In 1959, the Soviet Union opened its doors to something it had long resisted—Western fashion shows. That year, the state officially allowed such events and ended its persecution of citizens wearing modern, trend-driven clothes. This shift created the opportunity for Madame Suzanne Lulling, head of the Dior Salon, to bring an entire Dior collection to Moscow.

The venue was the House of Culture “Wings of the Soviets,” its interior dressed in the blue, white, and red of the French flag. It was an unmistakable statement: French couture had arrived on Soviet soil. Eleven thousand invitations were issued, but they reached only the highest members of the Communist Party and select figures from the Soviet elite. Ordinary citizens were not admitted to the show itself.

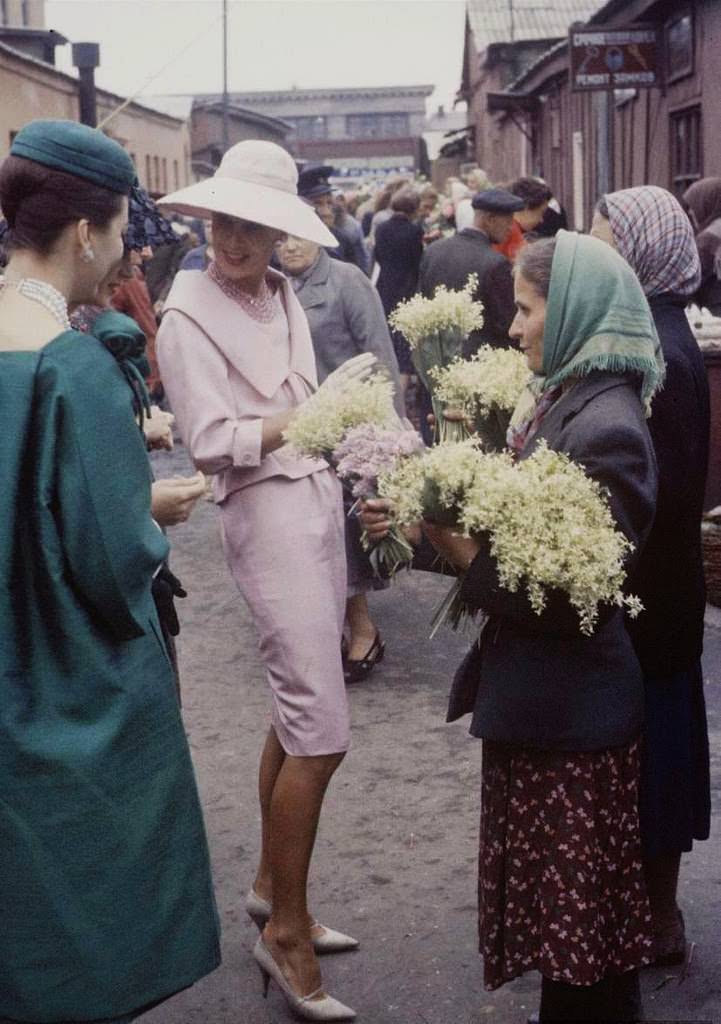

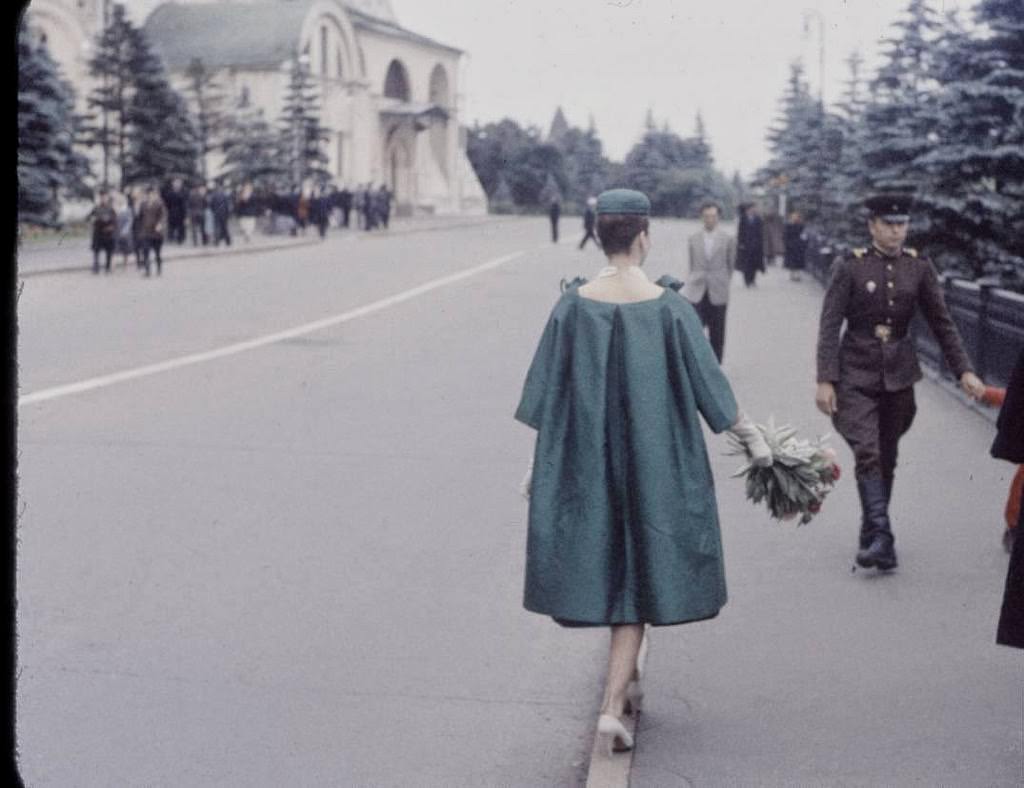

To give the public a glimpse, the organizers arranged a very different kind of presentation—a walk through the streets of Moscow. Three of the twelve models took part, wearing Dior designs that contrasted sharply with the city’s winter coats and modest silhouettes. They strolled through Red Square, visited bustling markets, and passed along key shopping streets, including the Soviet fashion district. Every step drew curious stares, as spike heels clicked against cobblestones and narrow skirts shifted against the wind.

Read more

The official photographer, Howard Sochurek, followed closely, capturing the juxtaposition of Paris couture against the Soviet backdrop. In his frames, towering models in fitted coats and elegant hats moved past onion-domed cathedrals, outdoor vendors, and clusters of passersby who stopped to watch.

Not all reactions were favorable. Pravda dismissed some of the designs as too revealing or too short, claiming such clothes would not flatter women of short stature or heavier build. A Soviet magazine took aim at the narrow skirts and stiletto heels, writing that these “bourgeois” styles forced a woman to walk awkwardly and cling to a man for support.

For Soviet authorities, European high fashion carried more than aesthetic weight. Fashion historian Djurdja Bartlett notes that constantly changing styles embodied change itself—a concept at odds with a system built on stability. In a society that valued uniformity, the idea of fashion as seasonal and unpredictable represented an unwelcome challenge.