The Soviet Union was built on a monumental promise: to create the world’s first workers’ paradise. For its citizens, this meant a life of extraordinary predictability. The state was a constant presence from cradle to grave, providing a job, a home, education, and healthcare. It was a social contract that offered total security. This security, however, came at a tremendous cost. The life of an average Soviet citizen was a constant negotiation between the state’s rigid control and the universal human desire for choice, comfort, and personal freedom.

The All-Providing State

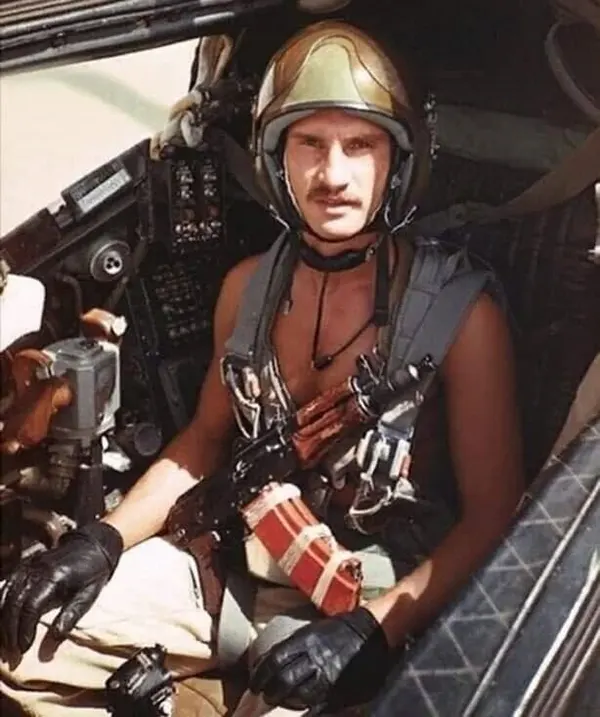

From the moment a person was born in a state-run hospital, their life was mapped out for them by the Communist Party. The state was the ultimate provider. Education was completely free, from kindergarten all the way through university. Access to higher learning was competitive but based on academic merit, opening doors for talented individuals from all backgrounds. Healthcare was also a universal right, delivered free of charge through a massive network of state clinics and hospitals.

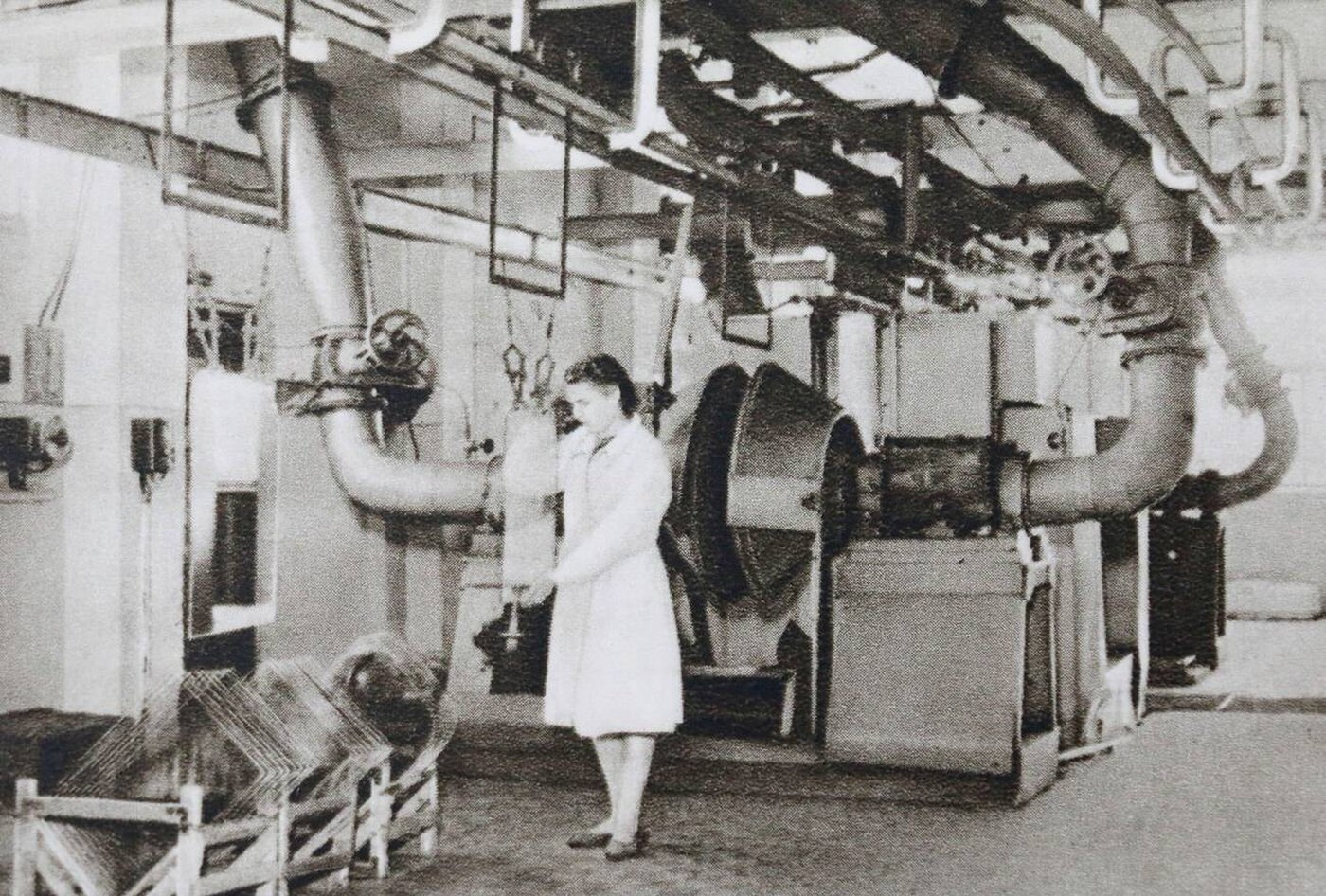

The biggest promise of all was guaranteed employment. In the Soviet system, unemployment officially did not exist. The state was the only employer, and every citizen was entitled to a job. This eliminated the fear of being laid off, but it also eliminated choice. You often worked where the state assigned you, in a job you might keep for your entire life, whether you liked it or not. The concept of “job satisfaction” was a foreign luxury.

Read more

Life in the Kommunalka

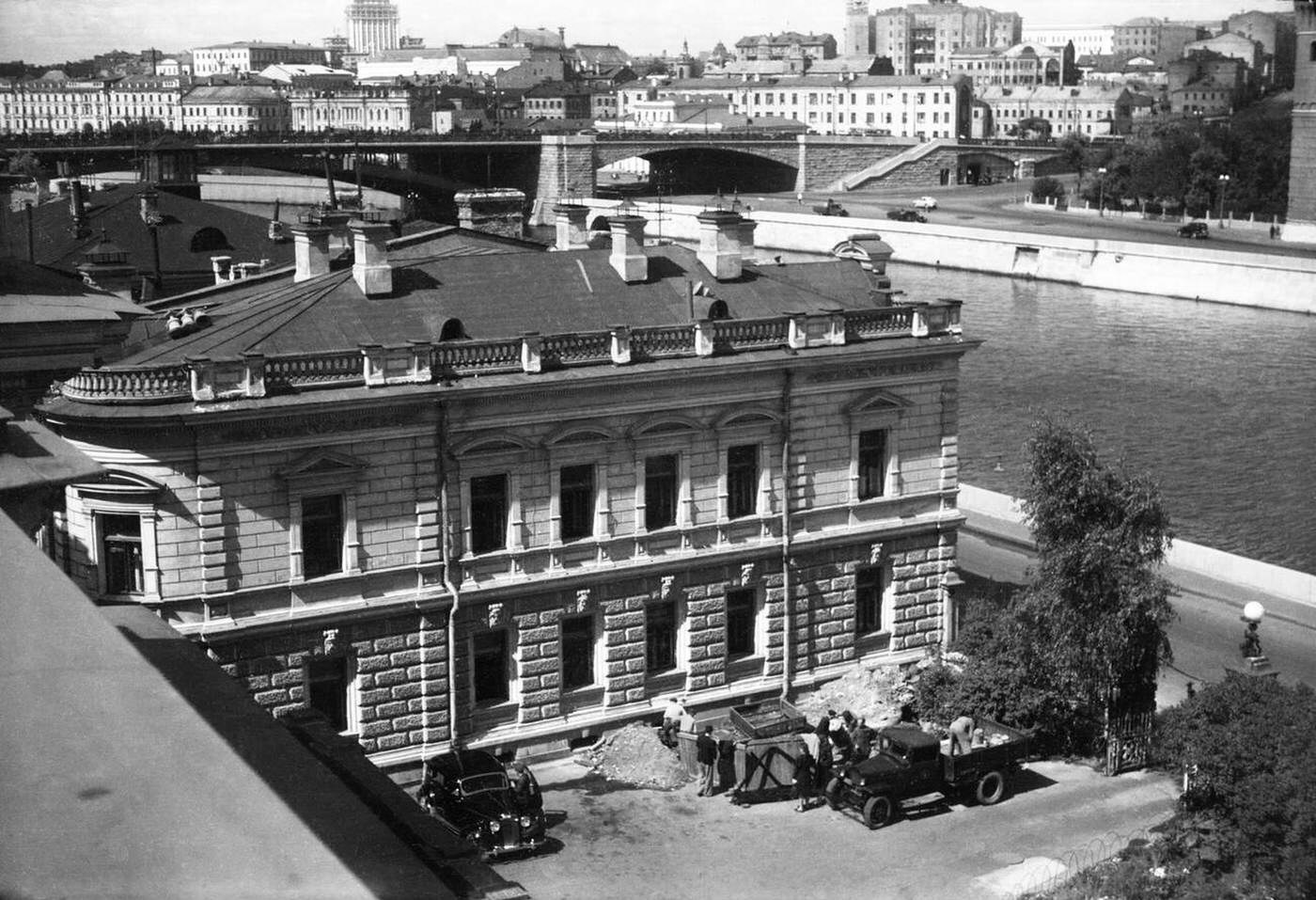

The state was also the universal landlord. Private ownership of property was abolished, meaning every citizen lived in state-owned housing. For millions, especially in the crowded cities, this meant life in a kommunalka, or communal apartment. A kommunalka was a large, pre-revolution apartment that had been subdivided. A single family was allocated one or two private rooms, which served as their bedroom, living room, and dining room. The kitchen, bathroom, and telephone in the hallway were shared by every family living in the apartment.

This forced proximity created an intense and unique social environment. On one hand, it could foster a deep sense of community and shared experience. On the other, it was a source of constant friction. Arguments over whose turn it was to clean the bathroom or who used too much electricity were a daily reality. Privacy was nonexistent. The thin walls and shared spaces also made it easy for the state to encourage neighbors to keep an eye on each other, reporting any suspicious or anti-Soviet talk.

The Economy of the Queue

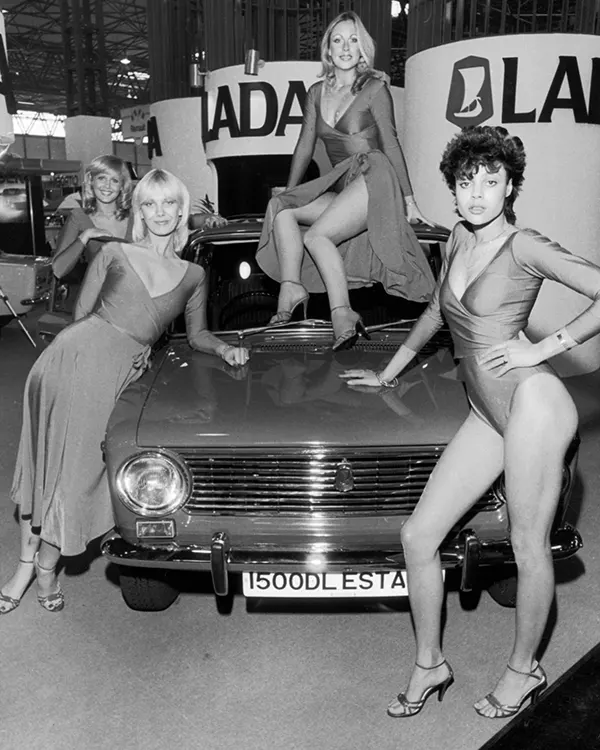

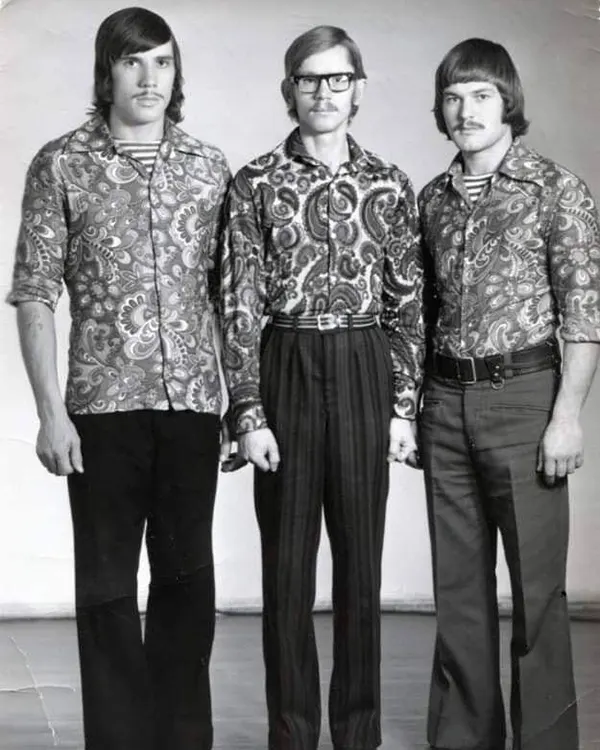

The Soviet Union’s centrally planned economy was excellent at producing tanks and sending satellites into space, but it was notoriously bad at making consumer goods. This created a permanent state of shortage, a condition known as defitsit. Basic items that people in the West took for granted—good shoes, quality sausage, toilet paper, decent furniture—were often in short supply.

This scarcity made queuing, or standing in line (ochered), a fundamental part of daily life. A Soviet citizen could spend several hours every day in various queues. The appearance of a line was an immediate signal to join it, often before you even knew what was being sold at the front. People carried a string bag called an avoska (a “what-if” bag) with them at all times, just in case they happened upon something for sale.

To navigate this system, people relied on a vast network of personal connections and favors known as blat. Blat was the unofficial currency that made the country run. A butcher might save a good cut of meat for a doctor who could get his child a faster appointment. A store manager might hold back a shipment of Finnish boots for a friend who could fix his car. This was the “second economy,” an illegal but essential shadow system that allowed people to acquire the goods the state failed to provide.

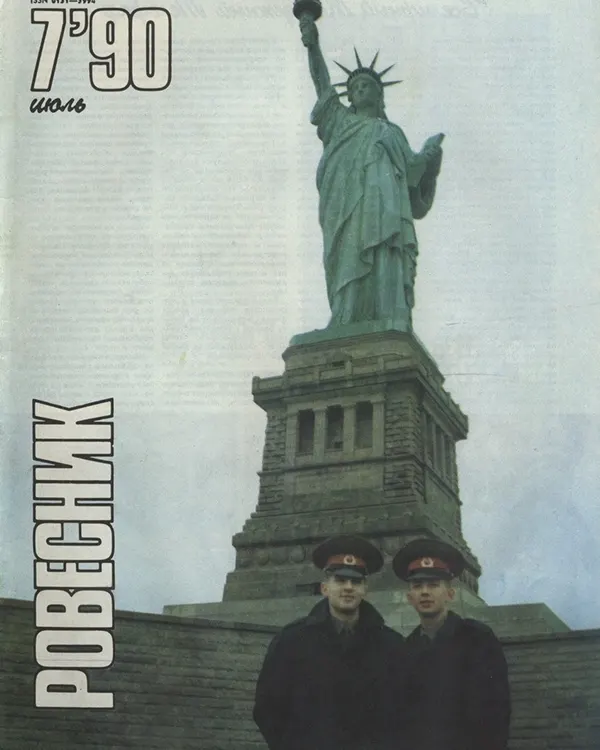

The Ideological Bubble

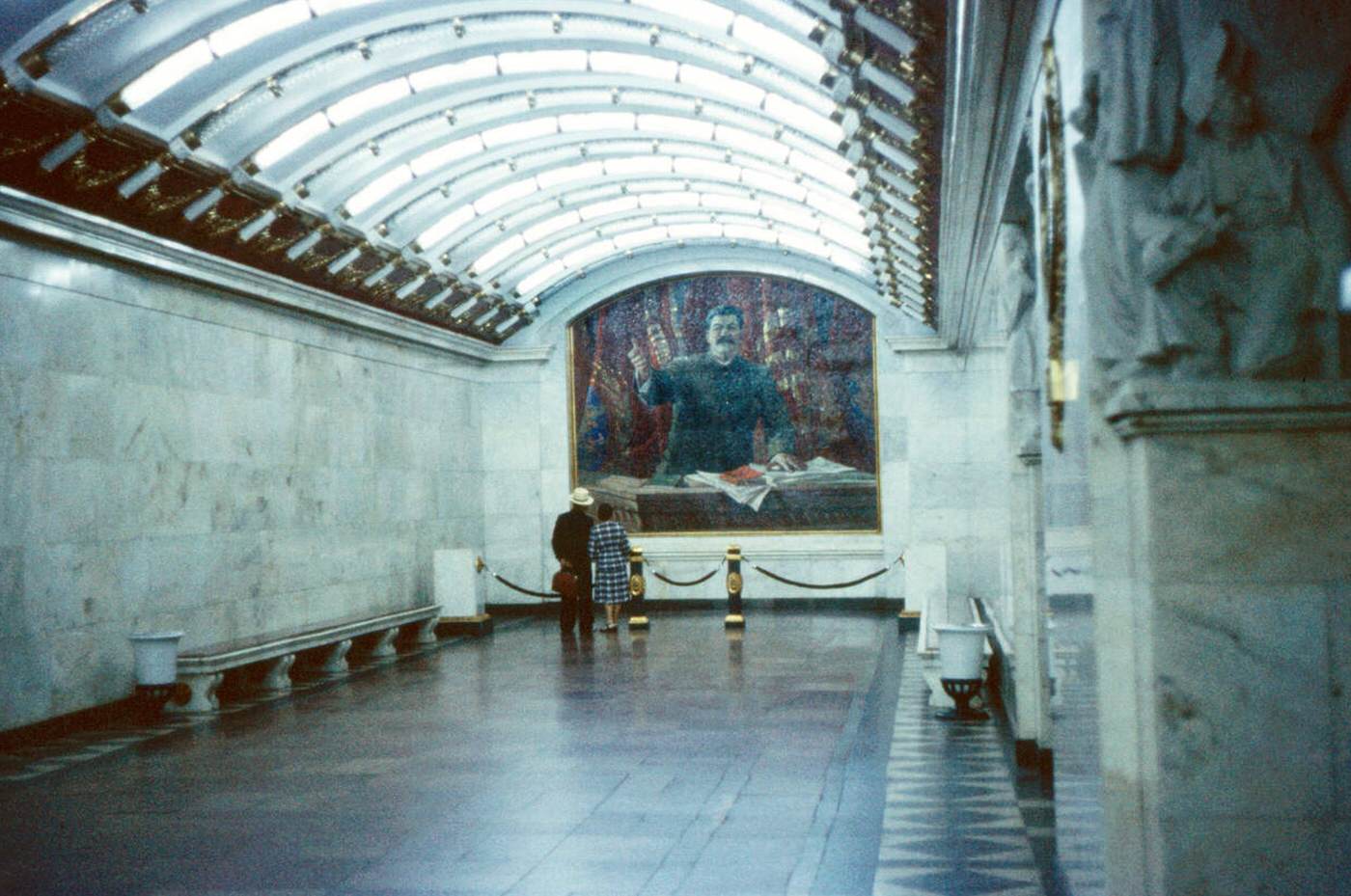

Life in the USSR was lived inside a bubble of communist ideology. Propaganda was everywhere. Giant portraits of Vladimir Lenin and current party leaders stared down from the sides of buildings. The state controlled all media. The two main newspapers were Pravda (which means “Truth”) and Izvestia (“News”), leading to a famous cynical joke: “There is no truth in Pravda and no news in Izvestia.”

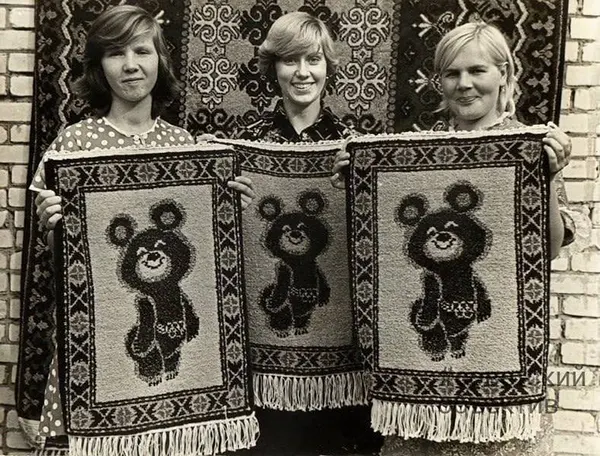

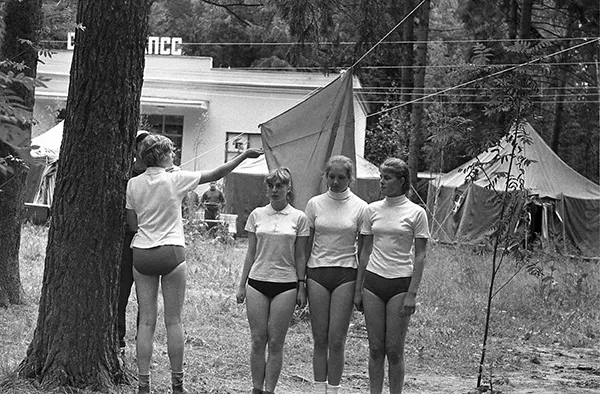

Indoctrination began in childhood. Children joined the Young Pioneers, wearing red scarves and pledging allegiance to the Communist Party. As teenagers, they graduated to the Komsomol (the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League). These organizations provided sports, camps, and social activities, but their primary purpose was to ensure generations of loyalty to the Soviet system.

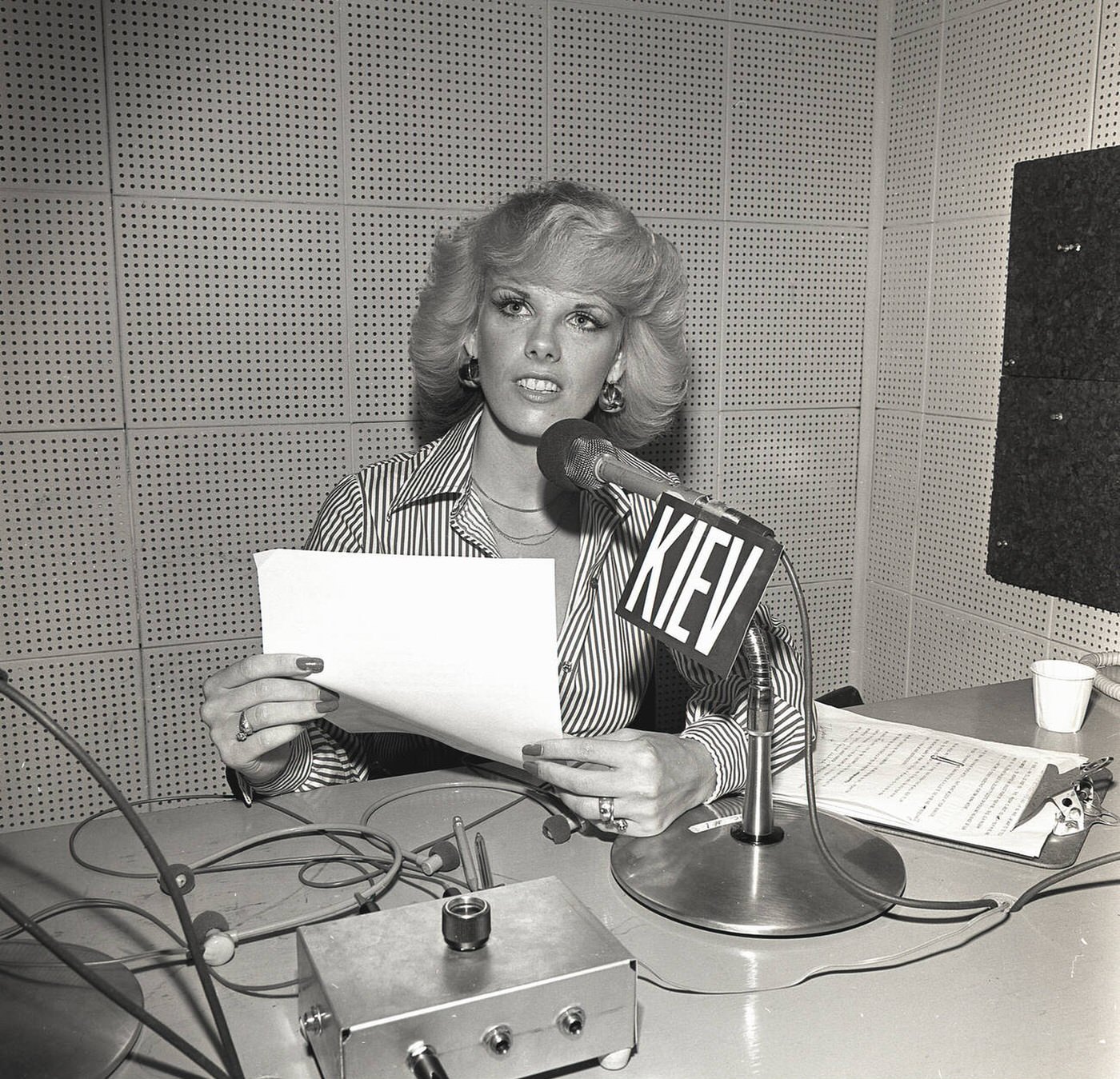

Overseeing all of this was the KGB, the state security agency. While the mass terror of the Stalinist era had faded by the 1960s and 70s, the fear remained. The state maintained a massive network of informants, and open dissent was crushed. Criticizing the government, telling a political joke too loudly, or even listening to a foreign radio broadcast could lead to a visit from the KGB, the loss of your job, or imprisonment.

The Soviet Escape

Life was not all grim queues and propaganda. The state also provided for leisure. The dacha was a cherished institution. This was a small, simple cottage in the countryside, often with a plot of land. For city dwellers, the dacha was a vital escape, a place to spend weekends breathing fresh air, socializing with friends, and, crucially, growing fruits and vegetables to supplement the food available in state stores.

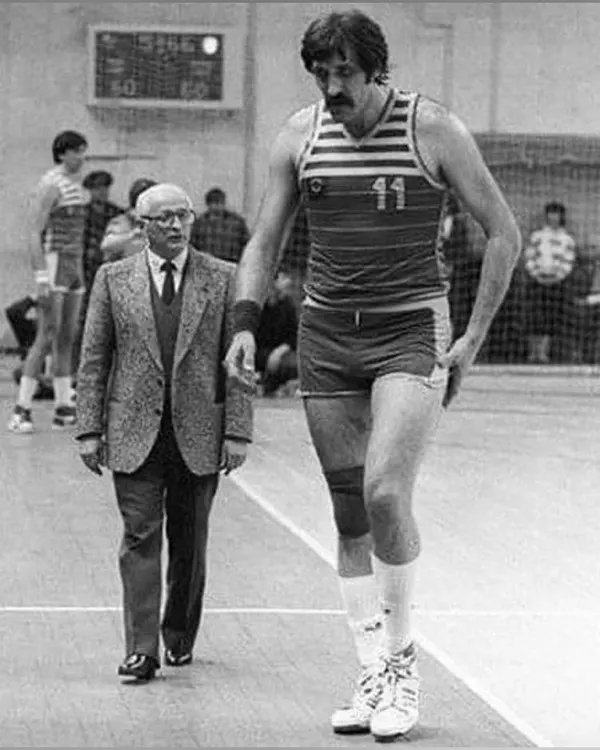

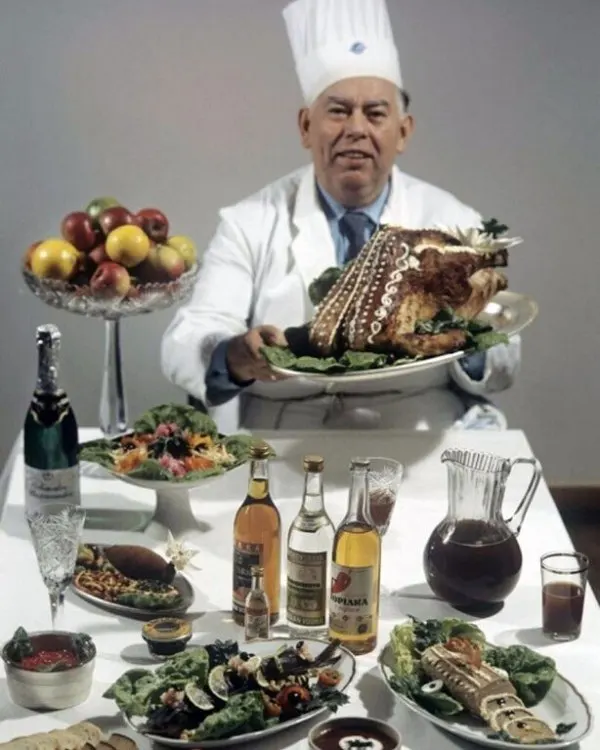

Entertainment was cheap and plentiful. Tickets to the world-renowned Bolshoi Ballet, the circus, or the cinema were heavily subsidized. The state poured resources into sports, and Soviet Olympic athletes and hockey players were treated as national heroes. Every worker was entitled to an annual vacation, often at a state-run sanatorium on the coast of the Black Sea. A family sits in their single, crowded room in a Moscow kommunalka. The father reads his copy of Pravda, its front page celebrating a record-breaking coal harvest in Siberia. The mother is in the shared kitchen down the hall, preparing a simple dinner of potatoes and cabbage. On a bookshelf, a prized pair of American blue jeans, acquired through a complicated chain of favors, is hidden behind the complete, state-approved works of Lenin.