During the Second World War, the cold, metal skins of military aircraft were transformed into personal canvases. Aircrews painted designs, names, and characters on the fuselages of their planes, creating a unique form of folk art known as nose art. This practice served as a way to boost morale, bring good luck, and give a touch of identity to the anonymous machinery of war.

From Magazine Pages to Painted Designs

The tradition began simply. In the early years of the war, before painting directly on the aircraft became common, crews of the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) would paste pin-up pictures from popular magazines onto their planes. Pages torn from publications like Esquire or Look were glued onto the nose, fuselage, or tail sections of bombers like the B-17 Flying Fortress. These images served as reminders of home and as good luck charms.

As the war progressed, this simple practice evolved into a more elaborate art form. Crews began to commission artists to paint original designs directly onto the aircraft. These artists were often talented servicemen within the squadron or, in some cases, professional civilian artists hired for the job. By the end of the war, the demand was so high that artists could earn up to $15 per aircraft for their work.

Read more

Common Themes and Famous Examples

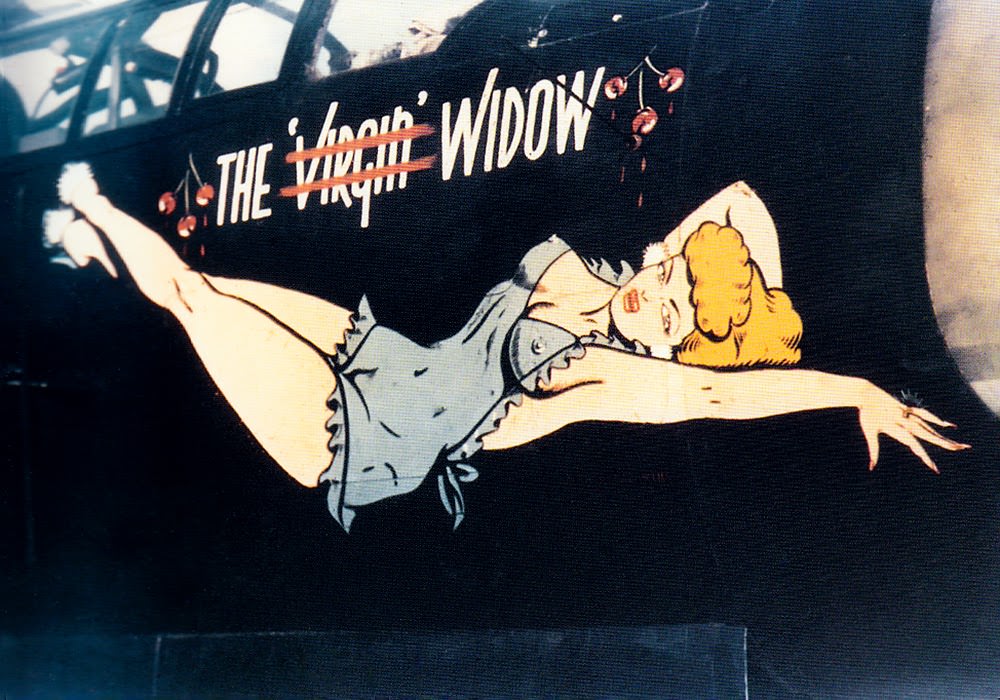

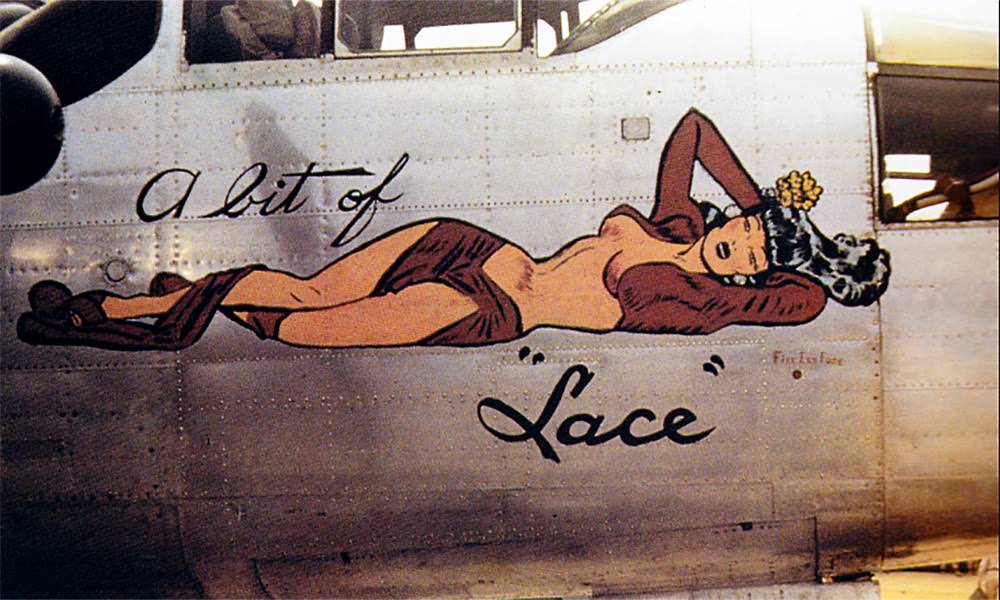

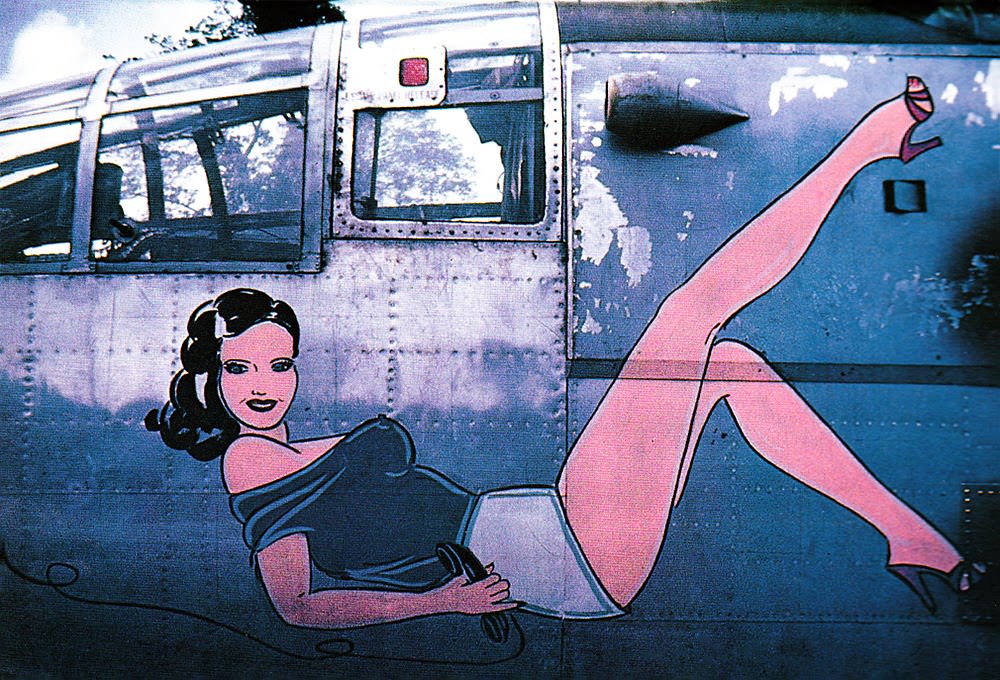

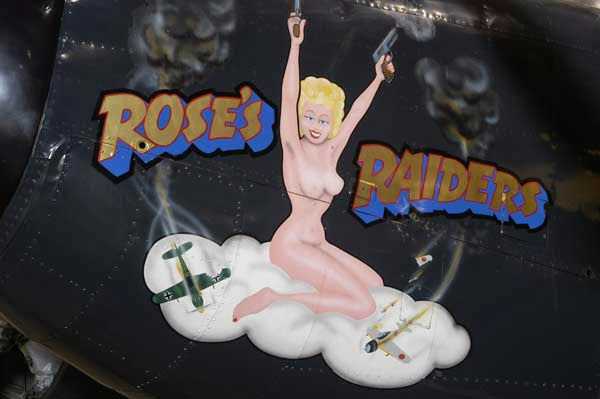

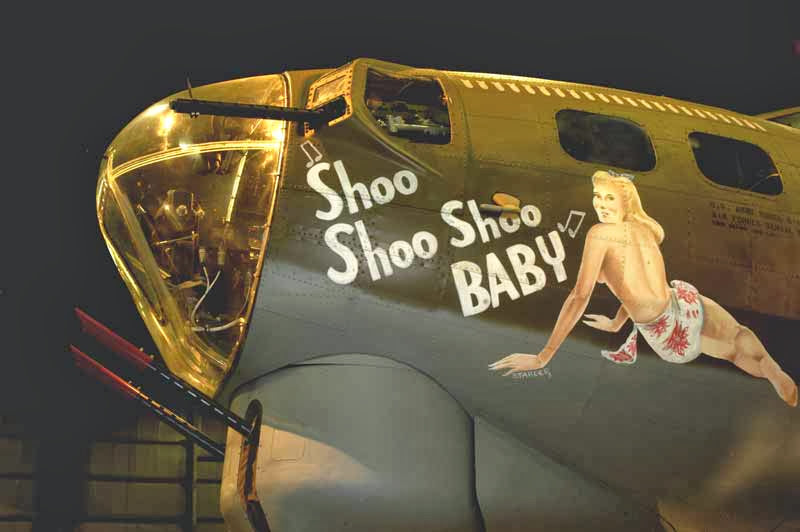

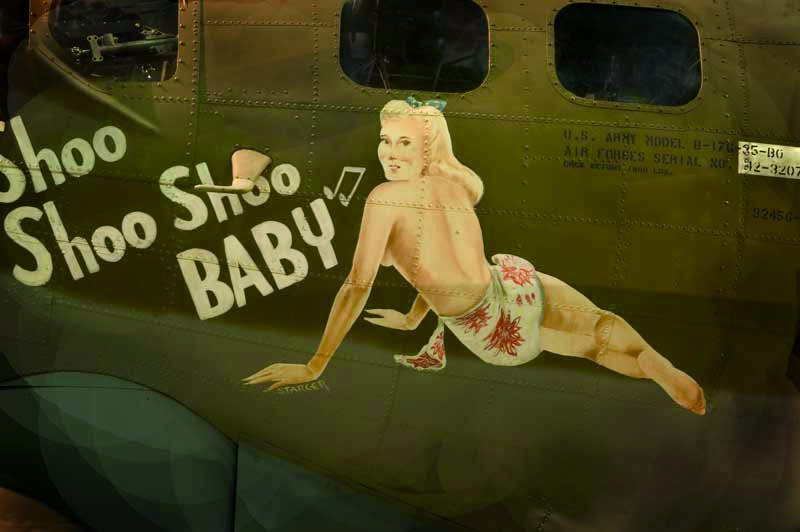

The subjects of WWII nose art were varied, but several key themes were especially popular. Pin-up girls were by far the most common subject. These idealized images of women, often depicted in playful or glamorous poses, were a comforting reminder of the girlfriends, wives, and movie stars the servicemen had left behind. The famous B-17 bomber “Memphis Belle,” named after the pilot’s sweetheart, featured a stylized drawing of a woman in a swimsuit on each side of its nose.

Patriotic themes were also widespread. Eagles, American flags, and other national symbols were painted on planes to express pride and determination. Cartoon characters were another favorite, with figures like Bugs Bunny, Donald Duck, and Popeye often shown in military gear or engaging in combat with the enemy. These humorous images brought a moment of lightheartedness to the serious business of war.

Each piece of nose art was directly linked to the aircraft’s unofficial name. A plane might be named after a song, a hometown, or an inside joke among the crew. For example, the B-29 Superfortress that dropped the first atomic bomb was named “Enola Gay” after the pilot’s mother. This naming and decorating process helped the crew form a bond with their machine, turning it from a piece of government property into “their” plane.

Regulations and Regional Differences

Official military regulations regarding nose art were inconsistent. While not officially sanctioned, commanders often tolerated the practice because they recognized its positive effect on morale. The acceptability of the artwork’s content, particularly the pin-up girls, varied depending on the commanding officer and the theater of war. In the European Theater, restrictions were sometimes tighter, while crews in the Pacific often had more freedom with their designs. The art flourished as a form of personal expression in a highly regimented environment, giving a human face to the massive air campaigns of the war.