In the first half of the 20th century, Shanghai was a city of dramatic contrasts, a place where East and West collided in a vibrant and often chaotic mix. Known as the “Paris of the East,” it was a global hub of finance, culture, and vice, divided into distinct districts that created vastly different worlds for its inhabitants.

The Divided City: Concessions and the Old Town

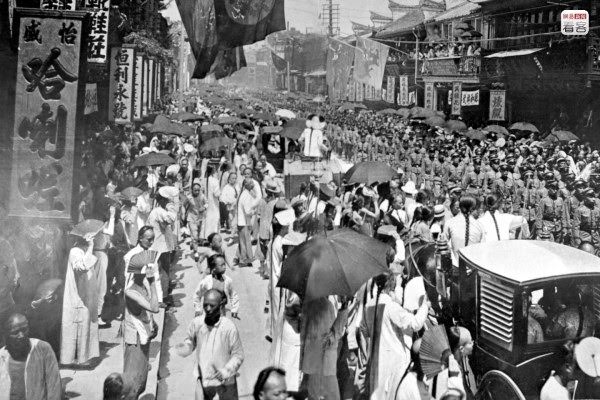

Shanghai’s unique character stemmed from its political structure. The city was carved into three main parts: the International Settlement, governed by a council of British and American businessmen; the French Concession, administered by the French consul; and the original Chinese walled city. This division created a unique environment where different laws, languages, and cultures operated side by side.

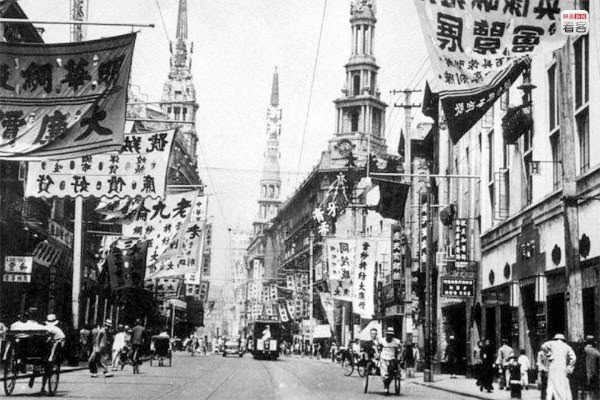

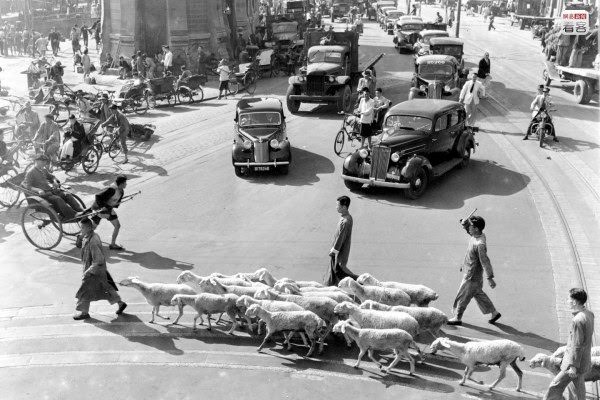

The heart of foreign power and wealth was the Bund, a waterfront promenade along the Huangpu River. This area was lined with grand, European-style banks, trading houses, and hotels built by the British, French, and Americans. Here, foreign businessmen and wealthy Chinese traders conducted business that connected China to the global economy. The streets were filled with a mix of modern automobiles, electric trams, and the traditional, man-powered rickshaws.

Read more

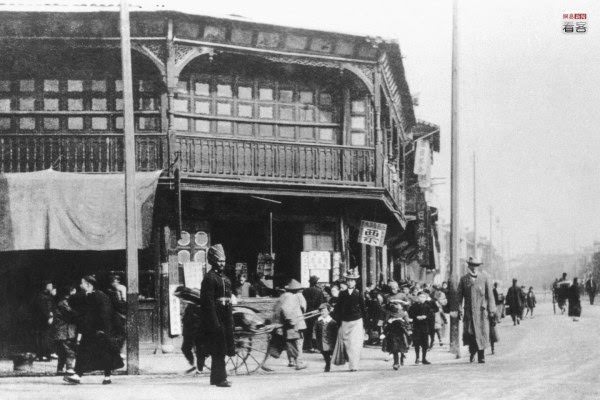

Just beyond this modern facade, the majority of Shanghai’s Chinese residents lived in dense neighborhoods filled with shikumen housing. These were two- or three-story stone houses that blended Chinese and Western architectural styles, organized along narrow alleyways known as longtangs. These alleyways served as communal living spaces where families cooked, children played, and neighbors socialized, creating a tight-knit but crowded community life.

A Hub of Commerce and Culture

Daily life in Shanghai was driven by commerce. Nanjing Road was the city’s premier shopping street, home to massive, modern department stores like Wing On and Sincere. These stores were marvels of their time, featuring everything from imported luxury goods to traditional silks, and even had rooftop amusement parks to attract customers.

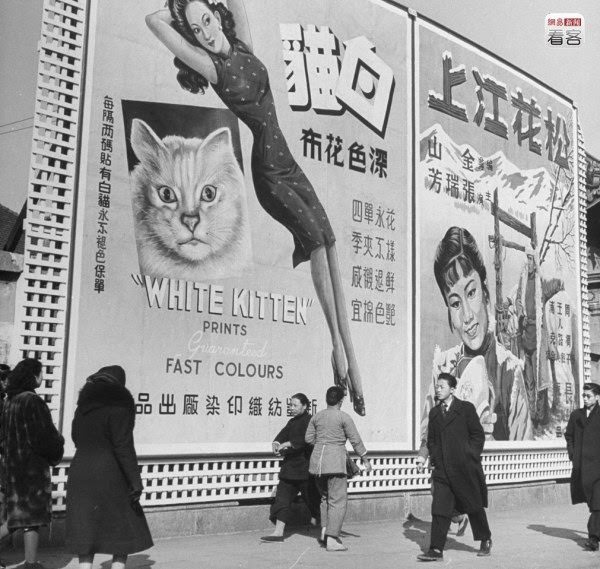

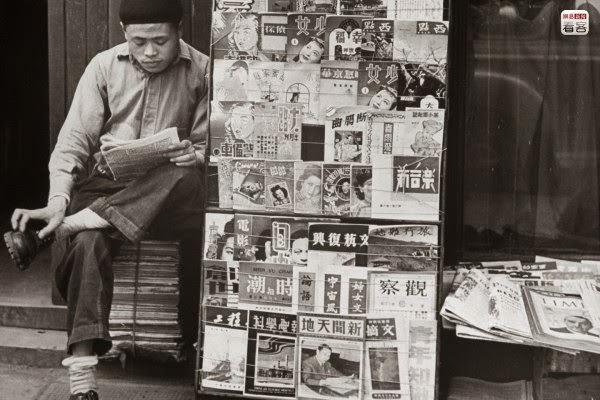

The city was also the center of China’s burgeoning entertainment industry. It was the birthplace of Chinese cinema, with a thriving film industry that produced hundreds of movies. By the 1920s and 1930s, Shanghai had also developed a legendary nightlife. Its numerous ballrooms, nightclubs, and cabarets were alive with the sound of jazz music, a new and exciting sound brought to the city by American and Filipino musicians. Wealthy patrons danced the night away in glamorous venues, while the city also harbored a darker side with its numerous opium dens and gambling houses.

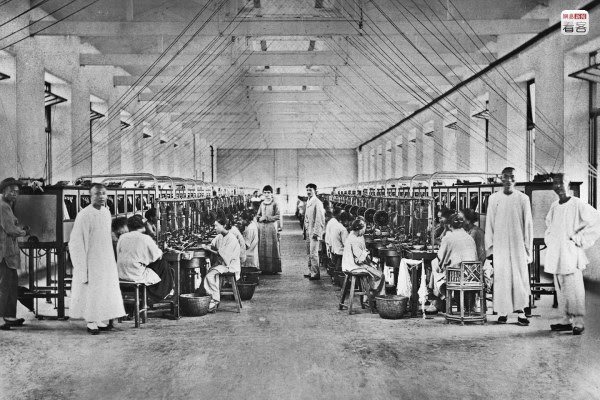

The Reality for the Working Class

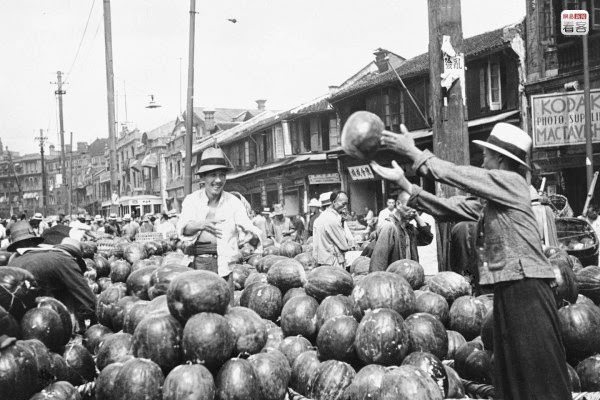

For the vast majority of Shanghai’s population, life was far from glamorous. The city’s economic boom attracted millions of migrants from the countryside who were seeking work. Many found jobs as factory workers in the city’s textile mills and industrial plants, or as laborers on the docks. The most visible members of the working class were the rickshaw pullers, who transported people and goods through the crowded streets for meager pay.

These workers lived in extreme poverty, often in makeshift straw huts or overcrowded tenement buildings on the outskirts of the foreign concessions. Their daily existence was a constant struggle for survival, a stark contrast to the opulence on display along the Bund and Nanjing Road. This deep divide between the rich and the poor was a defining feature of Shanghai society. This volatile and vibrant era came to an end with the Japanese occupation beginning in 1937 and the subsequent Communist victory in 1949, which completely transformed the city.

![At the beginning of the 20th century, movies were one of the most important entertainments for people in Shanghai. In the 1920s, Shanghai had 40,000 theater seats, extremely high attendance, and the most popular movies were wuxia [martial arts] and family dramas. Photo is of the office of the Star Film and Theater School that was founded in 1922. This company made many of the most successful films of the time as well as trained a group of the most dazzling stars of the Shanghai Bund.](https://www.bygonely.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Shanghai_Life_20th_Century_7.jpg)

![Apart from films, sports competitions and the like had also become a pursuit of high society. They never tired of tennis, horse racing and similar sports. Quite a few foreigners established jockey clubs and such organizations here [in Shanghai]. Photo is of three sisters awaiting the start of a tennis match. .](https://www.bygonely.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Shanghai_Life_20th_Century_9.jpg)