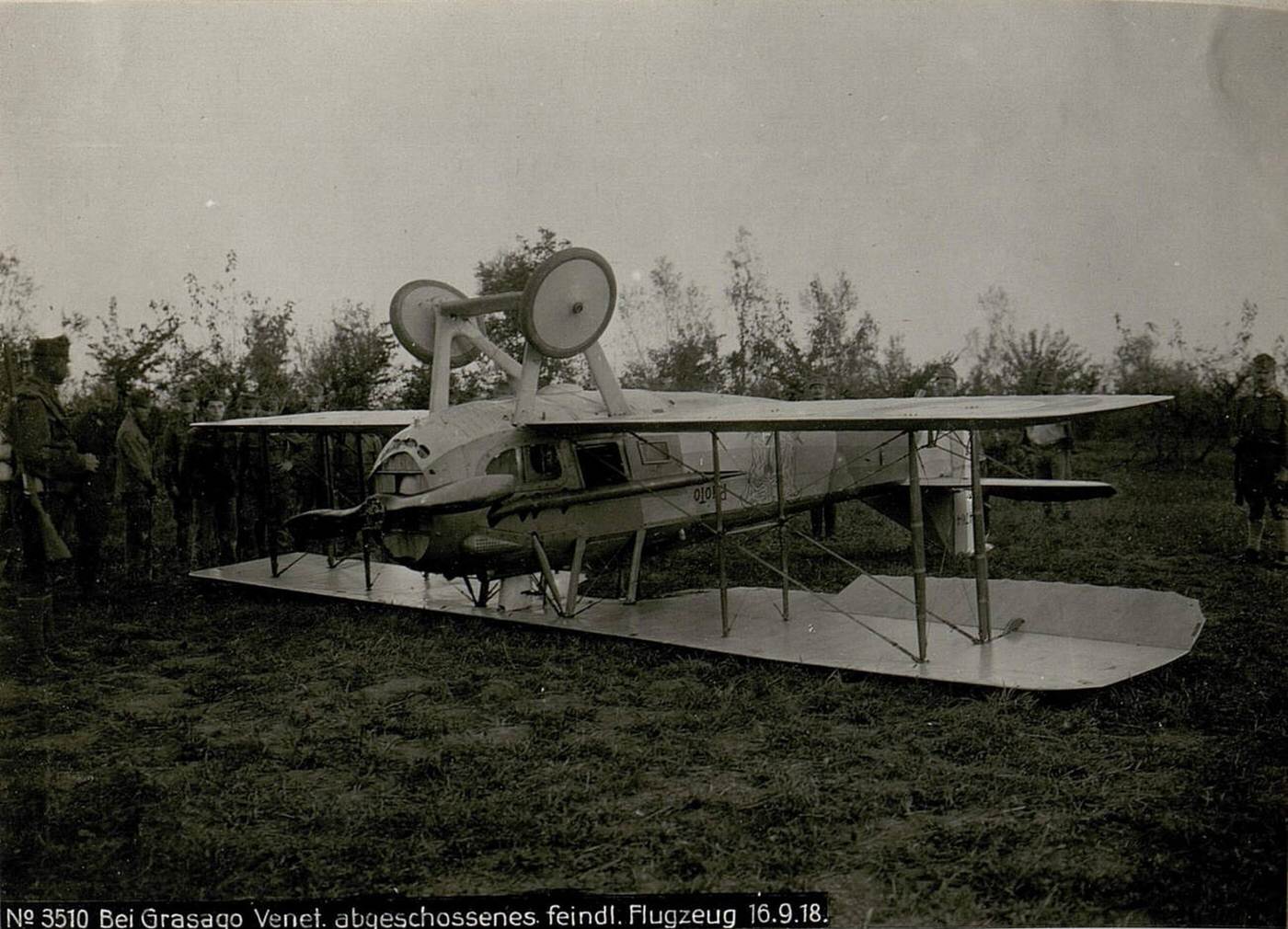

Everyone knew that the key to aerial combat was the machine gun. The problem was figuring out how to use it. If you mounted a gun on the front of the plane, you would shoot your own spinning propeller to pieces. Early solutions were awkward. Some planes, called “pushers,” were designed with the propeller in the back, giving a gunner in the front a clear field of fire. Others had a gunner standing up in a second cockpit, firing a swiveling gun in any direction but forward.

A French pilot named Roland Garros came up with a crude but brilliant solution. He bolted steel plates onto the back of his propeller blades. He could fire straight ahead, and any bullet that happened to hit a blade would hopefully be deflected. It worked, and Garros became the world’s first fighter ace. But his system was incredibly dangerous and put immense stress on the plane’s engine.

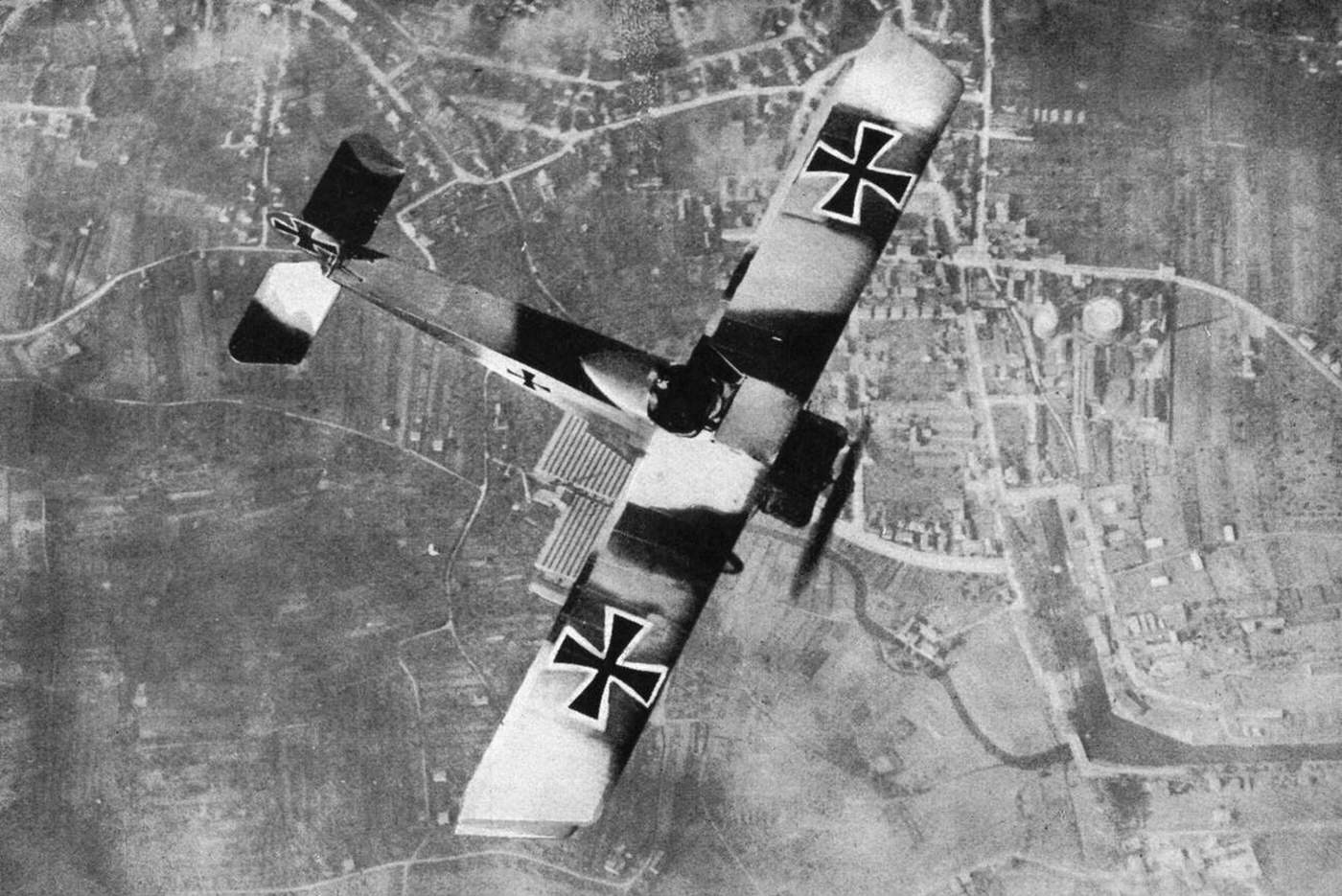

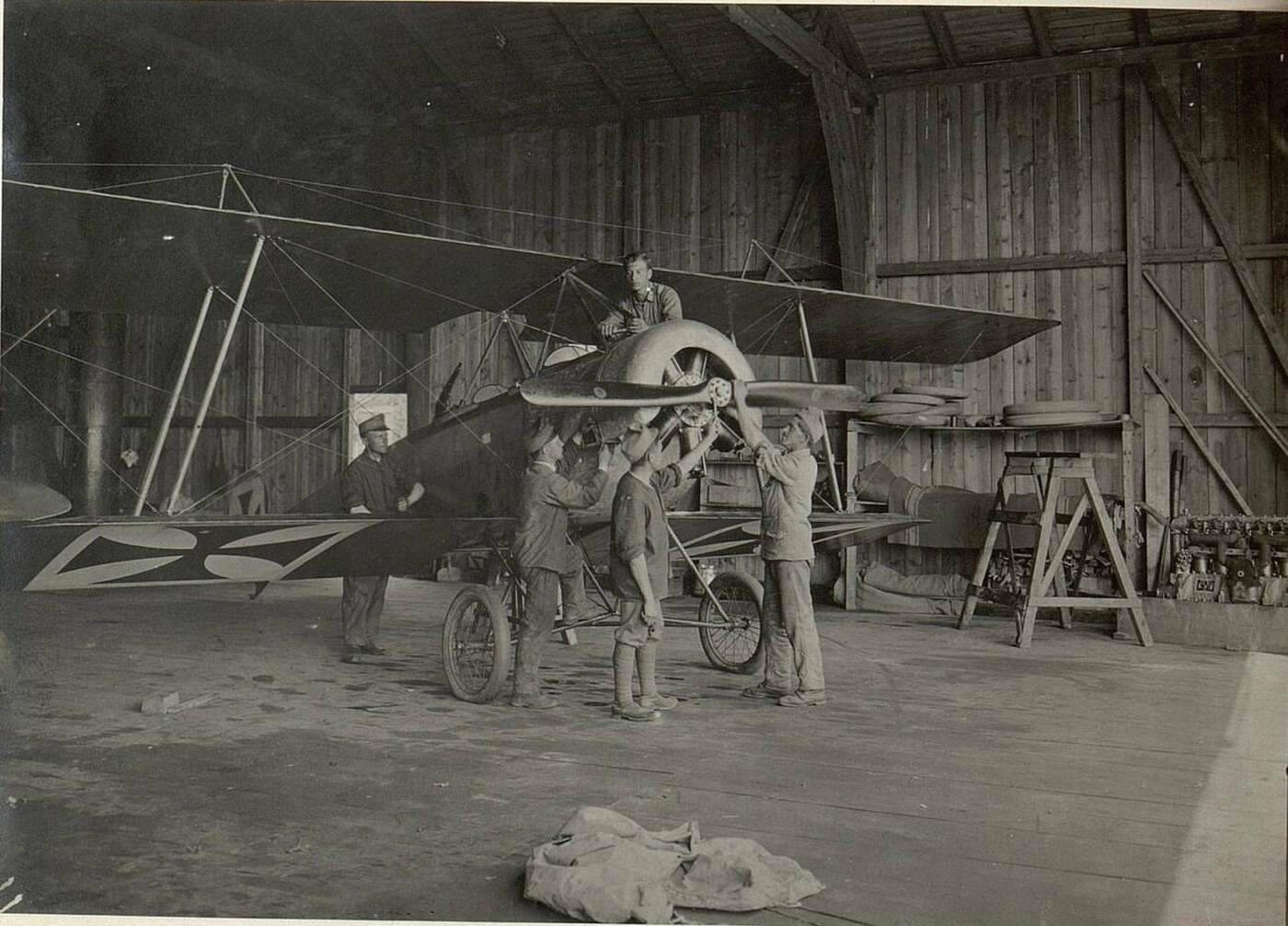

Then came the real game-changer. A Dutch engineer working for the Germans, Anthony Fokker, perfected a device called the synchronization gear. It was a mechanical marvel that linked the machine gun to the plane’s engine. This gear timed the bullets to fire precisely between the spinning blades of the propeller. Now, a pilot could aim his entire aircraft at the enemy and fire a stream of bullets straight ahead.

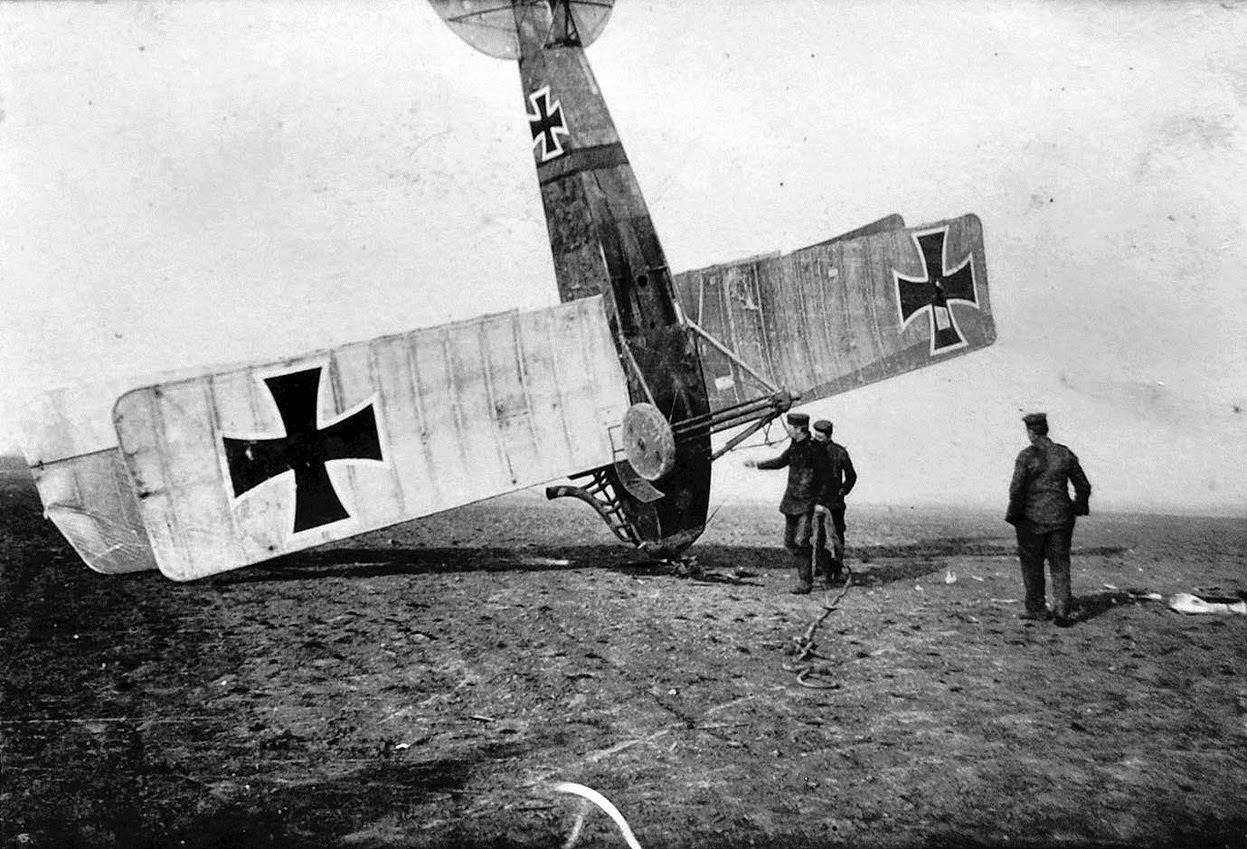

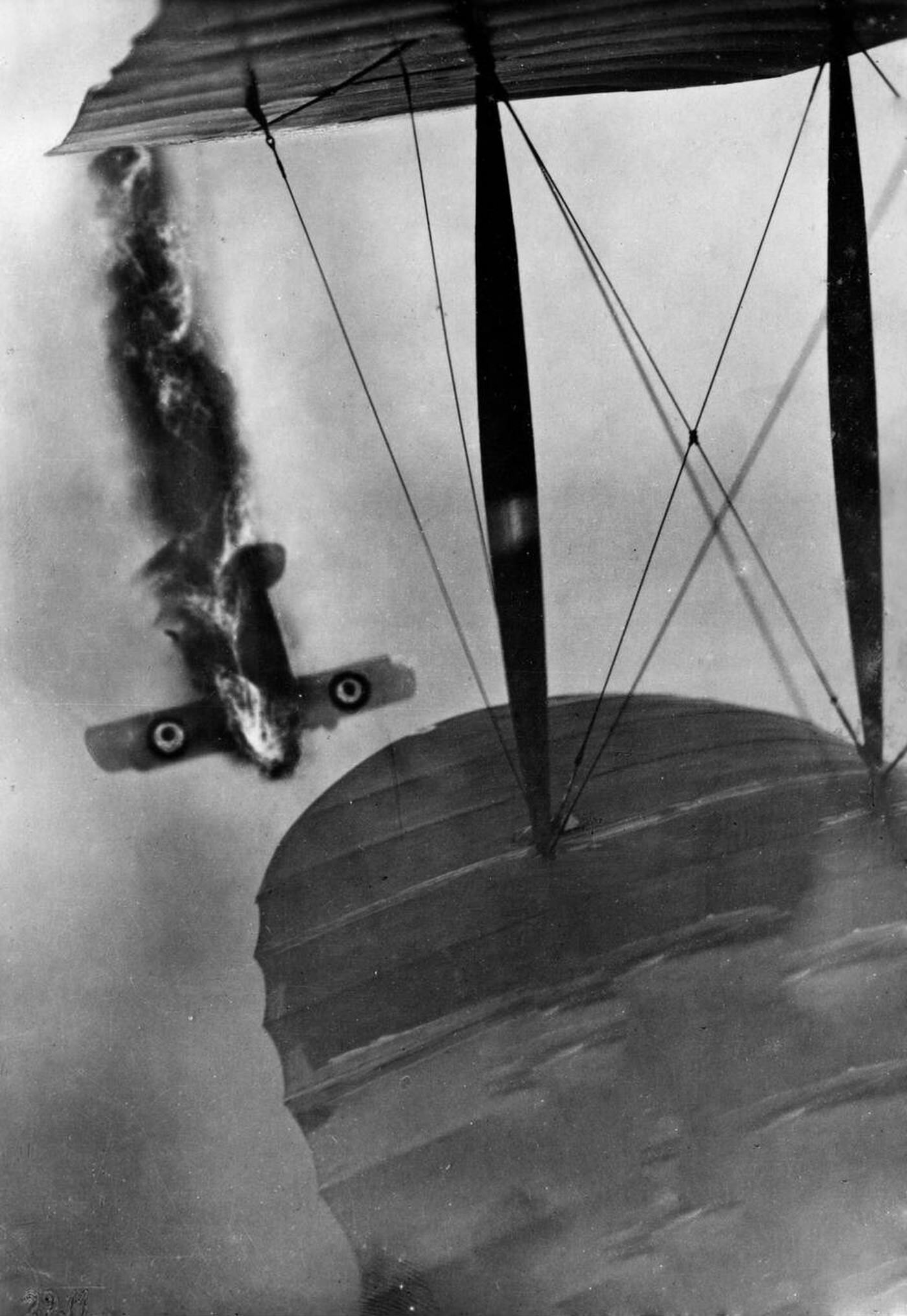

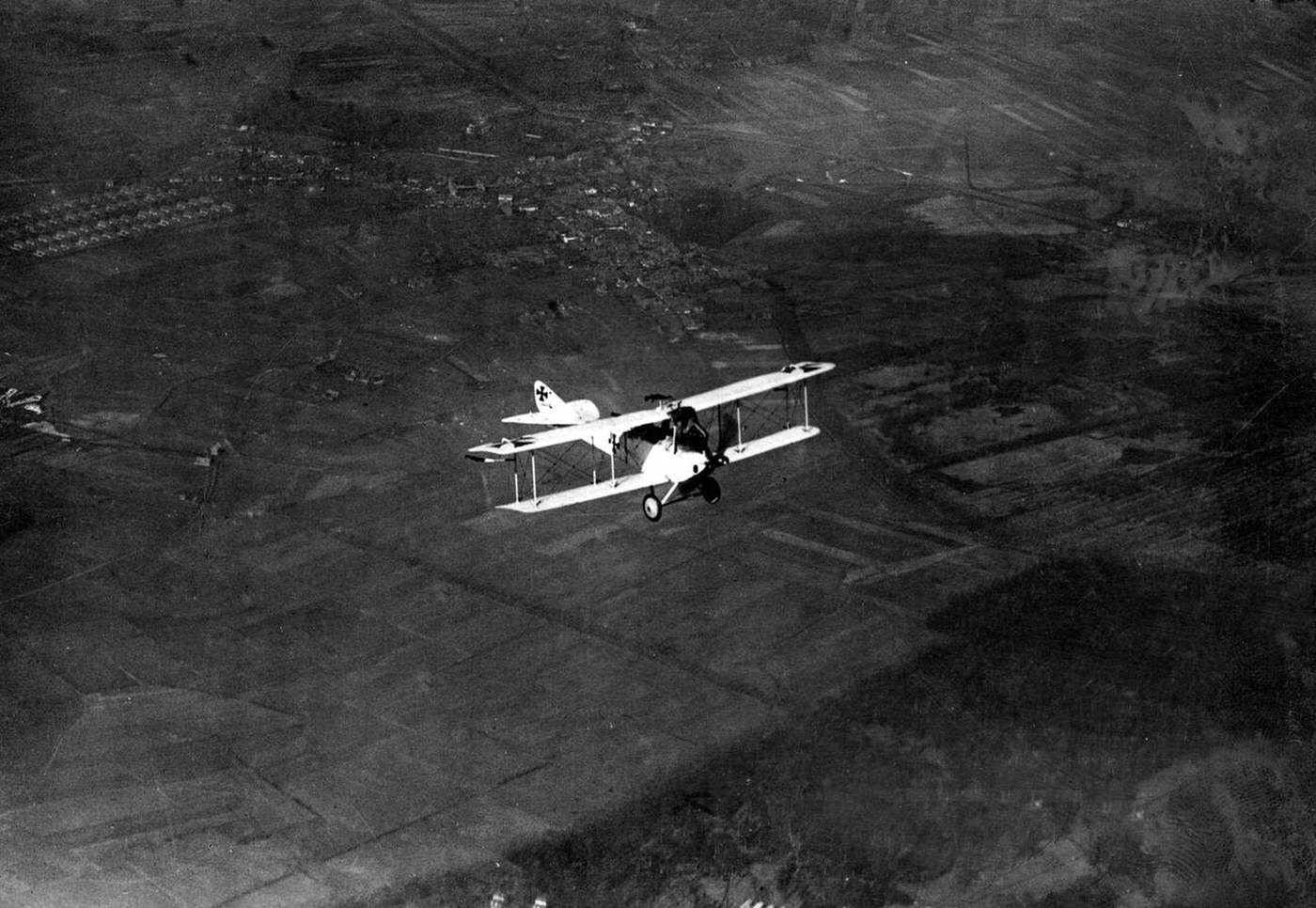

This invention was fitted to the German Fokker Eindecker plane, and it unleashed hell upon the Allies. For months in late 1915, in what became known as the “Fokker Scourge,” German pilots dominated the skies. Allied reconnaissance planes were shot down in horrifying numbers. The age of the friendly wave was over; the age of the dedicated fighter plane, the hunter, had begun.

1916-1917: The Dogfight and the Birth of the Ace

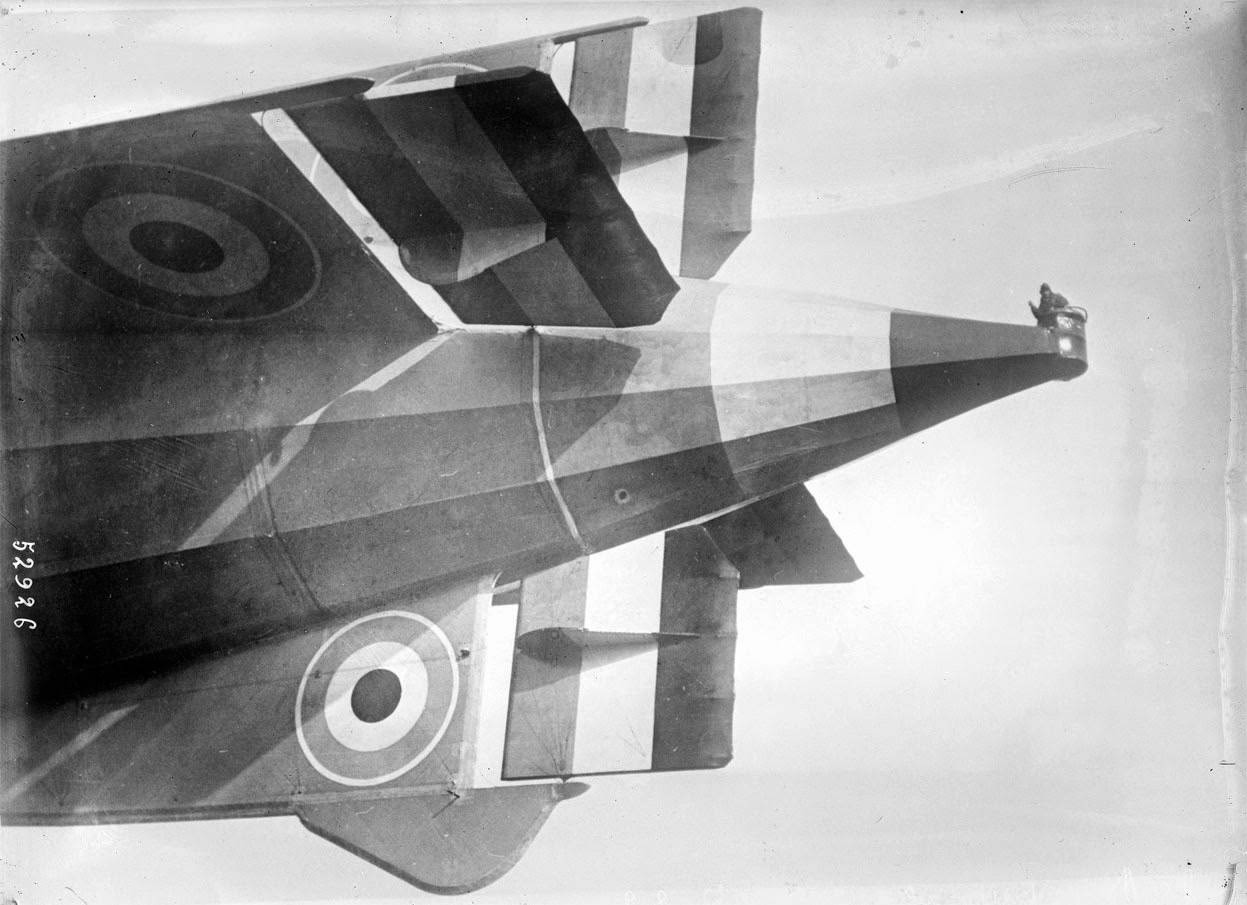

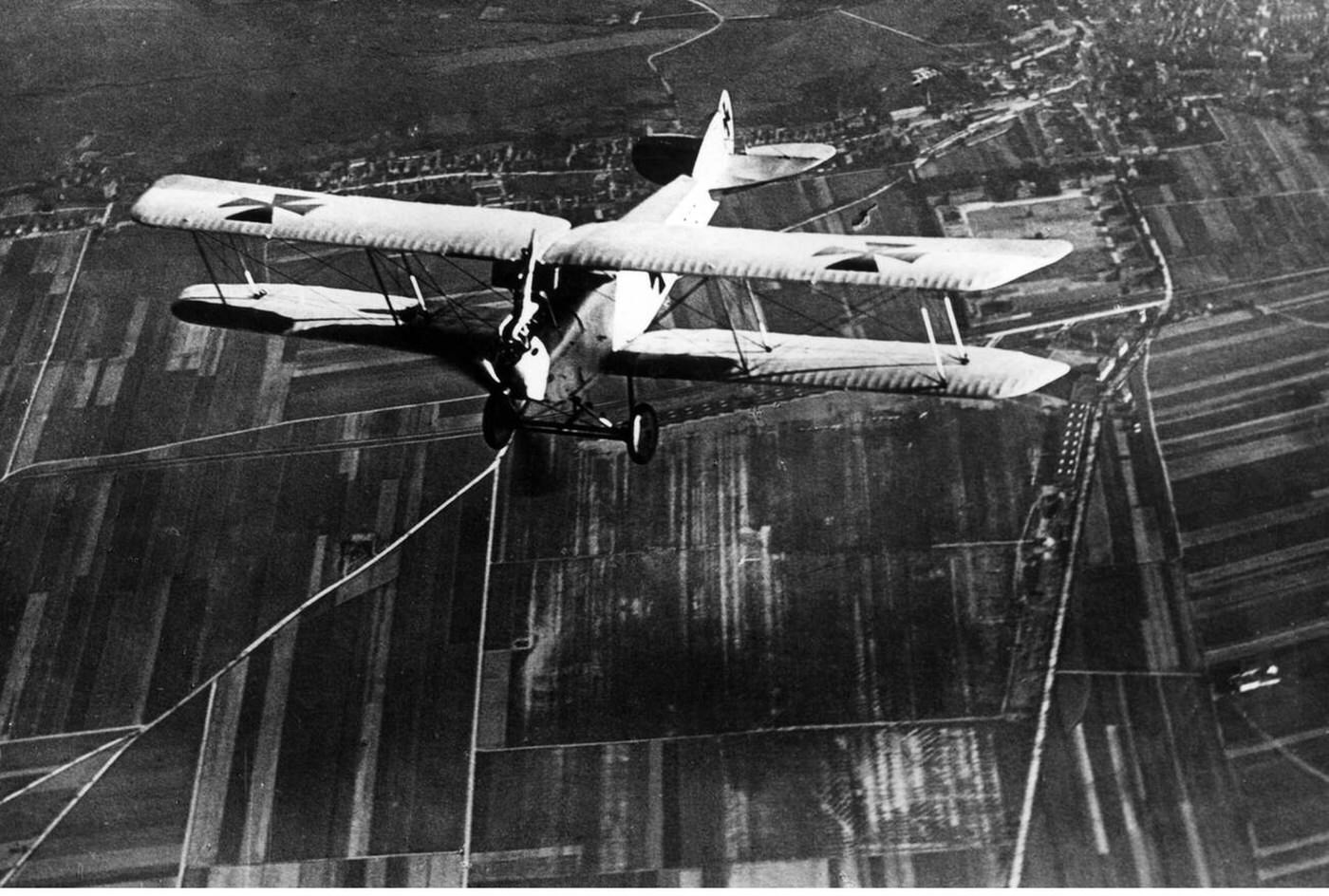

The Allies were desperate. Eventually, they managed to capture a crashed Fokker, reverse-engineer the synchronization gear, and develop their own versions. By 1916, both sides had effective fighter planes like the British Sopwith Pup and the French Nieuport 17. The sky became a dueling ground for these new aerial knights.

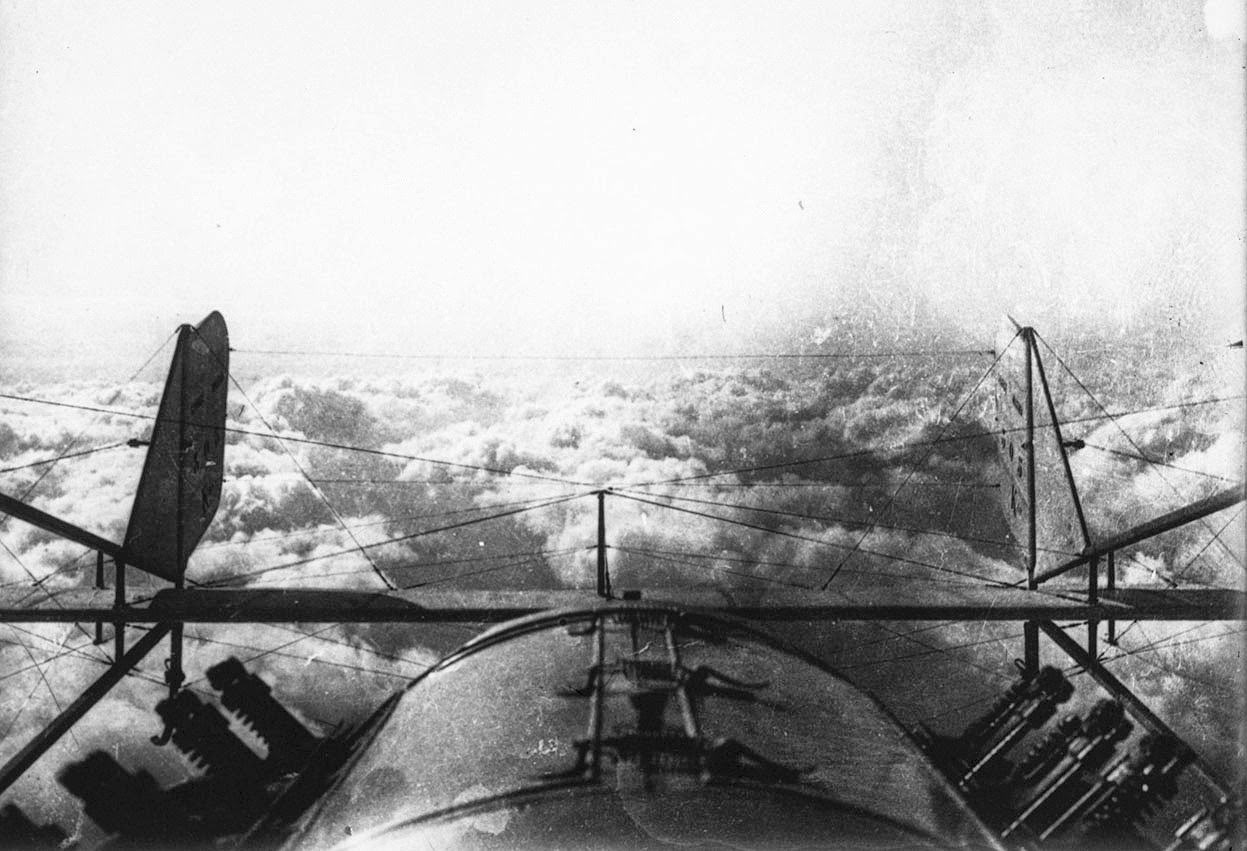

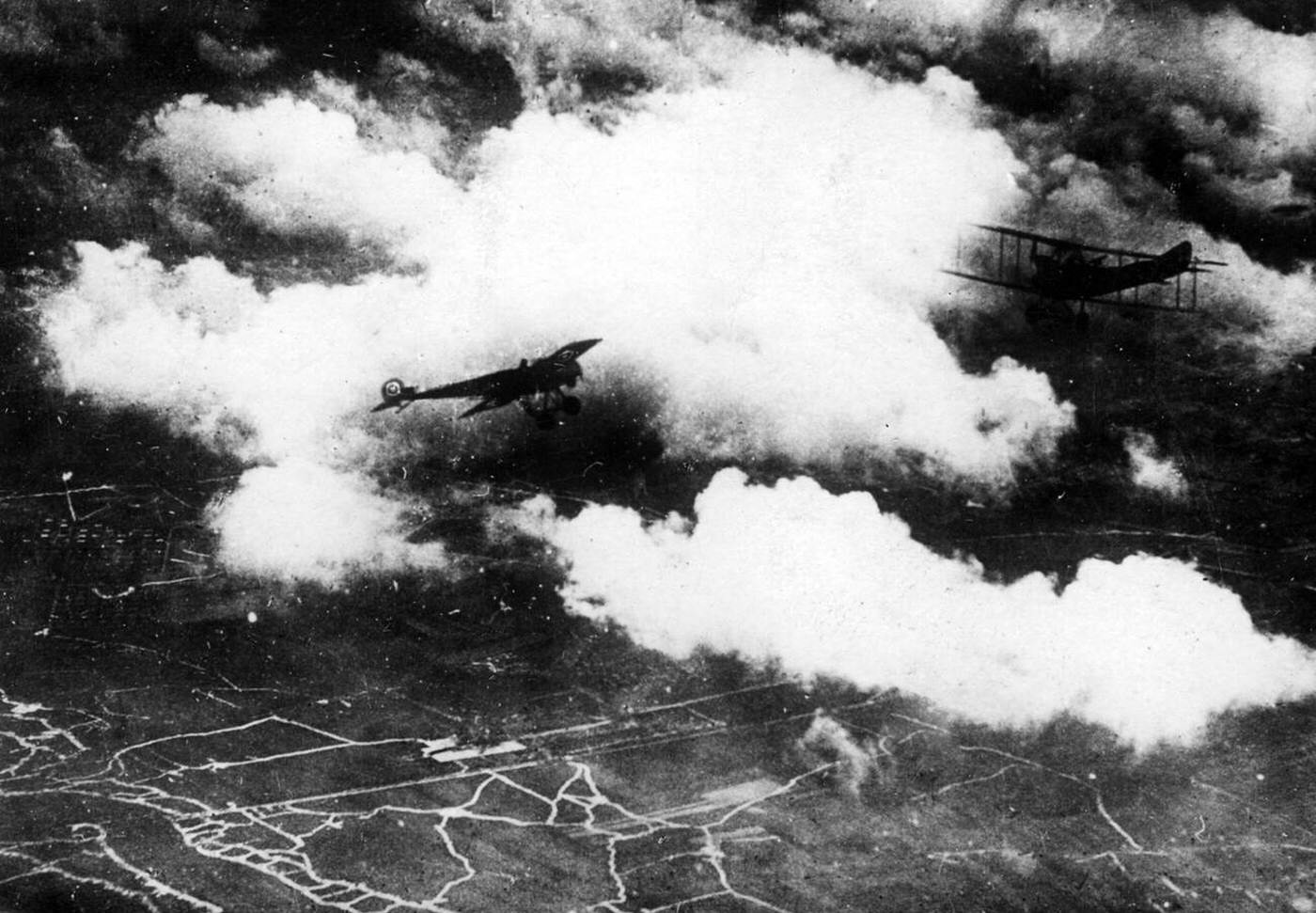

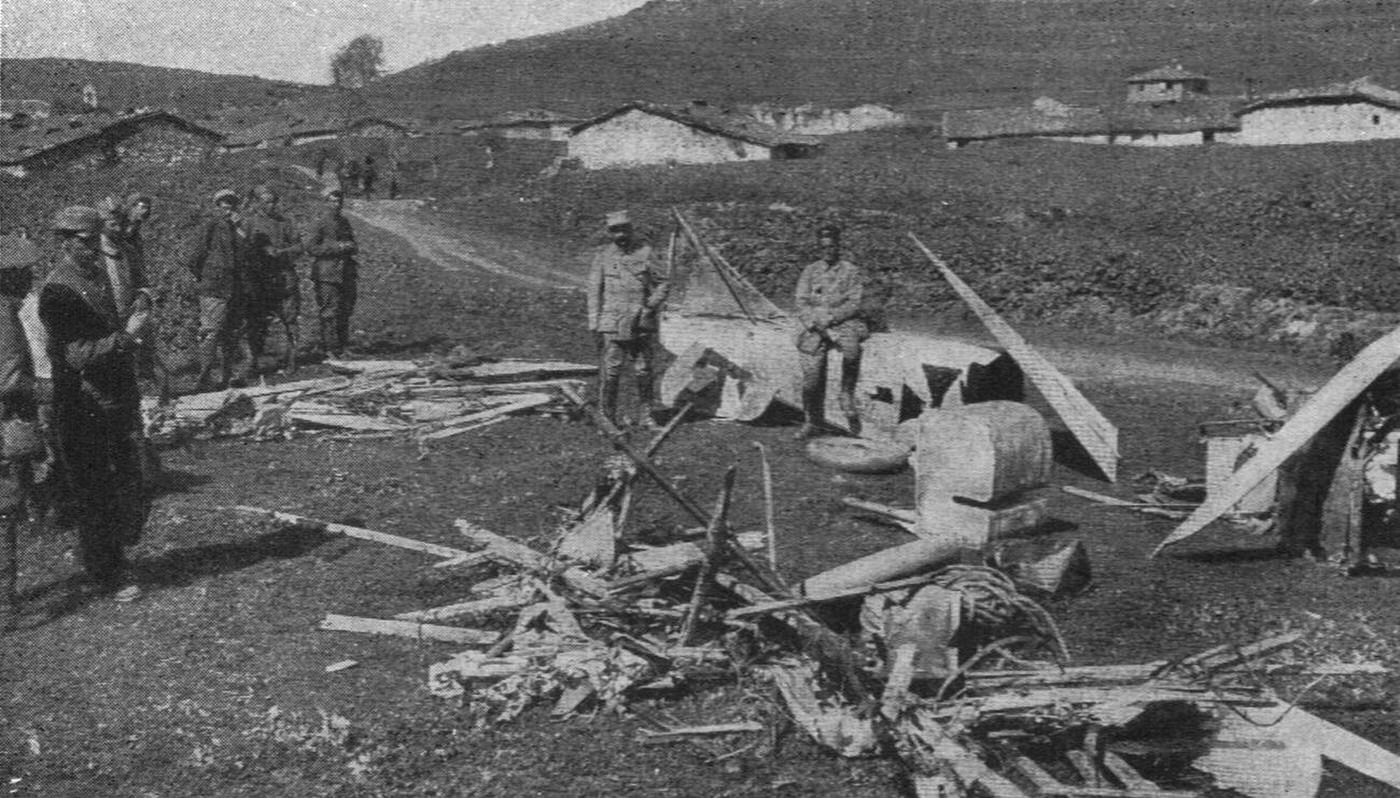

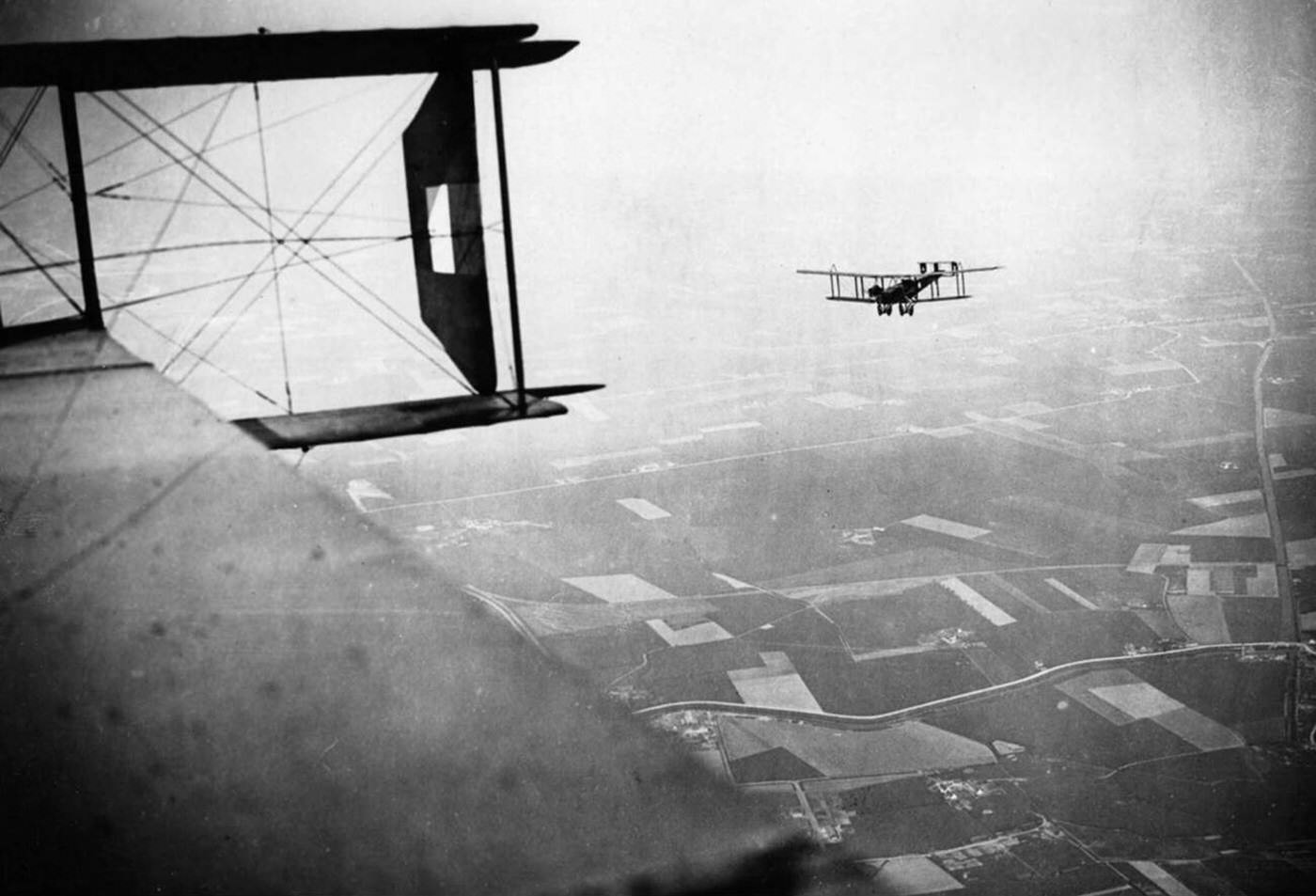

The dogfight was a chaotic, three-dimensional battle of nerve and skill. Pilots flew in tight, swirling formations, trying to get on an enemy’s tail to line up a shot. The planes were still incredibly fragile. A steep dive could rip the fabric from the wings. Engines could stall without warning. A pilot’s machine guns could jam right at the critical moment, leaving him helpless.

A grim reality of this new combat was the absence of parachutes. High command on both sides resisted issuing them to fighter pilots, fearing it would encourage them to abandon their expensive aircraft. If your plane was shot to pieces or caught fire, your choices were to burn to death or jump.

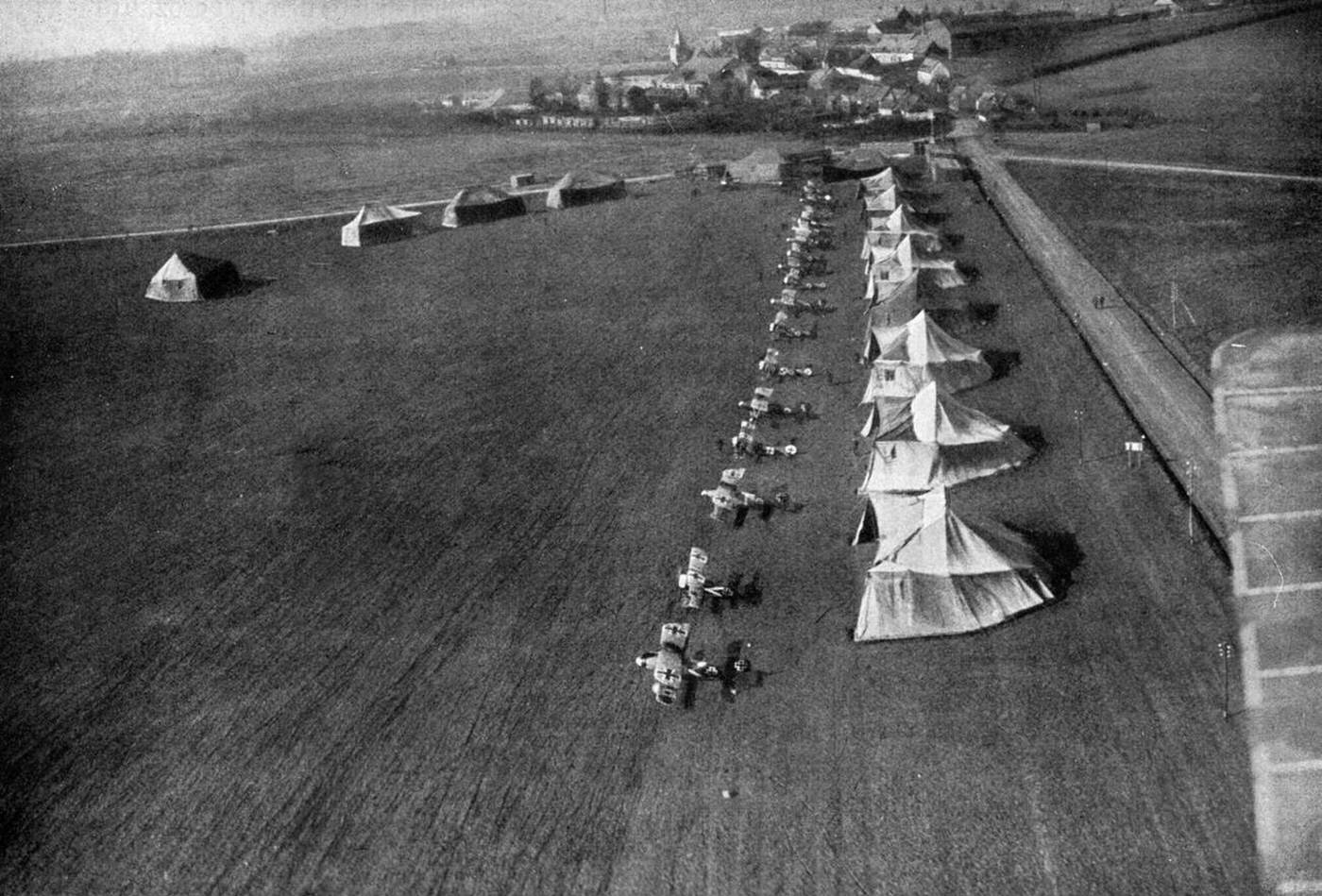

Out of this brutal arena, heroes were born. A pilot who shot down five or more enemy planes was crowned an “ace.” These men became national celebrities, their faces printed on postcards and their victories celebrated in newspapers. The most famous was Germany’s Manfred von Richthofen, the “Red Baron,” who painted his Fokker triplane a blood-red color and amassed 80 confirmed kills. Other legendary aces included France’s René Fonck and America’s Eddie Rickenbacker. But for every celebrated ace, thousands of pilots perished in flames. For a new pilot arriving at the front in 1917, the average life expectancy could be as short as three weeks.

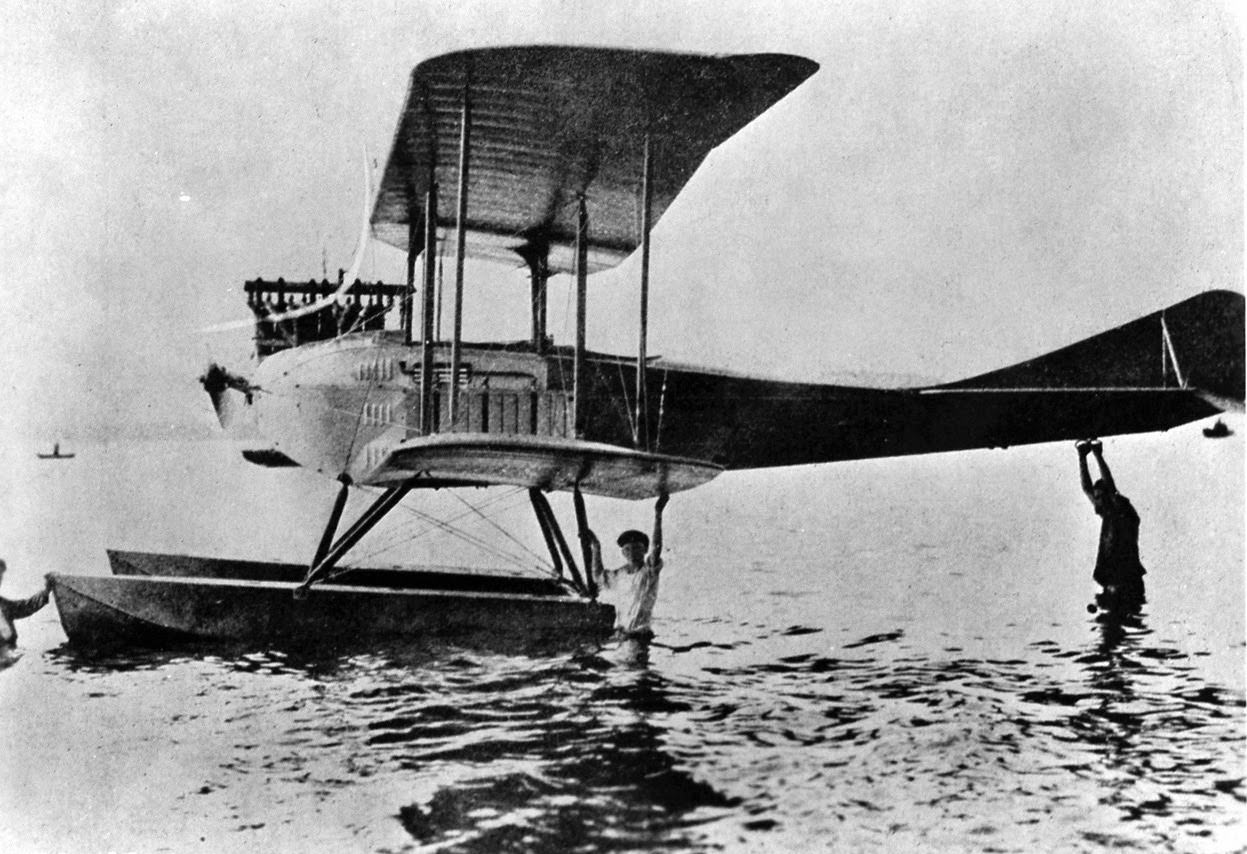

1918: New Terrors from Above

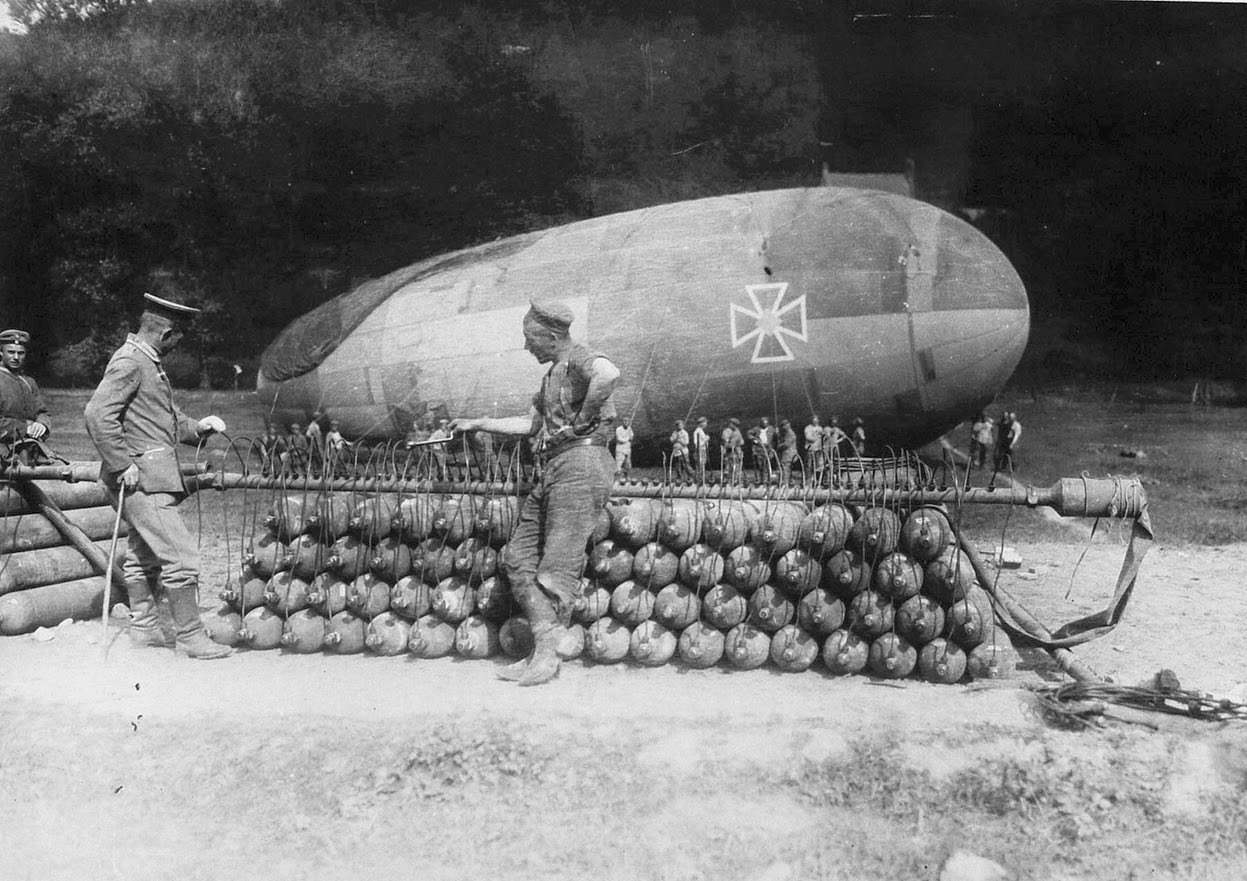

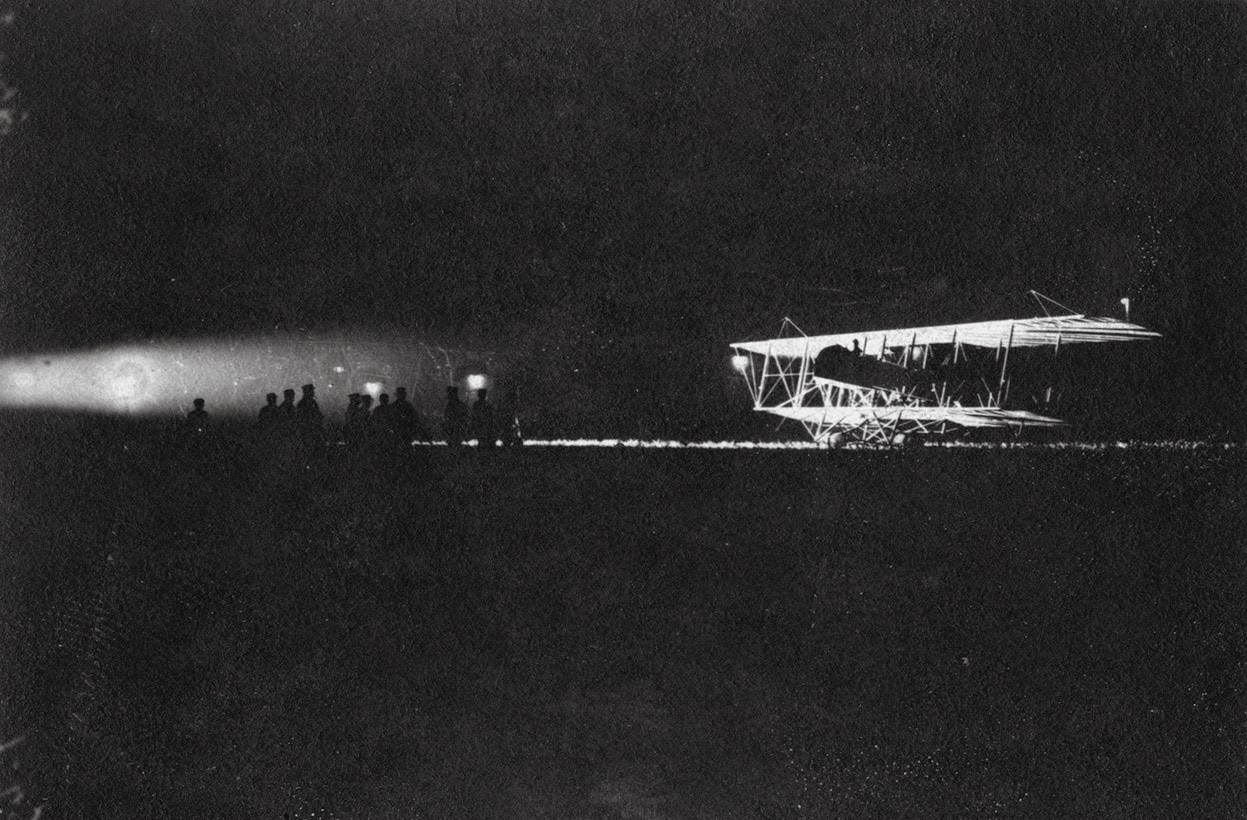

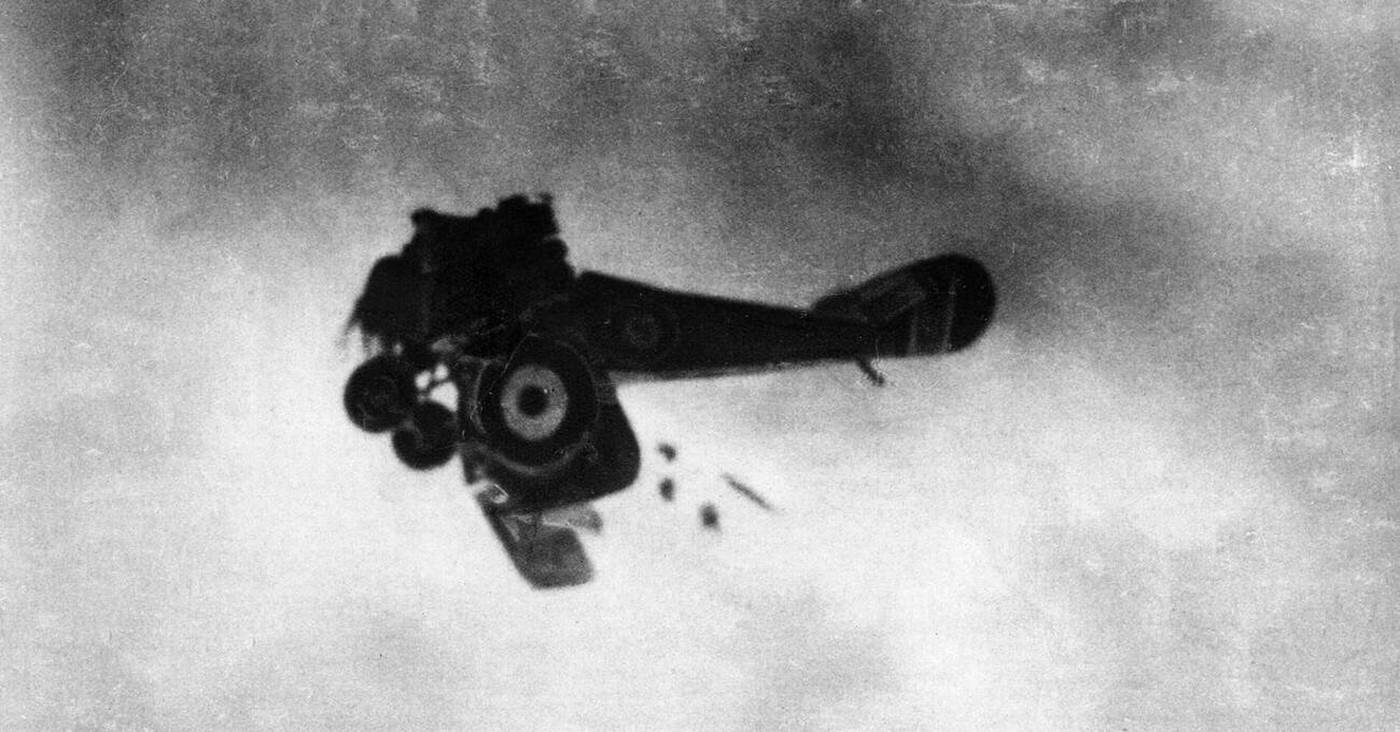

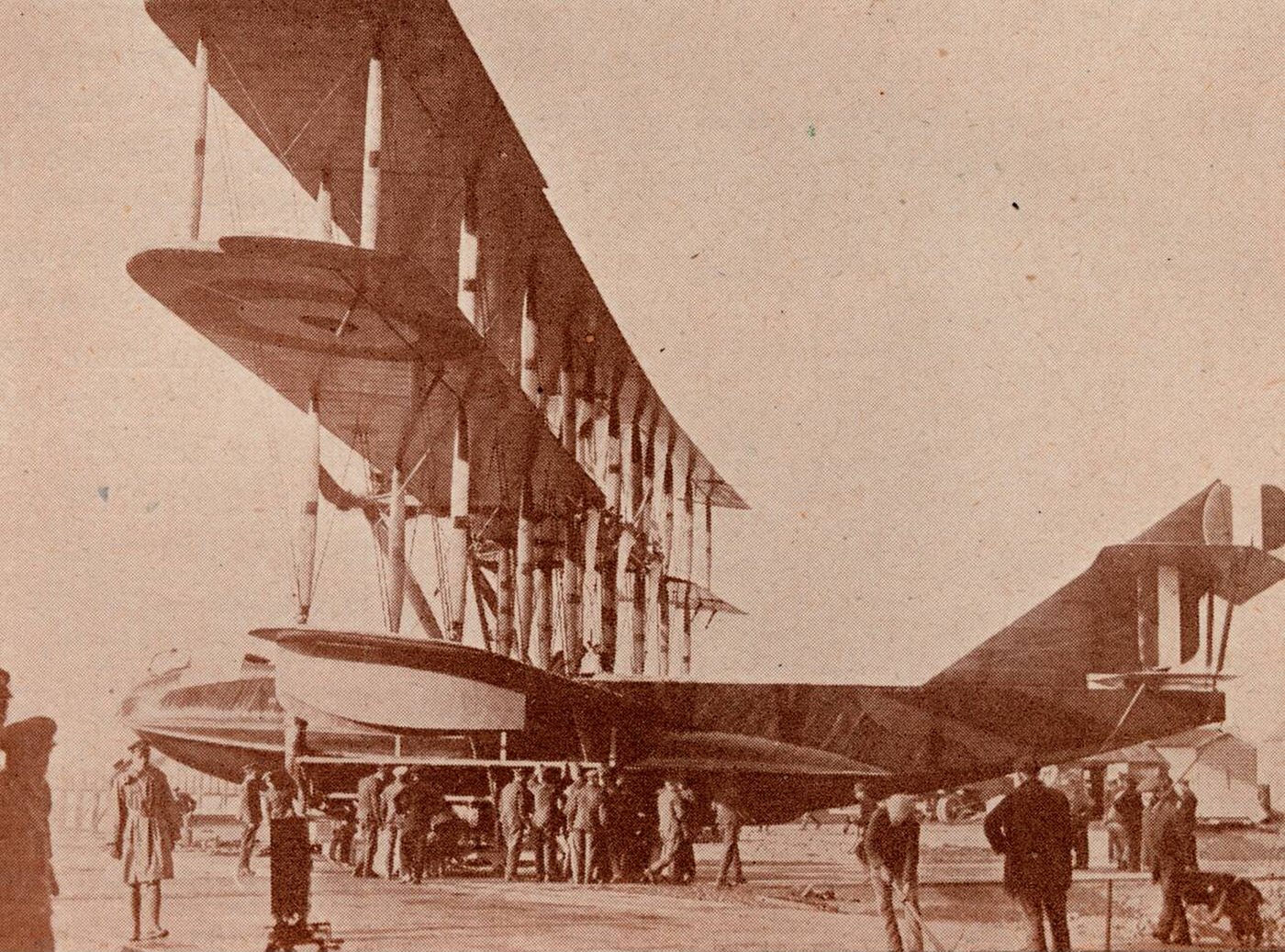

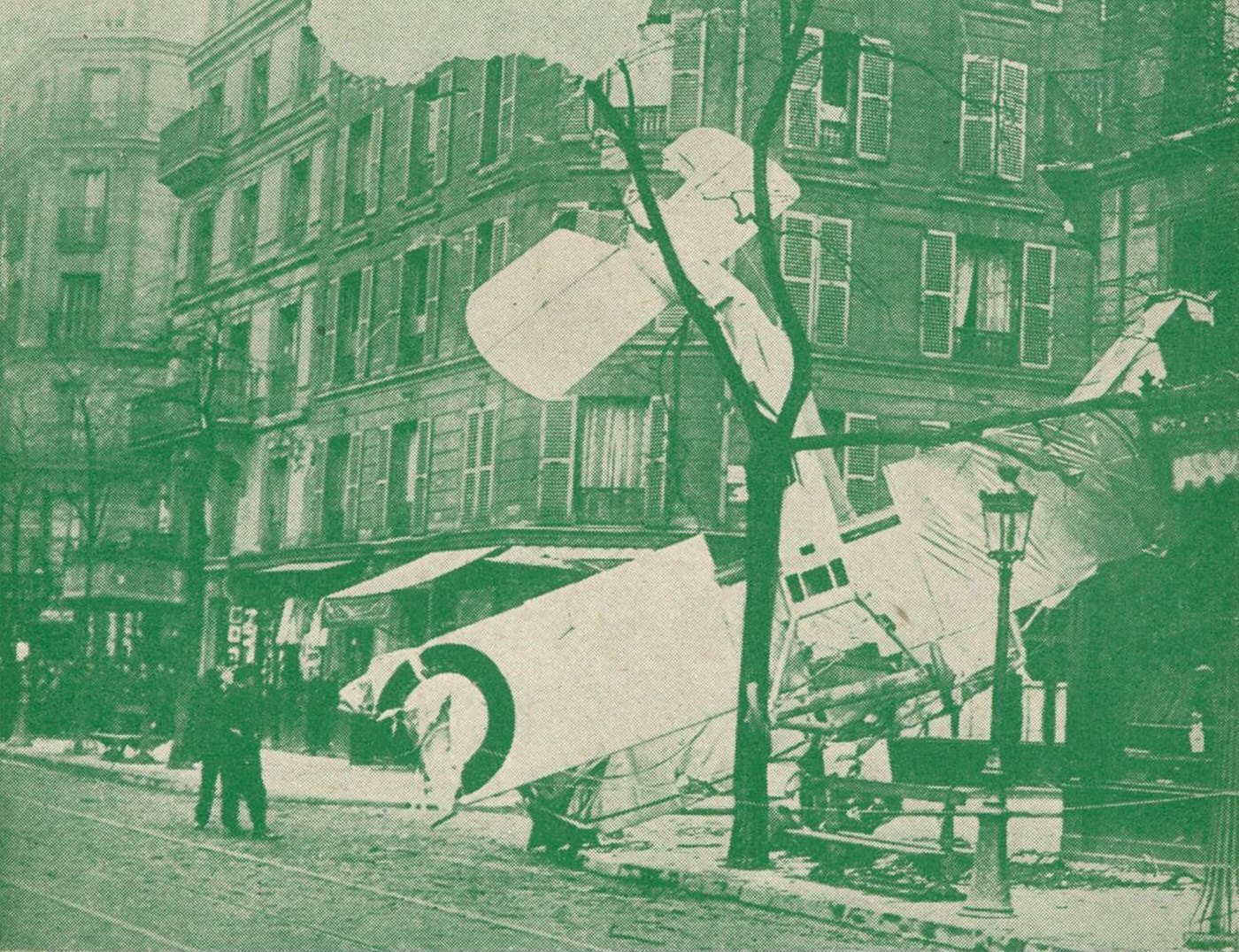

As the war dragged on, the roles of aircraft expanded beyond just reconnaissance and dogfighting. Both sides began to develop large, multi-engine bombers. Early bombing missions involved the co-pilot simply leaning out of the cockpit and dropping bombs by hand. By the end of the war, massive planes like the German Gotha G.V. and the British Handley Page Type O were flying deep into enemy territory to bomb factories, railways, and cities.

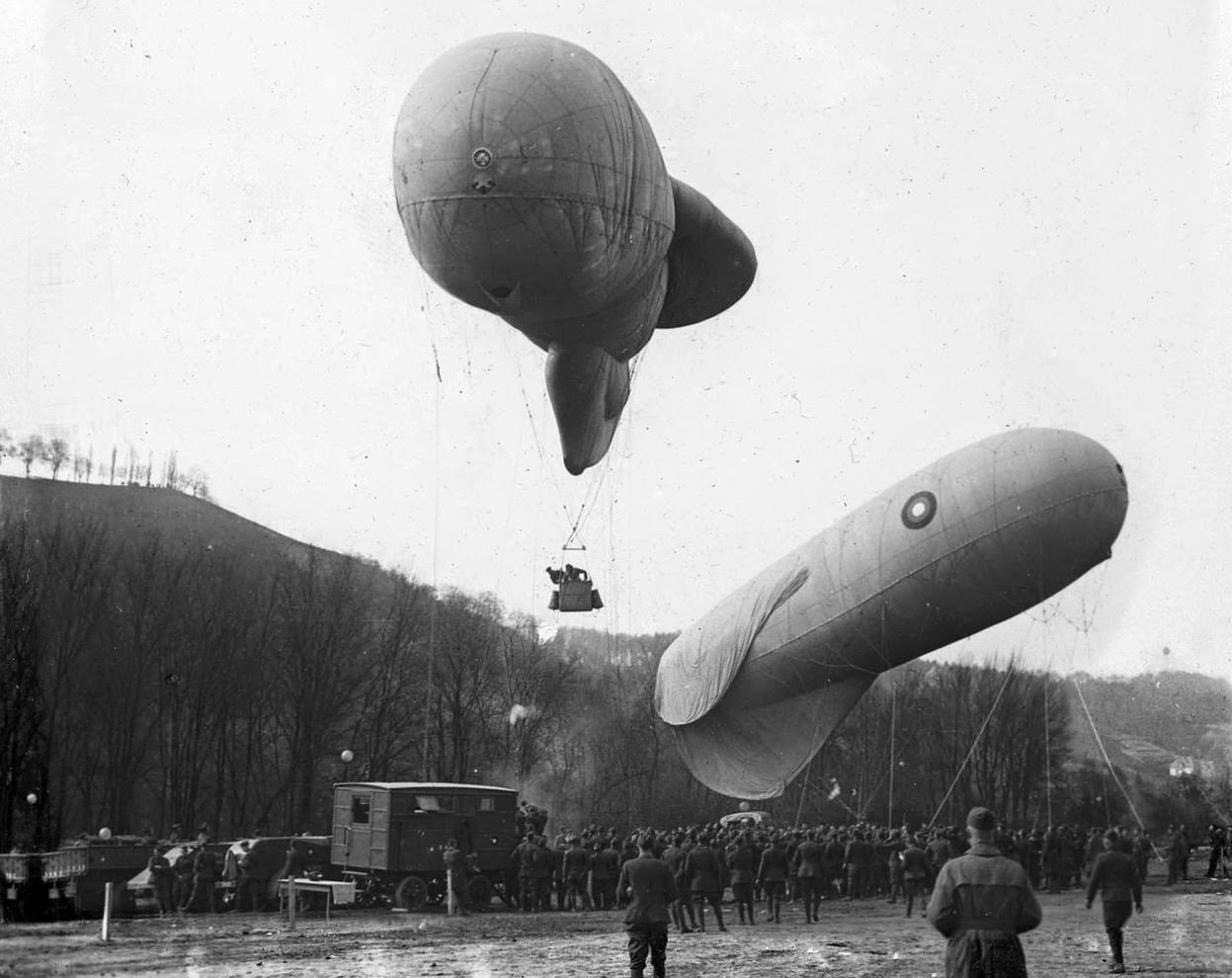

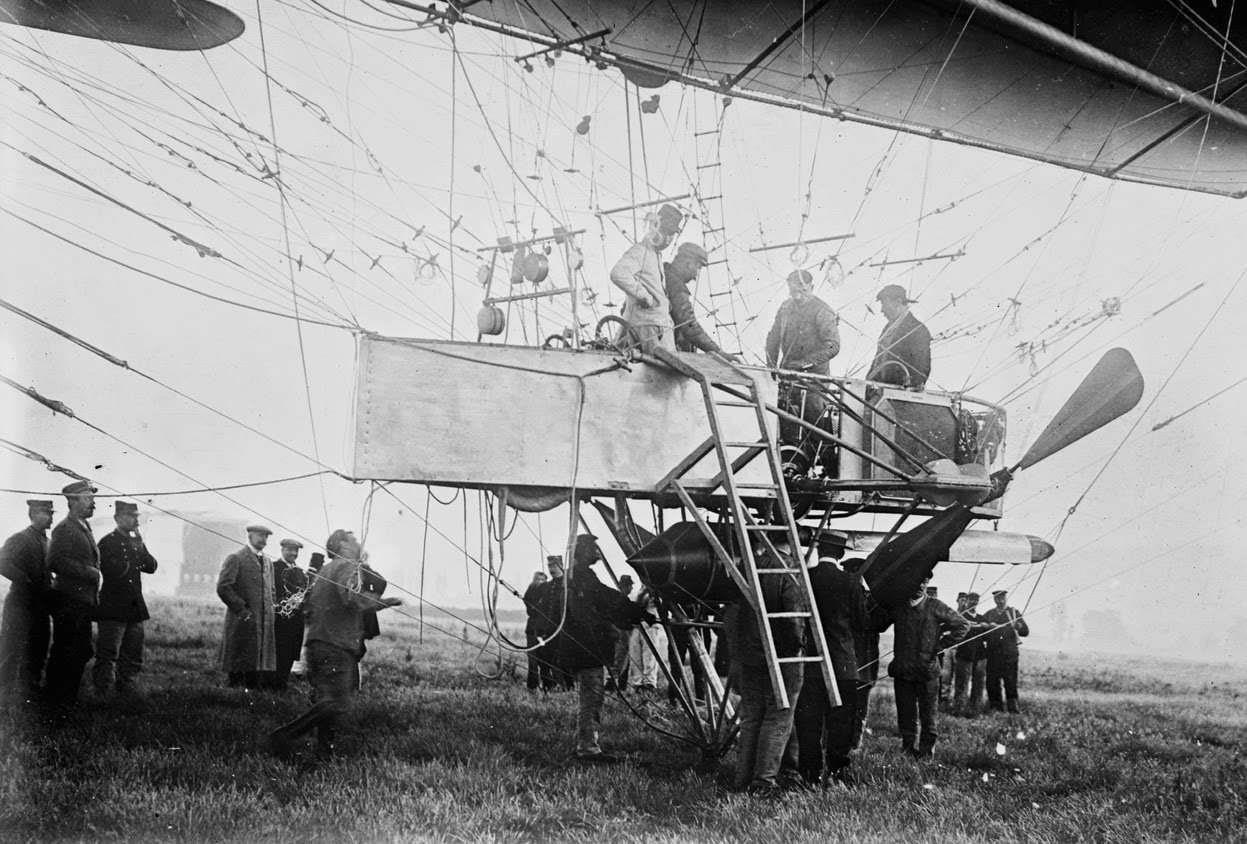

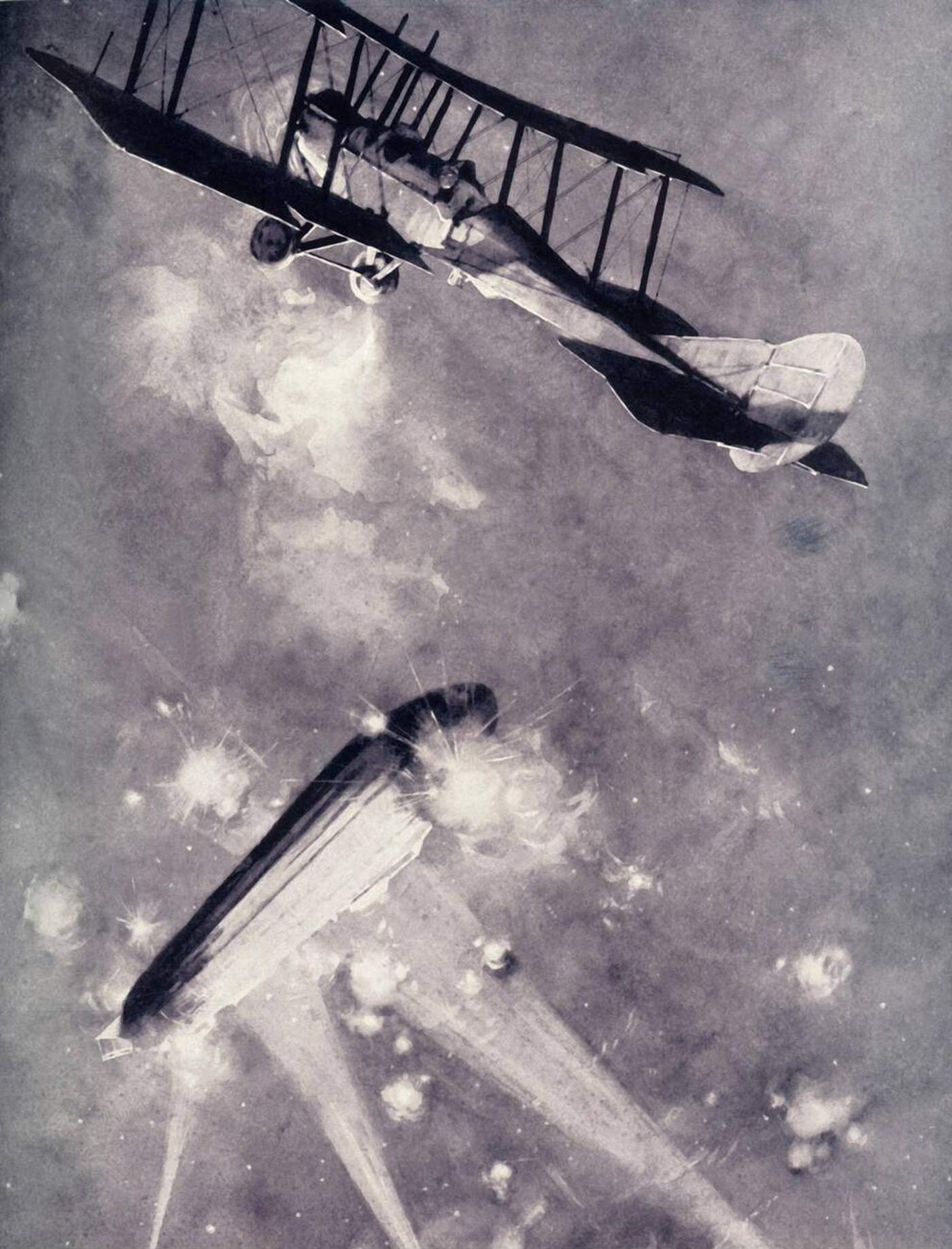

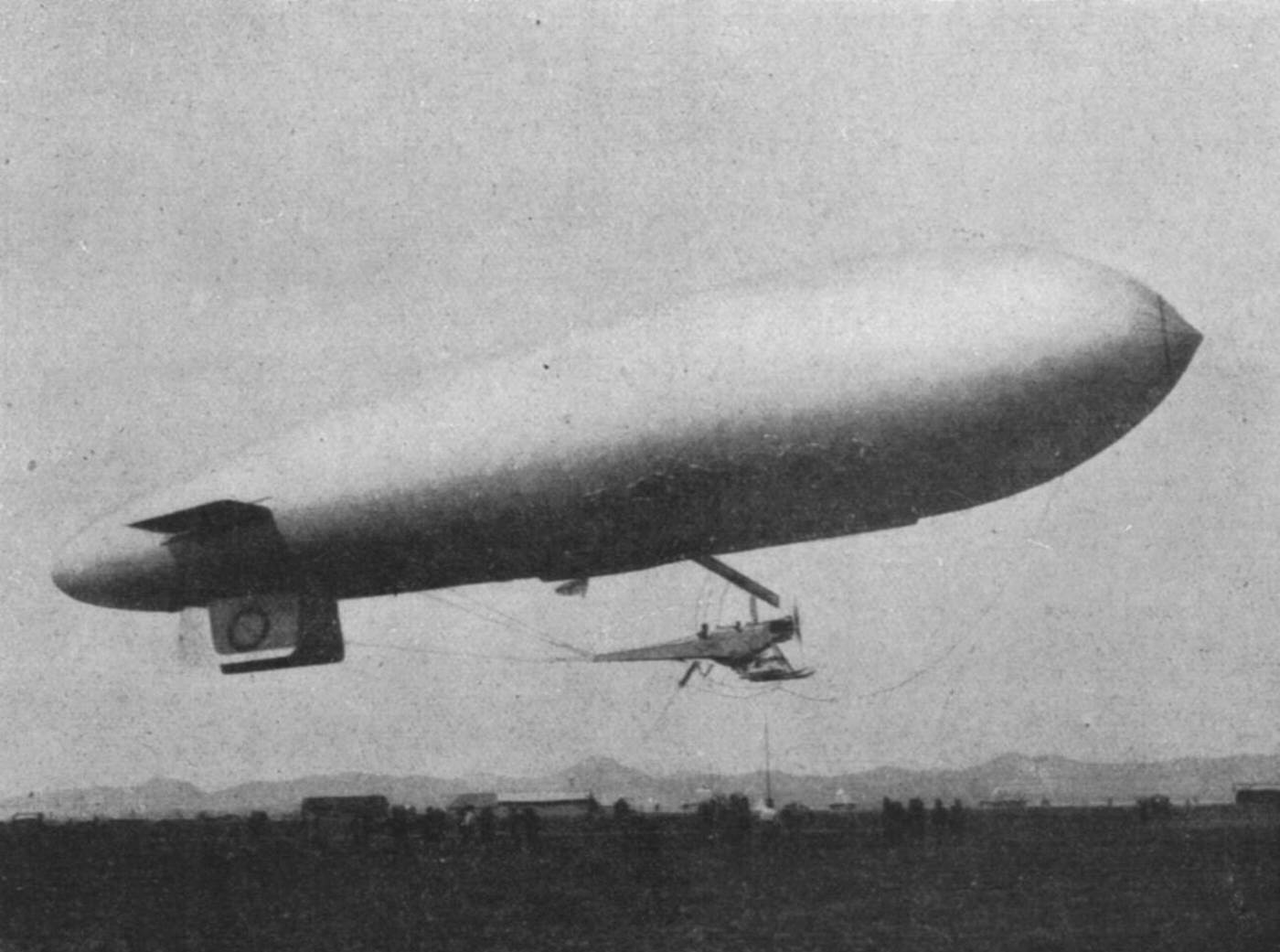

The Germans also unleashed a new weapon of psychological terror: the Zeppelin. These enormous, silent airships flew high over the English Channel at night to drop bombs on London. The raids caused widespread panic, but the Zeppelins themselves were incredibly vulnerable. They were filled with highly flammable hydrogen gas, and a single incendiary bullet from a fighter plane could turn one into a blazing inferno.

In the final year of the war, a new type of plane emerged: the ground-attack aircraft. These were heavily armored planes, like the German Junkers J.I, designed to fly low over the trenches and directly support the infantry. They would strafe enemy positions with machine-gun fire and drop small bombs, bringing the terror of the skies down to the mud of the battlefield. The war that began with pilots waving at each other had evolved into a complex, mechanized, and deadly form of industrial warfare, with huge aerial armadas clashing in the skies and armored beasts attacking the trenches below.