When World War II ended, most of Europe celebrated. But in the mountains and cities of Greece, the fighting was just getting started. A brutal civil war was about to erupt, tearing the nation apart and turning it into the first hot battlefield of the new Cold War. This wasn’t a simple conflict; it was a storm that had been brewing for years, born in the chaos of Nazi occupation.

The Seeds of Hate: Resistance and Rivalry

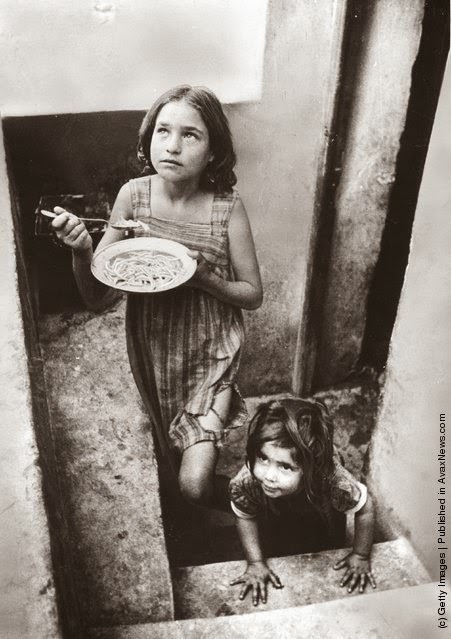

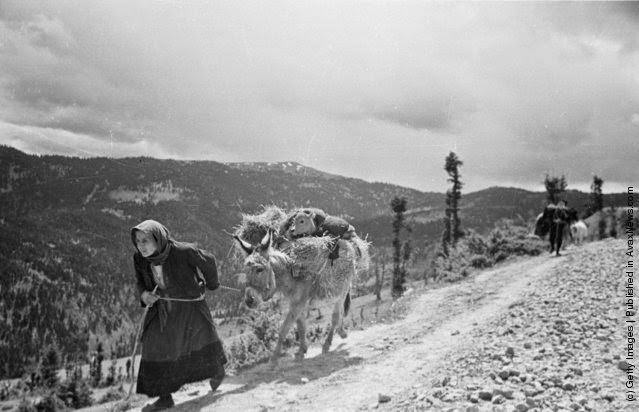

During World War II, Greece was crushed under the boot of German and Italian occupation. The Greek king and his government fled into exile, leaving a massive power vacuum. Into this void stepped the Greek people, who formed powerful resistance groups to fight the invaders. But these groups were not united. They had vastly different ideas about what a free Greece should look like, and they hated each other almost as much as they hated the occupiers.

The largest and most effective resistance force was EAM-ELAS. EAM was the political front, and its military wing, ELAS, was dominated by the Greek Communist Party (KKE). They were organized, ruthless, and incredibly popular with many Greeks who felt abandoned by the old government. Their vision was a socialist republic, free from the monarchy and foreign influence.

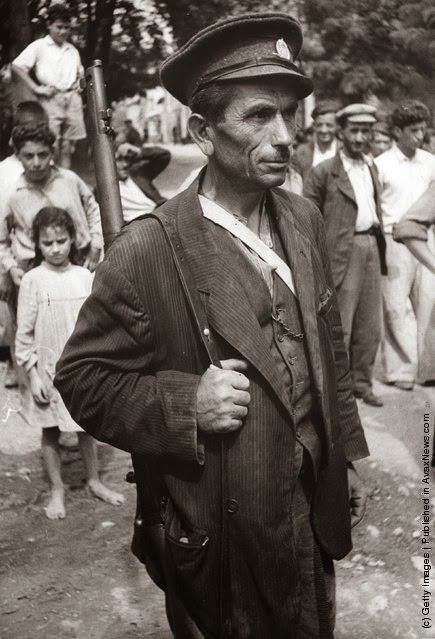

Their main rival was EDES, a smaller, right-leaning nationalist group. They wanted to restore the pre-war republic and vehemently opposed the communists. As early as 1943, with the Germans still occupying the country, these two Greek resistance armies began fighting each other. They were engaged in a pre-civil war, a bloody struggle for who would control Greece the moment the Nazis left.

Read more

The First Shots: The Battle for Athens

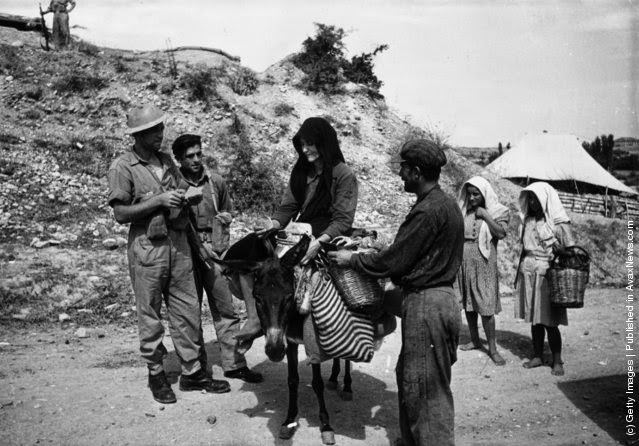

In October 1944, the German army retreated from Greece. British troops landed, not just as liberators, but to ensure the returning Greek king and his government-in-exile would regain control. A shaky “Government of National Unity” was formed, including representatives from all sides, but it was a house of cards. The breaking point came when the new government, backed by the British, demanded that all resistance forces disarm.

ELAS, which controlled most of the country, saw this for what it was: a political move to strip them of their power. They refused. On December 3, 1944, a massive, pro-EAM demonstration filled the streets of Athens. The protest was peaceful until government police opened fire on the unarmed crowd, killing dozens.

Athens exploded. The event, known as the Dekemvriana (December Events), triggered a 37-day street battle for the capital. It was a brutal, close-quarters fight between the communist-led ELAS and the combined forces of the British Army and Greek government troops. British tanks and soldiers fought Greek guerrillas house by house. In the end, the British military superiority was too much. ELAS was defeated in Athens and, in February 1945, was forced to sign the Varkiza Agreement, promising to lay down its arms.

The White Terror

The Varkiza Agreement was supposed to bring peace. It brought the opposite. The deal was completely one-sided. While the communists disarmed, the right-wing militias and security forces did not. What followed was a period known as the White Terror. For over a year, right-wing gangs, often with a nod from the police, hunted down anyone suspected of being a leftist.

Former ELAS members, their families, and anyone associated with the communist cause were targeted. They were arrested, thrown into island prisons, tortured, and murdered. This campaign of terror made it impossible for the KKE to participate in politics safely. When a general election was held in 1946, the communists boycotted it, knowing the vote would be rigged and their supporters would be too afraid to go to the polls. The right-wing, royalist parties won a massive victory.

Faced with political extinction and physical annihilation, the Greek communists saw only one option left. They decided to fight back. They retreated to the mountains of northern Greece and took up arms once again, officially beginning the Greek Civil War in March 1946.

A Global Battlefield

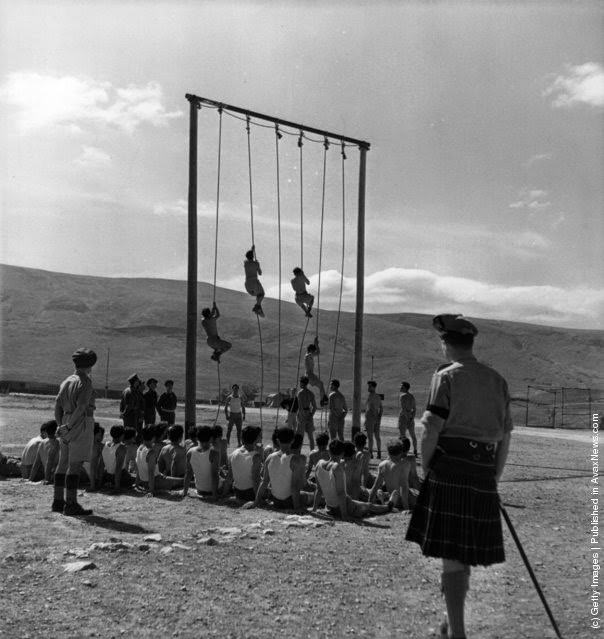

The conflict pitted two new armies against each other. On one side was the Greek National Army (GNA), the official military of the royalist government in Athens. On the other was the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE), the rebuilt guerrilla force of the Communist Party, led by the brilliant commander Markos Vafiadis.

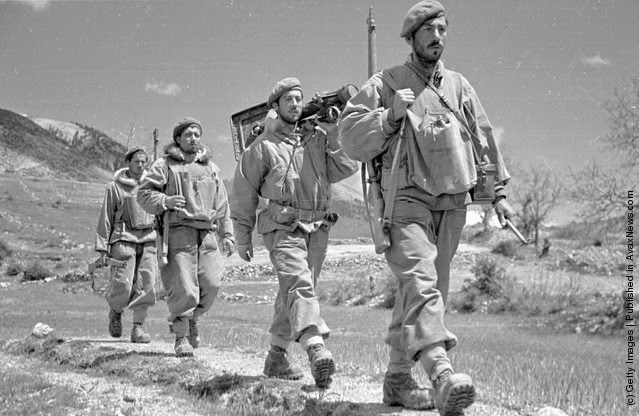

The DSE used the rugged mountains as their sanctuary, launching classic guerrilla raids against government forces. Their fight was fueled by outside help. The new communist states of Yugoslavia, Albania, and Bulgaria, located just across the northern border, provided the DSE with weapons, supplies, and a safe place to retreat and regroup.

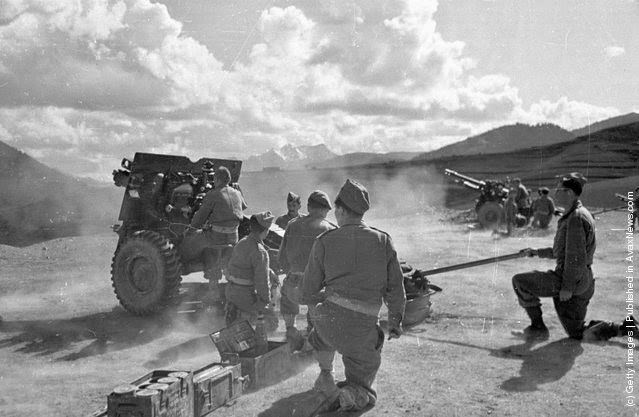

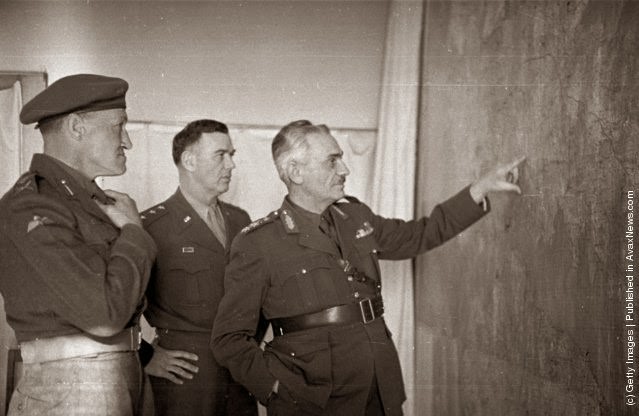

The GNA was initially backed by Great Britain. But by 1947, Britain was economically shattered by WWII and could no longer afford the mission. They informed the United States they were pulling out. This was a critical moment for the West. On March 12, 1947, U.S. President Harry S. Truman went before Congress and announced what would become the Truman Doctrine. He declared that the United States would provide support to “free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation.” Greece was the first test case.

America’s entry changed everything. A flood of U.S. military aid—planes, artillery, and even the chemical weapon napalm—poured into the hands of the Greek National Army. American military advisors arrived to train and direct the GNA’s campaigns. The small, internal Greek conflict was now a full-blown proxy war between the United States and the Soviet sphere of influence.

The Final Act

The massive influx of American aid began to tip the scales. The GNA swelled in size and strength. At the same time, the communists made a critical mistake. They switched from flexible guerrilla tactics to conventional warfare, trying to seize and hold territory like a regular army. This made them a much easier target for the GNA’s superior airpower and artillery.

The final, fatal blow to the DSE came not from the battlefield, but from politics. In 1948, a major split occurred between Yugoslavia’s leader, Josip Broz Tito, and the Soviet Union’s Joseph Stalin. Tito, seeking to assert his independence, decided to cut his ties with the pro-Stalin Greek communists. In July 1949, he closed the Yugoslavian border, cutting off the DSE’s most important supply line and escape route.

The Greek National Army saw its chance. In August 1949, they launched Operation Pyrsos (Operation Torch), a final, massive offensive against the DSE’s last strongholds in the Grammos and Vitsi mountains. Pounded by air strikes and overwhelmed by ground troops, the DSE was crushed. The surviving fighters fled across the border into Albania, and the Greek Communist Party announced a “temporary” ceasefire, effectively ending the war.