In the early 1970s, the Ohio River was a paradox. It was the muscular, steel artery of America’s heartland, a hardworking highway pushing barges loaded with coal and chemicals, feeding the insatiable hunger of the factories that lined its banks. But it was also a sewer. For decades, the cities and industries along its 981-mile journey had treated it as a convenient, bottomless trash can. This was a river of two faces: one of immense power and prosperity, the other of foul, chemical-laced sickness.

Capturing this complicated truth was the job of a photographer named William Strode III. Working for a brand-new government agency called the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Strode was part of a groundbreaking project called Documerica. The mission was to create a photographic record of the state of the environment across the nation. In the Ohio Valley, Strode pointed his camera not just at the pollution, but at the people living in its shadow, creating a stunning, colorful, and often shocking portrait of life on a river at a crossroads.

The Industrial Lifeline

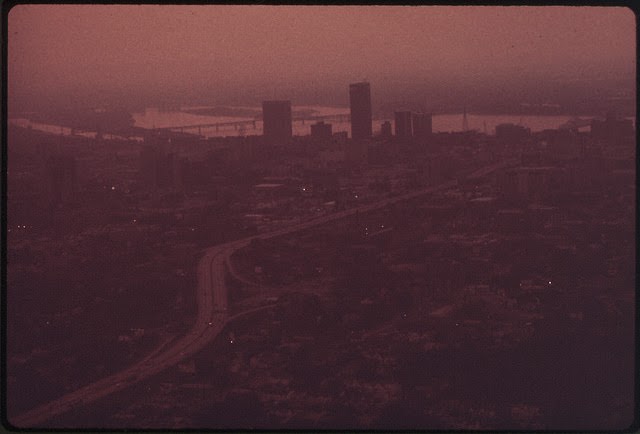

From Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, down to Cairo, Illinois, the banks of the Ohio were a fortress of American industry. Towering steel mills in towns like Steubenville and Weirton belched thick, colored smoke into the sky, a constant sign of production. Chemical plants, vast and sprawling, hummed day and night, their pipes extending like tentacles towards the river’s edge. This industrial might was the engine of the region’s economy. It put food on the table for hundreds of thousands of families.

Read more

Life was tied to the rhythm of the river and the factory whistle. Men worked grueling shifts in the intense heat of the mills, their bodies stained with grease and grime. The river itself was a constant hive of activity. Powerful towboats pushed massive barges, some stretching longer than three football fields, laden with coal to power the nation or chemicals destined for factories downstream. The river was a workplace, a source of pride and identity. To the people who lived there, the smoke in the sky and the traffic on the water were the sights and sounds of prosperity.

A Poisoned Playground

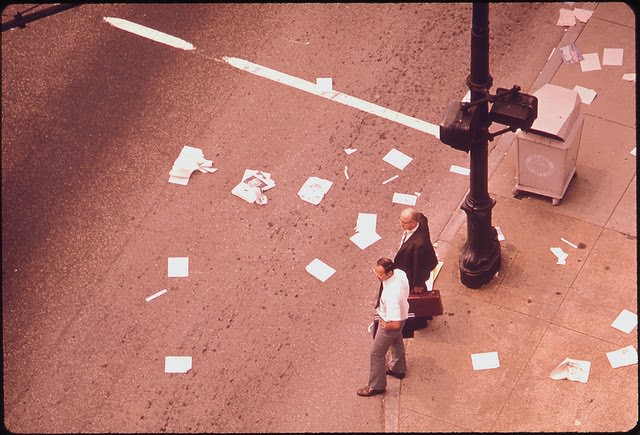

The prosperity, however, came at a staggering environmental cost. The Ohio River had become one of the most polluted waterways in the country. Industries used the water for cooling and processing, and then dumped it right back in, laced with a toxic cocktail of chemicals, heavy metals, and oil. Cities and towns, many lacking modern sewage treatment facilities, discharged raw or poorly treated human waste directly into the current.

The pollution was something you could see and smell. In some stretches, the water flowed with a sickly, rust-orange tint from acid mine drainage. Oily sheens shimmered on the surface, creating rainbow patterns on top of the brown water. Foul odors would hang in the air, a constant reminder of the river’s sickness.

Biologists at the time described sections of the river as “biologically dead.” This meant the water was so starved of oxygen and so full of poison that almost nothing—no fish, no insects, no plants—could survive. It was a sterile, moving wasteland. And yet, people still lived alongside it. William Strode’s photographs captured this jarring reality. He photographed children playing on riverbanks just yards away from pipes spewing discolored effluent. He photographed fishermen casting their lines into the murky water, hoping to catch something edible, but often pulling out fish with strange tumors or a chemical taste.

Life Goes On in the Shadow of the Smokestacks

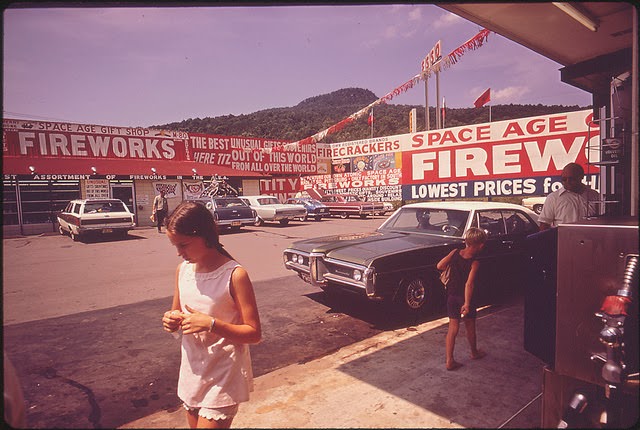

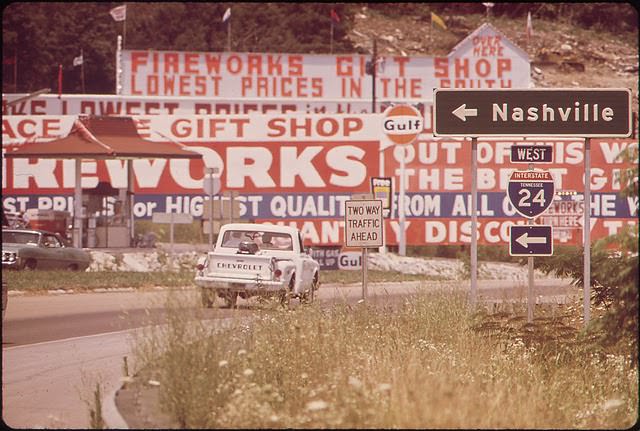

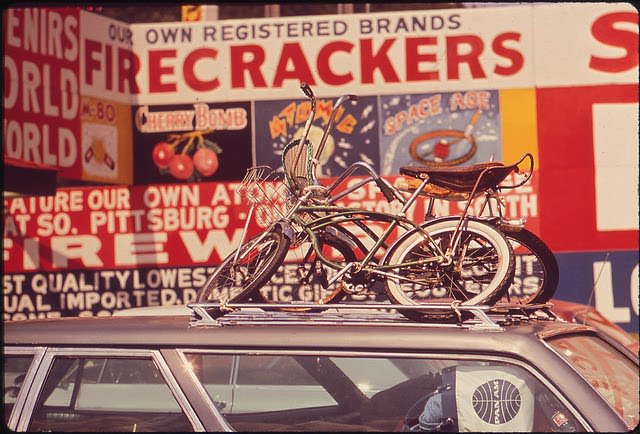

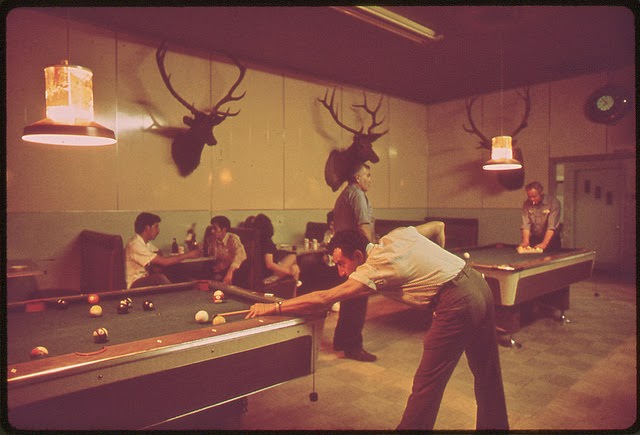

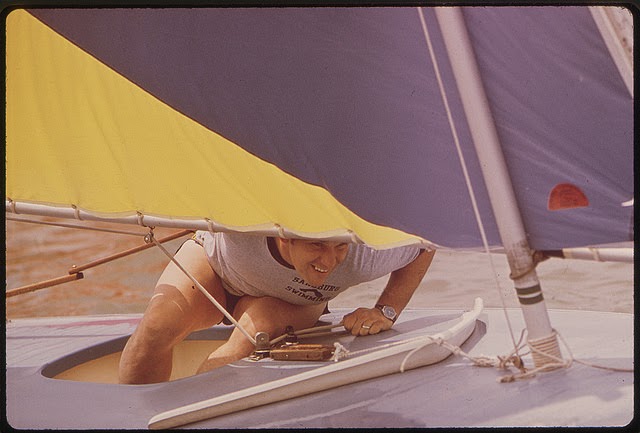

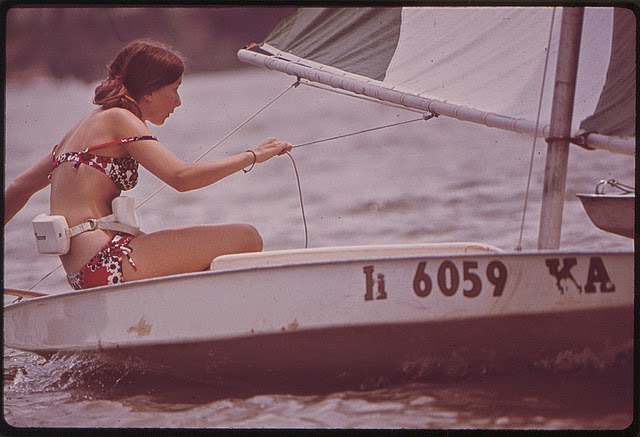

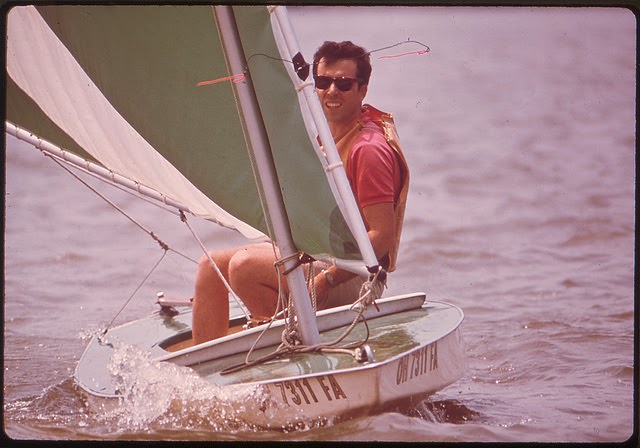

Strode’s work for Documerica was brilliant because it didn’t just show the filth; it showed the resilience of the human spirit amidst the decay. His lens captured the everyday life that persisted. He photographed families enjoying a Sunday picnic in a riverside park, with the smokestacks of a power plant dominating the background. He photographed teenagers waterskiing, their youthful energy a stark contrast to the contaminated water spraying around them.

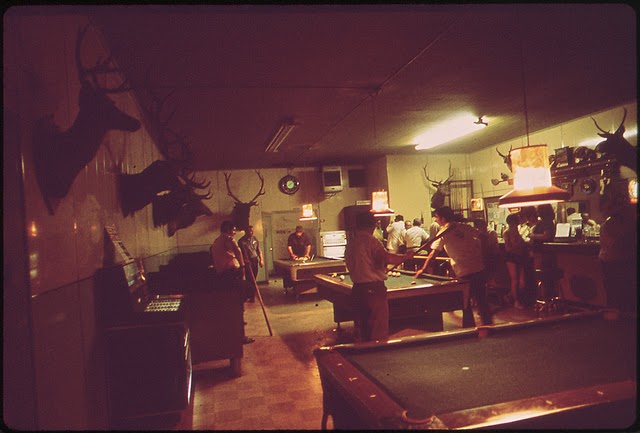

In the small river towns, life had a unique character. People knew their neighbors. There were church socials, high school football games, and a deep sense of community forged by a shared reliance on the river and the industries it served. They were proud of their work and their towns. The pollution was often seen as an unavoidable, if unpleasant, part of the deal. It was the price of a steady paycheck. Many had a fatalistic acceptance of the situation; it was just the way things were.

Strode’s photos show this acceptance. You can see it in the faces of the steelworkers, covered in soot but looking directly at the camera with a sense of dignity. You can see it in the images of ordinary homes, neatly kept, with a backdrop of industrial haze. These weren’t just pictures of pollution; they were portraits of people navigating a compromised world, finding moments of normalcy and joy in a place that was both their home and their poison.

A Glimmer of Change

By the early 1970s, a new awareness was beginning to dawn. The creation of the EPA in 1970 and the launch of the Documerica project were themselves signs that the government was starting to take the environmental crisis seriously. The first Earth Day had just happened. People were beginning to ask questions. Was this really the only way to live? Did progress have to mean sacrificing the health of the very water that gave the region life?

The photographs taken by William Strode became a powerful part of this new conversation. They provided undeniable, vivid proof of the problem. When people saw his colorful, high-quality images of the toxic water and the smog-filled skies, it was harder to ignore the issue. The pictures showed that pollution wasn’t an abstract concept; it was a daily reality for millions of Americans. It was in the water they drank and the air their children breathed. Strode’s work helped to hold up a mirror to the Ohio Valley, reflecting not just the grime, but also the humanity at stake.

It’s the Belle of LOUISVILLE, not the Belle of LOUISIANA.