The 1950 FIFA World Cup marked the return of the tournament after a 12-year break caused by World War II. Brazil hosted the event from June 24 to July 16, building massive new stadiums, including the Maracanã in Rio de Janeiro, which could hold over 200,000 spectators.

Thirteen teams competed, divided into four groups. Unlike modern formats, there was no knockout stage after the first round. Instead, the winners of each group advanced to a final round-robin group to determine the champion. Brazil, Uruguay, Sweden, and Spain made it to this decisive stage.

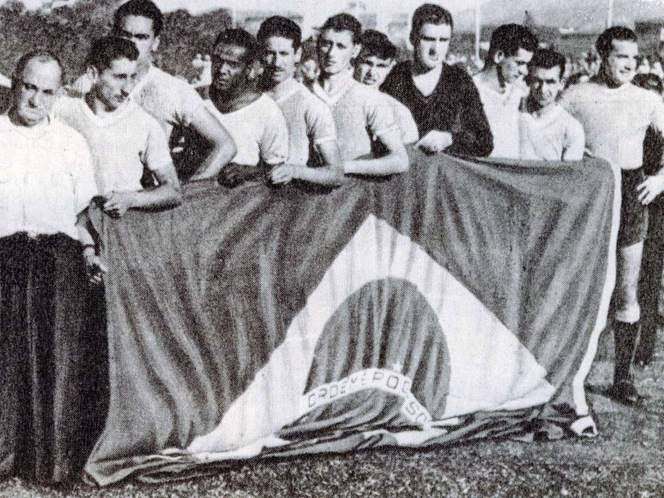

Brazil’s squad entered the tournament with high expectations. They had a powerful attack featuring Zizinho, Ademir, and Jair, and they dominated their early matches. In the final round, Brazil crushed Sweden 7–1 and then dismantled Spain 6–1, creating an atmosphere of national confidence before the decisive match against Uruguay.

Read more

The final game took place on July 16, 1950, at the Maracanã. A record-breaking crowd filled the stadium, with most expecting a Brazilian victory. Uruguay needed to win to claim the title, while a draw would be enough for Brazil. Brazil scored first through Friaça early in the second half, sending the crowd into celebration.

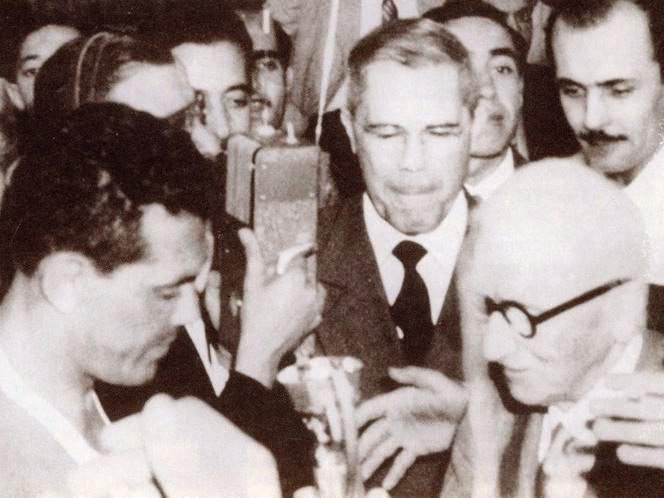

Uruguay responded with precision. Juan Alberto Schiaffino equalized in the 66th minute. In the 79th minute, Alcides Ghiggia broke through on the right wing and scored the winning goal past goalkeeper Moacir Barbosa. The stadium fell silent, and Uruguay secured a 2–1 victory.

This shock result became known as the Maracanazo — the “Maracanã Blow.” It stunned Brazil and became one of the most famous upsets in sports history. Ghiggia later remarked that only three people had silenced the Maracanã: Frank Sinatra, the Pope, and himself.

Attendance figures, playing styles, and even political tensions made the 1950 World Cup unique. It was the last tournament without a final match in the modern sense, and the last where goal difference wasn’t used to separate teams in the group stage. It also introduced the world to the idea that football could produce moments as dramatic and devastating as any other event in national life.