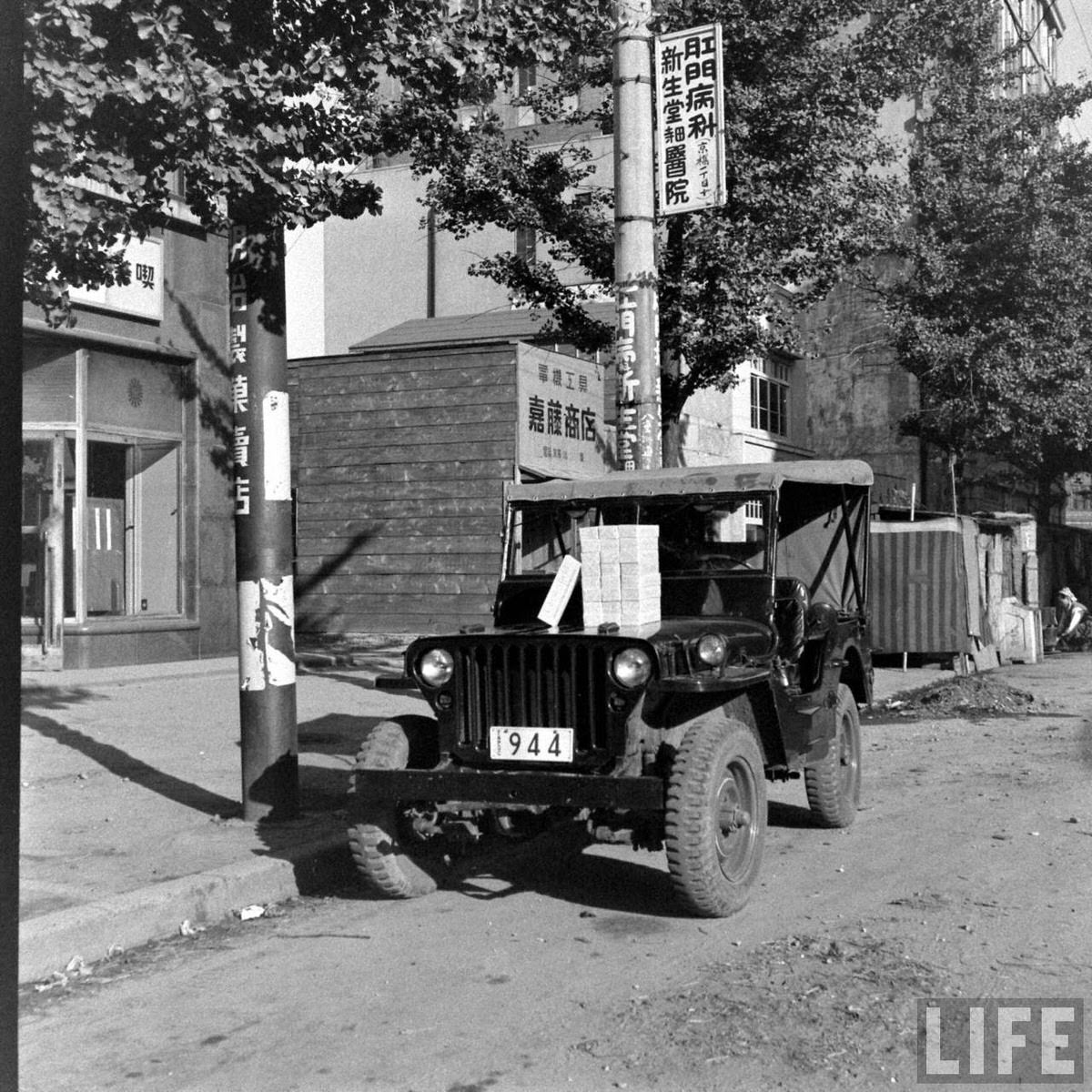

Following the surrender of Japan, the official economy collapsed completely. Government ration distribution systems failed to deliver enough food, leaving the population facing starvation. In this vacuum, yami-ichi, or black markets, appeared almost overnight. These were not hidden in back alleys; they were open-air bazaars located near major transport hubs. The Ozu gang was the first to organize on a large scale. Just four days after the war ended, they placed advertisements in newspapers asking factory owners to bring their goods to them instead of the military.

The Lights of Shinjuku

The Ozu gang established a massive market near Shinjuku Station in Tokyo. By late 1945 and into 1946, this market dominated the area. To ensure everyone knew where to buy goods, the gang built a massive sign illuminated by 117 hundred-watt bulbs. In a city that was largely destroyed and dark, this sign was visible for miles. It served as a beacon for desperate citizens looking for rice, cooking oil, and soap. Other gangs observed this success and quickly replicated the model, setting up similar markets in Ueno, Ikebukuro, and Osaka.

Read more

The “Peanuts” and the Profits

The vendors who worked the stalls were nicknamed “peanuts.” They stood at the bottom of the criminal hierarchy but earned significantly more than honest professionals. A single vendor in the Shinjuku market took home roughly 50 yen a day. In sharp contrast, a school teacher in 1946 earned a monthly salary of only 300 yen. This massive disparity in income drew thousands of unemployed soldiers and civilians into the underground economy.

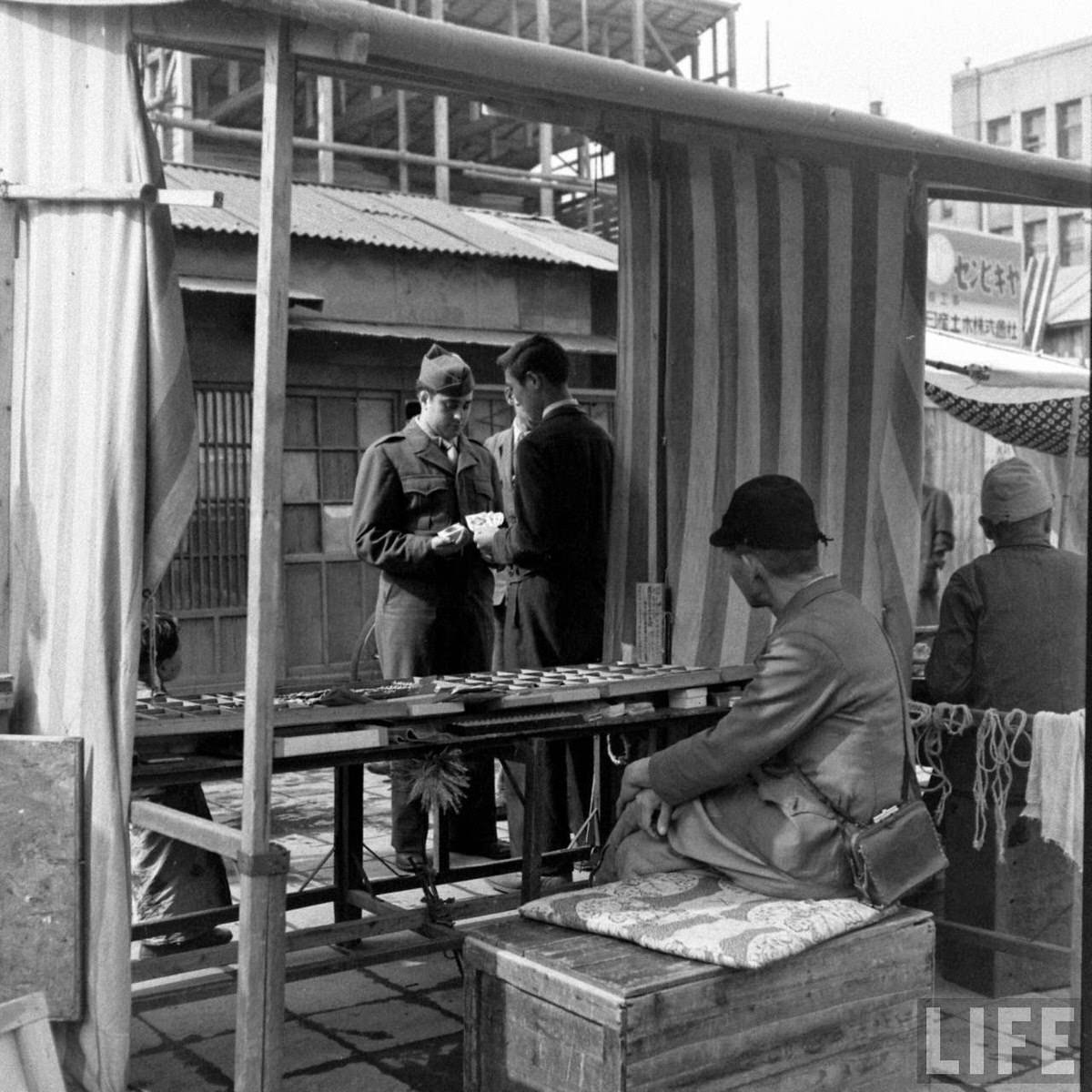

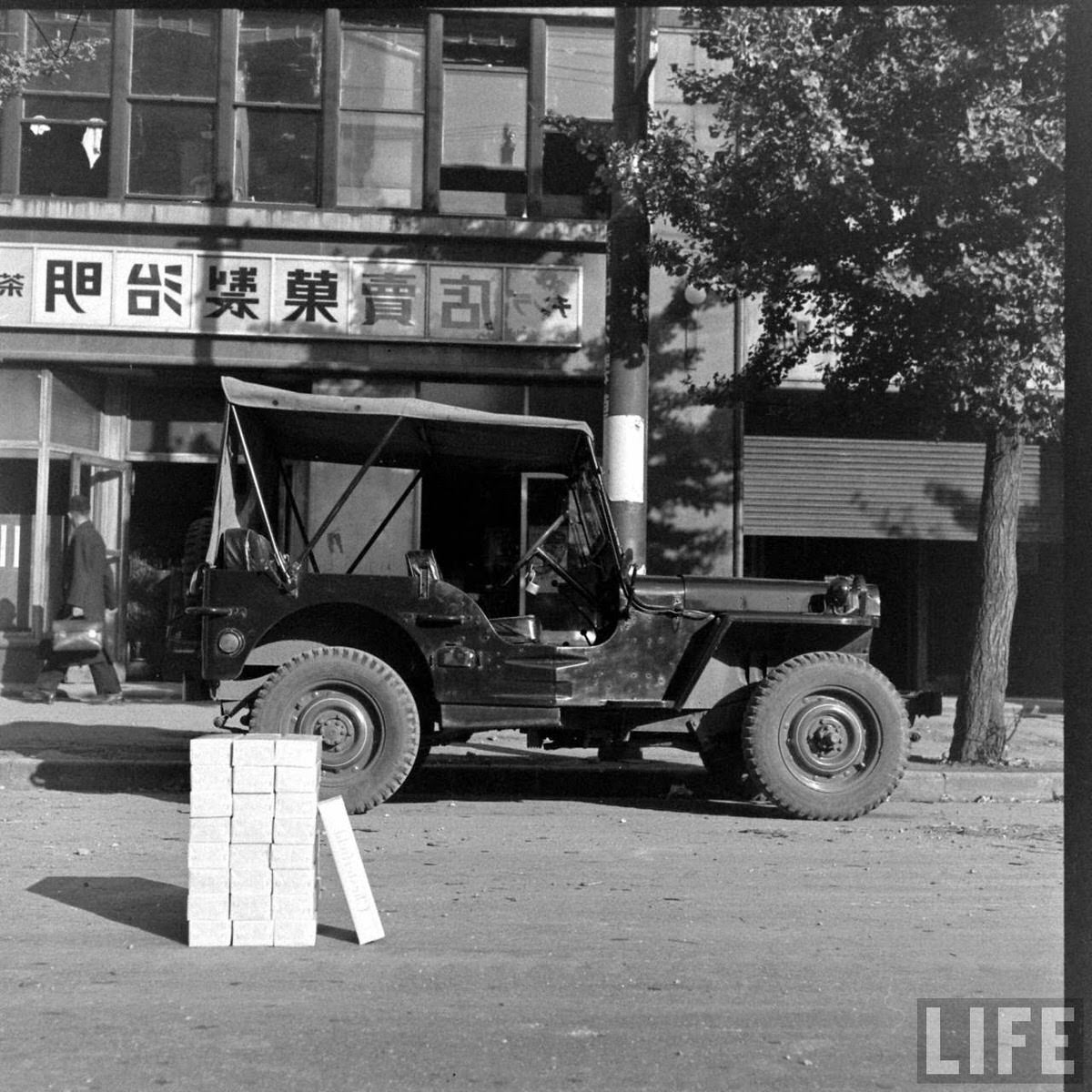

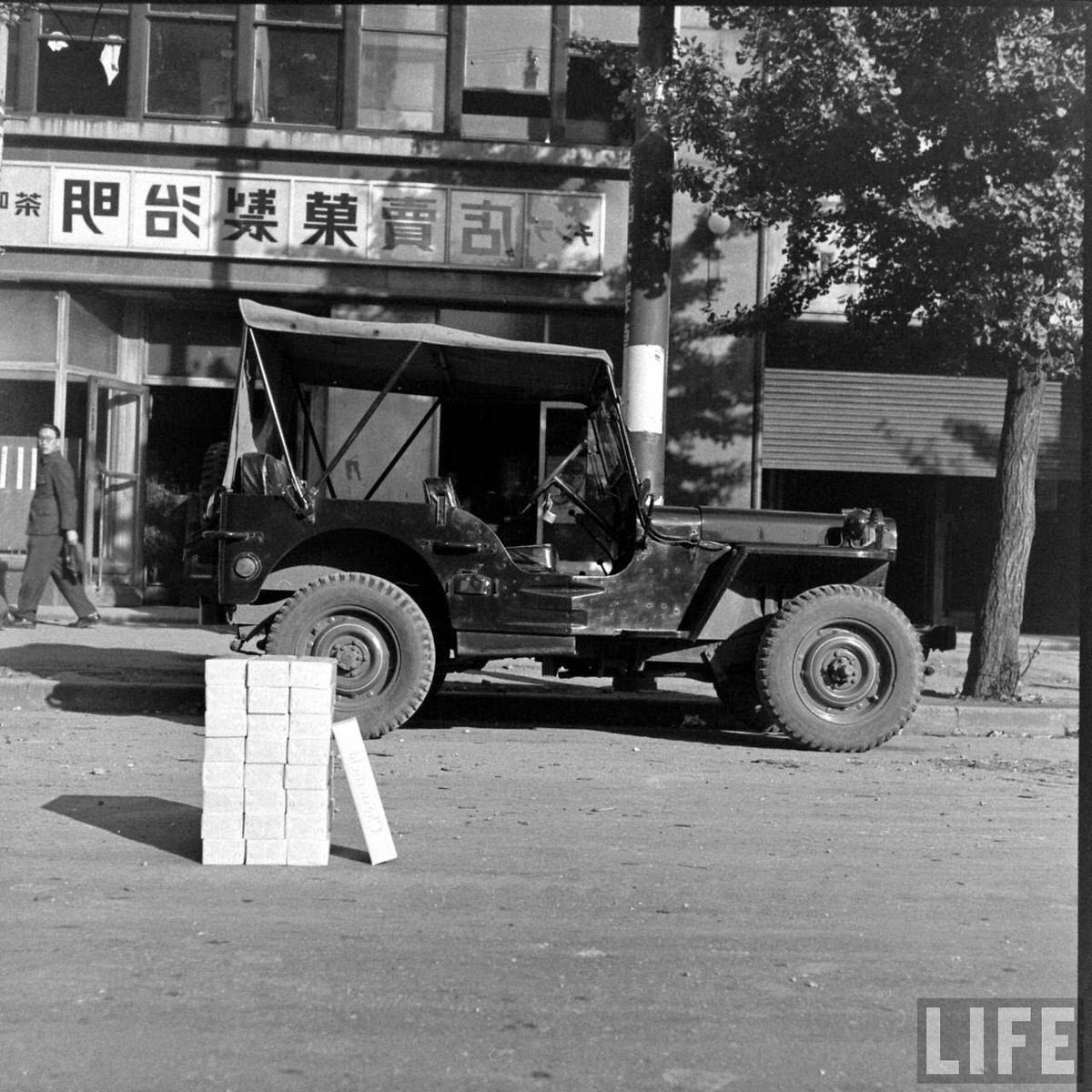

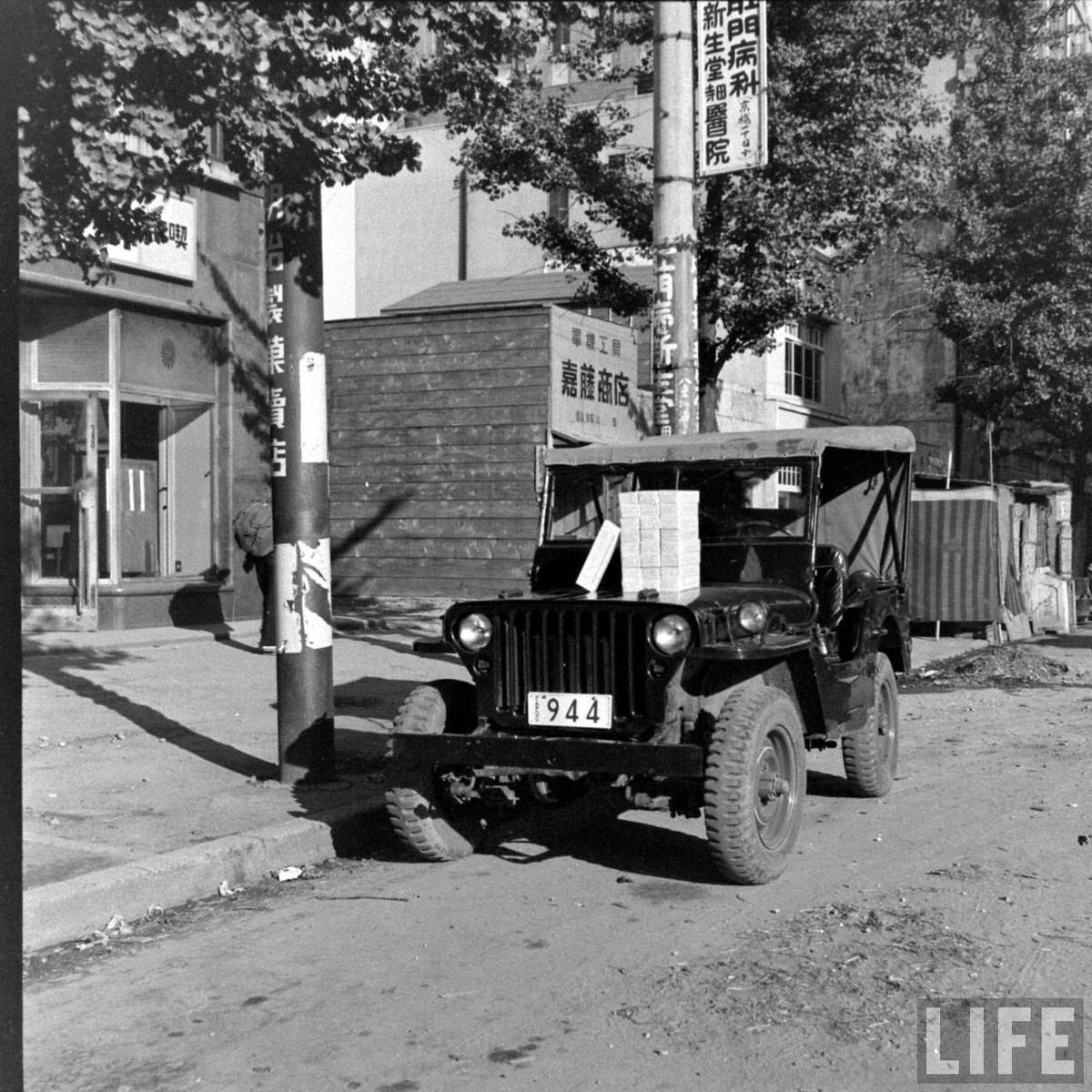

Goods and Sellers

The markets sold a mix of military surplus and diverted factory goods. Canned food, old army uniforms, and blankets were high-value items. About 30% of the workers in these markets were “third-country people,” a term used for Koreans and Taiwanese residents who remained in Japan. They often had better access to supplies and faced different legal treatment than Japanese citizens. Police frequently raided the stalls to confiscate illegal goods, but the markets always reopened the next day.

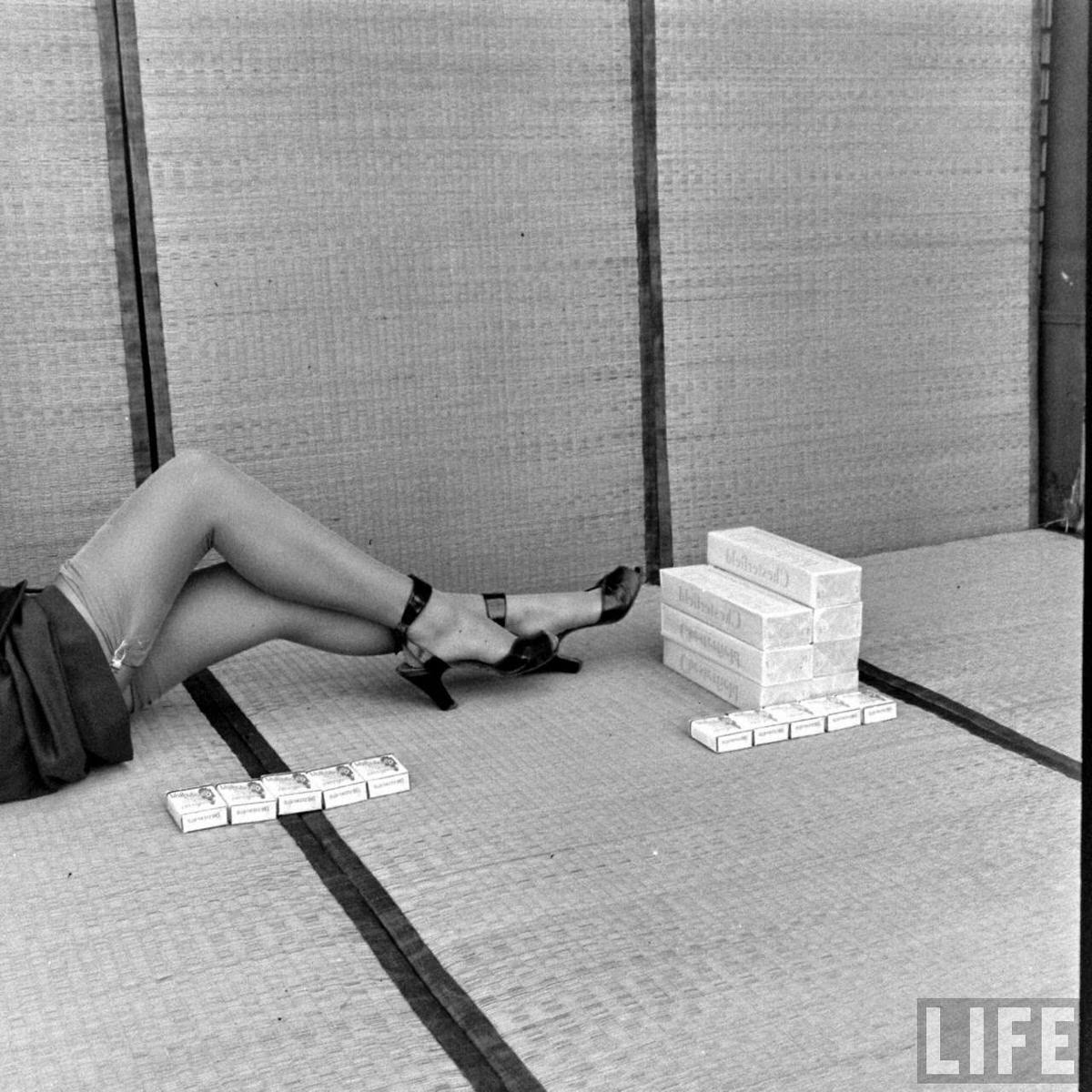

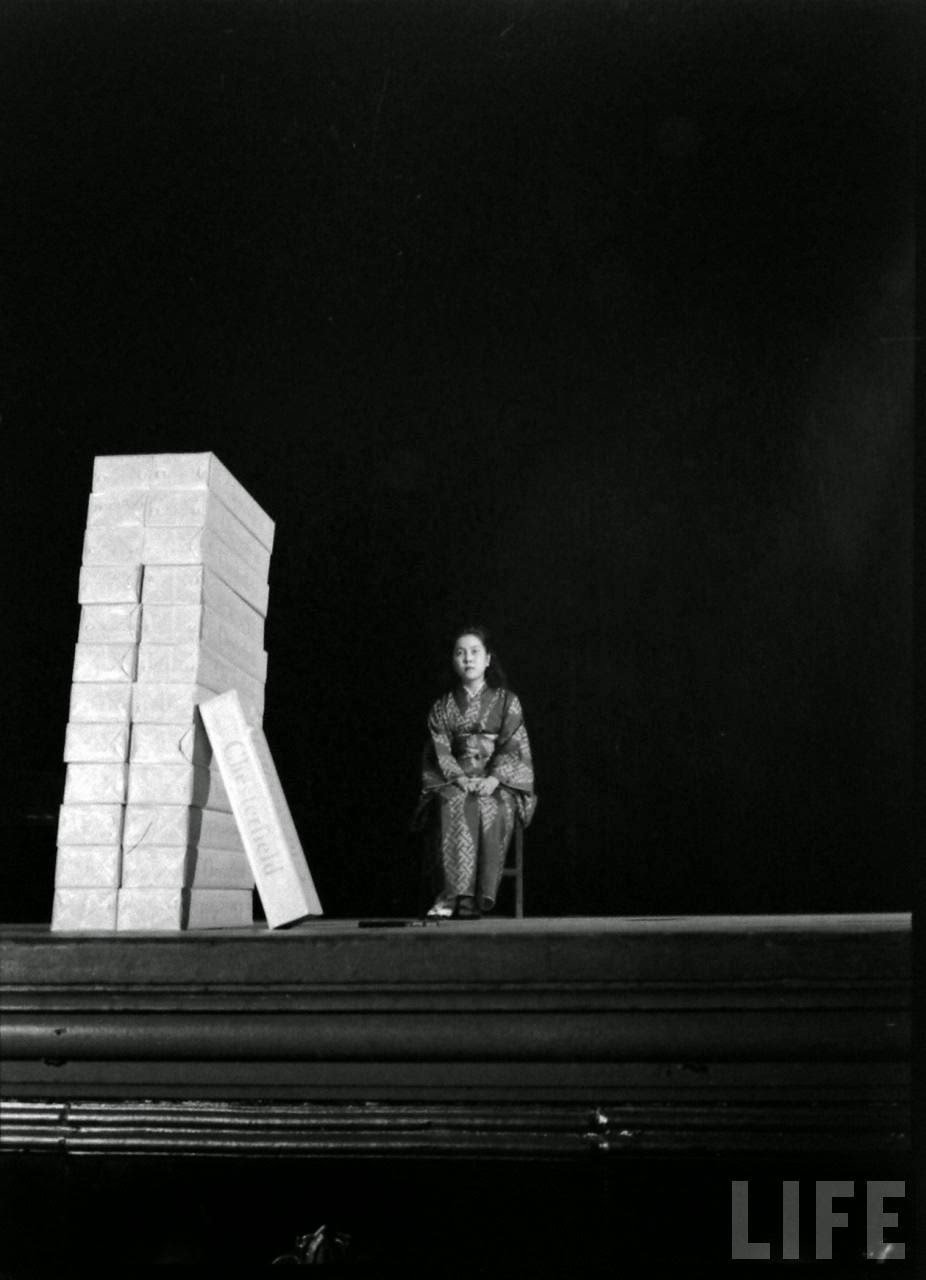

The “Bamboo Shoot” Life

For the customers, the black market was a place of necessity and loss. Inflation was rampant, and prices changed by the hour. Families lived what was called a “bamboo shoot existence.” Like peeling the layers off a bamboo shoot, they sold their possessions one by one to pay for food. They traded fine silk kimonos, heirlooms, and furniture for small amounts of white rice or sweet potatoes. Without the black market, many urban residents would have starved, but participating in it cost them their life savings.