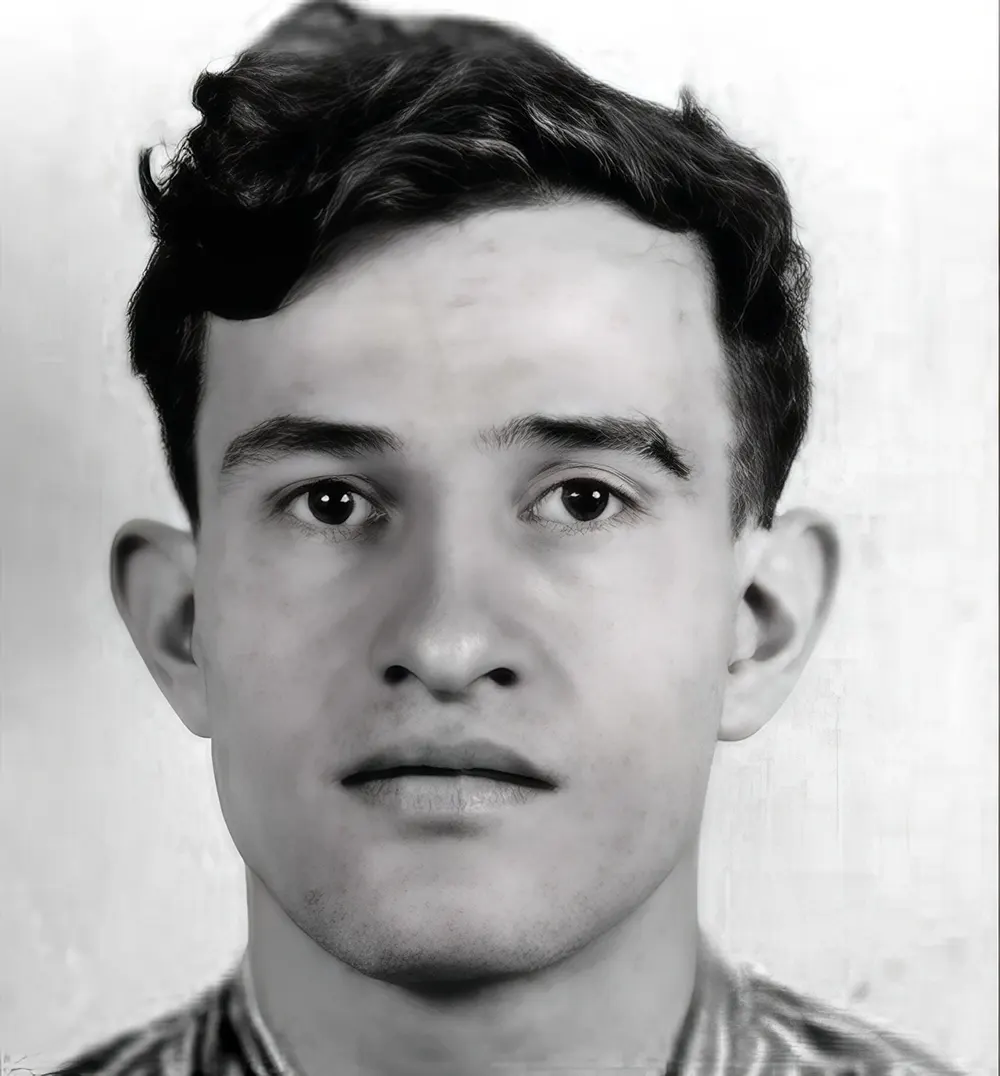

Joe Arridy was born on April 29, 1915, in Pueblo, Colorado. His parents, Henry and Mary Arridy, were immigrants from Syria. Joe was one of five children. From an early age, it was clear that Joe was different. He struggled with learning and had difficulty understanding things that other children found easy. By the time he was six, his parents realized that he had a mental disability.

Joe’s family tried to help him as much as they could, but it was tough. In the early 20th century, there was little understanding or support for people with intellectual disabilities. His parents often felt overwhelmed and unsure of how to care for him. At ten, Joe was sent to the State Home and Training School for Mental Defectives in Grand Junction, Colorado. This was a place for children who had trouble learning and needed extra help. Joe stayed there for several years. Despite his challenges, Joe was known to be friendly and gentle. He enjoyed simple things like playing with toys and listening to music.

In August 1936, when Joe was 21 years old, a horrific crime occurred in his hometown of Pueblo. Dorothy Drain, a 15-year-old girl, was brutally attacked in her home. She was hit on the head and died from her injuries. Her younger sister, Barbara, was also attacked but survived. The community was shocked and terrified. There was intense pressure on the police to find the person responsible for such a heinous act.

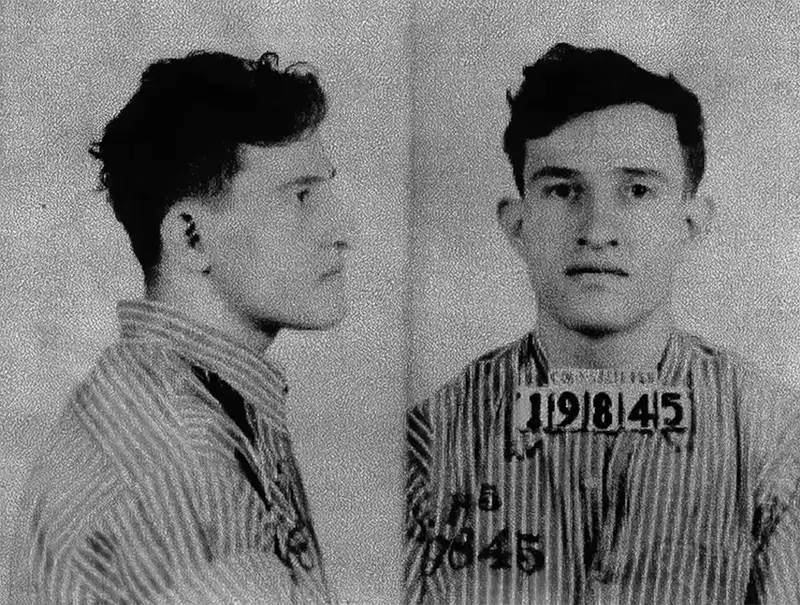

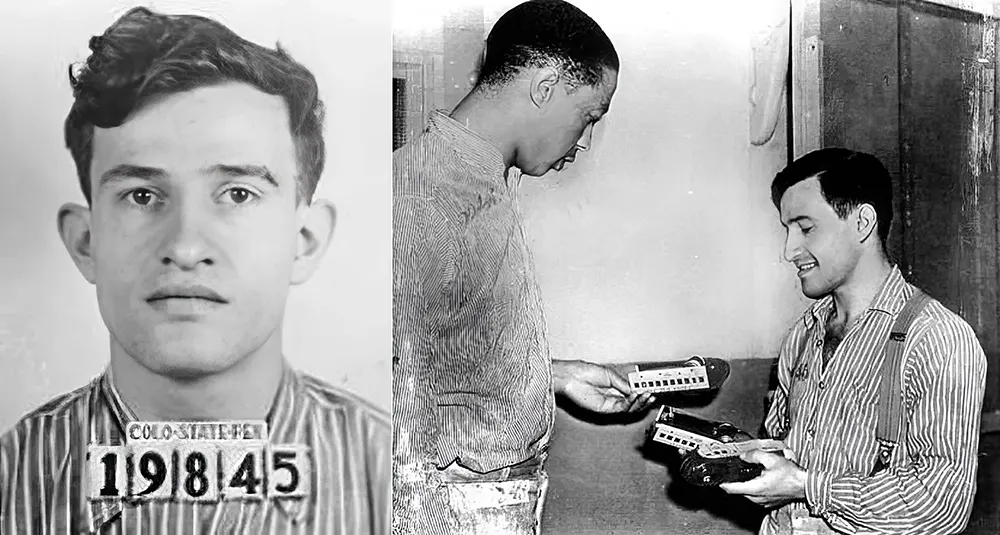

At the same time, Joe had wandered away from the state home. He had a habit of roaming and often got lost. He was eventually found in Cheyenne, Wyoming, by Sheriff George Carroll. Sheriff Carroll questioned Joe and claimed that Joe had confessed to the murders. However, it’s important to understand that Joe had a mental age of about six and likely did not comprehend the situation or the questions being asked. His so-called confession was full of inconsistencies and did not match the details of the crime.

Despite the dubious nature of the confession, Joe was brought back to Colorado to face trial. The trial began on October 12, 1936. Joe’s lawyer, Joseph J. McGee, argued passionately that Joe could not have committed the crime. McGee pointed out that Joe had the mental capacity of a young child and did not understand what was happening around him. He also highlighted the lack of physical evidence linking Joe to the crime scene.

Nonetheless, the jury found Joe guilty, and he was sentenced to death. During the trial, another man named Frank Aguilar was also arrested for the same crime. Aguilar had worked for Dorothy Drain’s father and was found with a blood-stained hammer. He confessed to the crime and was also sentenced to death. Aguilar’s confession should have cast serious doubt on Joe’s guilt, but it did not change Joe’s fate.

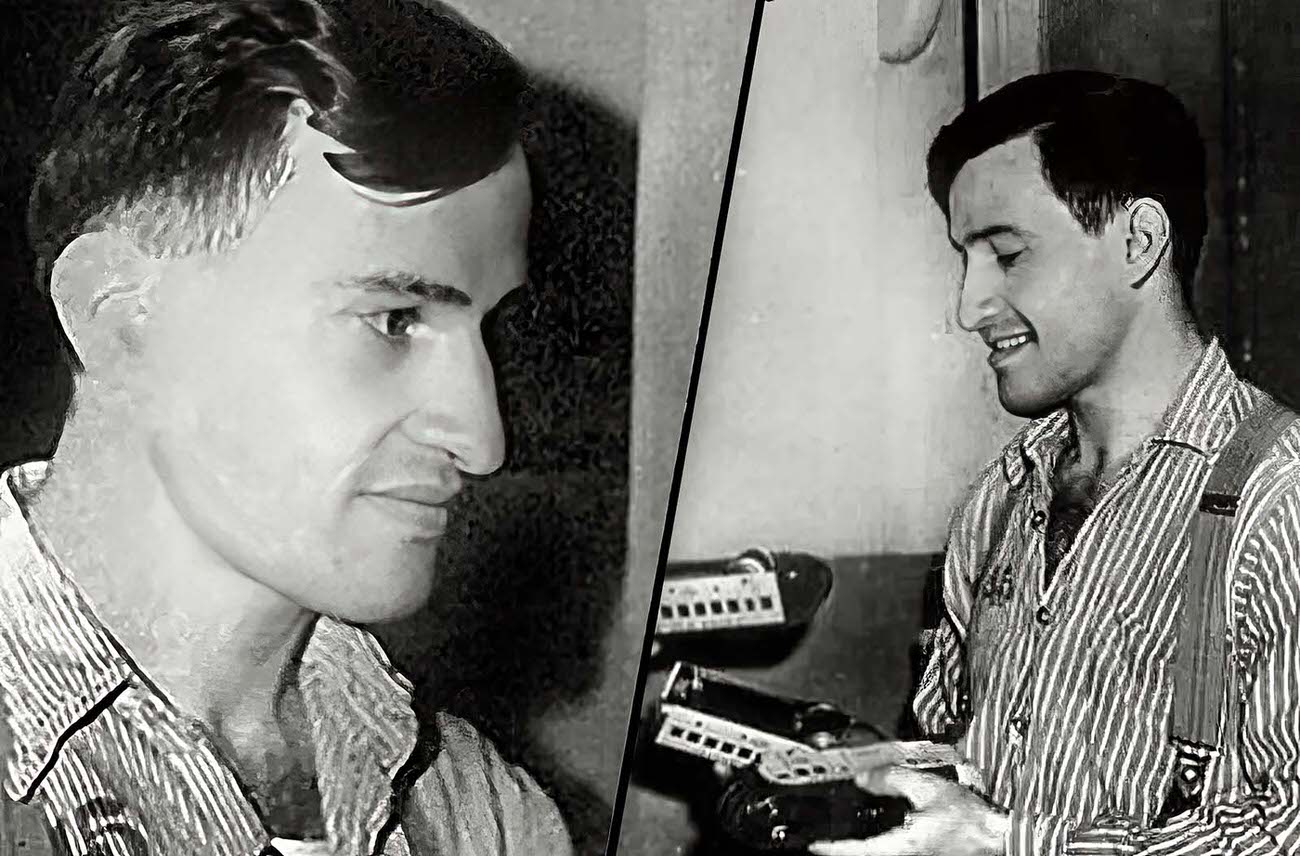

Joe’s time in prison was marked by a tragic innocence. He did not understand that he was on death row or what execution meant. The prison warden, Roy Best, developed a fondness for Joe and believed in his innocence. Warden Best described Joe as “the happiest prisoner on death row.” Joe spent his days playing with toys, drawing pictures, and enjoying simple pleasures like ice cream. He smiled often and seemed unaware of the gravity of his situation.

Many people, including Warden Best, tried to save Joe. They wrote letters to the governor and filed appeals, hoping to delay or overturn the execution. They argued that Joe’s mental disability should exempt him from the death penalty and that his confession was unreliable. Unfortunately, their efforts were unsuccessful.

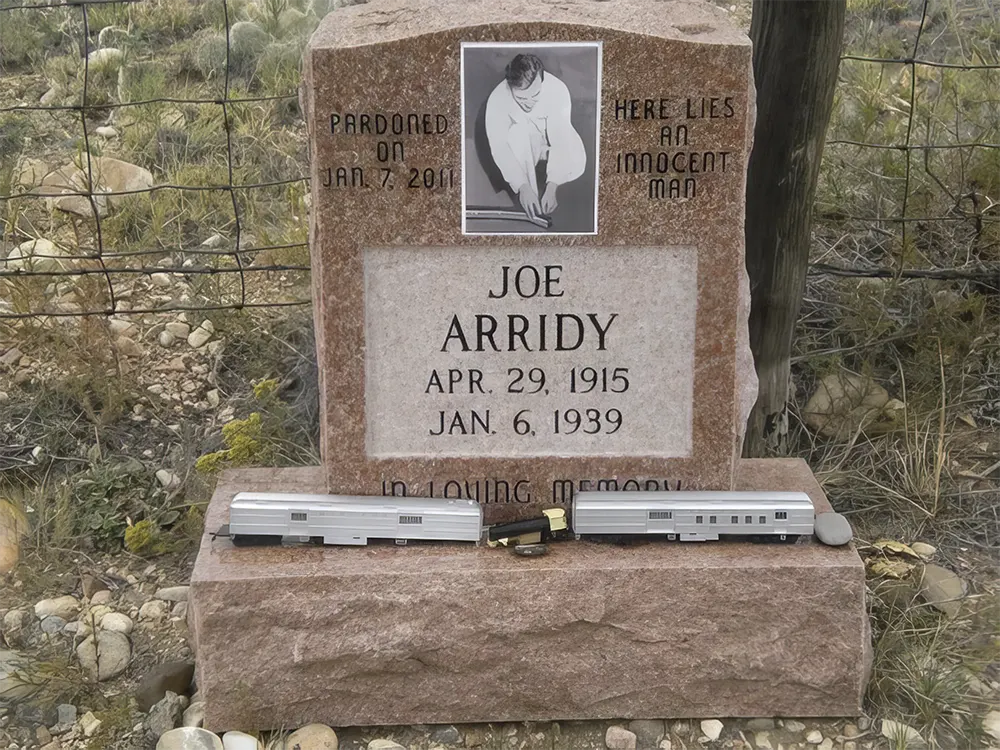

On January 6, 1939, Joe Arridy was executed in the gas chamber at the Colorado State Penitentiary. He was 23 years old. His last meal was ice cream, a treat he loved. As he was led to the gas chamber, Joe remained cheerful and calm. He did not understand what was about to happen. He went to his death smiling, still holding on to a toy train that Warden Best had given him.

After Joe’s execution, many people continued to believe in his innocence. His case was reviewed multiple times over the years, and numerous advocates worked to clear his name. They pointed out the flaws in the investigation, the unreliable confession, and the lack of solid evidence. Joe’s mental disability should have been a significant factor in the case, but it was largely ignored at the time.

In 2011, after decades of efforts by lawyers, activists, and historians, Colorado Governor Bill Ritter granted Joe Arridy a posthumous pardon. This means that the state officially recognized that Joe did not commit the crime and should not have been executed. The pardon was a symbolic act, acknowledging the grave injustice done to Joe and his family.

Joe Arridy’s story is a tragic example of how the justice system can fail. It highlights the dangers of relying on confessions from individuals who do not fully understand their circumstances. Joe’s case also underscores the need for better protection and understanding of people with intellectual disabilities within the legal system.

In the years since Joe’s execution, there have been significant changes in how the legal system handles cases involving people with mental disabilities. Today, there are laws and protections in place to ensure that individuals like Joe receive fair treatment. For example, the Supreme Court ruled in Atkins v. Virginia (2002) that executing people with intellectual disabilities is unconstitutional. This ruling has helped to prevent similar injustices from occurring.

Joe’s tragic fate has also led to increased awareness about the need for proper legal representation for people with mental disabilities. Today, there are more resources and support systems in place to ensure that individuals with intellectual disabilities have access to competent legal defense. Organizations like The Arc and the Innocence Project work tirelessly to prevent wrongful convictions and advocate for those who cannot speak for themselves.