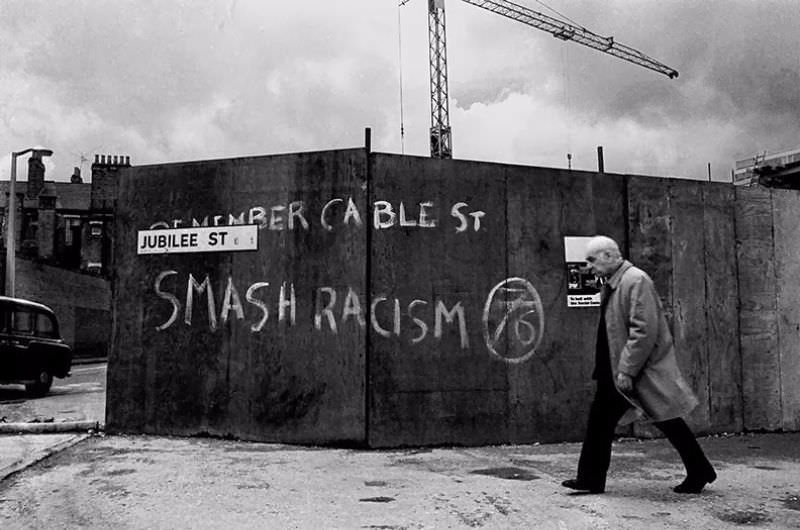

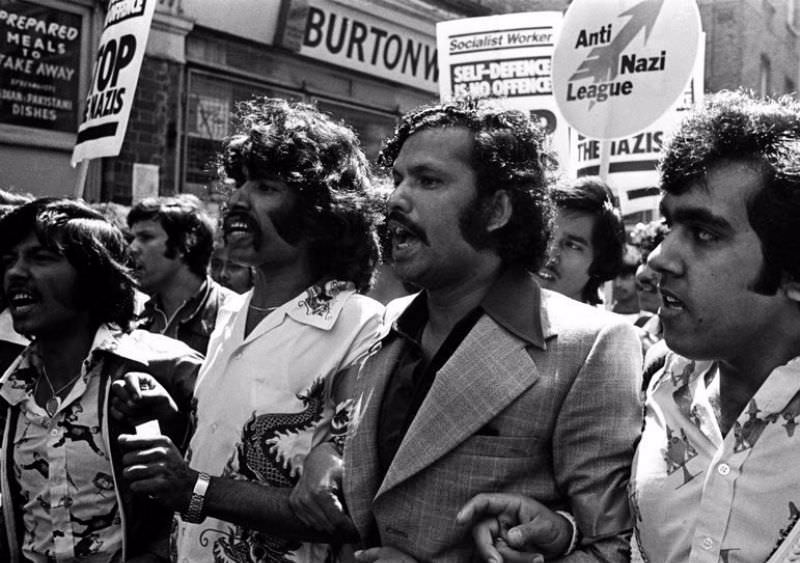

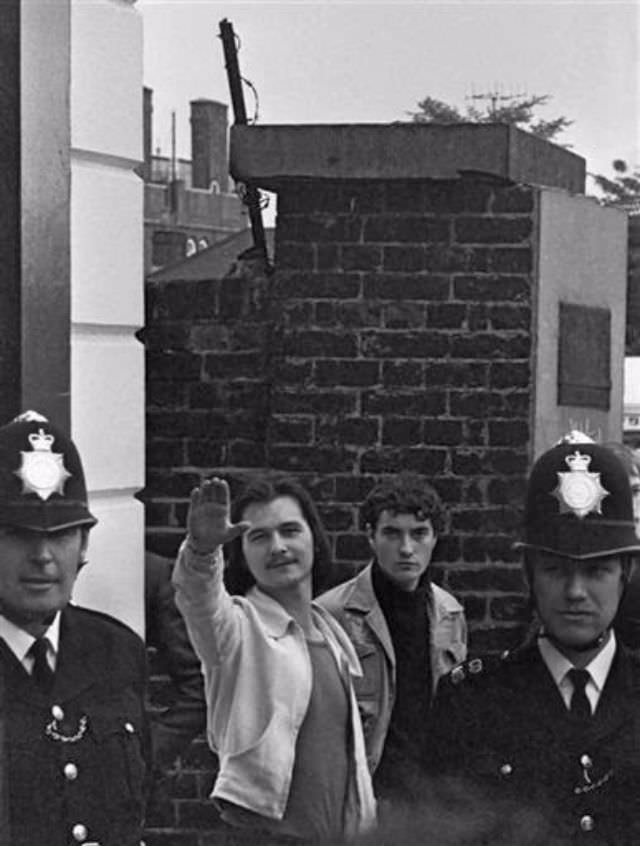

In the mid-1970s, Britain was experiencing significant social and political tension. Economic decline and rising unemployment created a fertile ground for extremist politics. The National Front, a far-right political party with a strong anti-immigrant and racist platform, was gaining noticeable support. In local elections, the party was drawing a growing number of votes, and their marches often resulted in street-level violence against immigrant communities. It was in this environment that a powerful counter-movement, uniting musicians and fans, was born.

The Spark of a Movement

The catalyst for Rock Against Racism (RAR) came from within the music world itself. In August 1976, during a concert in Birmingham, famed guitarist Eric Clapton made comments from the stage supporting the anti-immigration politician Enoch Powell. This incident, along with similar nationalist statements by other rock figures, outraged many artists and fans who saw rock and roll as being rooted in Black musical traditions.

In response, a group of activists, including photographer Syd Shelton and musician Red Saunders, penned a letter to the music press. The letter directly challenged Clapton’s statements and called for rock music to be a force against racism. This letter led to the formation of Rock Against Racism. The organization adopted a simple, powerful slogan: “Love Music, Hate Racism,” and created an iconic logo featuring a black star and a white star joined together.

Read more

Uniting Punk and Reggae

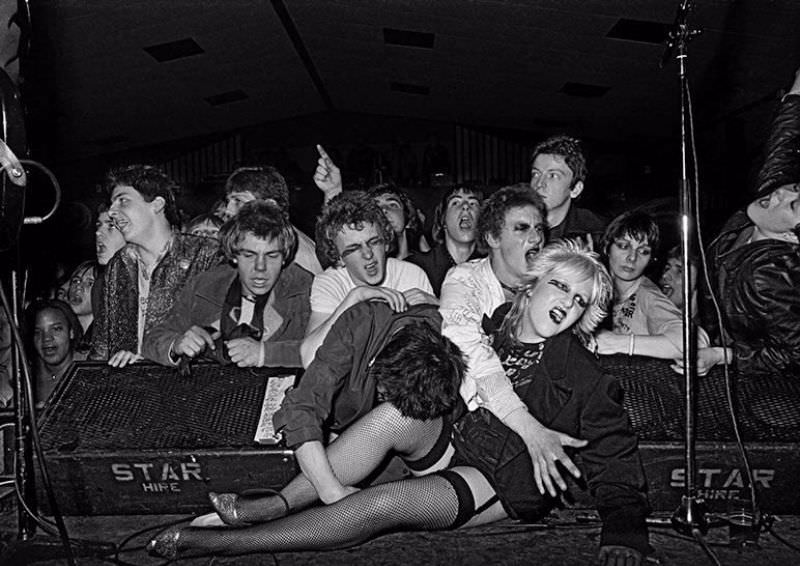

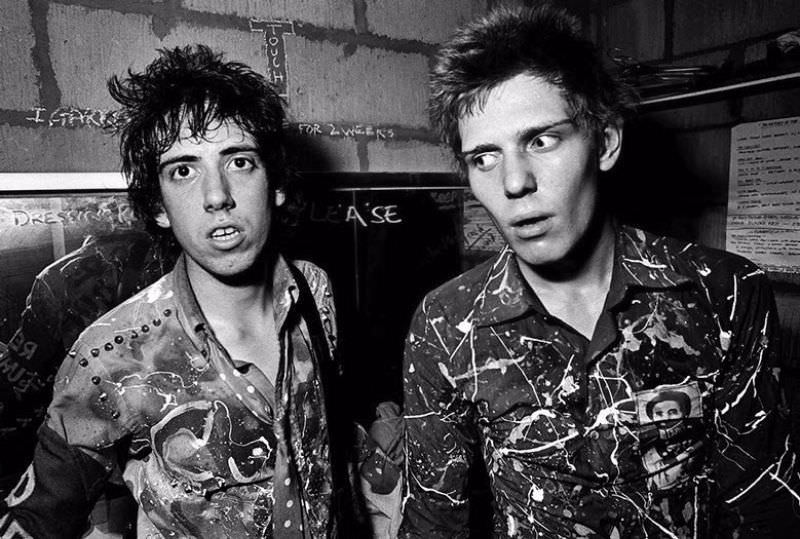

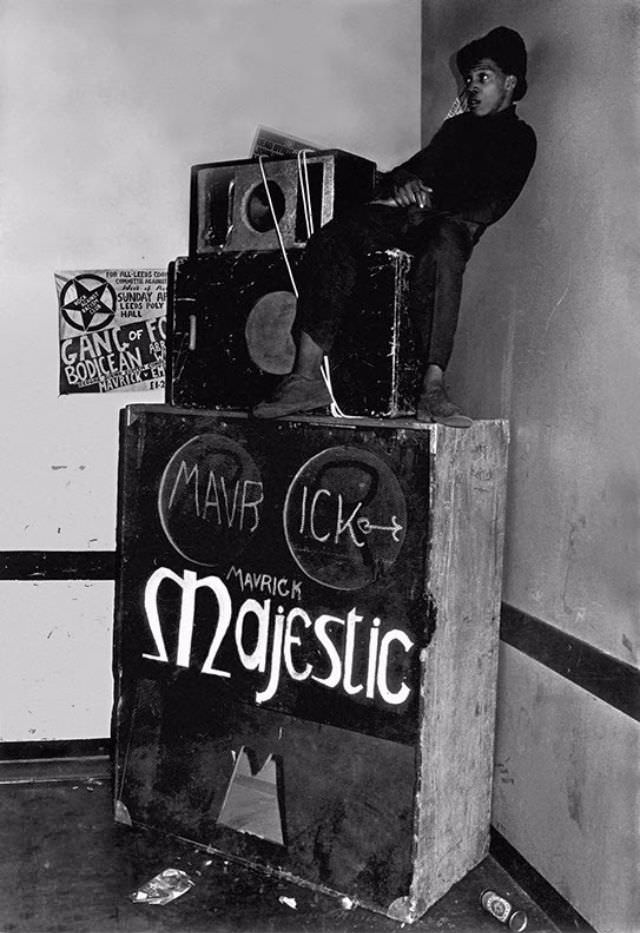

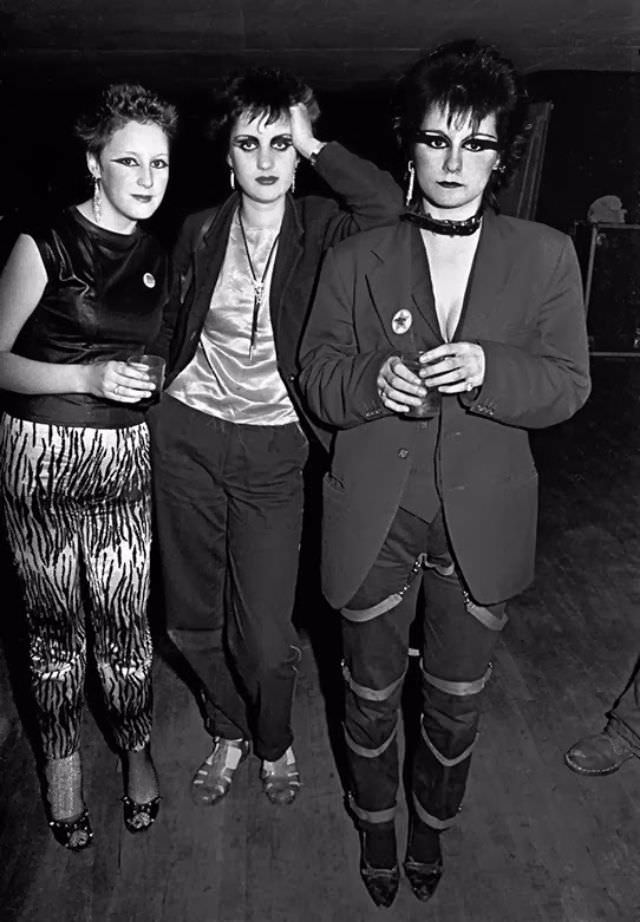

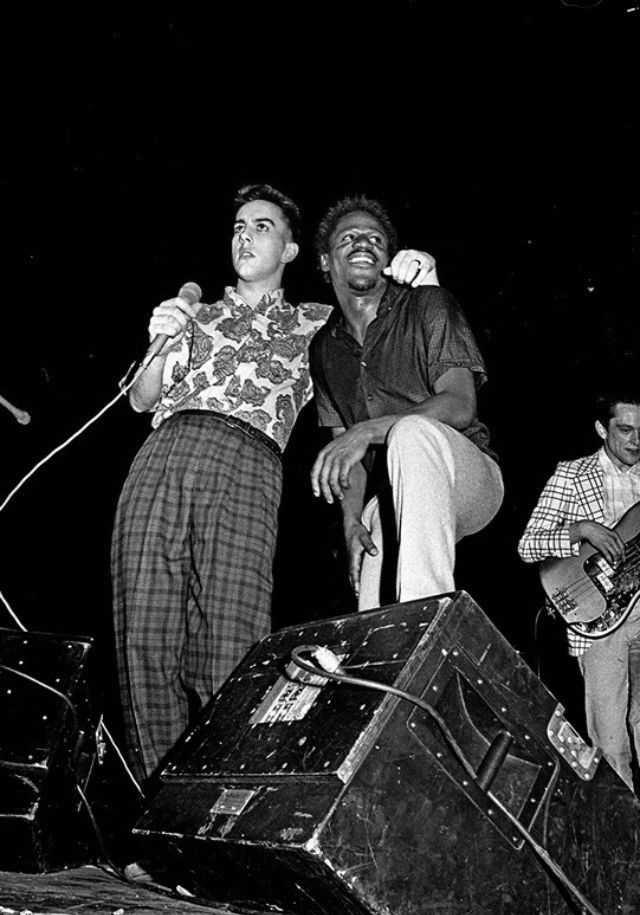

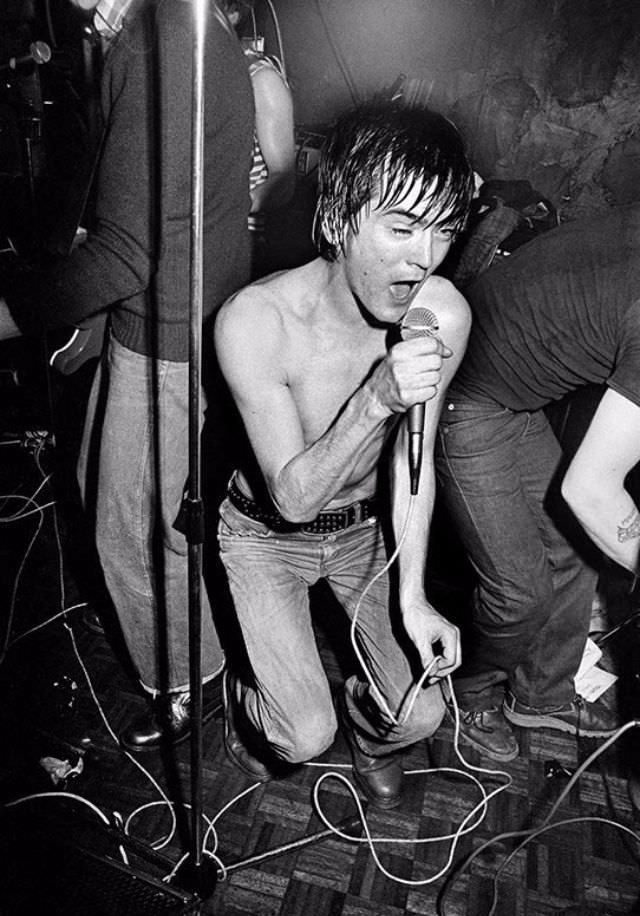

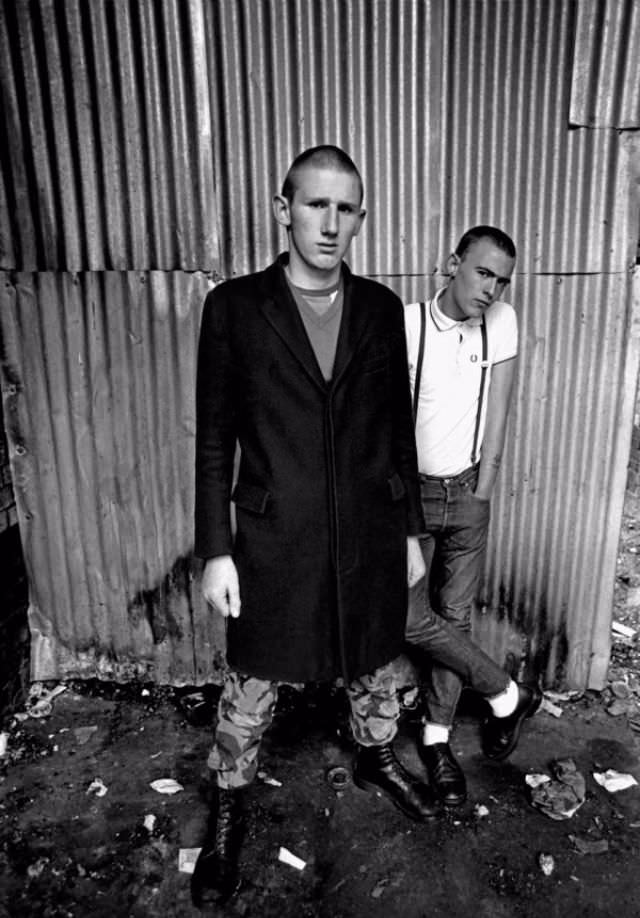

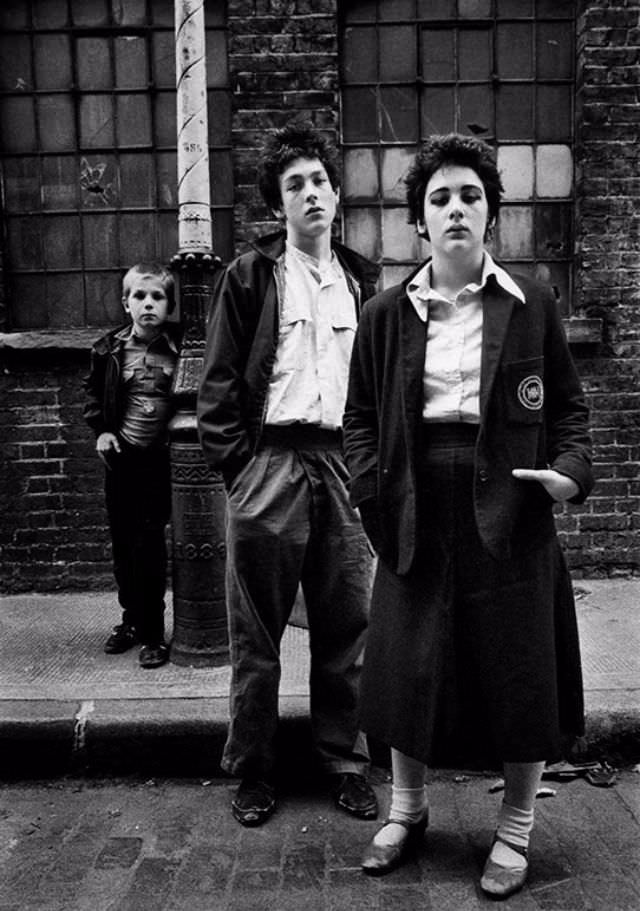

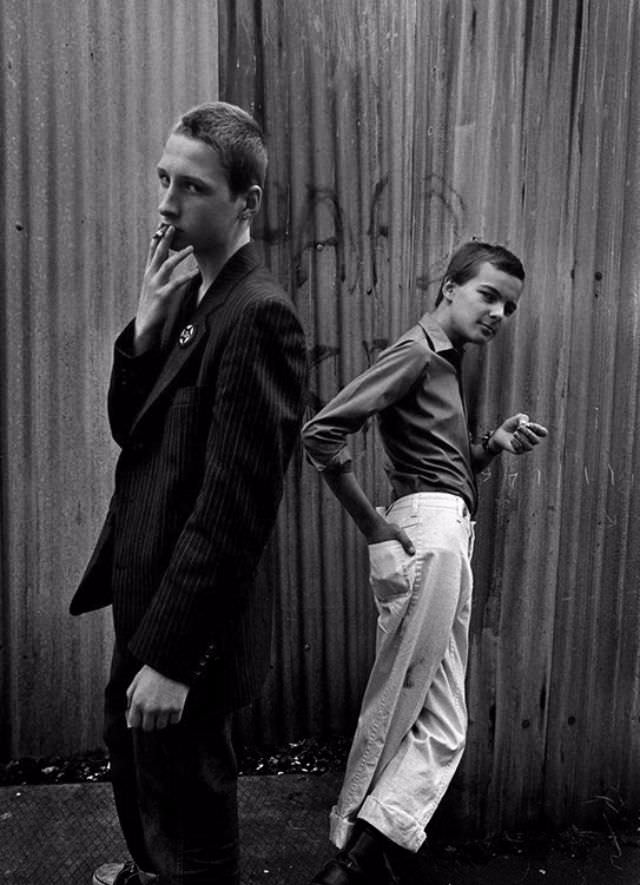

From its inception, RAR’s strategy was to use the energy of live music to bring young people from different racial backgrounds together. The movement deliberately created concert bills that featured both punk rock bands and reggae groups on the same stage. This was a radical idea at the time, as the fan bases for these two genres were often seen as separate.

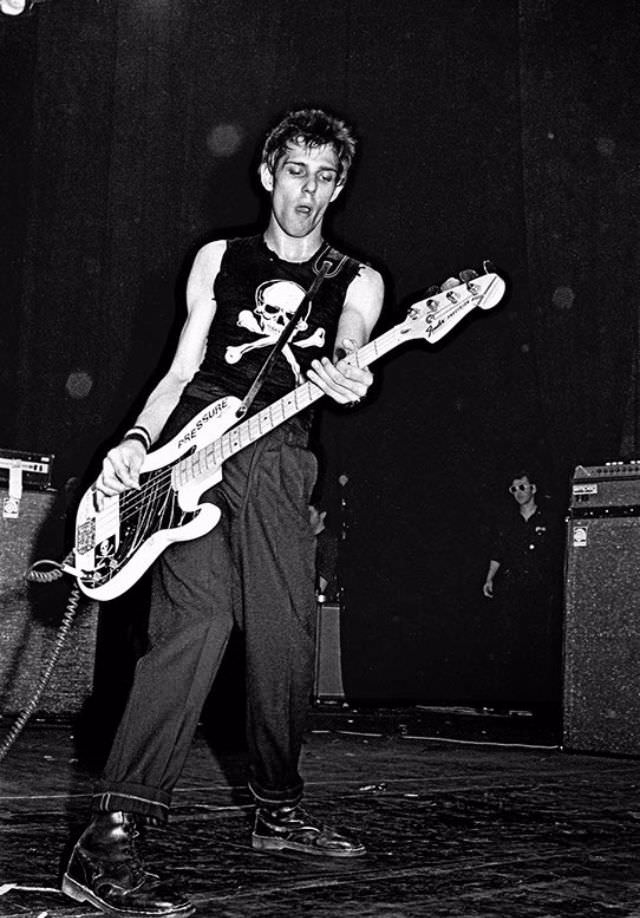

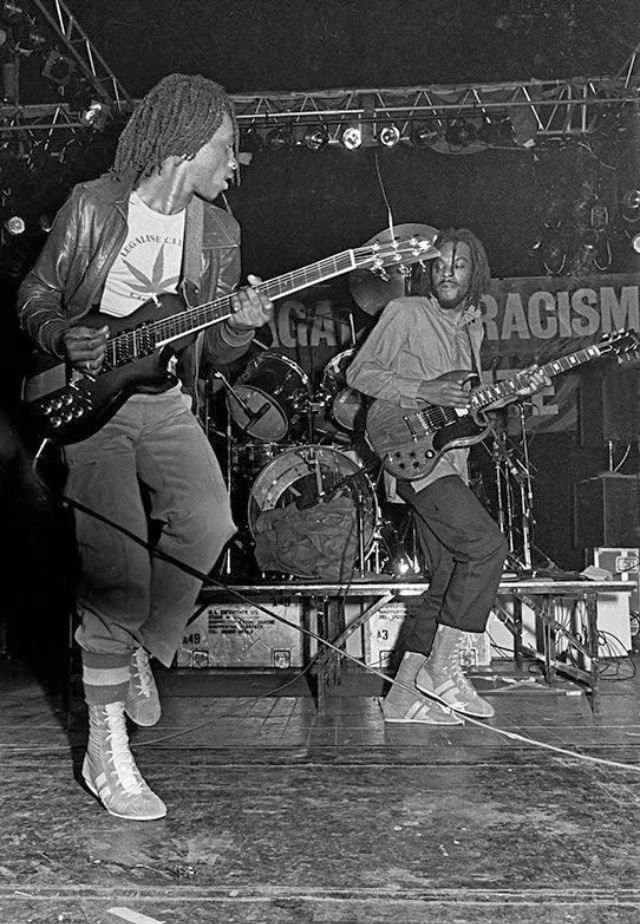

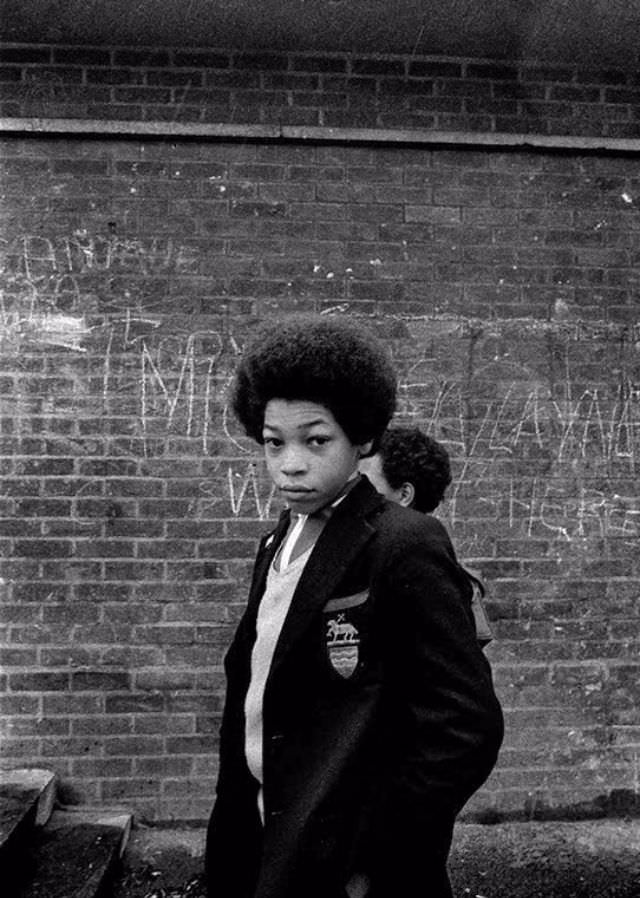

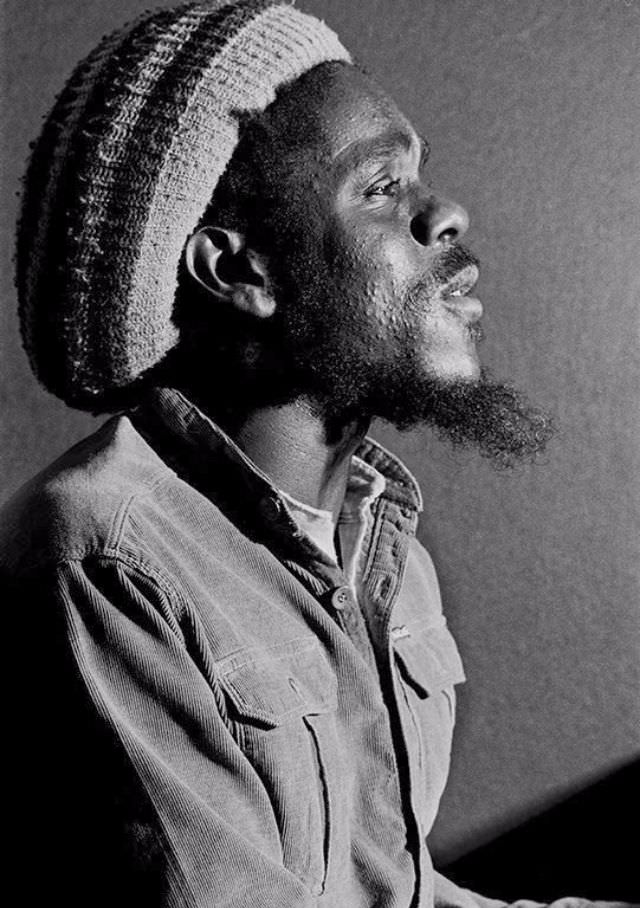

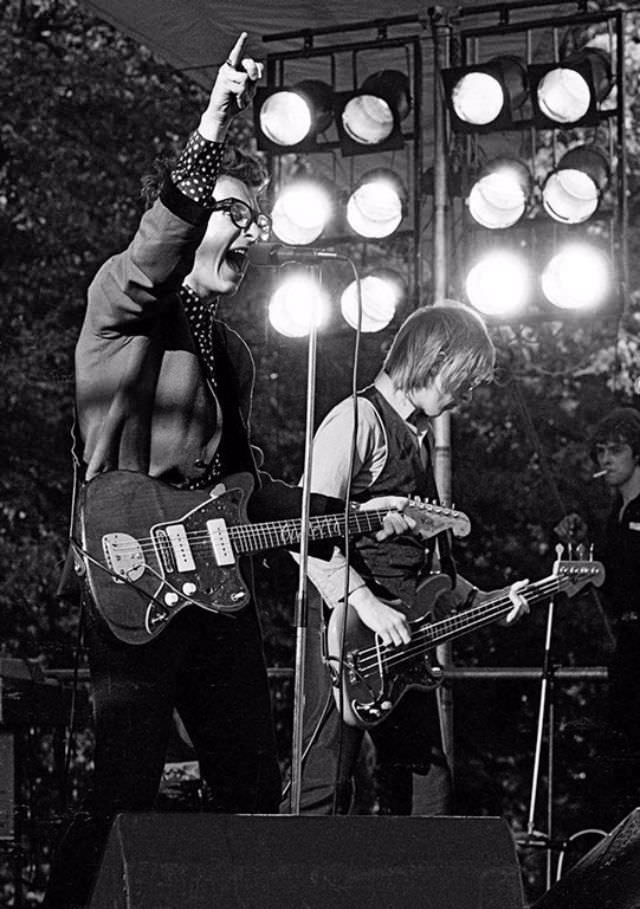

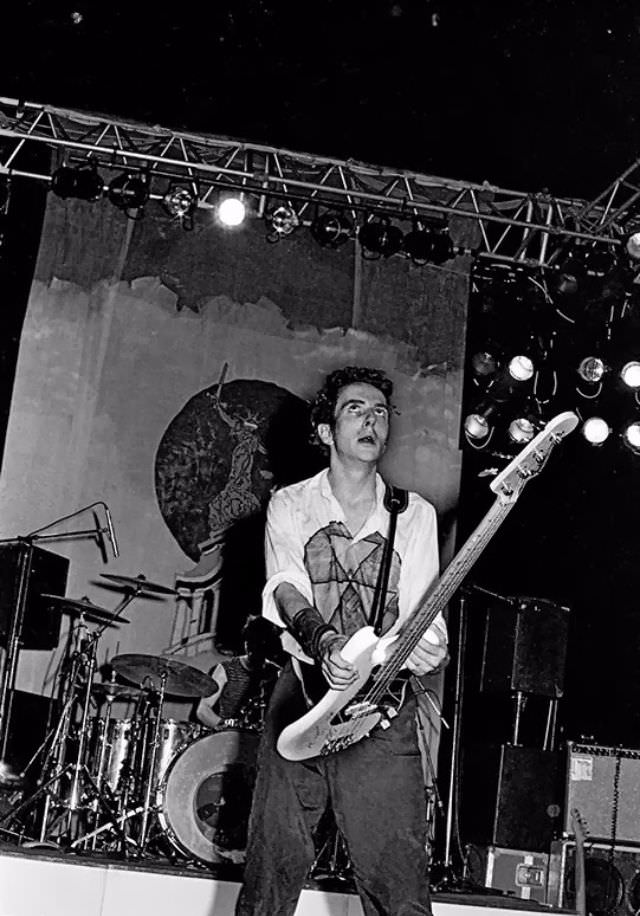

Punk bands like The Clash, Sham 69, and the Tom Robinson Band played fast, loud, and politically charged music that voiced the anger and frustrations of working-class youth. Their lyrics often tackled issues of unemployment, police harassment, and social decay. Reggae bands, many of them with roots in Britain’s Caribbean communities, brought a different sound. Groups like Steel Pulse, Aswad, and Misty in Roots used their music to address issues of racial injustice, cultural identity, and the struggles of living as Black Britons. By placing these bands on the same stage, RAR created a shared cultural space where Black and white youth could unite against a common enemy.

The Carnival Against the Nazis

The movement’s most significant event took place on April 30, 1978. Billed as the “Carnival Against the Nazis,” it was a massive concert and march held in London. The day began with a march from Trafalgar Square to Victoria Park in the East End, an area with a large immigrant population and a history of anti-fascist resistance. An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 people participated in the march and concert.

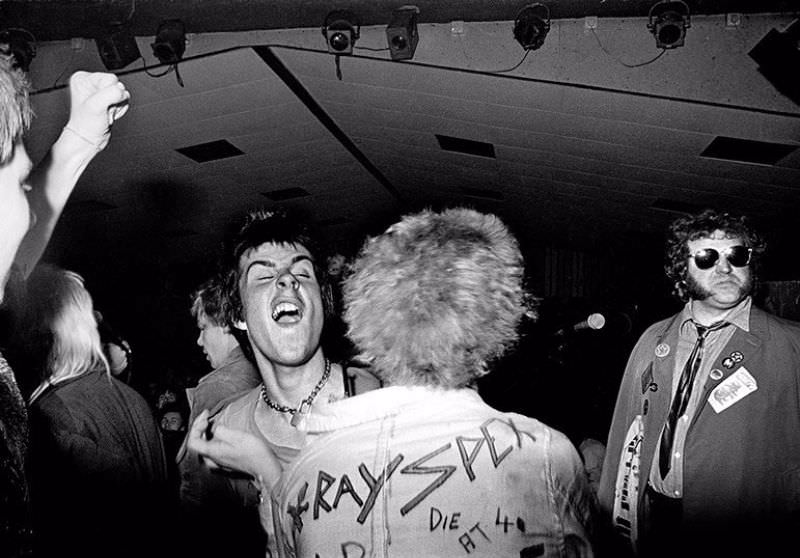

The lineup for the Victoria Park concert was a showcase of the RAR ideal. The Clash, one of the biggest punk bands in the country, headlined the event. Also on the bill were the Tom Robinson Band, known for their anthem “Glad to Be Gay”; Steel Pulse, a reggae band from Birmingham; and X-Ray Spex, a punk band fronted by the multiracial singer Poly Styrene. The event demonstrated the power of music to mobilize a large, multicultural audience in a direct political statement against the National Front and the racism it represented