Refugee camps in Småland, Sweden, appeared as clusters of red wooden buildings hidden deep within thick pine forests. The Swedish government converted summer resorts, old schools, and empty barracks into temporary housing for thousands fleeing the war. Snow covered the grounds for much of the year, isolating the camps from the nearby villages. The air smelled constantly of burning birch wood, which was the primary source of heat during the coal shortages.

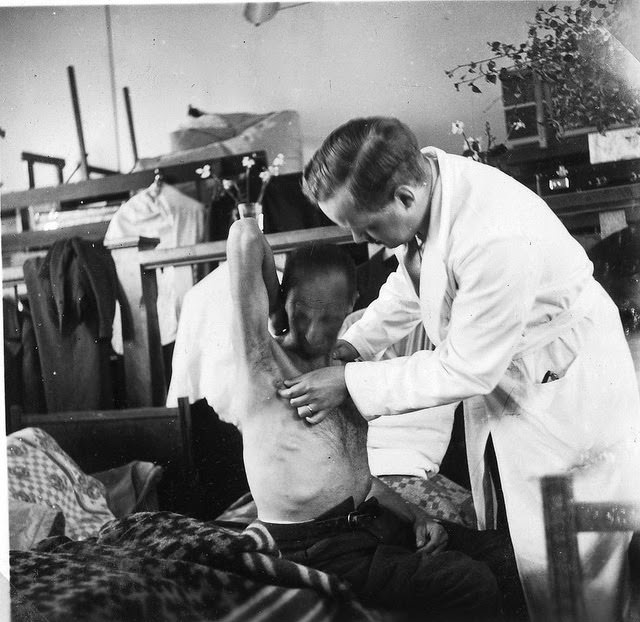

Upon arrival, every refugee underwent a strict medical examination. Nurses and doctors checked for contagious diseases like tuberculosis and typhus, which were common in war-torn Europe. New arrivals had their heads shaved and their clothes boiled to kill lice. After this process, they received a set of clean, simple clothes and were assigned a bunk in a dormitory. Privacy did not exist in these rooms, where dozens of strangers slept in rows on straw-filled mattresses.

Food was scarce and strictly rationed. The camp kitchen served meals based on what was available locally, usually consisting of oatmeal porridge, potatoes, and herring. Coffee was a luxury substitute made from roasted grain or chicory root. Refugees received ration coupons for essential goods, but the shops were often empty. To supplement their diet, families picked wild lingonberries and mushrooms in the surrounding woods during the autumn months.

Read more

Daily life revolved around work and maintenance. Since Sweden needed fuel, able-bodied men from the camps worked in the forests chopping timber. They used large two-man saws to fell trees, hauling the logs through the snow to be used for heating or construction. Women often gathered in common rooms to mend clothes, knit socks, or peel immense piles of potatoes for the communal dinners. Children attended makeshift schools organized within the camp, where they learned Swedish and continued their basic education using donated books.

Information from the outside world was the most valuable commodity in the camp. In the evenings, groups gathered around a single radio to listen to news broadcasts from the BBC or Swedish public radio. Translators shouted out updates in Polish, Danish, or Norwegian so everyone could understand the progress of the battles. Walls in the common areas became bulletin boards covered in handwritten notes. People pinned up names of missing relatives, hoping that someone in the camp or a visitor might recognize a loved one lost in the chaos of the war.