The year was 1896, and Chicago was buzzing with a revolutionary energy. It wasn’t coming from a steam engine or a new factory, but from the silent, thrilling motion of two wheels. The city was at the absolute peak of America’s first great cycling craze, a full-blown obsession with what people called the “noiseless steed.” Bicycles were everywhere, weaving through city streets, challenging the supremacy of horse-drawn carriages and cable cars, and completely changing the way people lived, worked, and fell in love.

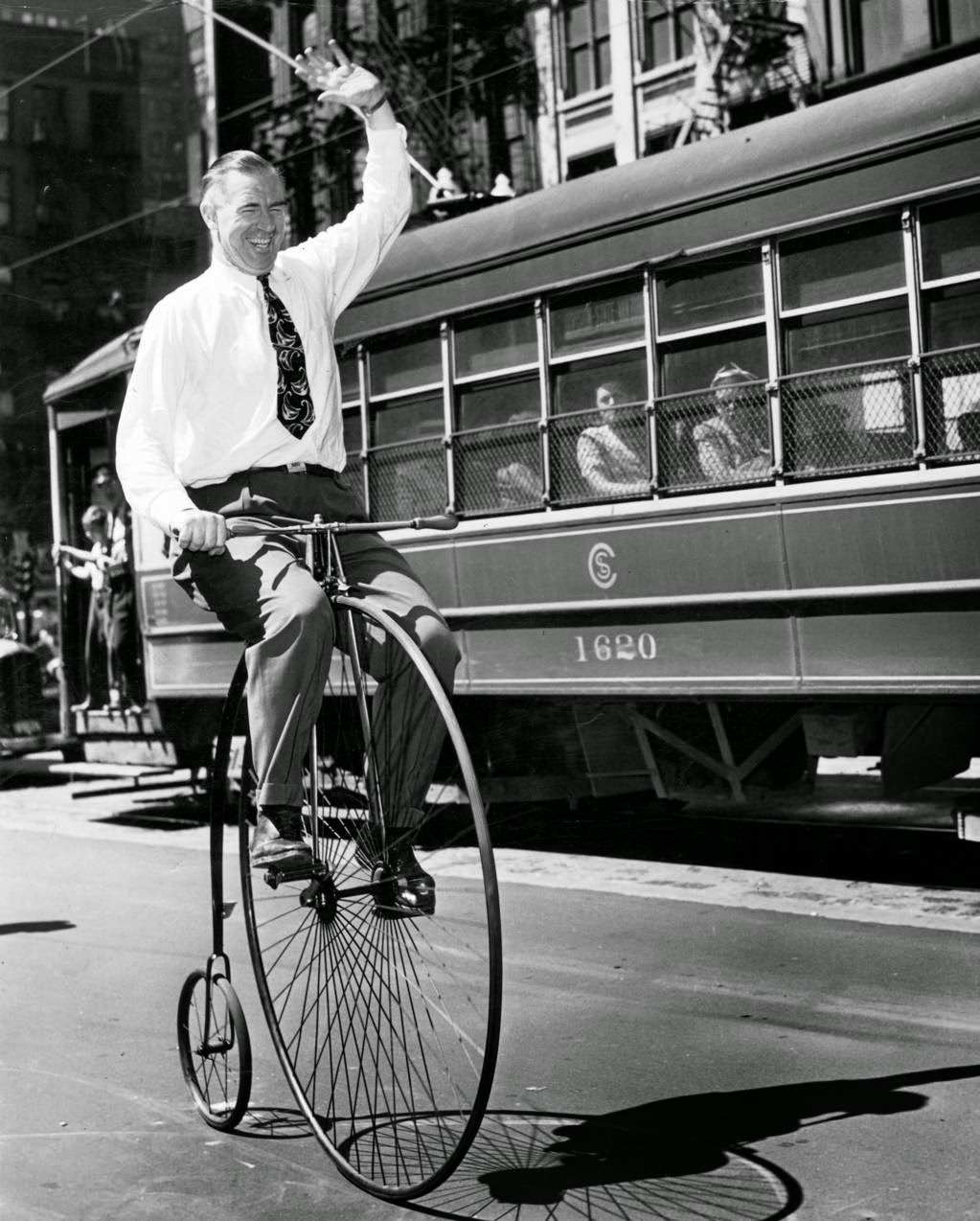

While clunky, high-wheeled penny-farthings had been around for a while, the 1890s craze was ignited by a groundbreaking invention: the safety bicycle. This new design featured two wheels of the same size, a chain-driven rear wheel, and air-filled pneumatic tires. Suddenly, cycling was no longer a dangerous circus act for athletic young men. It was safe, comfortable, and accessible to everyone.

Chicago didn’t just embrace the craze; it built it. The city rapidly became the manufacturing heart of the American bicycle industry. Factories churned out thousands of frames, wheels, and parts. The most famous of these manufacturers, Schwinn, was founded in Chicago in 1895, right at the height of the boom. The bikes being ridden across America were very often born in a Chicago factory.

Read more

The impact on society was immediate and profound. For women, the bicycle was nothing short of a tool of emancipation. It offered an unprecedented level of freedom and mobility. A woman could now travel across town on her own, without needing a horse, a chaperone, or a male relative. This newfound freedom sparked a revolution in fashion. The restrictive corsets and heavy, ground-dragging skirts of the Victorian era were impractical for cycling. Women began adopting more rational clothing, like shorter skirts or the controversial “bloomers”—baggy trousers gathered at the knee—which gave them the freedom to pedal.

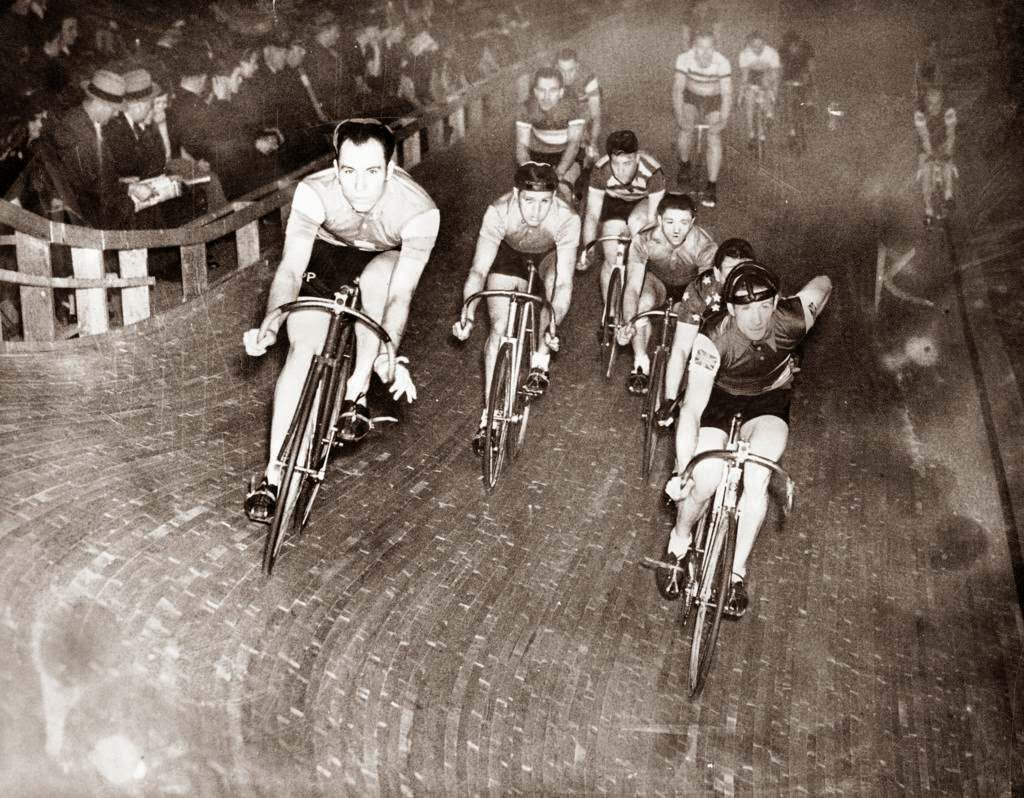

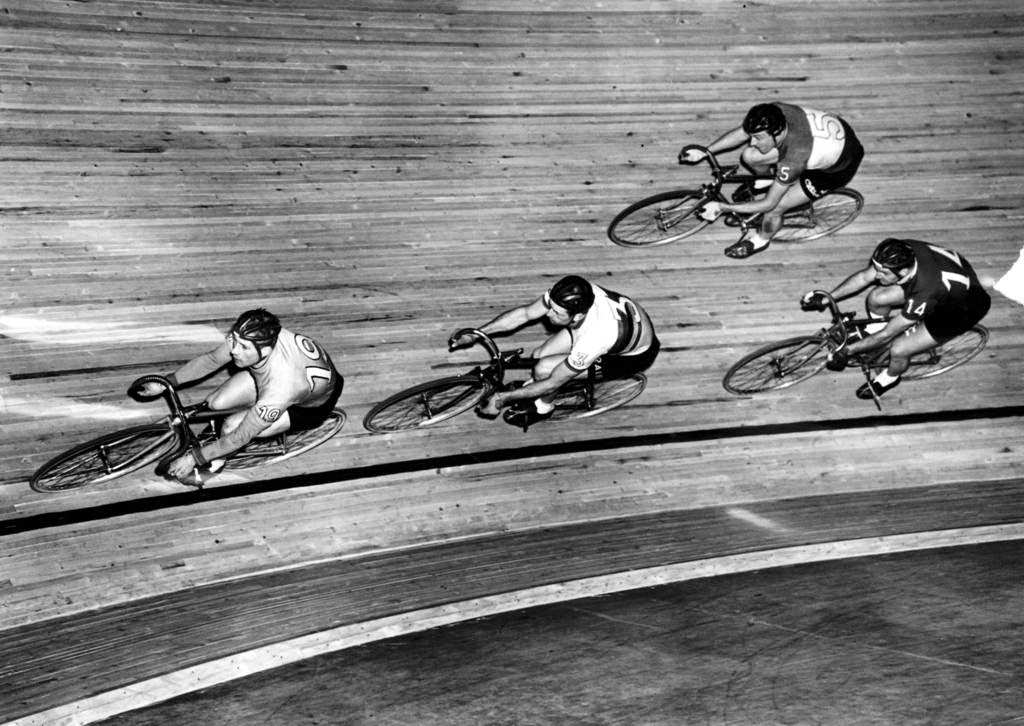

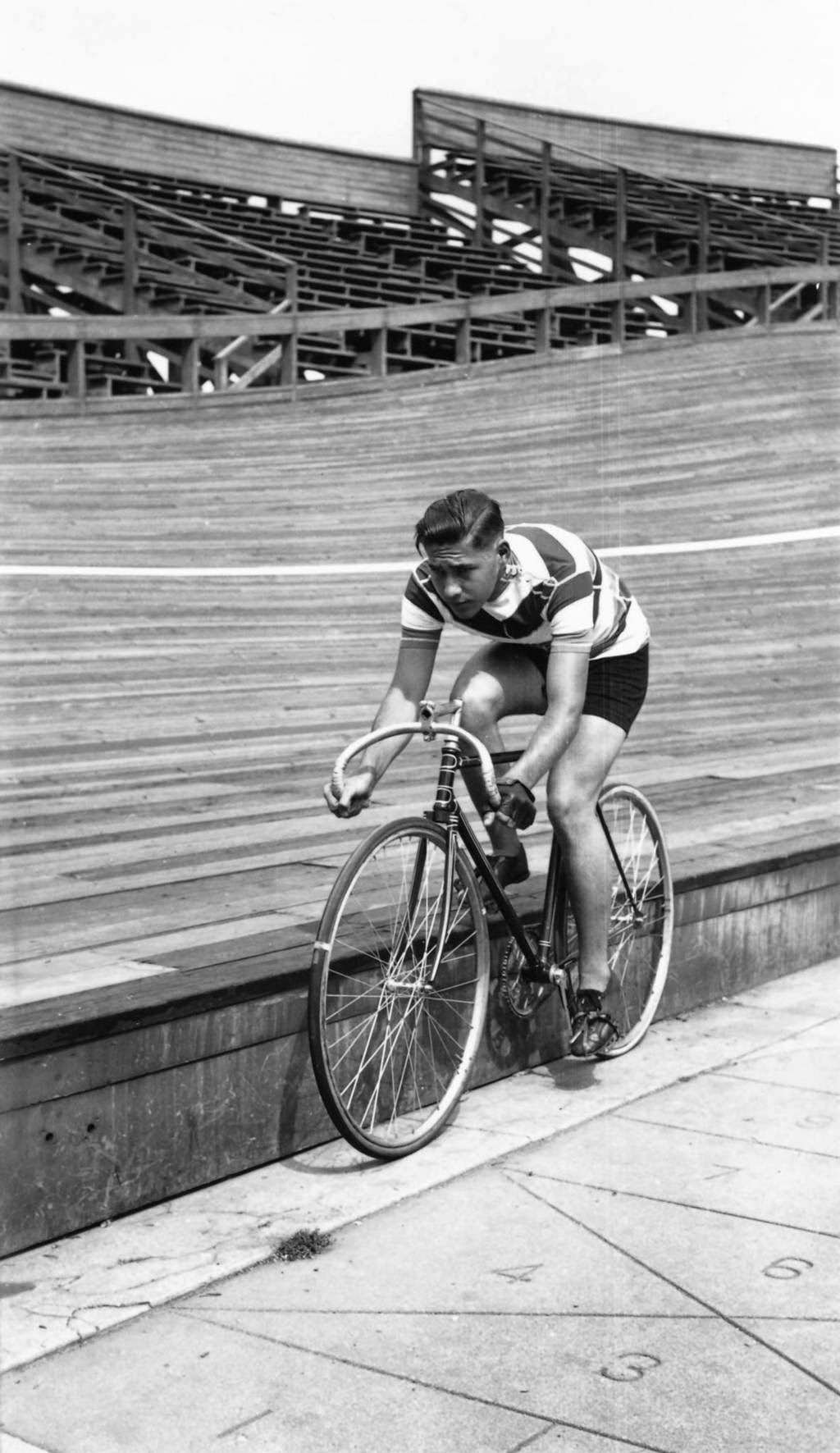

Social life was transformed. Hundreds of cycling clubs sprang up across Chicago. These clubs were the social hubs of their day, organizing massive group rides along the city’s grand boulevards like Drexel and Michigan Avenue. They held “century rides” (100-mile journeys) and sponsored thrilling, high-speed races that drew huge crowds. The bicycle created a new way for young people to meet, court, and socialize away from the watchful eyes of their parents.

This explosion of cyclists also led to conflict. The city’s streets were a chaotic mix of horse-drawn carts, electric streetcars, pedestrians, and now, thousands of swift, silent bicycles. Cyclists, often seen as arrogant “scorchers,” jostled for space. This tension fueled a powerful political movement. Cycling groups like the League of American Wheelmen became some of the most vocal advocates for better infrastructure, launching the “Good Roads” movement to demand paved streets, a benefit that would later be co-opted by the automobile.

From Craze to Utility: The Bicycle Finds a New Job

The turn of the century brought a new machine that would dethrone the bicycle as the ultimate symbol of personal freedom: the automobile. As cars became more affordable, the national obsession with the bicycle cooled. The bike’s role in American life shifted dramatically. It was no longer the exciting, revolutionary technology for the middle class.

Instead, the bicycle settled into a more practical, utilitarian existence. It became the primary mode of transportation for two main groups: children and blue-collar workers. The bicycle was the vehicle that gave kids their first taste of freedom, allowing them to explore their neighborhoods and ride to school. For thousands of factory workers in Chicago’s industrial districts, a sturdy, no-nonsense bicycle was the most reliable and affordable way to get to a shift.

During this era, Chicago’s own Schwinn solidified its place as an American icon. While other companies faded, Schwinn thrived by building incredibly durable and stylish bikes. In the 1930s, they introduced the Schwinn Aerocycle, a heavy, streamlined cruiser bike with balloon tires that could withstand years of daily use. This style of bike, with its built-in horns, headlights, and sturdy frames, became the classic American bicycle for the next three decades, a testament to Chicago’s enduring manufacturing legacy.

The Second Wind: The Ten-Speed Boom

For decades, the bicycle was seen primarily as a child’s toy or a worker’s tool. Then, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, something remarkable happened: adults rediscovered the bicycle, and a second, massive cycling craze swept the nation.

Several forces drove this “bike boom.” A new national focus on health and fitness made cycling an attractive form of exercise. A growing environmental consciousness, spurred by the first Earth Day in 1970, encouraged people to seek alternatives to polluting cars. The biggest catalyst, however, was the 1973 Oil Crisis. Suddenly, with skyrocketing gas prices and long lines at the pump, the humble bicycle looked like an incredibly smart, cheap, and efficient solution.

The star of this new boom was the ten-speed road bike. Inspired by lightweight European racing bikes, these models featured dropped handlebars, narrow tires, and a derailleur that allowed riders to shift through multiple gears. They were faster, lighter, and more versatile than the old cruisers. Schwinn once again dominated the market, with its Chicago-produced Varsity and Continental models becoming two of the best-selling bicycles of all time. Millions of Americans bought them.

Chicago’s cycling culture was reborn. The city’s Lakefront Trail, once a leisurely path, became a bustling highway for cyclists commuting to work or getting in their daily exercise. A new generation of advocates began pushing for dedicated bike lanes and safer streets. The bicycle was no longer just for kids; it was once again a serious and popular form of adult transportation and recreation. The craze that had started with the “noiseless steed” in the 1890s found a powerful second wind. This boom continued at a fever pitch for years, before eventually settling down as the urgency of the oil crisis faded and the bike found its new, more stable place in the life of the city.