World War II was not just a war of tanks, planes, and battleships. It was a war of images. For the first time, a global conflict was documented on an epic scale, not by painters or sketch artists, but by a new breed of soldier and journalist armed with a camera. These photographers waded onto bloody beaches, flew through flak-filled skies, and marched into liberated concentration camps. They were not safe observers watching from a distance; they were in the thick of the action, often unarmed, carrying the heavy burden of showing the world the face of its most destructive war.

A New Breed of Soldier, a New Kind of Journalist

The photographers of WWII were not a single, unified group. They came from different backgrounds and served different functions, spread across every theater of the war.

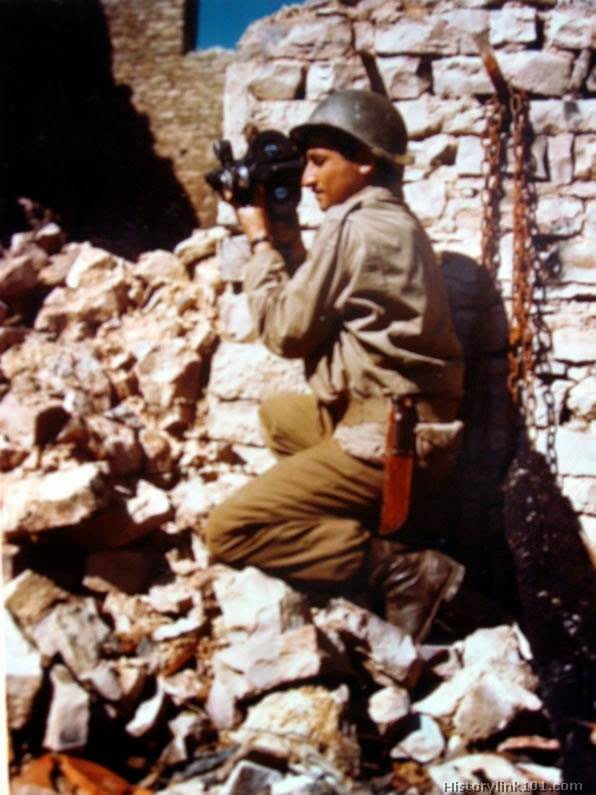

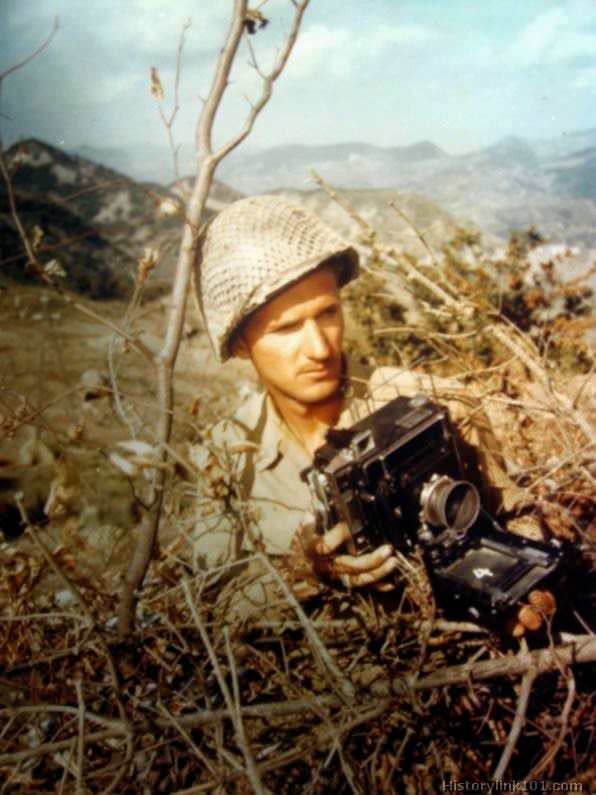

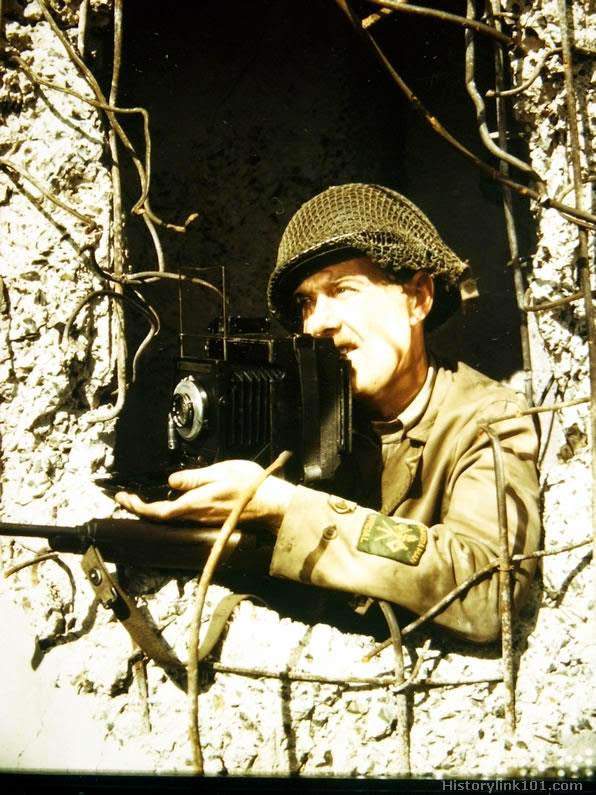

The most numerous were the official military combat photographers. These were enlisted men, part of units like the U.S. Army Signal Corps or the U.S. Navy’s photographic units. They were trained soldiers who also knew how to handle a camera. Their primary job was to document military operations for official records, training manuals, and intelligence analysis. Every major invasion, battle, and piece of new equipment was recorded by these servicemen. Their photos were often practical and direct, meant to inform command rather than to stir emotions.

Read more

Then there were the civilian war correspondents and photojournalists. These were the men and women working for major publications like LIFE magazine, Time, and the Associated Press. They were accredited by the military, which gave them access to the front lines, but they had more freedom to tell the human story of the war. They focused on the faces of the soldiers, the devastation of cities, and the emotional toll of the conflict. It was this group that produced many of the war’s most iconic and enduring images.

A third front of photography existed far from the battlefields. On the home front, photographers like Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams documented the societal shifts caused by the war. Adams, famous for his majestic landscapes, took on a project to photograph the lives of Japanese Americans unjustly forced into internment camps, creating a powerful and somber record of wartime injustice.

The Gear That Captured History

There were no digital cameras, no smartphones, no instant uploads. Every single photograph taken during WWII was a complex physical process, often performed under the most difficult conditions imaginable.

The workhorse camera for many press photographers was the Graflex Speed Graphic. It was big, heavy, built like a tank, and used 4×5 inch sheet film. Each photo required loading a new sheet, making it slow to operate. But it produced large, incredibly detailed negatives, perfect for newspaper printing.

For photographers who needed to be more mobile and discreet, the smaller 35mm cameras were a revelation. The German-made Leica and Contax cameras were favorites. They were small, fast, and allowed a photographer to shoot a roll of 36 pictures quickly, capturing sequences of action that were impossible with the larger cameras. These were the cameras that got you close.

Getting the shot was only half the battle. Film had to be protected from heat, moisture, and damage. After shooting, the rolls or sheets had to be transported, often by plane or jeep, thousands of miles back to a darkroom where they could be developed and printed. Every single shot a photographer took was a precious, calculated risk.

The Ultimate Price

These photographers were not invincible. They faced the same dangers as the soldiers they documented. They were shelled, shot at, and caught in crossfire. A photographer carrying a camera could be seen by an enemy sniper as a valuable target, someone gathering intelligence. Dozens were killed in action. Robert Capa survived WWII, only to be killed after stepping on a landmine in 1954 while covering the First Indochina War. He died living by his own words, getting as close as possible. In foxholes and on rolling seas, in the bellies of bombers and on the rubble of ruined cities, they raised their cameras to their eyes, focused through the chaos, and captured the fleeting, terrible, and essential moments of human history.