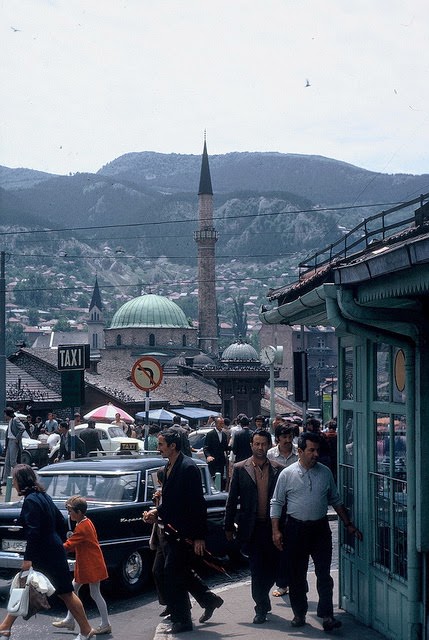

Yugoslavia in the 1970s occupied a unique space between the capitalist West and the communist East. The country operated under a specific form of socialism that allowed for a consumer lifestyle unknown in the Soviet bloc. The red Yugoslav passport stood as the most powerful symbol of this freedom. Unlike citizens of Hungary or Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavs crossed borders without needing special exit visas. They traveled to West Germany for temporary work or vacationed in Greece and Turkey, moving freely between rival political worlds.

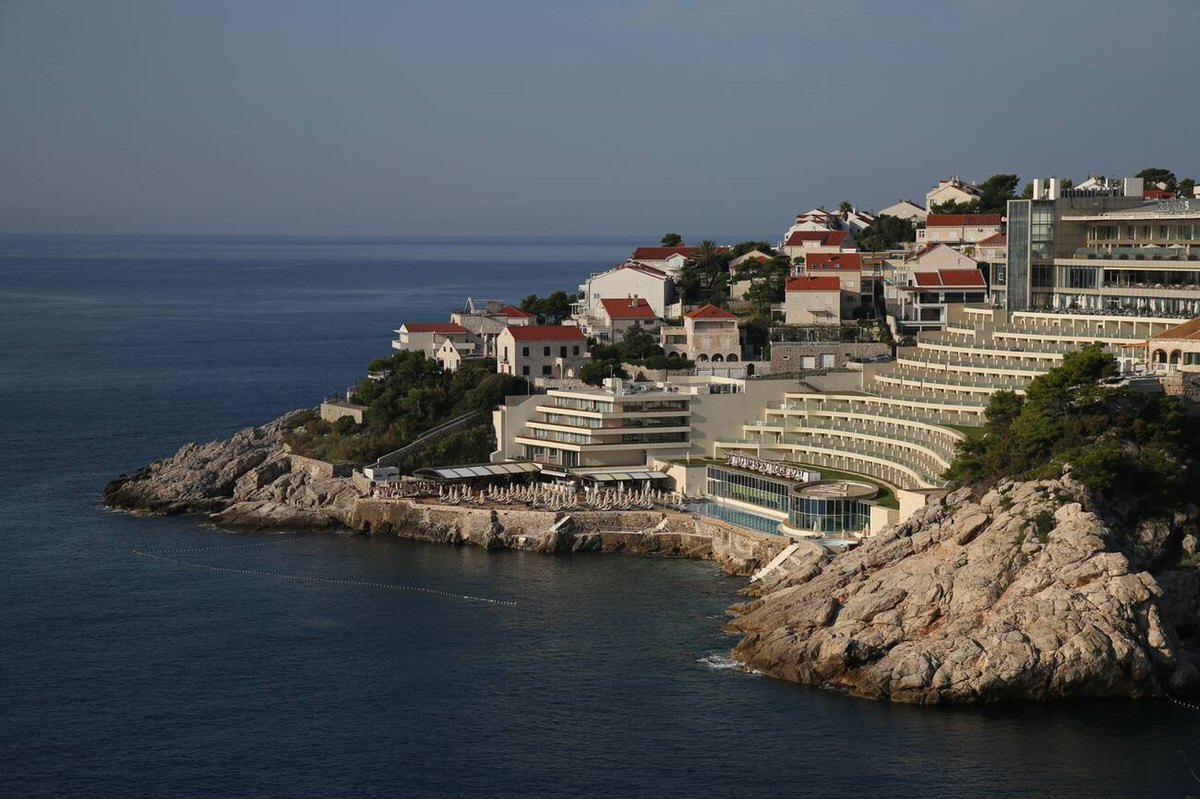

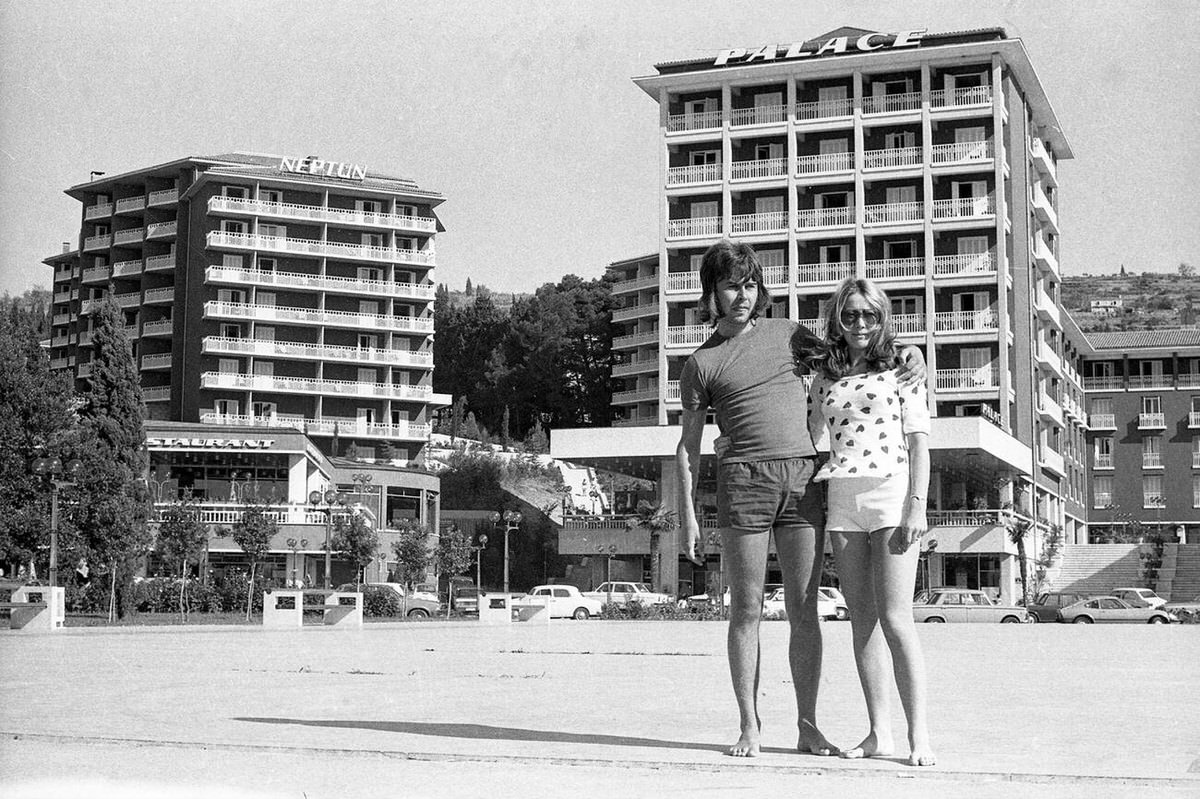

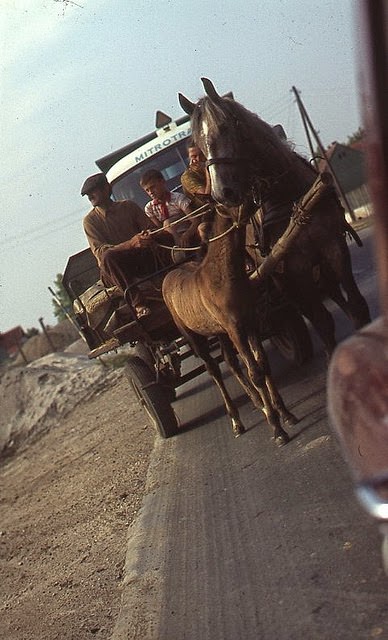

The economy ran on a system of easy credit. Banks issued checkbooks that citizens used to buy everything from furniture to groceries, often paying in installments that stretched over months. Inflation existed, but wages rose fast enough to keep up with prices. This financial freedom fueled a construction boom. Middle-class families built vikendice, or weekend houses, in the countryside and along the coast. These small second homes became a standard part of life for factory workers and professionals alike.

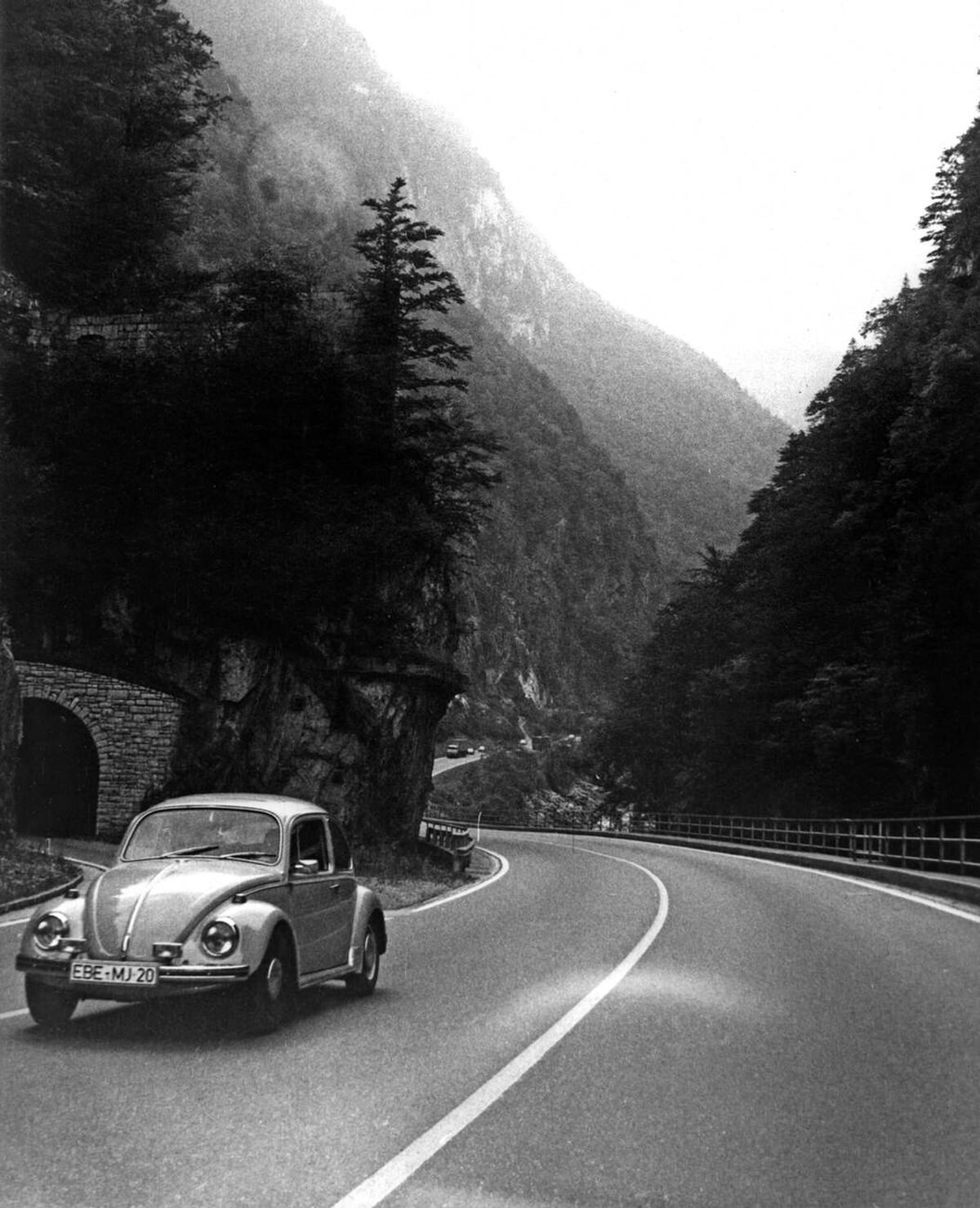

Shopping trips to Trieste, Italy, were a national ritual. On weekends, thousands of cars formed long lines at the border crossing. The destination was the Ponterosso market, where Yugoslavs purchased blue jeans, coffee, and detergent. These western goods were status symbols. Back home, grocery stores stocked a mix of domestic and foreign products. The local soda, Cockta, competed directly with Coca-Cola, which was produced locally under license.

Read more

The Zastava 750, affectionately called the “Fića,” ruled the roads. This small car was a licensed version of the Fiat 600 and served as the first vehicle for many families. Despite its tiny engine and cramped interior, owners packed it with camping gear, food, and luggage for the annual drive to the Adriatic Sea. Later in the decade, the Zastava 101, or “Stojadin,” arrived. It offered a modern hatchback design that signaled the growing purchasing power of the population.

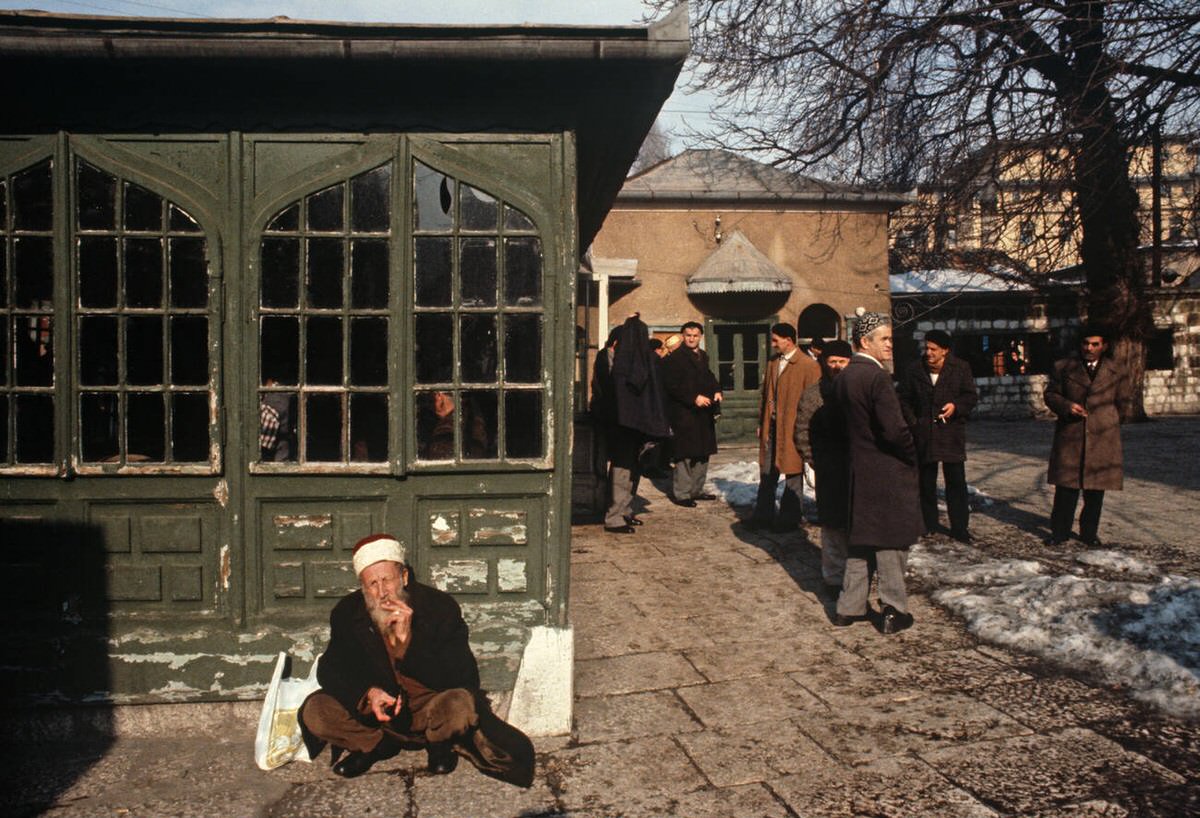

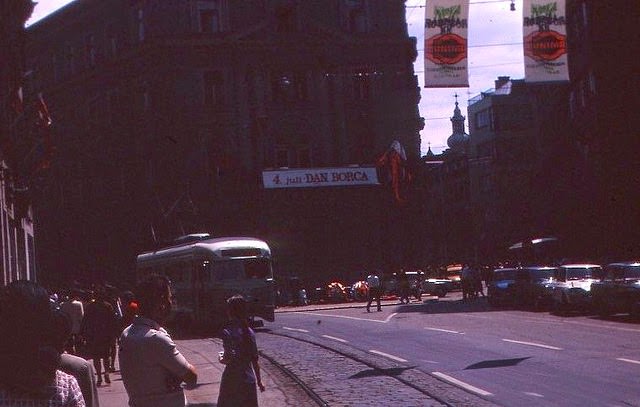

Music played a massive role in youth culture. The government did not ban Western rock and roll; instead, they encouraged a domestic version. Bands like Bijelo Dugme filled football stadiums, playing a genre known as “Shepherd Rock” that mixed hard rock with local folk melodies. Record stores in Belgrade, Zagreb, and Sarajevo sold vinyl LPs of the Rolling Stones and Deep Purple alongside local acts.

Marshal Tito remained the undisputed center of political life. His photograph hung in every school classroom and government office. In 1974, the government ratified a new constitution that decentralized power, giving more authority to the individual republics. Large public holidays, such as Youth Day, featured massive synchronized stadium performances where thousands of participants danced and formed shapes to honor the leader. Despite the underlying political complexities, the average citizen focused on the tangible improvements in their daily standard of living.