In 1933, the same year Adolf Hitler came to power, Coca-Cola’s German branch began expanding rapidly. The company’s local head, Max Keith, understood how to navigate the Nazi-controlled business world. He kept the product free of political statements but aligned the brand with national events and values that passed censorship.

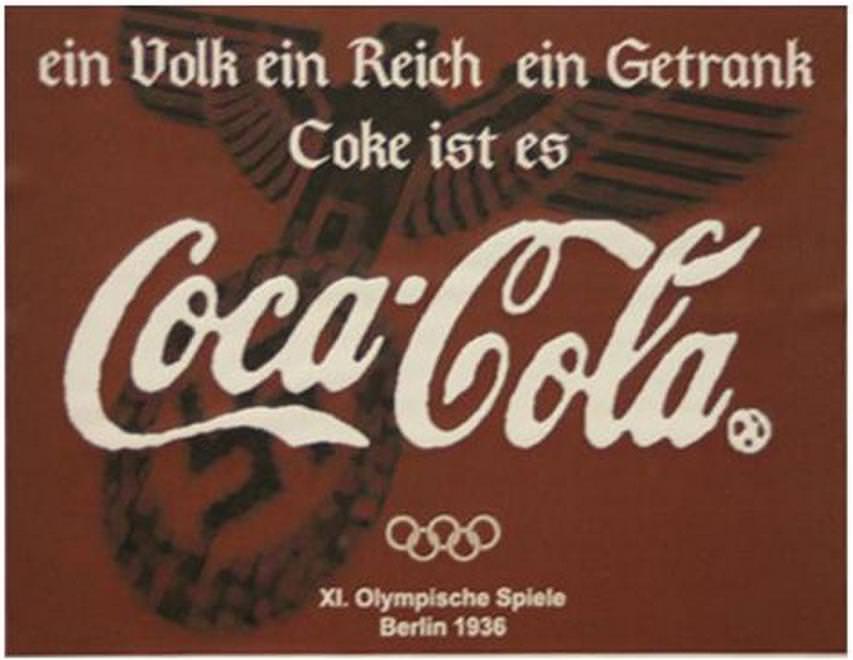

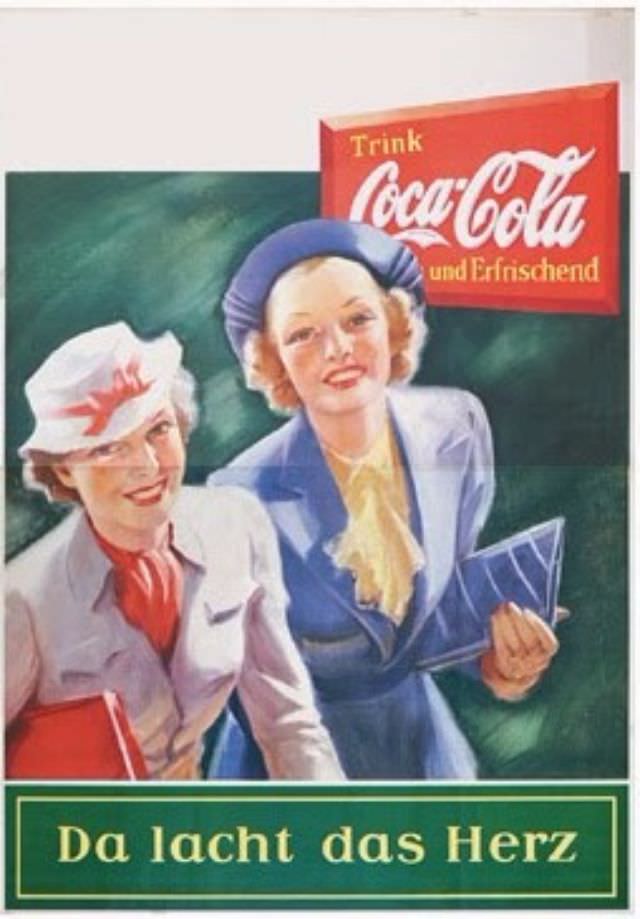

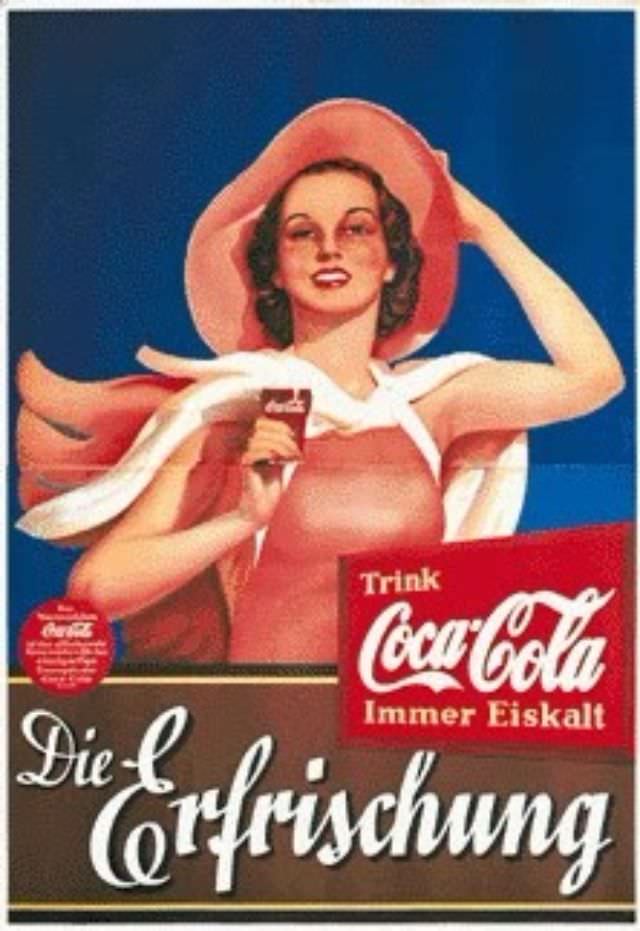

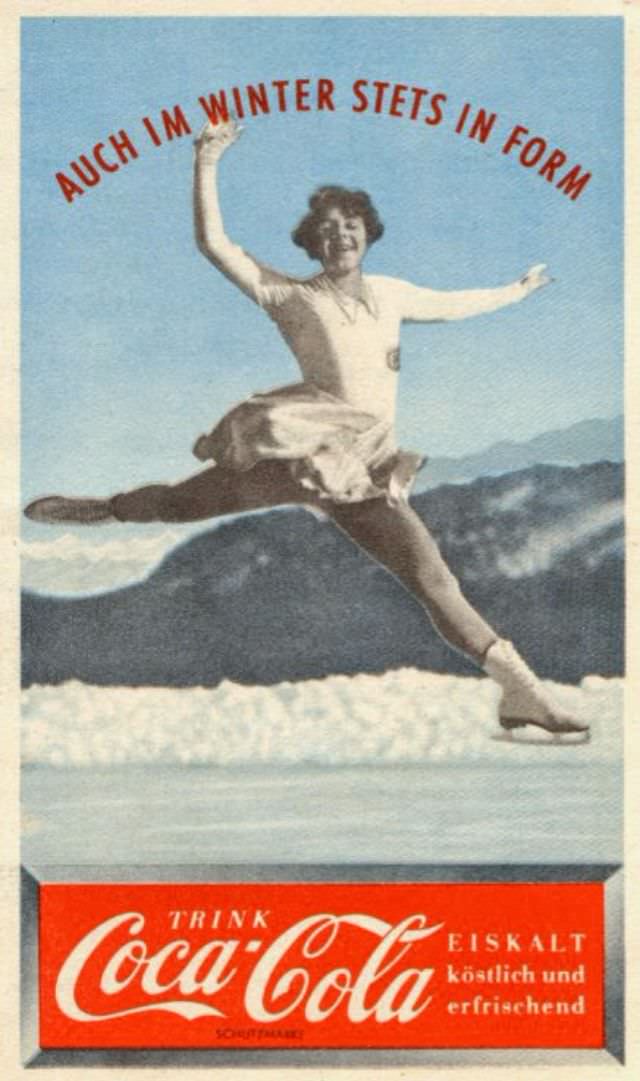

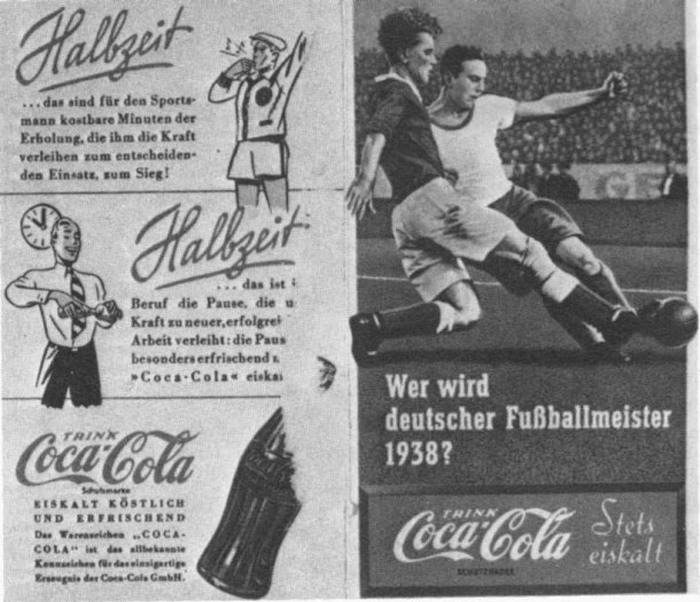

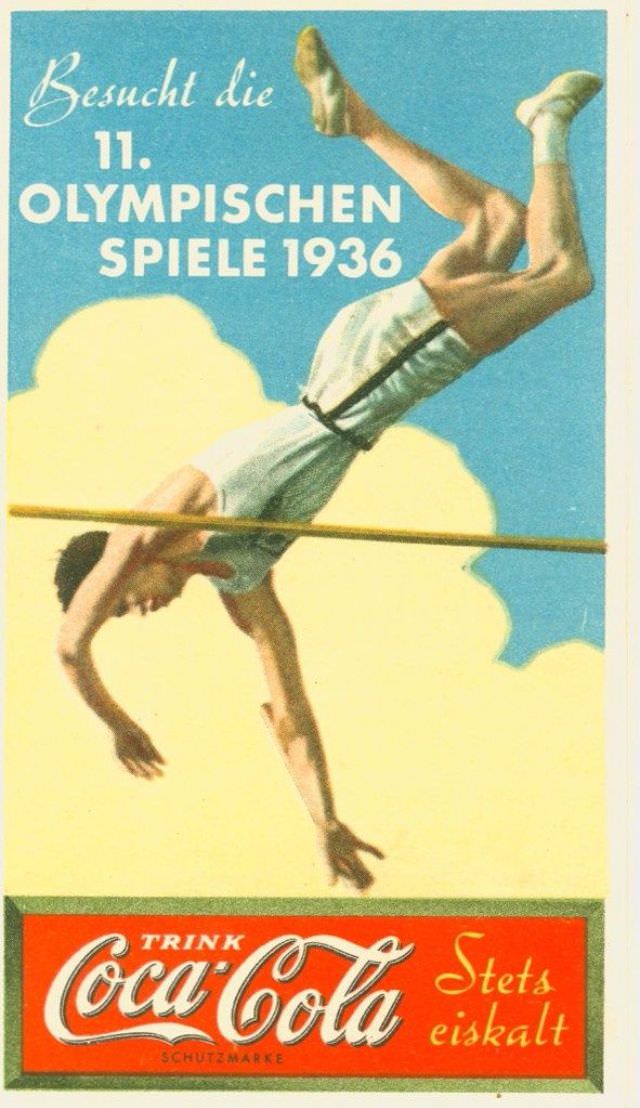

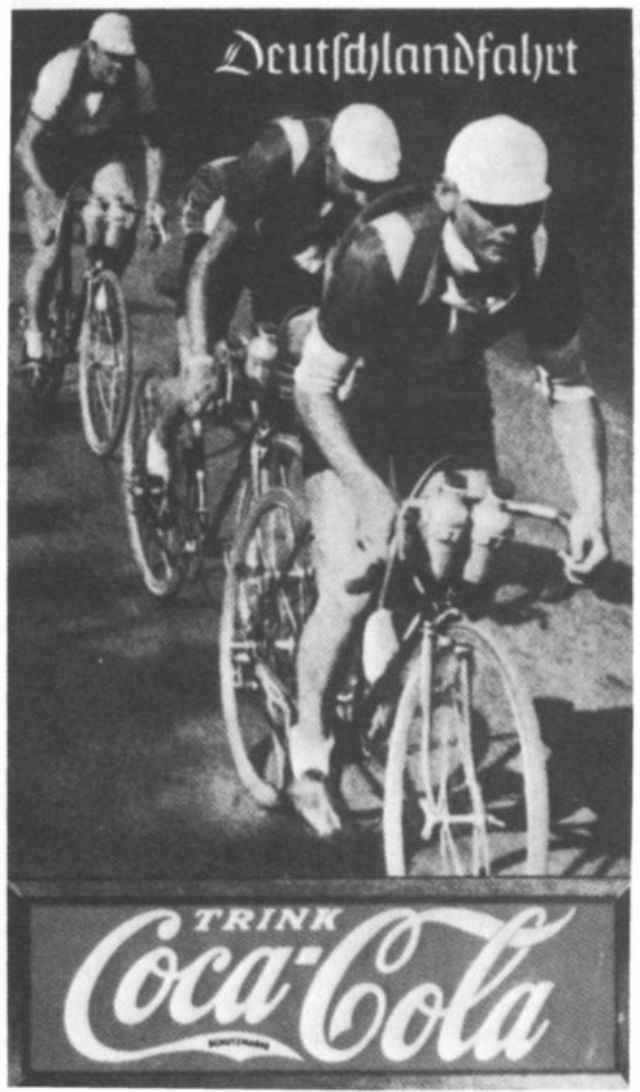

By the mid-1930s, Coca-Cola was sponsoring events across Germany, including the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Ads from the period showed cheerful Germans enjoying the drink in settings that matched official propaganda imagery—healthy, happy, and loyal to the Reich. The company’s red-and-white branding blended easily into a country already covered in red banners and white symbols.

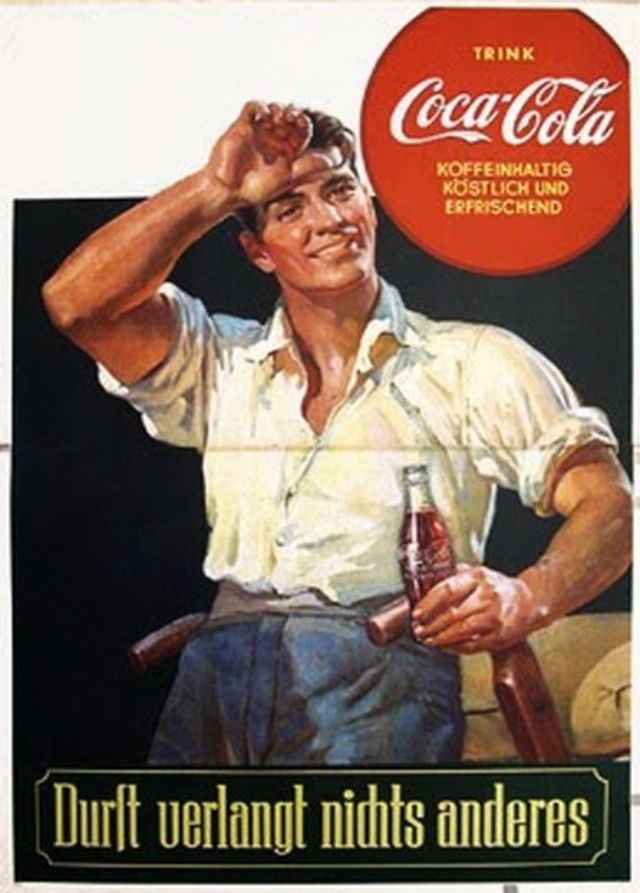

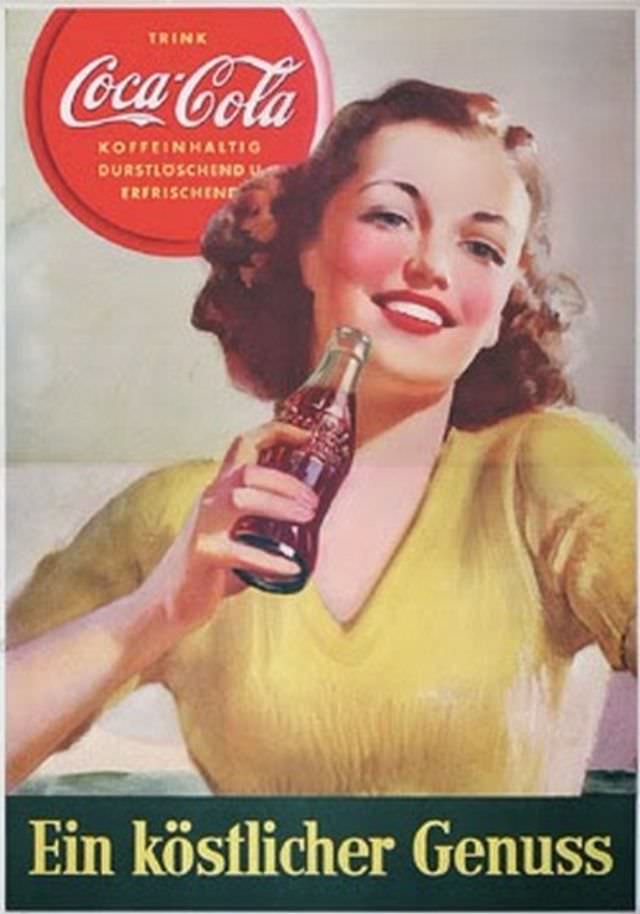

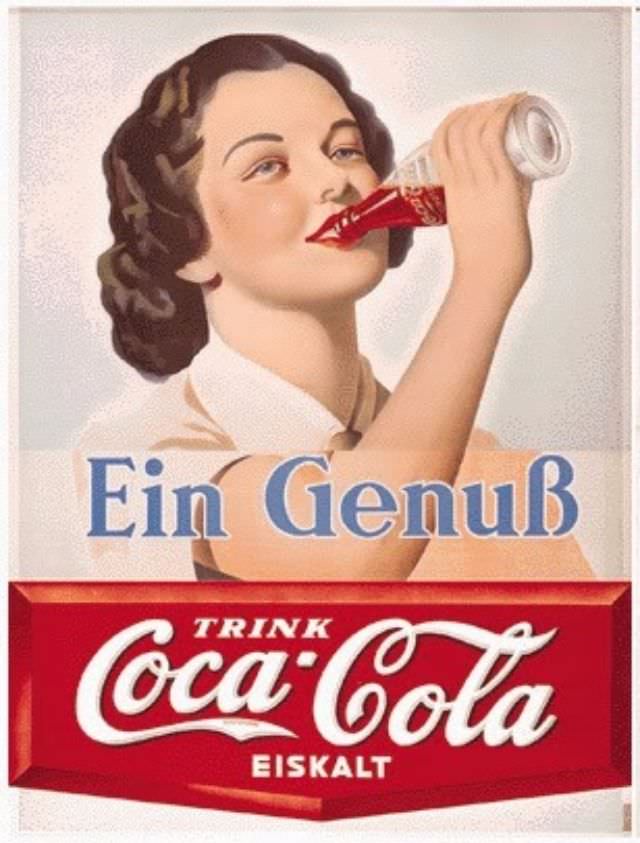

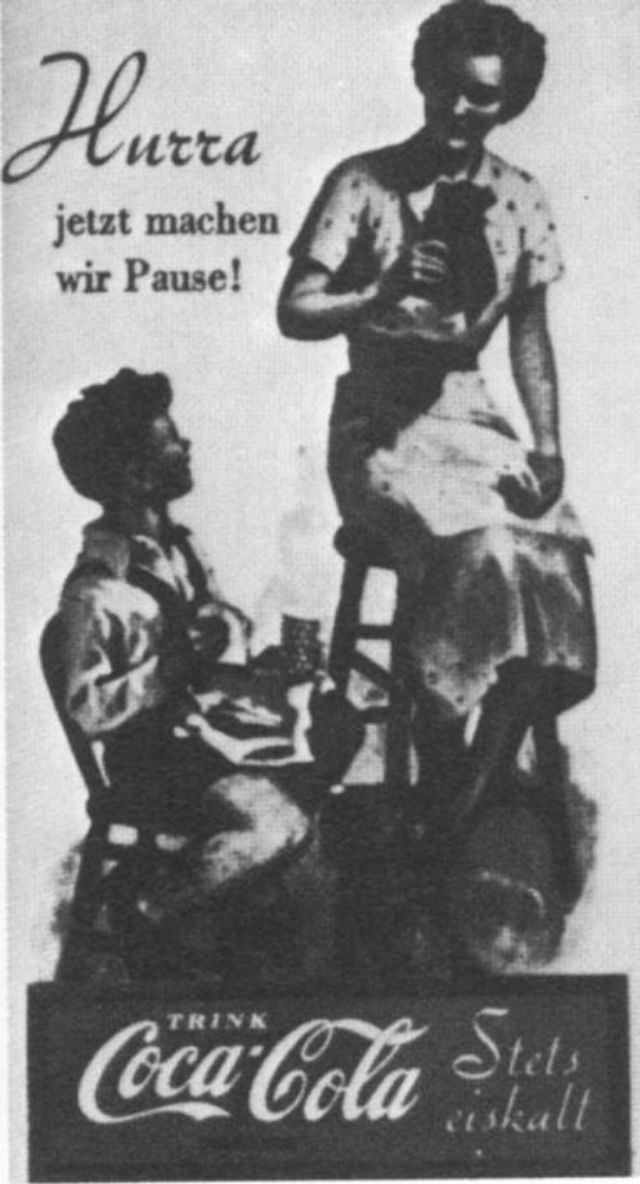

Coca-Cola’s marketing in Nazi Germany often focused on sports, youth culture, and modernity. Posters showed athletes mid-action, holding the iconic glass bottle. Slogans emphasized refreshment, energy, and togetherness, echoing themes the regime wanted to promote. There was no political messaging in the ads themselves, but their tone fit seamlessly into the climate of the time.

Read more

Max Keith’s branch sold millions of bottles annually. Production facilities operated in multiple German cities, ensuring the drink was available to both civilians and military personnel. The product became so common that it showed up in soldiers’ canteens, factories, and company picnics. Even during wartime shortages, Coca-Cola found ways to keep production going, substituting ingredients when imports were blocked.

A striking wartime anecdote came from the North African front. German troops discovered a cache of Coca-Cola left by retreating Allied forces. Without ice, the drink was considered undrinkable under the scorching desert sun. Luftwaffe pilots solved the problem by wrapping bottles in wet cloth, tying them to the wings of their Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, and cooling them in midair. On return, they drank the now ice-cold bottles on the runway—an image that could have been straight out of a bold Coca-Cola campaign.

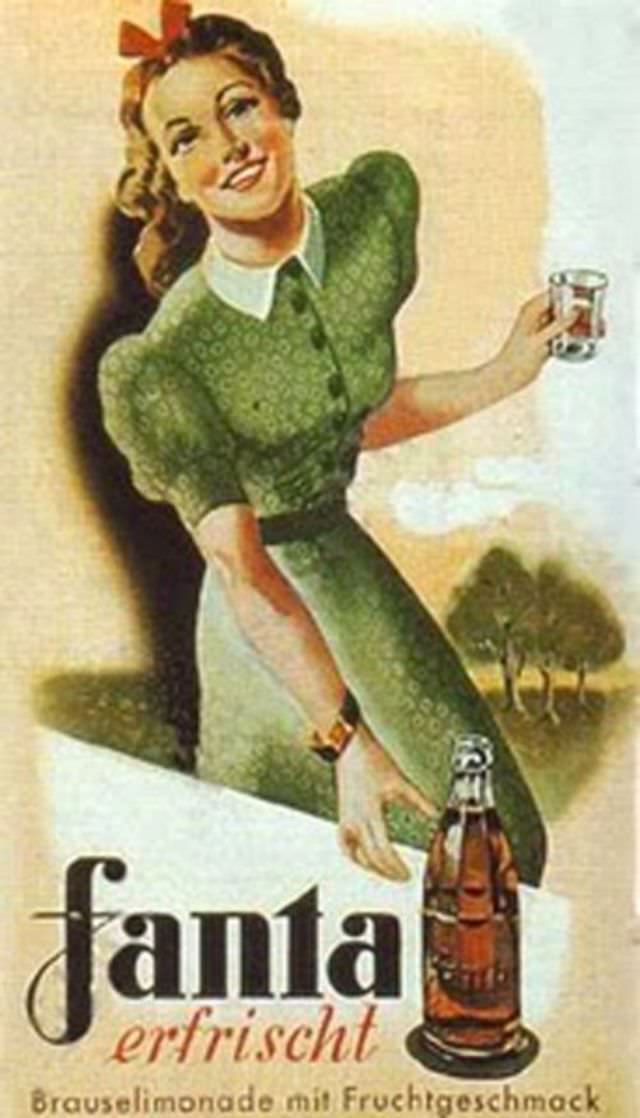

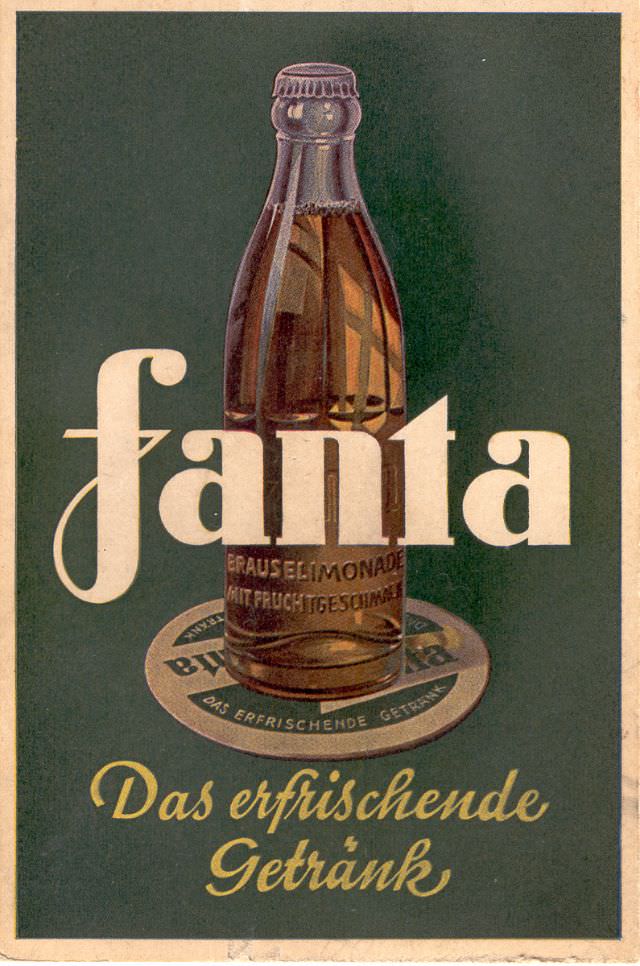

As the war dragged on and Allied imports stopped, Keith’s team created a substitute drink: Fanta. It used ingredients available inside the Reich, like whey and apple fiber, allowing the company to maintain operations despite shortages. Fanta was marketed heavily in wartime Germany, often alongside older Coca-Cola imagery in stores and factories.

By 1945, Coca-Cola had been deeply embedded in German life for over a decade. Its advertisements from the Nazi period reveal a careful balancing act—selling a modern, American product in a tightly controlled dictatorship while avoiding overt political entanglement in its marketing.