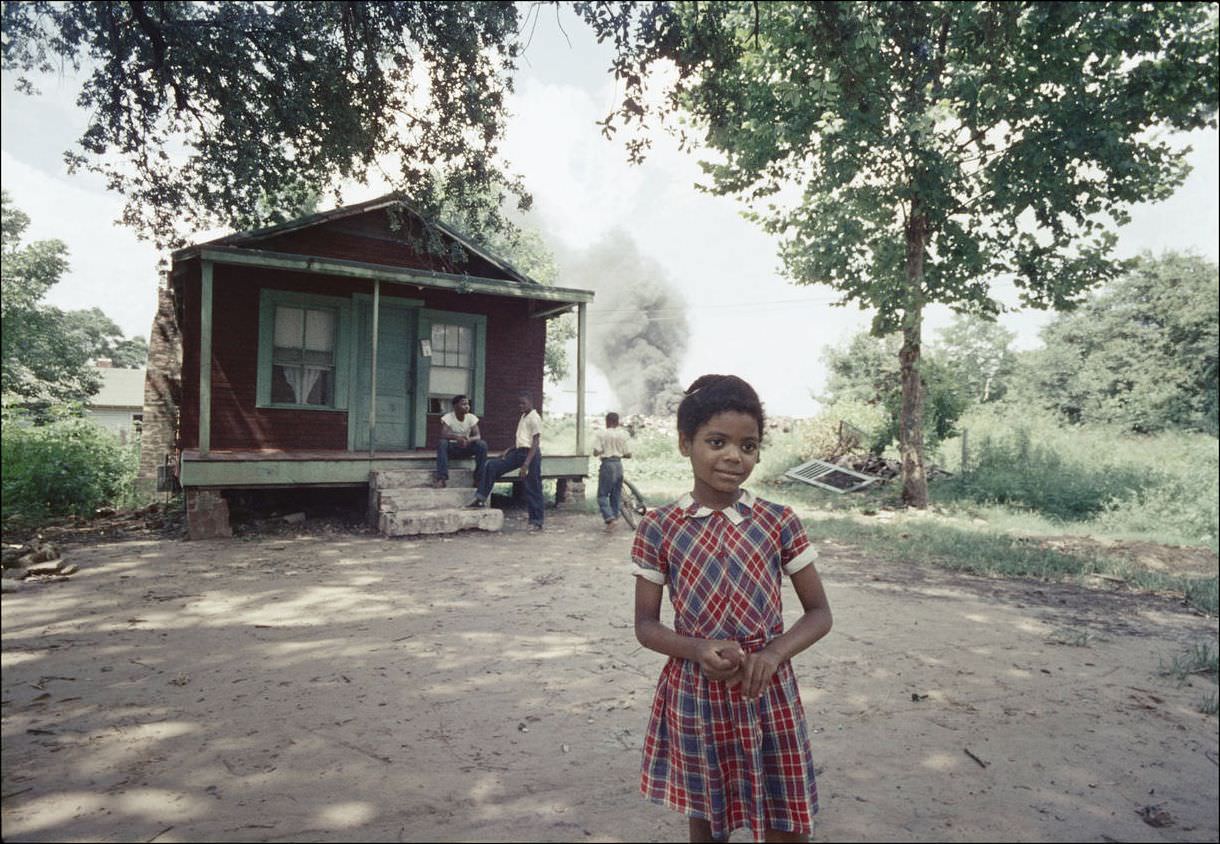

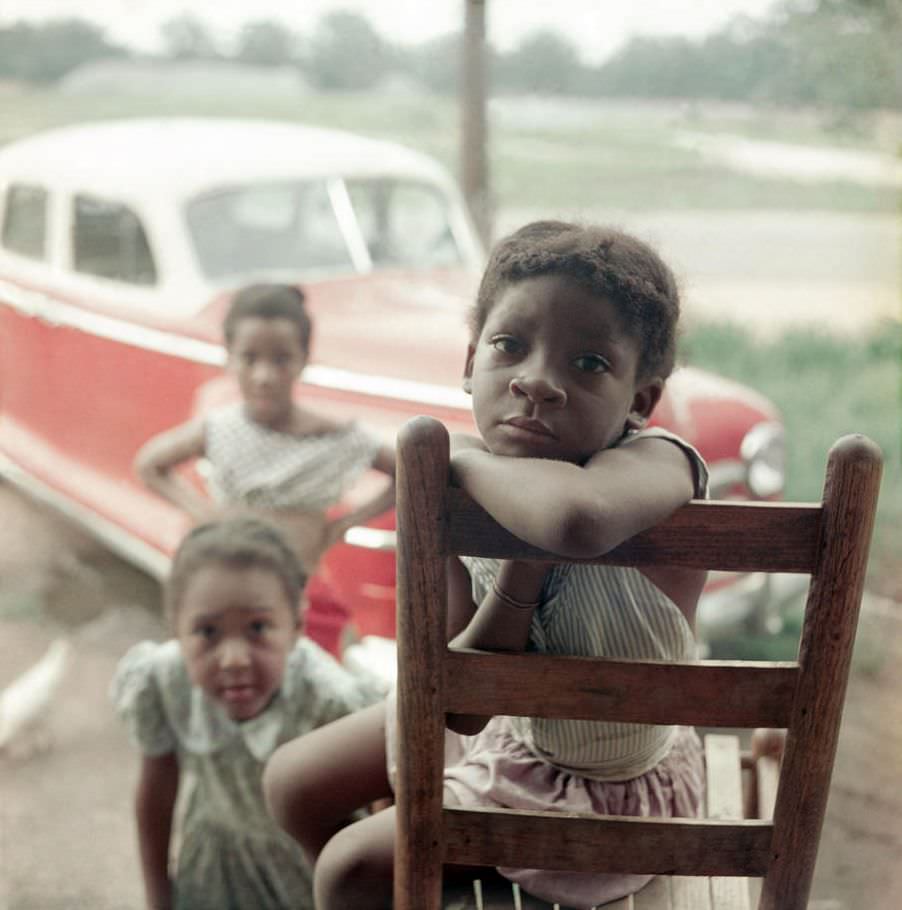

In the 1950s, life in the Southern United States for Black Americans was shaped by a system of laws and customs known as Jim Crow. This system enforced racial segregation, creating two separate and unequal worlds. This reality was documented by photographer Gordon Parks in 1956, when he traveled to Alabama for LIFE magazine. His photographs of the Thornton, Causey, and Tanner families revealed the daily lives of Black families navigating this oppressive environment.

Separate and Unequal by Law

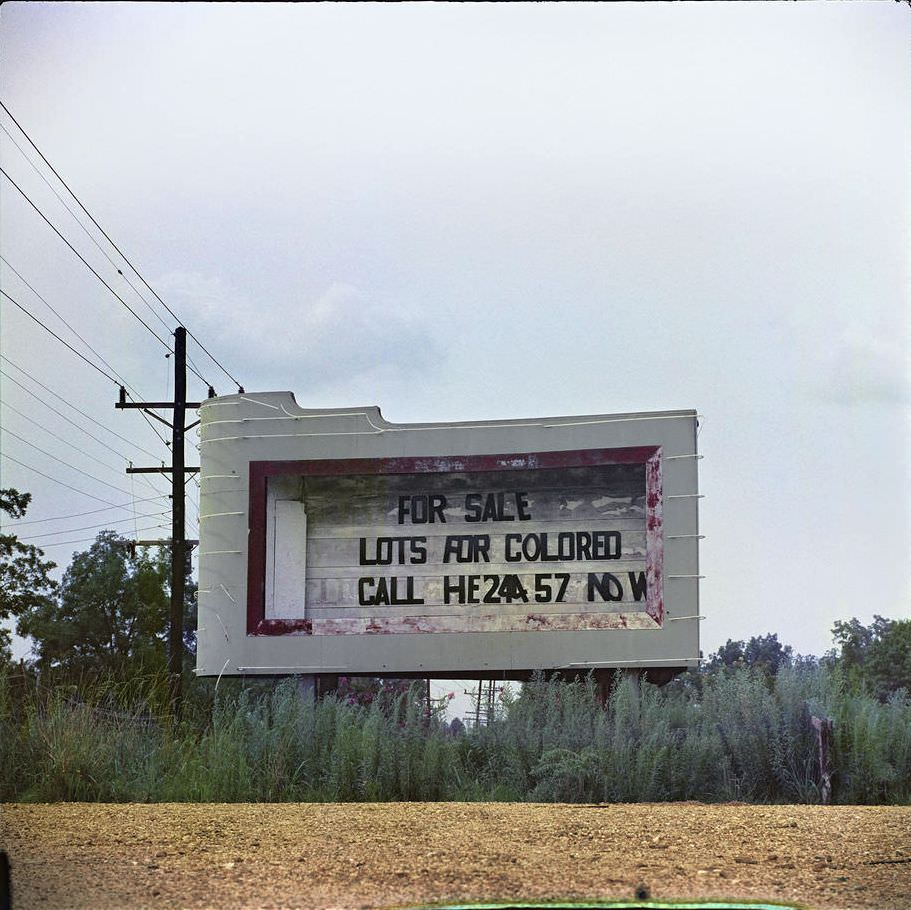

The foundation of segregation was the principle of “separate but equal,” a legal doctrine upheld by the Supreme Court in 1896. In practice, the facilities and services for Black people were consistently inferior to those for white people. In Alabama, Jim Crow laws were extensive. On public buses, Black passengers were required to sit in the back and give up their seats to white passengers if the “white section” was full. All passenger stations for motor transportation had to provide separate waiting rooms and ticket windows for white and colored races.

This separation extended to nearly every aspect of public life. Restaurants were forbidden from serving Black and white customers in the same room unless a solid partition, extending at least seven feet high from the floor, divided them. Hospitals had separate wards, and it was illegal to require a white female nurse to care for a Black male patient. Even in places of leisure, the separation was absolute. It was unlawful for a Black person and a white person to play pool or billiards together..

Read more

Economic Disparity

The economic landscape for Black families in the 1950s South was one of significant inequality. Nationally, the median income for a white family in 1950 was $3,445, while for a non-white family, it was only $1,869. This gap was a result of limited employment opportunities and wage discrimination. The majority of Black men in the South worked in agriculture or as laborers. In 1950, 34.2% of Black males in the South were employed in agriculture, compared to 21.3% of white males.

In non-farm sectors, Black workers were often confined to the lowest-paying and most physically demanding jobs. They were underrepresented in white-collar professions. In 1950, only 5.5% of Black men in the South held white-collar jobs, compared to 16% of white men. This disparity was reinforced by a lack of access to quality education and training.

Education Under Segregation

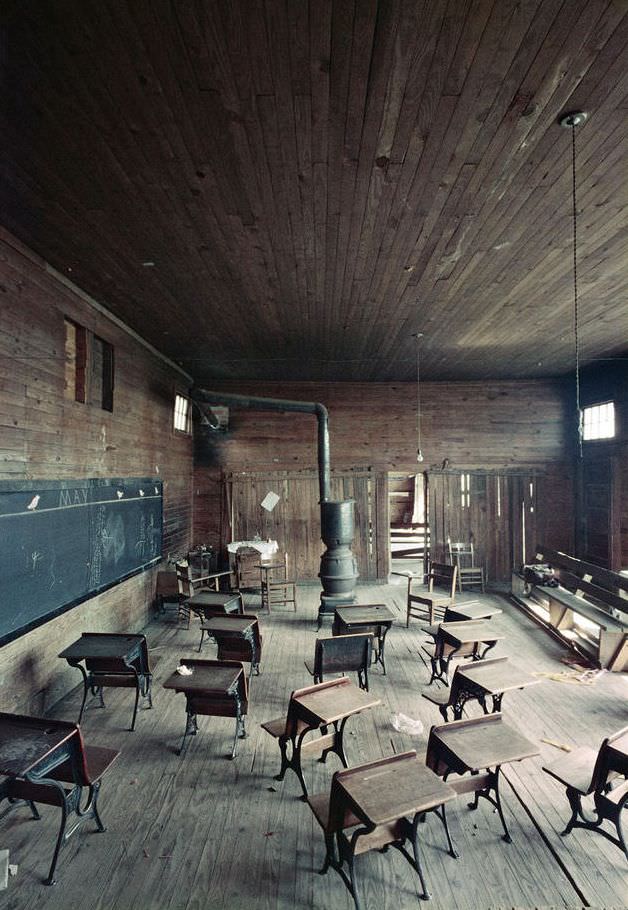

Public schools in the South were segregated by race, and the resources allocated to them were starkly different. In the 1951-1952 school year in Alabama, the average salary for an instructional staff member in a white school was significantly higher than for their counterpart in a Black school. This funding disparity resulted in overcrowded classrooms, dilapidated buildings, and a lack of basic supplies for Black students. Black schools often had to make do with secondhand textbooks and equipment from white schools.

The journey to school itself highlighted the inequality. While bus transportation was often provided for white students, Black students frequently had to walk miles to get to their schools, regardless of the weather. These conditions were intended to limit the educational attainment of Black children and, by extension, their future opportunities.

Health and Wellbeing

The inequalities of the segregated South had a direct impact on the health and well-being of Black families. In 1950, the infant mortality rate for white infants in the United States was 26.8 deaths per 1,000 live births. For Black infants, that number was 43.9 deaths per 1,000 live births, a reflection of inadequate prenatal care, nutrition, and hospital facilities for Black mothers.

Hospitals were segregated, and in many places, Black patients were denied access to specialized medical care available to whites. The living conditions for many Black families, often characterized by substandard housing without adequate sanitation, also contributed to poorer health outcomes.

The Right to Vote

The political voice of Black citizens in the 1950s South was systematically suppressed. Although the 15th Amendment to the Constitution had granted Black men the right to vote, Southern states used various methods to disenfranchise them. These included poll taxes, literacy tests that were subjectively administered, and intimidation.

As a result, voter registration rates among Black Americans were extremely low. In 1950s Alabama, only about 19.4% of eligible Black citizens were registered to vote. In neighboring Mississippi, the situation was even more dire, with only 6.4% of eligible Black voters on the rolls. This lack of political power made it impossible to challenge the discriminatory laws and practices of the Jim Crow system through the democratic process. The daily lives of the Thornton, Causey, and Tanner families, as captured by Gordon Parks, showed the human reality behind these statistics, a life of resilience in the face of legally enforced inequality.