After World War II, Eastern Europe’s architecture shifted under the push of rebuilding and communist ideas. Socialist Modernism drove this change in the Communist bloc. Nations launched large building efforts to highlight new social and political ideals. Key traits included usefulness, grand size, and long-lasting design. Brutalism stood out in this era. It blended hopes for a better society with real-world factory methods.

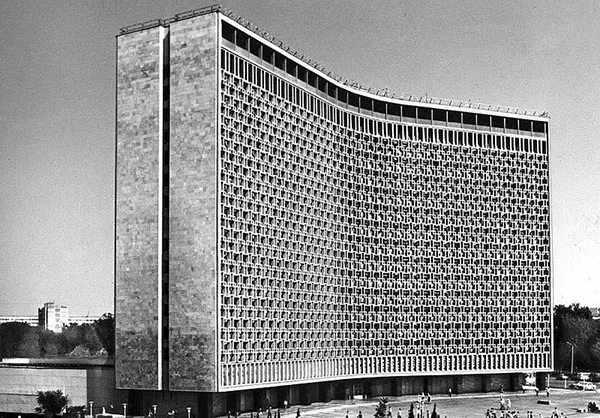

Socialist Modernism varied by place but followed state rules tied to socialist aims. It borrowed from the International Style and Modernism. Those stressed clear thinking, straight edges, and plain surfaces without extras. In the Eastern Bloc, builders twisted these to fit group living under socialism. Structures built community spirit. They displayed new machines and tools. They also pushed back against old times and Western ways.

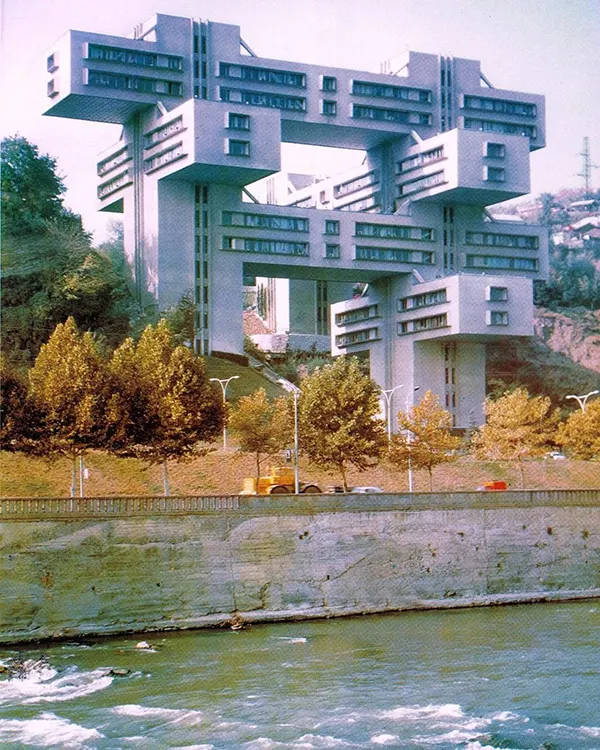

Brutalism linked closely to Socialist Modernism and reshaped city views. The name comes from “béton brut,” French for raw concrete. Designs featured huge forms, open materials, and sharp angles. Concrete ruled as the main stuff. It cost little and came easy. It stood for toughness and a fresh start away from fancy past styles linked to rulers or rich classes.

Read more

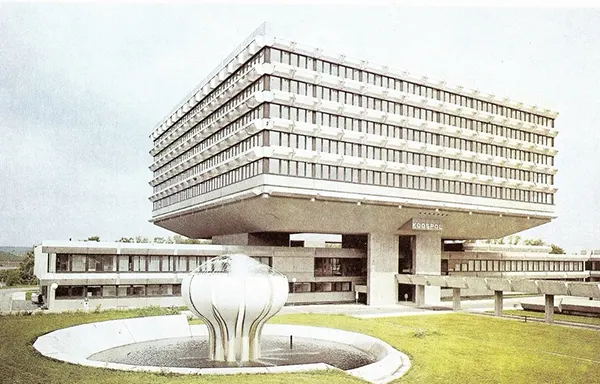

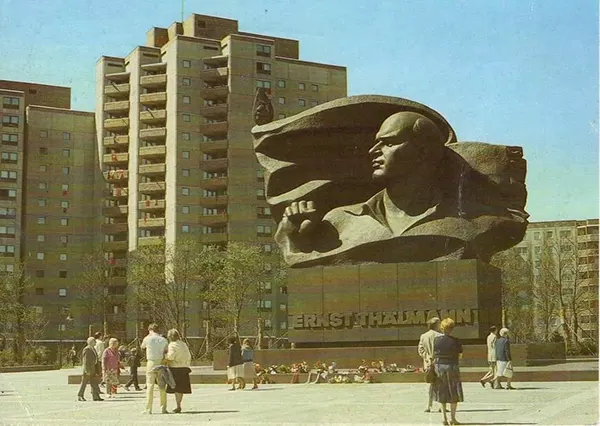

Big projects filled cities like Belgrade, Sofia, East Berlin, Moscow, Minsk, and Kyiv. Housing towers, arts halls, work sites, and statues went up fast. State planners picked architects who worked in systems favoring the same looks and quick builds. Local flavors sneaked in through folk designs, carved fronts, or wild supports. These mixed home roots with party messages.

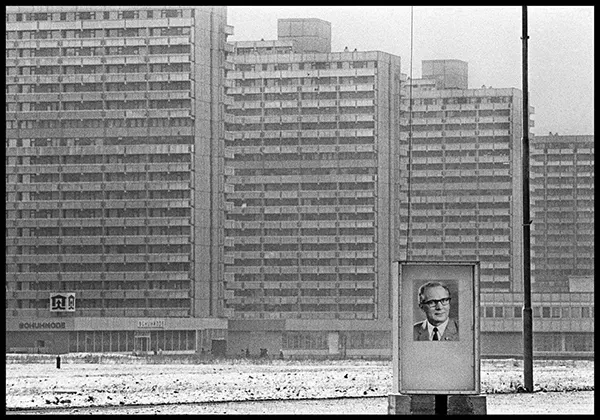

Construction hit vast levels. Prefab concrete slabs formed whole blocks, put together using Soviet plans. Microrayons served as full living zones. They held homes plus schools, health spots, and group areas. This setup matched socialist views on organized shared days. Public spots like offices, stages, and markers took on oversized shapes and strong lines. They aimed to show control and endless strength.

In Belgrade, brutalist works define the skyline with their raw edges and bold scales. The Karaburma Housing Tower rises as a sharp triangle. Built in 1963 by architect Rista Sekerinski, it earns the nickname Toblerone from its pointed form. Photos reveal its concrete sides catching light in jagged patterns against the sky. Another standout is Blok 61 in New Belgrade. This residential cluster uses stacked blocks and open spaces. Images capture the repeating units and wide courts meant for daily life. The Genex Tower, or Western City Gate, splits into two linked pillars. Designed in the 1970s, it towers over roads with its split shape and exposed beams. Close-up shots highlight the rough texture of its concrete skin.

Sofia holds examples of brutalist towers that blend into dense neighborhoods. Tower Blocks 67-68 in the Druzhba-1 area show modified prefab designs from the BS-69 series. Built in the late 1960s, they feature tall slabs with grid patterns on the fronts. Photos from ground level emphasize their height and the shadows cast by overhanging edges. The high-rise blocks in Iskar district use raw concrete for stark lines. These structures include folk-inspired details in the panel joints. Wide-angle images display clusters of these towers rising above streets, with people for scale.

East Berlin’s brutalist sites mix Cold War tension with space-age forms. The Pallasseum in Schöneberg stacks apartments in a massive block. Completed in 1977, it curves around an inner yard. Aerial photos show its layered roofs and the grid of windows punched into concrete walls. The Bierpinsel in Steglitz looks like a tower from the future. Built in 1976, it flares out at the top with bold colors on the concrete. Night shots capture its lit form standing alone against dark skies. The Mäusebunker in Lichterfelde serves as a former lab with sloped walls and vents. From the 1970s, its bunker-like shape hides underground levels. Ground photos reveal the angled concrete planes and small openings.

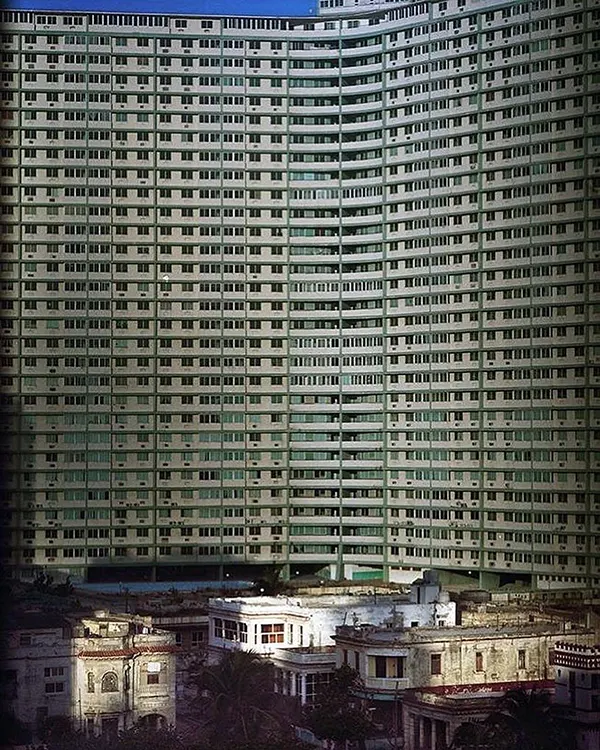

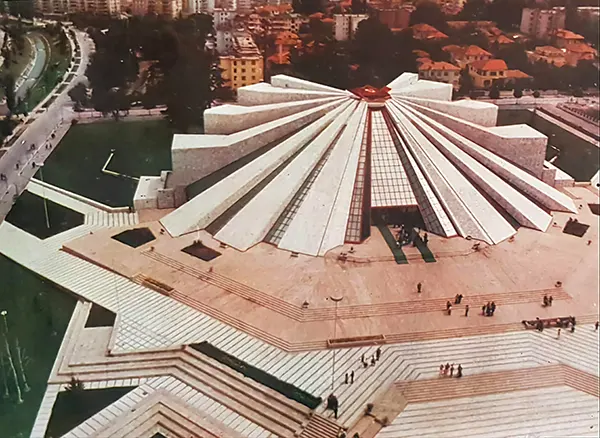

Moscow features circular and market designs in brutalist style. The Residential Building on Bolshaya Tulskaya Street forms a full ring. Known as the House of Atomists or Ship Building, it went up in the 1970s. Photos from inside the circle show the curved walls enclosing a green court. Danilovsky Market spreads under a dome of concrete ribs. Architects Felix Novikov and others finished it between 1979 and 1986. Overhead images highlight the star-like roof and open interior for stalls.

Minsk preserves microrayons and public halls from the Soviet years. The Micro District Vostok arranges towers in planned groups. Architects Viktor Anikin and others built it in the 1970s. Street-level photos display the tall slabs with balcony rows and paths between. Cinema Moskva stands with a wide front and sloped roof. Viktor Kramarenko and team completed it in 1980. Exterior shots focus on the entrance canopy and glass mixed with concrete.

Kyiv showcases museum and library towers in raw forms. The Ukrainian House, once the Lenin Museum, occupies a central spot. Vadym Hopkalo designed it from 1978 to 1982. Facade photos stress the stepped levels and column grids. The National Library headquarters rises as a windowless stack. In Demiivka, its brutalist tower holds books in secure layers. Close images show the plain concrete sides and secure doors.

A former presidents library in Illinois looks like it will fit right in.

Commie urban planning differed vastly in theory and practice.

While some praise the concept, the reality of living in these large housing estates, like those I experienced, was far from the “ultimate urban planning scenario.”

Good public transit was a necessity, not a luxury, due to low car ownership. But even this transit was often overcrowded, forcing long walks and wait times, especially at the twilight of communism as the economy of my country and most of the Soviet Bloc was collapsing.

Living in a massive, quickly-built prefab estate meant growing up in a “moonscape” of mud and construction, sometimes literally having dirt spray-painted green for official party visits. The buildings themselves were shoddy. I remember rainstorms would usually cause our roof to leak, as we lived on the top floor.

These estates, often built on city outskirts, failed to provide nearby jobs, remaining monolithic, isolated suburbs. The ironically same critiques that many have for Western suburbs.

After the fall of communism, they quickly deteriorated, becoming unsafe centers for crime and drug use after dark. My estate was home to a pretty violent football hooligan group.

Older housing types, like the Khrushchovkas my parents lived in, weren’t much better. Despite housing a mix of classes, they suffered from high crime, fueled by issues like rampant alcoholism.

The pervasive atmosphere of distrust, where any neighbour could be an informant, created a deep sense of loneliness among adults.

Even the idea of having informants and members of the security service in those places didn’t actually mean safer environs. Inspite of officially going after illegal alcohol production, at my parents estate, the local alcoholics would peddle booze openly even to the knowledge of the local secret police snitch.

Ultimately, my memories of growing up in a “commie block” are of an unsafe, dehumanizing, and inaccessible environment—many buildings, with their central staircases, lacked basic accessibility for things like wheelchairs or even baby strollers.

Crime was rampant, substance abuse often in full view of everyone.

Seems quite similar to the housing projects we built in the states during the same time. They built them in every medium to large city. I guess the main difference being in the urban core for the most part. But while the idea of creating a bunch of housing is good, it didn’t seem like there was a thoughtful effort to support the environment in the building nor properly maintain the structures

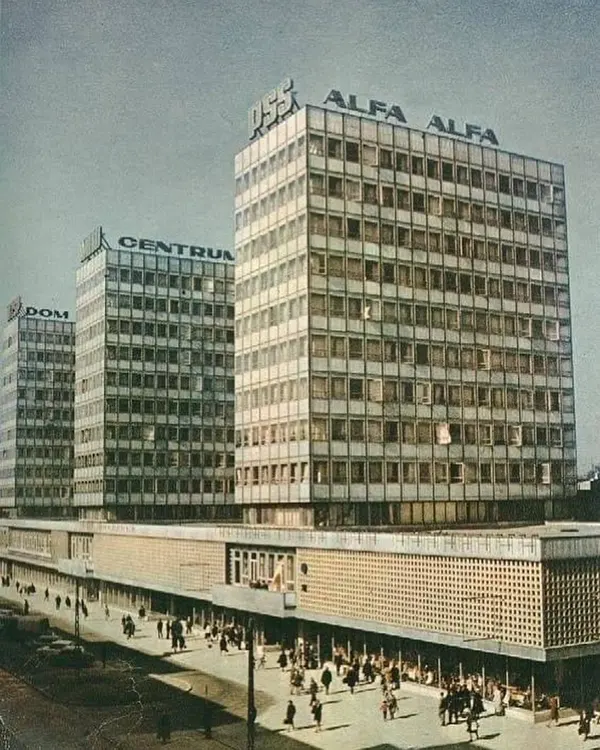

On a more fun note, the Alfa buildings shown are from my hometown and are personally one of my favourite brutalist buildings in the city.