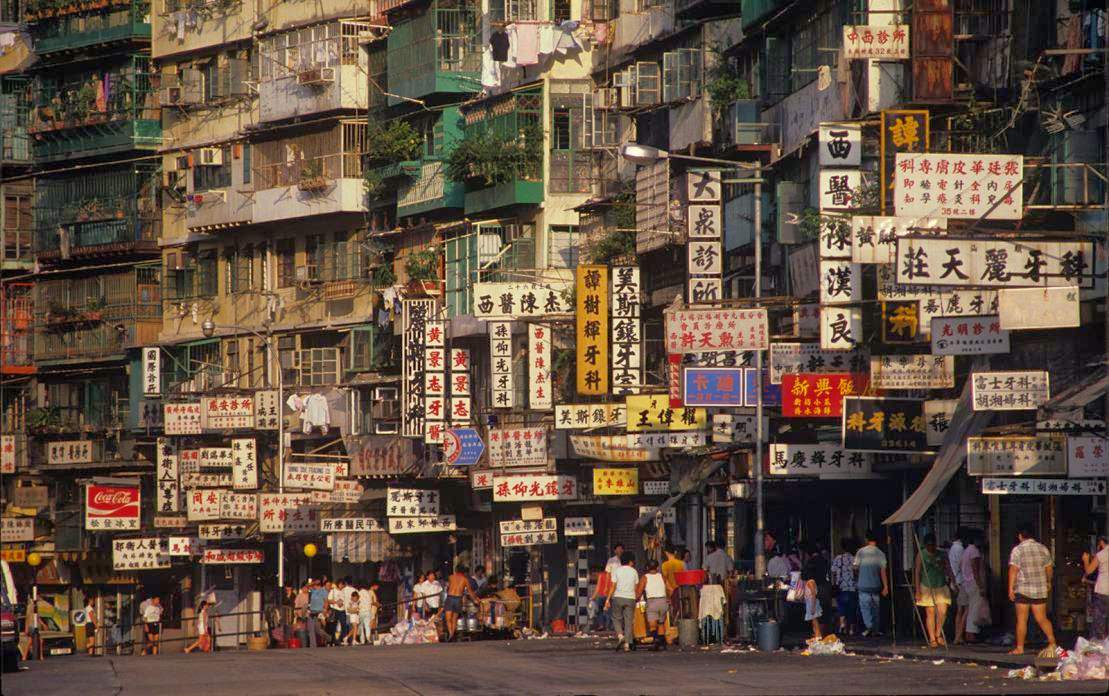

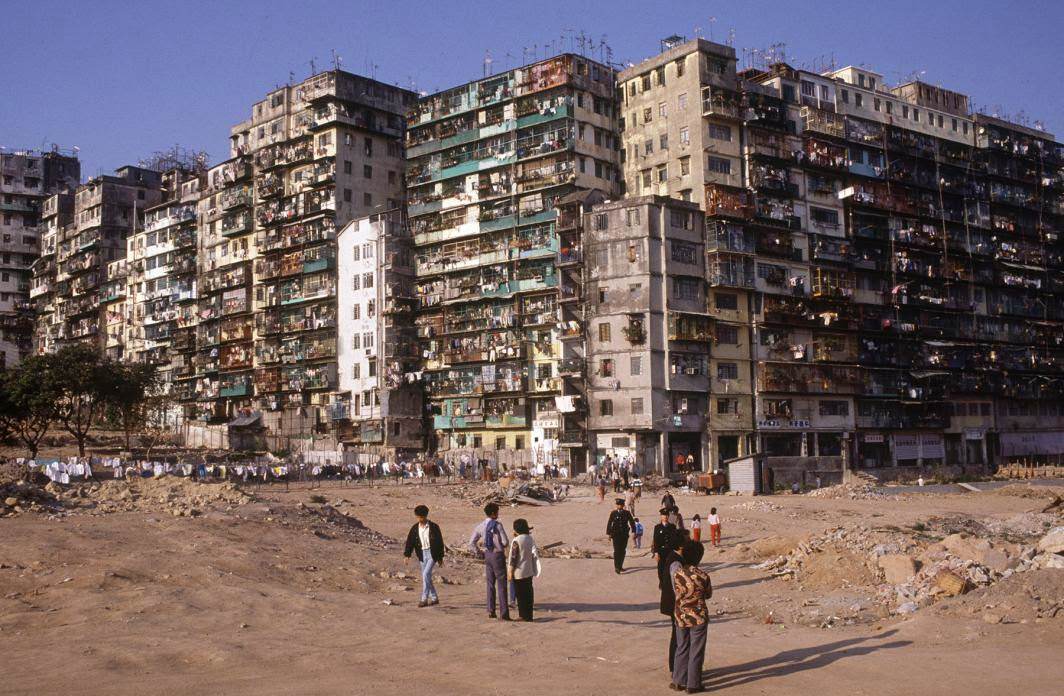

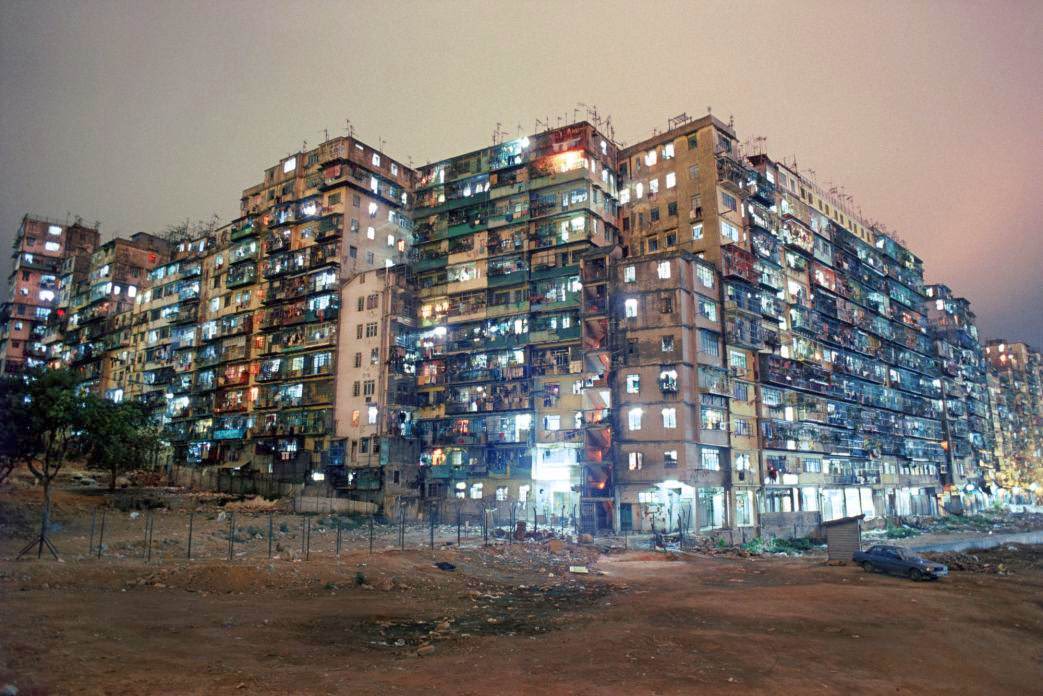

In the 1980s, Hong Kong was home to one of the most unique urban environments in the world: the Kowloon Walled City. It was a massive, densely packed settlement that operated largely outside of government control. Within a single city block, over 30,000 people lived and worked in a complex of more than 300 interconnected high-rise buildings, all constructed without the involvement of a single architect.

A City Within a City

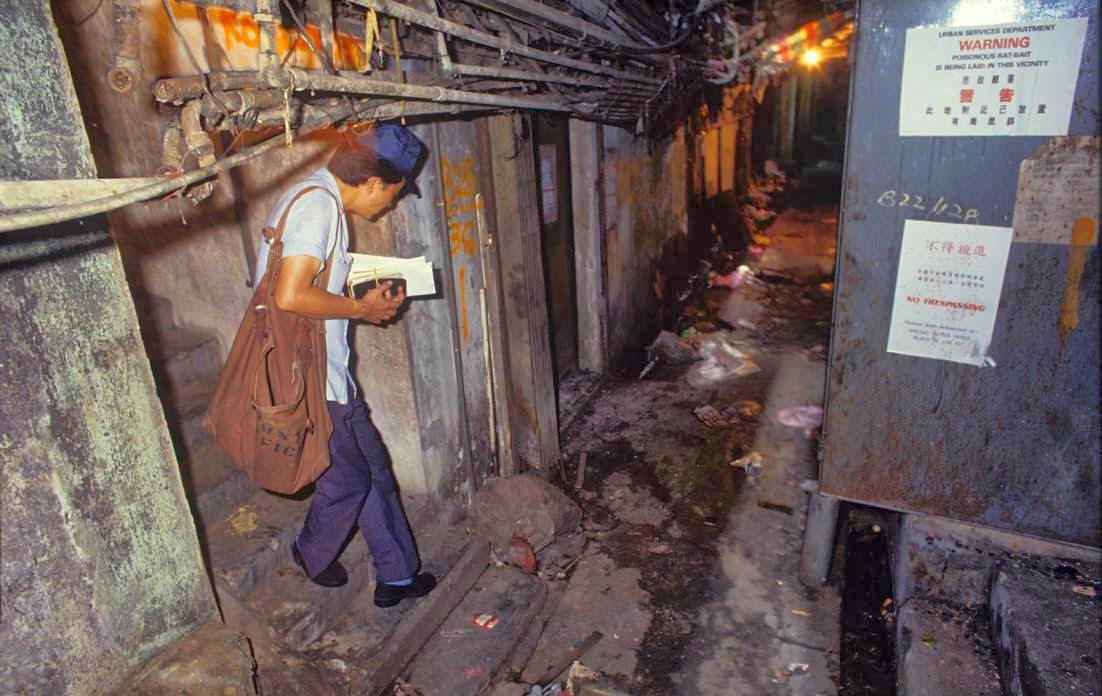

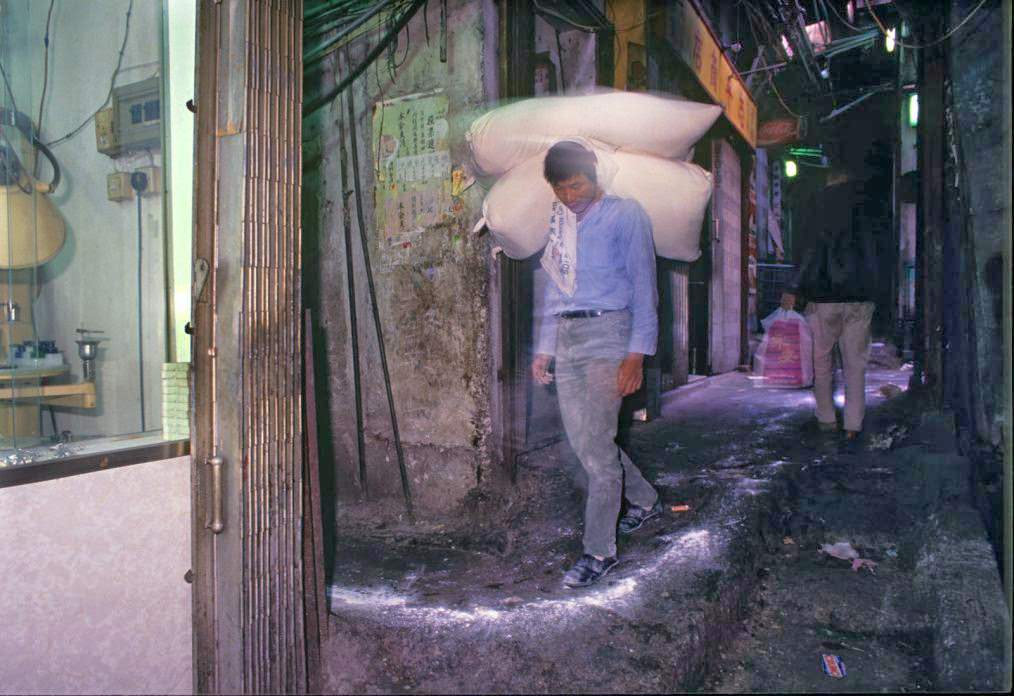

The Walled City’s unusual status stemmed from a historical loophole that left it in a state of legal ambiguity, largely ungoverned by British Hong Kong authorities. This lack of oversight allowed it to grow organically and chaotically. Buildings were constructed on top of and alongside each other, rising up to 14 stories high. This dense construction created a maze of narrow, dark alleyways, some only a few feet wide. Sunlight rarely reached the lower levels, which were in a state of perpetual twilight, illuminated by a tangle of fluorescent lights and bare bulbs.

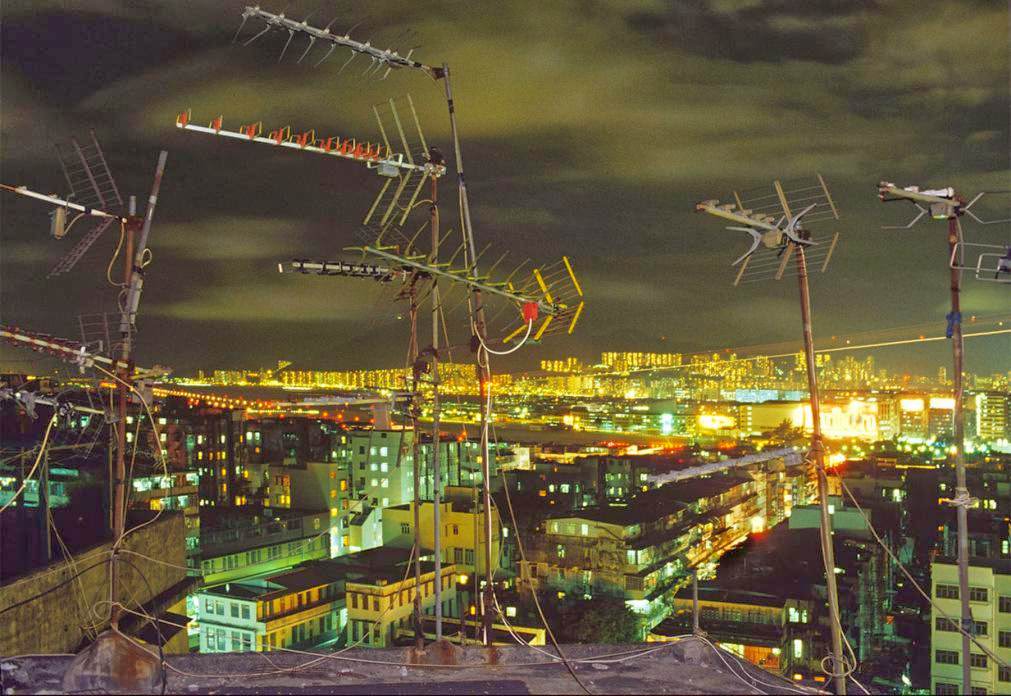

The infrastructure was a makeshift creation of the residents. A web of exposed pipes carried water throughout the complex, often leaking onto the paths below. Electricity was drawn from the main Hong Kong grid, but the wiring within the city was a chaotic and hazardous network strung from wall to wall. There was no organized garbage collection, so trash was often thrown onto the central rooftops or into air shafts.

Read more

Daily Life and Commerce

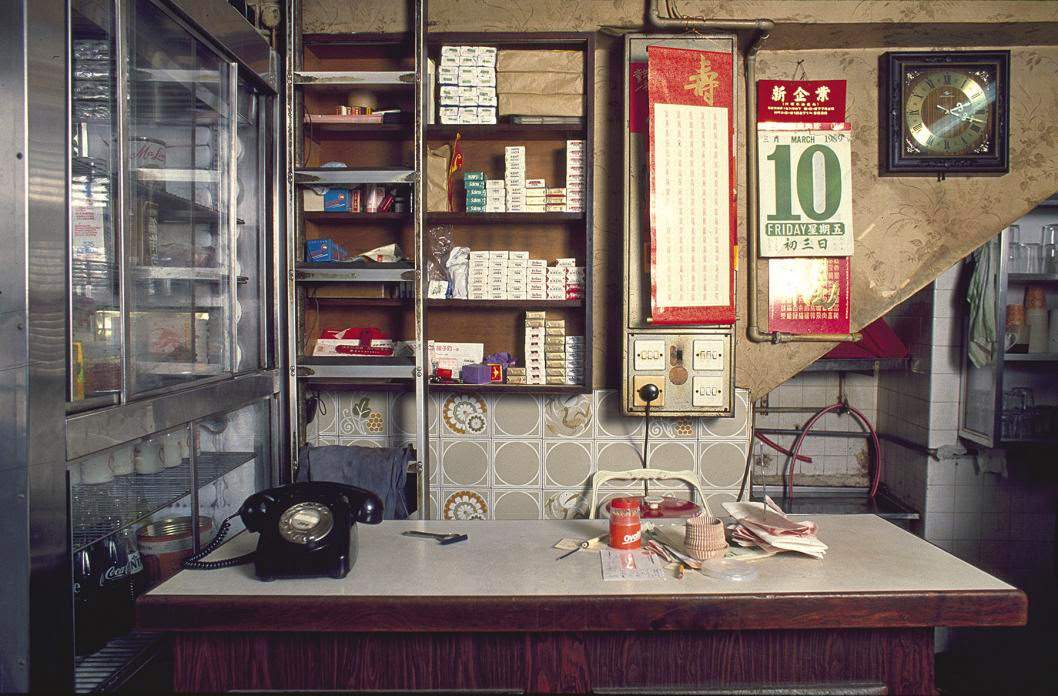

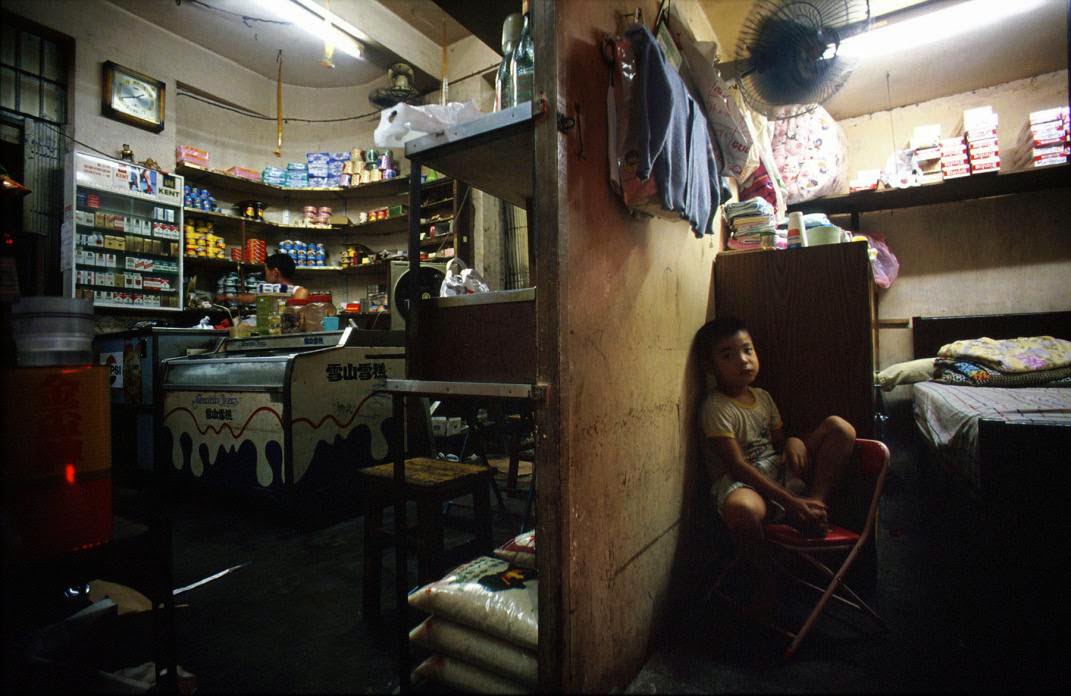

Despite its anarchic appearance, the Walled City was a functioning community with a vibrant internal economy. The ground floors of the buildings were filled with a variety of small businesses. Because government licenses were not required, many doctors and dentists who were not permitted to practice in the rest of Hong Kong set up their clinics there, offering affordable care to residents.

Small factories operated throughout the city, producing goods like fish balls, noodles, and textiles. There were also numerous grocery stores, barbershops, and small restaurants that catered to the local population. The city was a hub of activity at all hours, with the sounds of mahjong tiles, factory machinery, and daily commerce echoing through its narrow corridors.

A Vertical Community

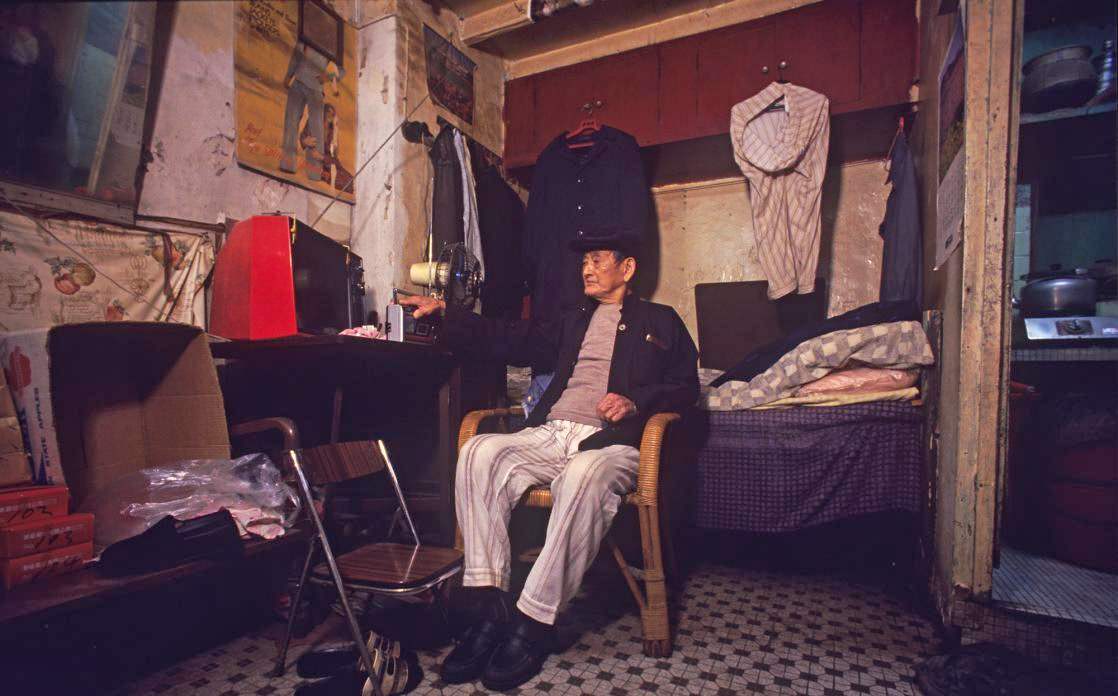

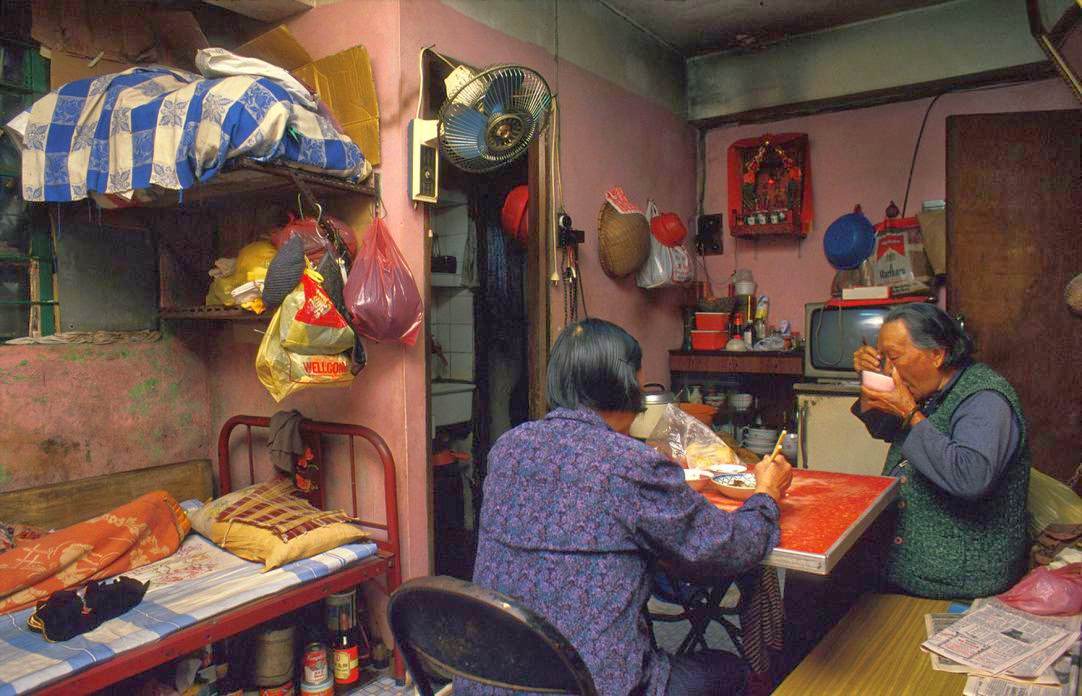

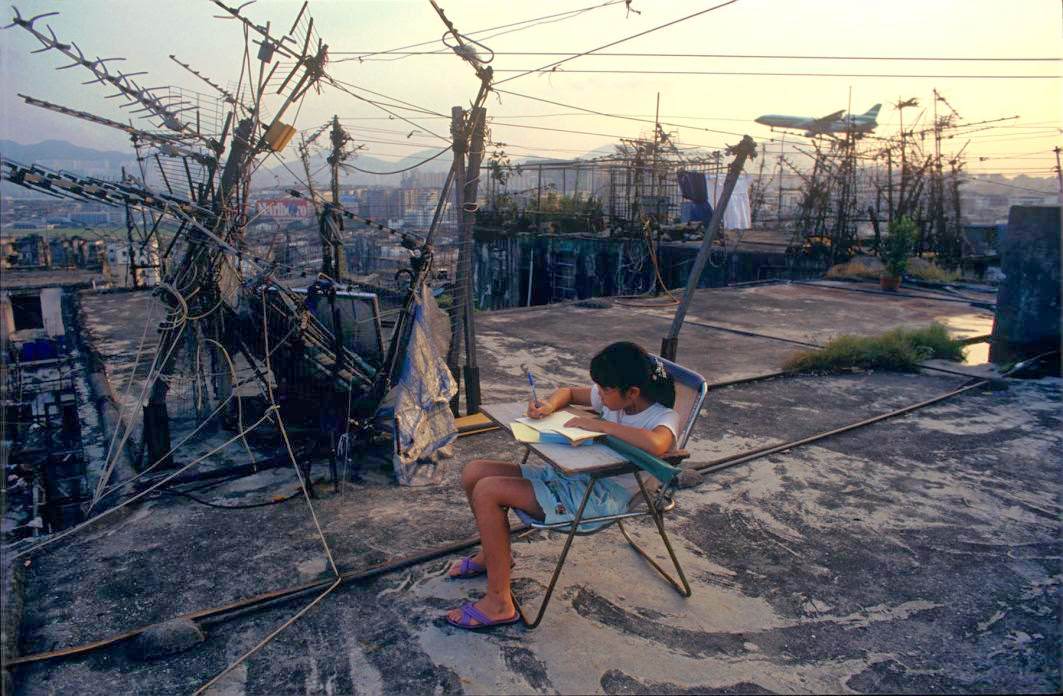

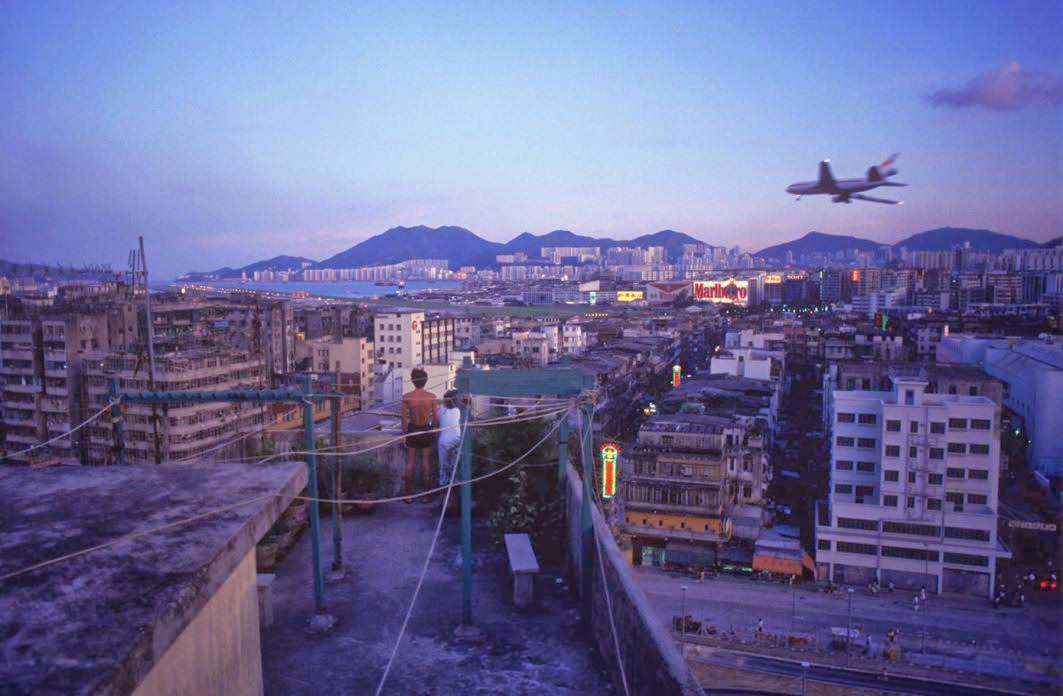

Living spaces within the Walled City were extremely small, with the average apartment being just a few hundred square feet. Families adapted to these cramped conditions with ingenuity, building lofts for sleeping and using every available inch of space. Life was lived vertically; children played on the rooftops, which formed a sort of elevated, cluttered playground high above the city streets. This was often the only place to get fresh air and sunlight.

The residents developed a strong sense of community and self-reliance. Resident associations helped to resolve disputes and organize basic services. While the city had a reputation as a haven for criminal activity run by Triad gangs, for the majority of its residents, it was simply an affordable place to live and work. Photographers like Greg Girard and Ian Lambot, who spent years documenting the city before its demolition in 1992, captured this complex reality, showing a community that thrived against all odds.