Stretching 215 miles on its journey to the sea, the River Thames has always been London’s vital artery, shaping its history and serving as a crucial route for trade and transportation for centuries. In the early decades of the 20th century, the Thames flowing through London was a dynamic and often gritty scene, a hard-working river at the heart of a global empire, very different from the river many see today.

A Working River: Commercial Hub

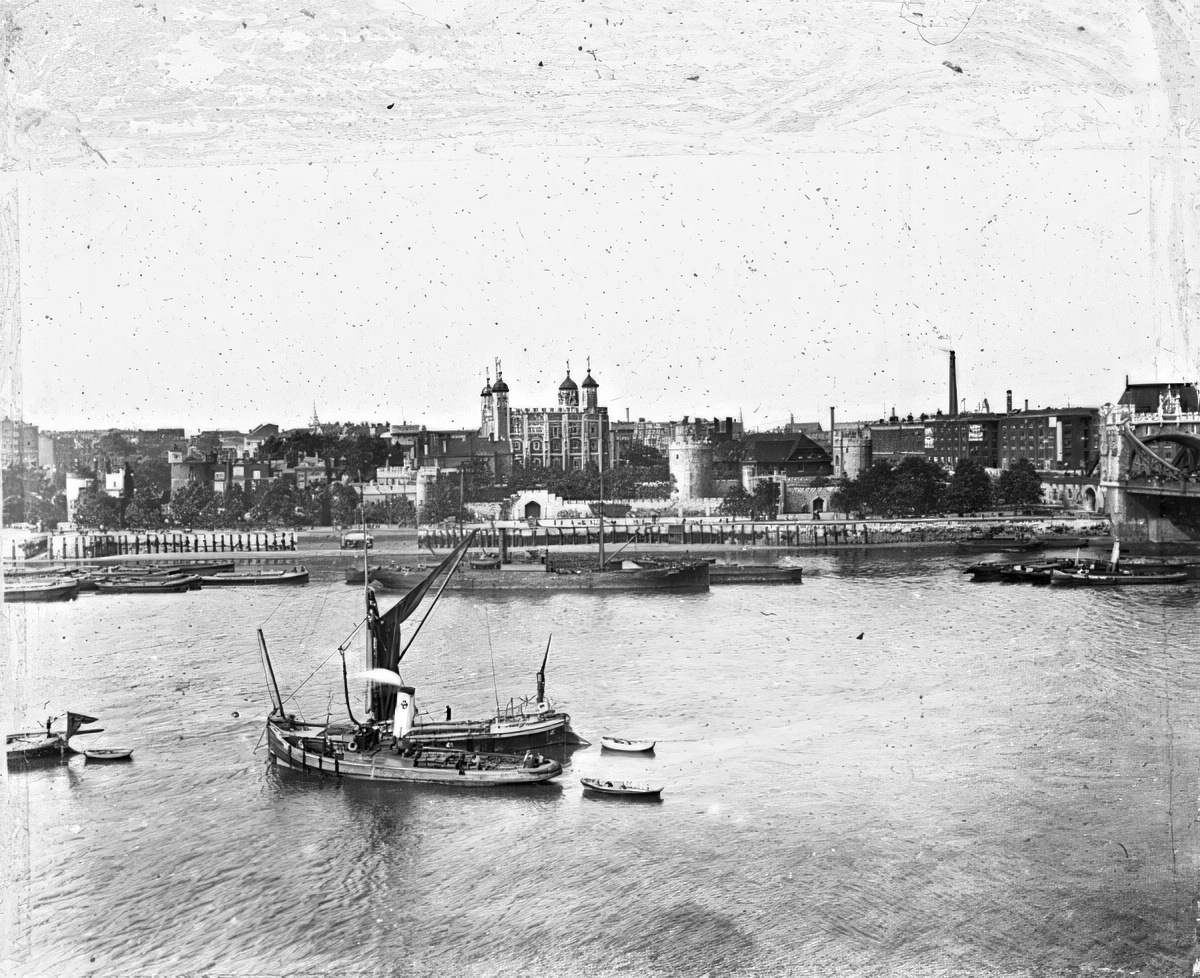

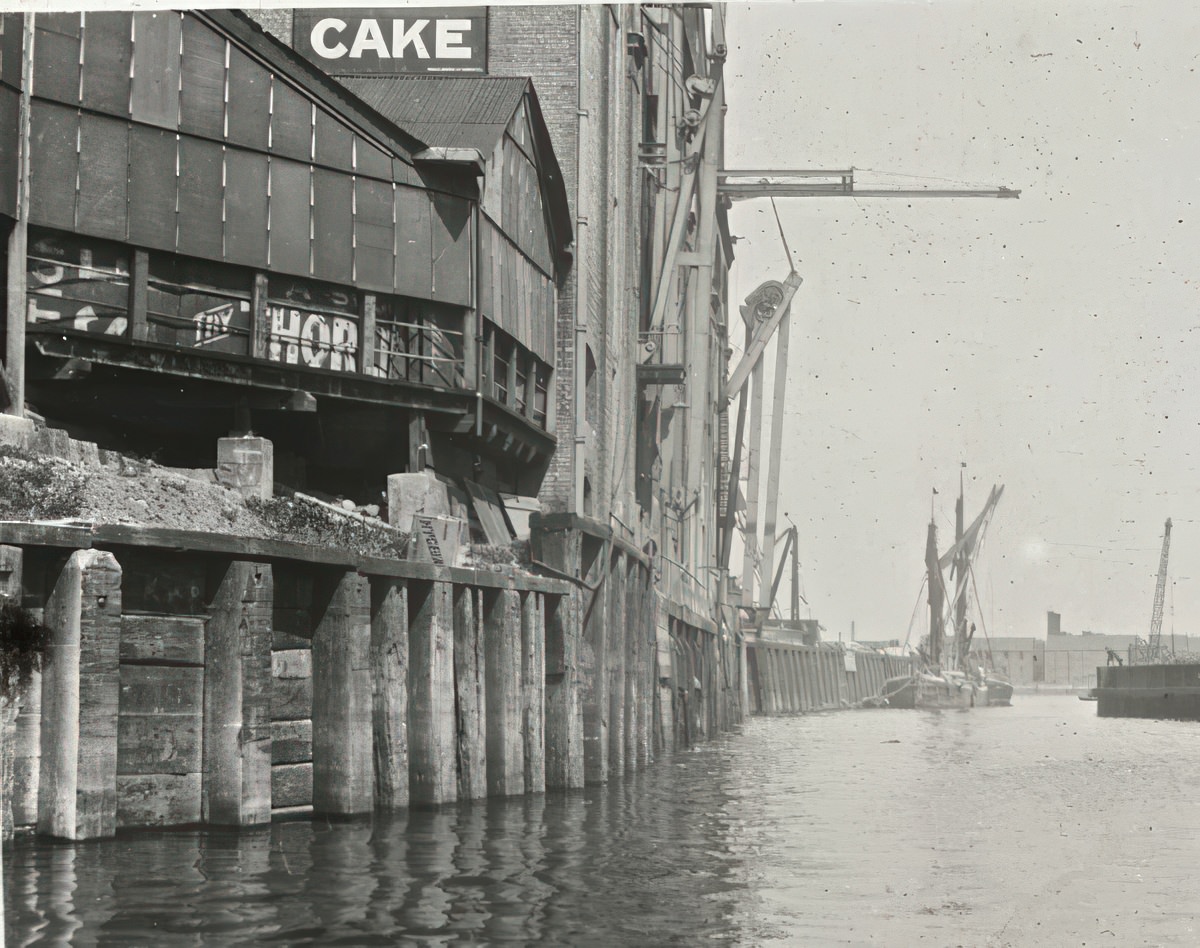

The early 1900s saw the Port of London, centered on the Thames, operating as one of the busiest ports in the world. The stretch of river downstream from London Bridge and Tower Bridge teemed with commercial vessels. Ocean-going steamships and sailing ships (though declining), coastal freighters, fleets of flat-bottomed ‘barges’ and ‘lighters’ used for moving goods between ships and shore, and powerful ‘tugboats’ all jostled for space on the water. The riverbanks, particularly downstream towards the east, were lined with extensive dock systems – places like the Surrey Docks, the London Docks, the West India Docks, and the Royal Docks. These were hives of activity where thousands of dockworkers loaded and unloaded immense quantities of cargo: timber from Scandinavia, coal from the north of England, grain from North America, tea from India, wool from Australia, manufactured goods, and raw materials essential for industry. Skilled ‘lightermen’ expertly navigated their unpowered barges, loaded with cargo, through the busy river traffic, often using only the tide and long oars or poles.

Read more

The River’s Appearance and Condition

The Thames within London during this era was very much an urban river shaped by industry and the city itself. Below Teddington Lock (the traditional limit of the ‘tidal’ Thames), the river’s water level rose and fell twice daily with the ocean tides. While the water quality was considerably better than in the mid-19th century – thanks to engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s revolutionary ‘sewer system’ built from the 1860s onwards, which intercepted much of the city’s raw sewage after the infamous “Great Stink” of 1858 – the river was far from pristine. Industrial discharges, runoff from streets, and the constant disturbance from boat traffic often made the water appear murky and brown. London’s notorious fogs and smog (“pea soupers”), caused by coal smoke mixing with natural fog, frequently descended upon the river, reducing visibility dramatically and adding to the atmosphere. Upstream from Teddington, the ‘non-tidal’ Thames, managed by a system of 44 ‘locks’, flowed more gently and was generally clearer.

Crossing the Thames: Bridges

Connecting the sprawling northern and southern halves of London were numerous bridges, critical links for road and rail traffic. Several iconic structures spanned the Thames in the early 20th century. ‘London Bridge’ itself, located on a site used for a river crossing since Roman times around 2,000 years ago, was then a stone-arched bridge completed in 1831 (later replaced by the current modern structure). Downstream stood the unmistakable ‘Tower Bridge’, completed in 1894, whose central sections (bascules) could be raised to allow tall ships to pass into the Pool of London. Other important crossings included Blackfriars Bridge, Southwark Bridge, Waterloo Bridge (an earlier version designed by John Rennie), Charing Cross Railway Bridge, and Westminster Bridge near the Houses of Parliament.

Life Along the Banks

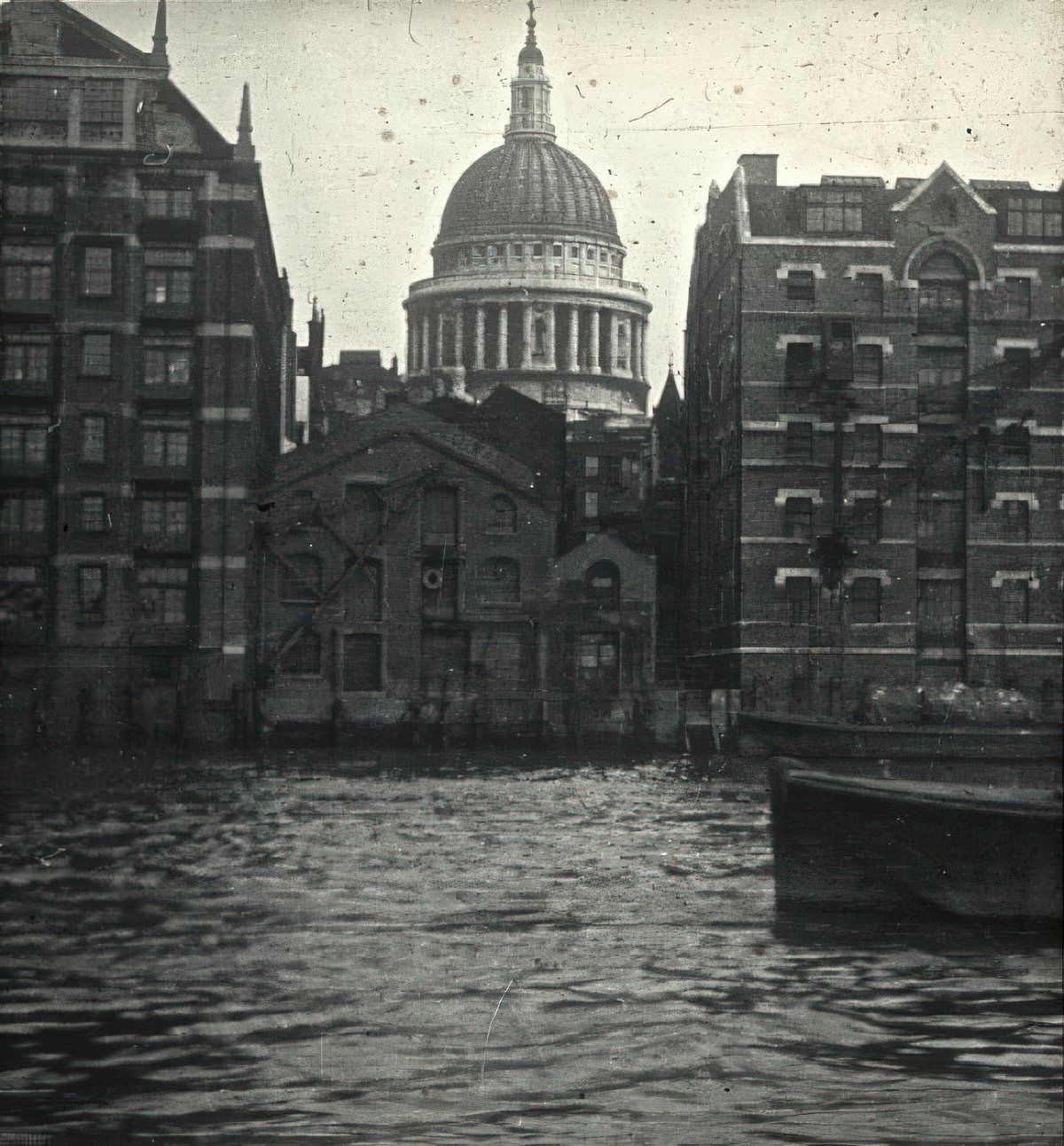

The character of the Thames riverbanks varied greatly. In the east, towards the estuary, vast areas were dominated by docks, wharves, warehouses, ship repair yards, and riverside industries. Further west, within central London, the river’s edge had been significantly reshaped by the construction of the great Victorian ‘embankments’: the Victoria Embankment on the north side, and the Albert and Chelsea Embankments on the south. Built largely in conjunction with the sewer system, these stone walls created defined river edges, wide public walkways (promenades), and major roadways, replacing the often muddy or chaotically developed banks of earlier centuries. From the river or its embankments, many of London’s key landmarks were prominent, including the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben, Cleopatra’s Needle, Somerset House, the Tower of London, and views towards St. Paul’s Cathedral.