When World War I began in 1914, millions of men across Europe and later the United States left their jobs to enlist in the armed forces. This created a massive labor shortage on the home front, threatening to cripple industries vital to the war effort. In response, women entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers, taking on demanding and often dangerous jobs that had previously been reserved for men.

The Munitionettes and the Dangers of the Factory

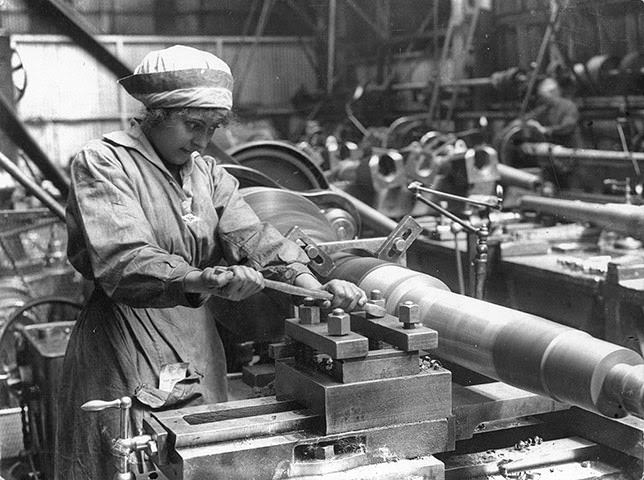

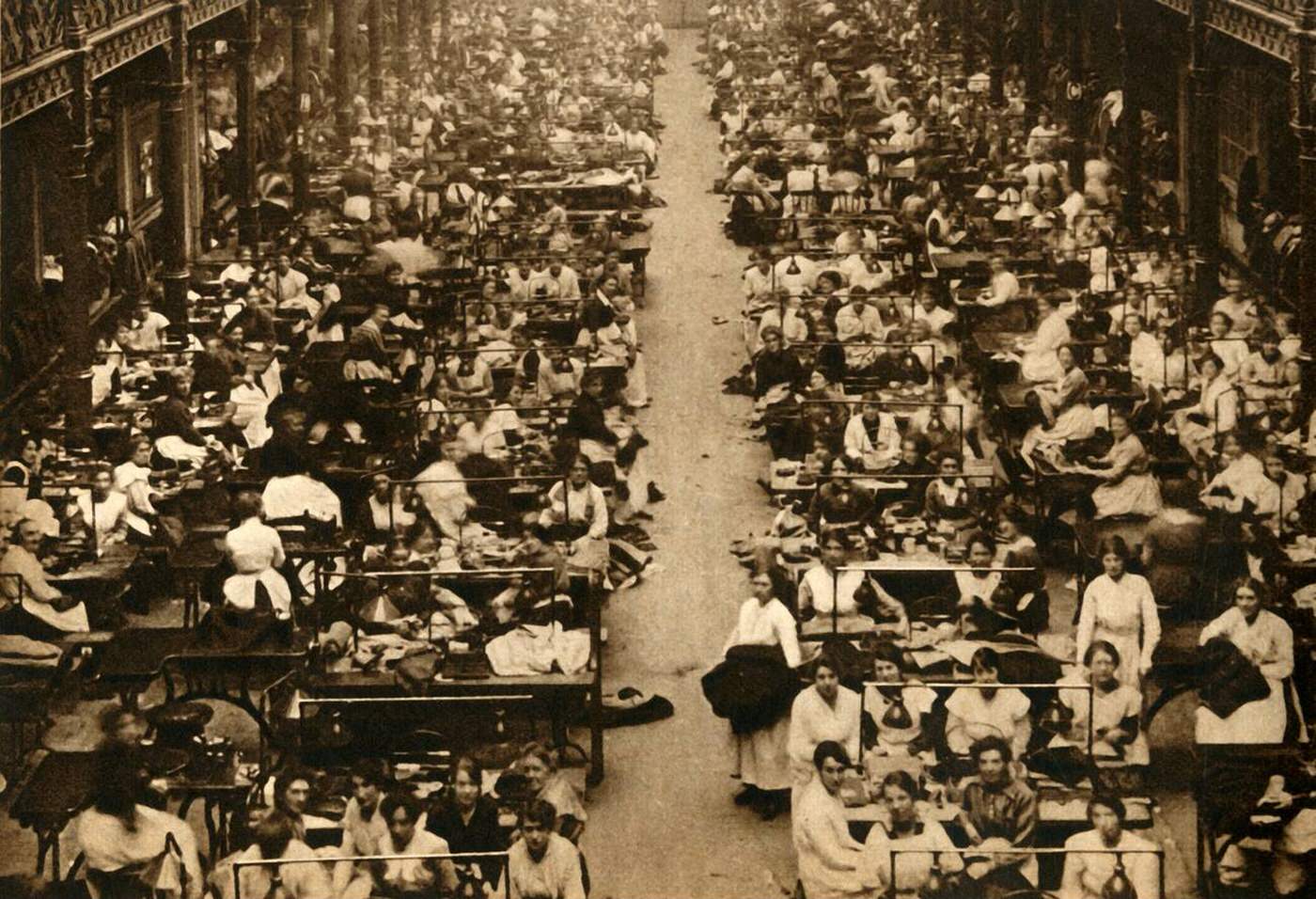

The greatest demand for female labor was in munitions factories. In Britain alone, nearly one million women worked in munitions by 1918. These women, known as “munitionettes,” manufactured the shells and bullets essential for the soldiers at the front. The work was repetitive and physically demanding, but it was also incredibly dangerous.

Workers handled hazardous chemicals daily, including trinitrotoluene (TNT). Constant contact with TNT caused a serious condition called toxic jaundice, which turned the skin a bright yellow color. This earned the women the nickname “Canary Girls.” While the yellow tint often faded after a worker left the factory, the chemical exposure could lead to long-term liver damage and other health problems. During the war, there were 400 recorded cases of toxic jaundice, which proved fatal for about a quarter of those affected.

Read more

The risk of explosions was a constant threat. In January 1917, a blast at a chemical factory in Silvertown, London, killed 73 people. An explosion at the National Shell Filling Factory in Chilwell, Nottinghamshire, in July 1918, killed 134 workers. Despite these dangers, women continued to work in the factories, often motivated by patriotism and the lure of wages that were higher than those in traditional domestic service.

The Women’s Land Army

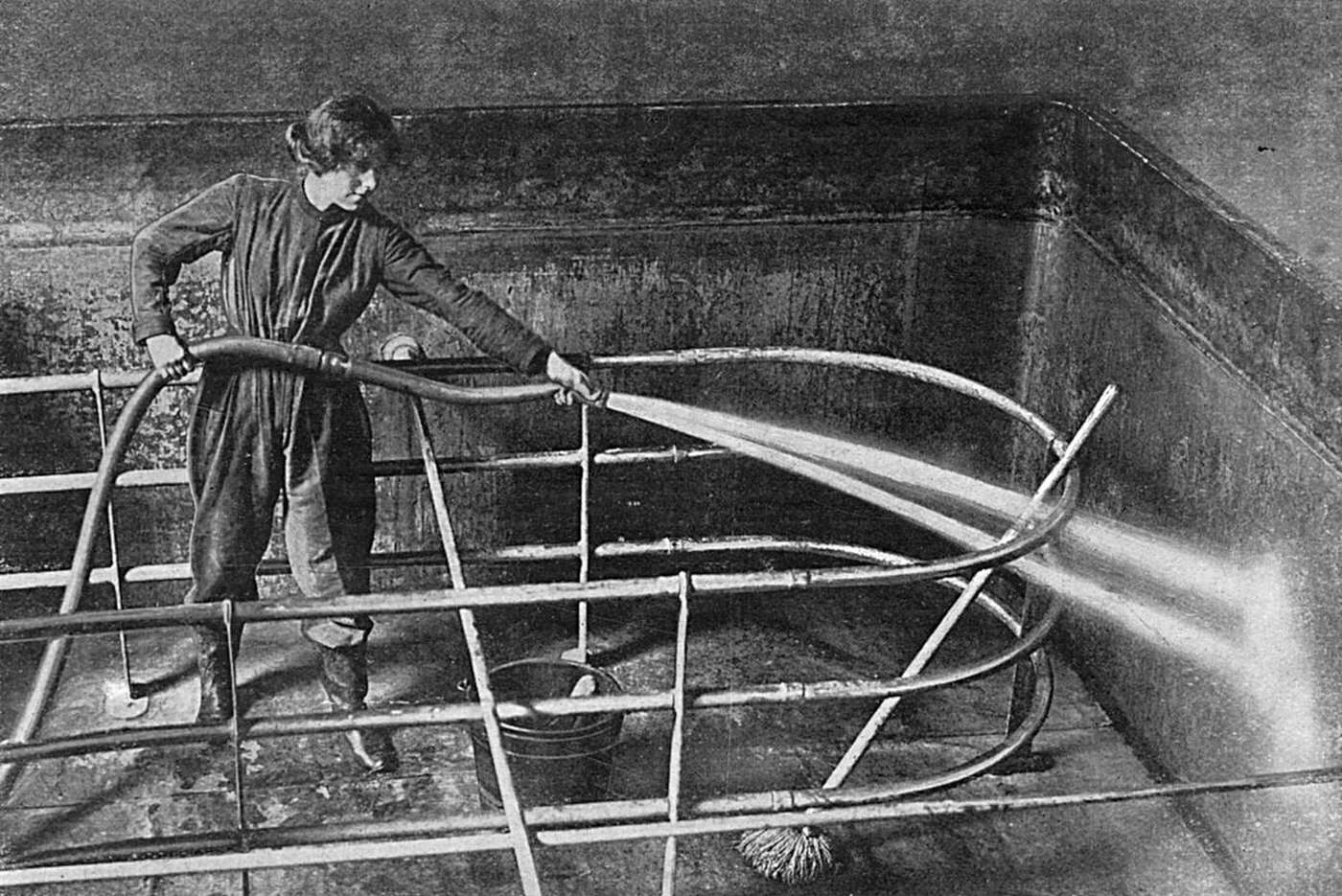

With so many male agricultural laborers away fighting, food production became a critical concern. To address this, the British government formed the Women’s Land Army (WLA) in 1917. More than 23,000 women, known as “Land Girls,” volunteered to work on farms across the country.

Their duties were varied and physically strenuous. They ploughed fields with horse-drawn plows, planted and harvested crops, milked cows by hand, and cut timber in forests as part of the Timber Corps, where they were nicknamed “Lumber Jills.” The Land Girls wore a distinctive uniform that included breeches instead of skirts, a practical and revolutionary garment for women at the time. They also took on the task of pest control; in one instance, two Land Girls were recognized for catching 12,000 rats in a single year.

In Uniform and On the Streets

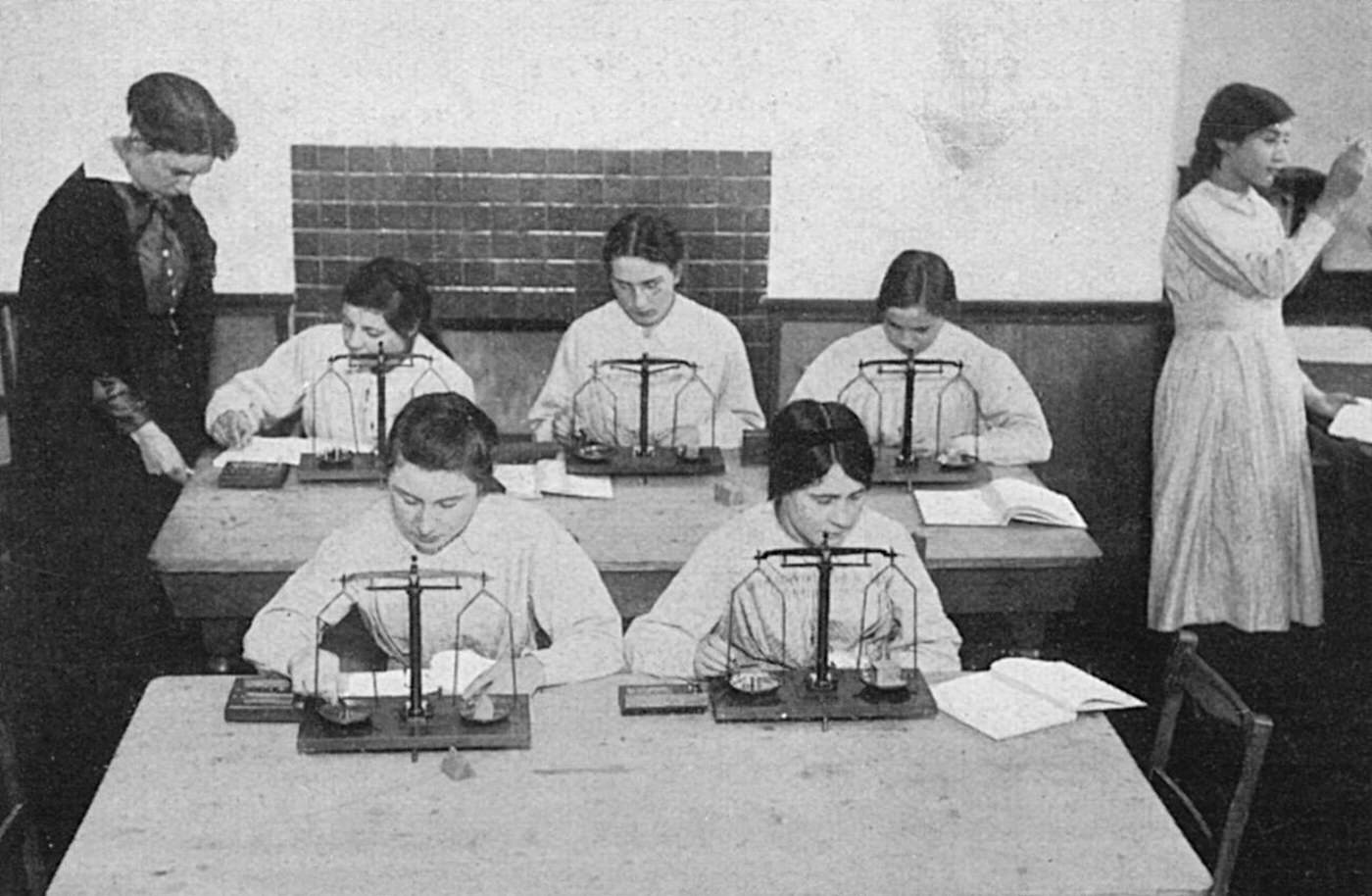

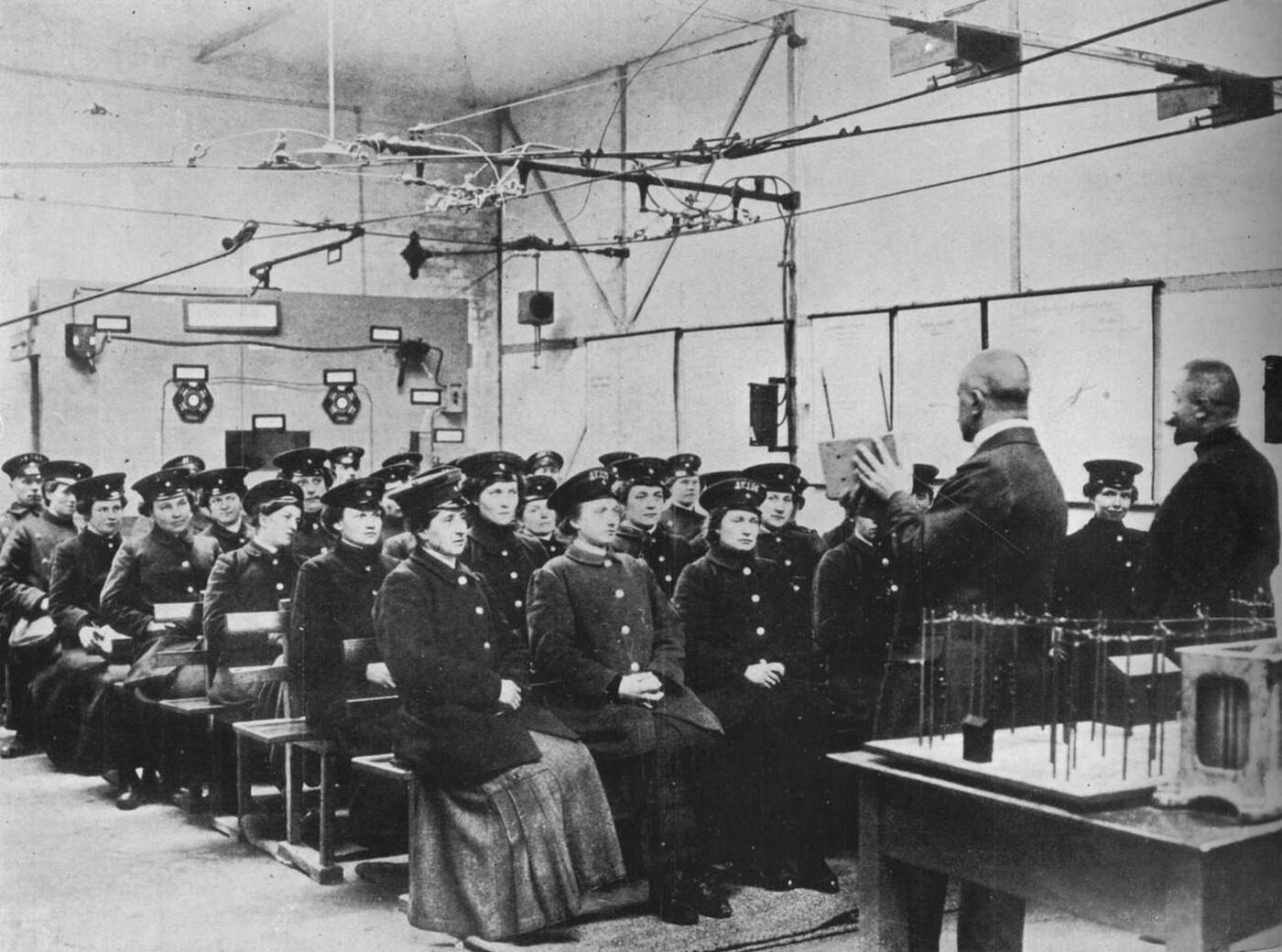

Women also took on official roles within the military in non-combat capacities. In 1917, Britain established the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). Its members served as clerks, drivers, telephone operators, and bakers in France, freeing up male soldiers for front-line duty. They did not hold military rank but were assigned grades such as “Worker” or “Forewoman.”

In the United States, a loophole in the Naval Act of 1916 that did not specify gender allowed the U.S. Navy to enlist women. Around 12,000 women joined as Yeoman (F), popularly known as “Yeomanettes.” Most performed clerical duties, but some worked as draftsmen, translators, and even torpedo assemblers. They received the same pay as their male counterparts: $28.75 per month. The U.S. Army also recruited bilingual women to serve as telephone operators for the Signal Corps in France. These “Hello Girls” worked very close to the front lines, connecting vital communications for the Allied forces.

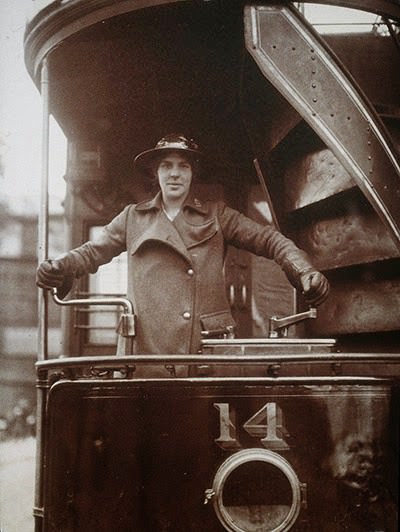

The presence of women in new roles was also highly visible in cities. They became bus and tram conductors, nicknamed “Clippies,” and served as police officers for the first time, often patrolling the areas around factories to maintain order. These new jobs demonstrated the capability of women to perform tasks essential to the functioning of a nation at war.