New York City in the 1910s was a place of intense energy and transformation. Its population surged past five million, driven by a massive wave of immigration and the promise of work. The decade saw the city’s skyline reach new heights while its streets buzzed with social change, new forms of entertainment, and the daily struggles of millions packed into its neighborhoods.

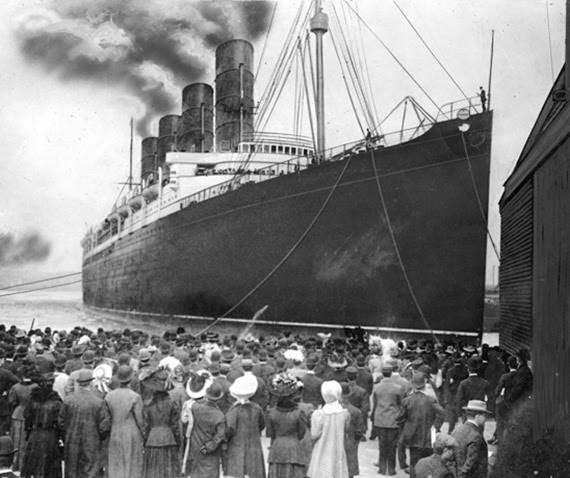

The Gateway to America

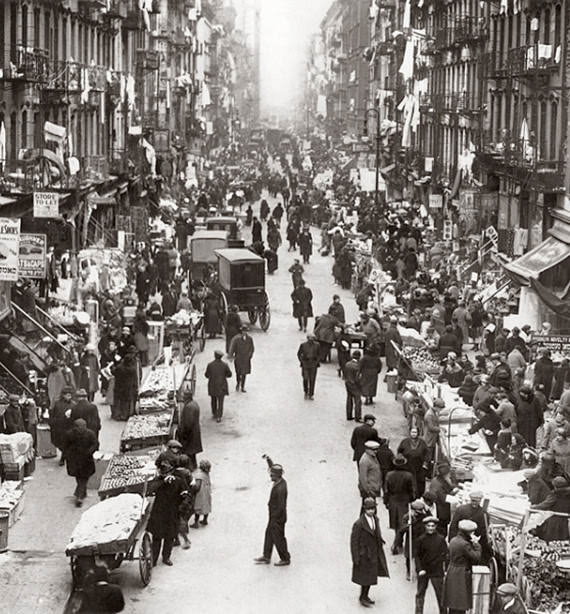

For hundreds of thousands of immigrants, the first sight of America was the Statue of Liberty and the processing halls of Ellis Island. Between 1910 and 1914, immigration reached its peak, with people arriving mainly from Southern and Eastern Europe, including Italy, Russia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After passing medical and legal inspections on the island, these newcomers settled in ethnic enclaves across the five boroughs.

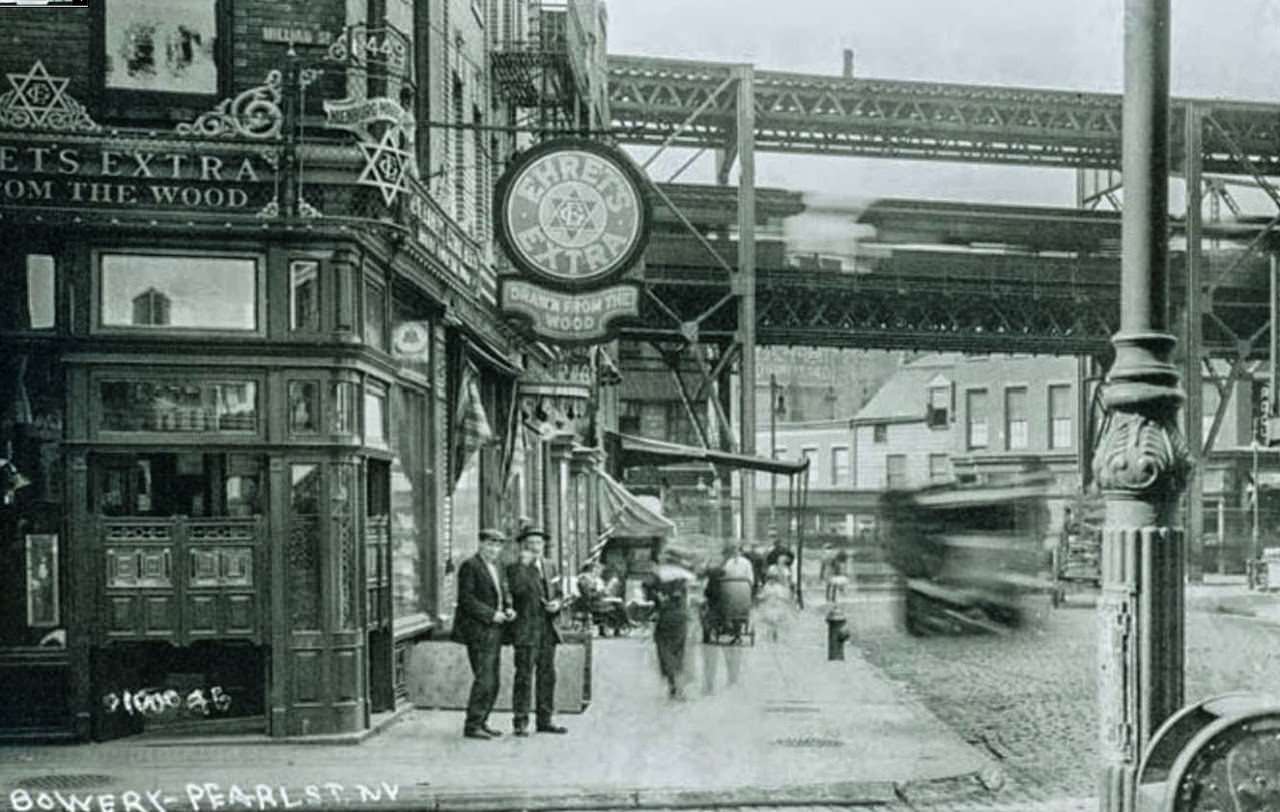

Many found themselves in the tenement apartments of the Lower East Side. These buildings were often overcrowded, with entire families living in small, cramped spaces that frequently lacked adequate light, ventilation, and private sanitation. The streets below served as a communal living room, market, and playground, filled with the sounds of different languages and the smells of pushcart foods. For these new arrivals, work was an immediate necessity. Many men found jobs as laborers on construction projects or as factory workers, while women and children often worked in the city’s bustling garment industry.

Read more

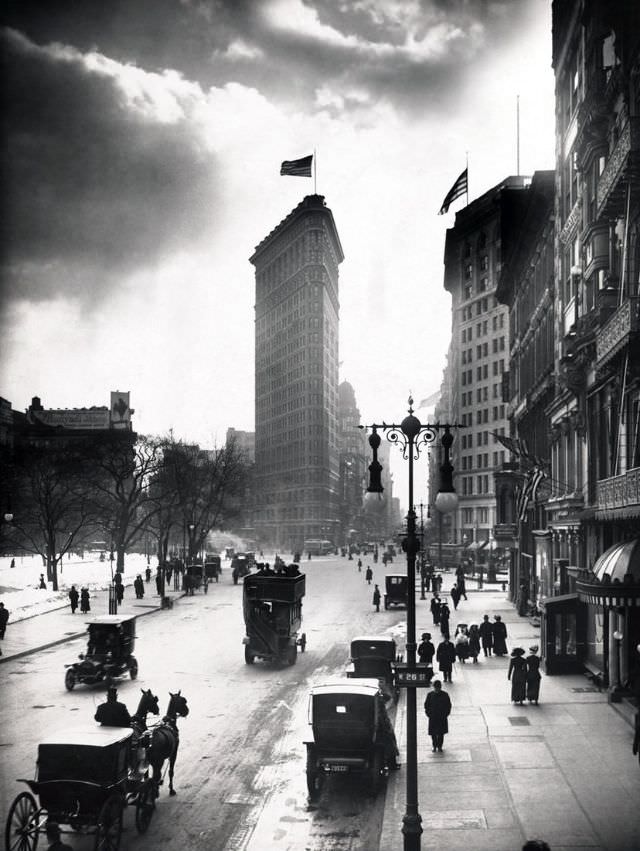

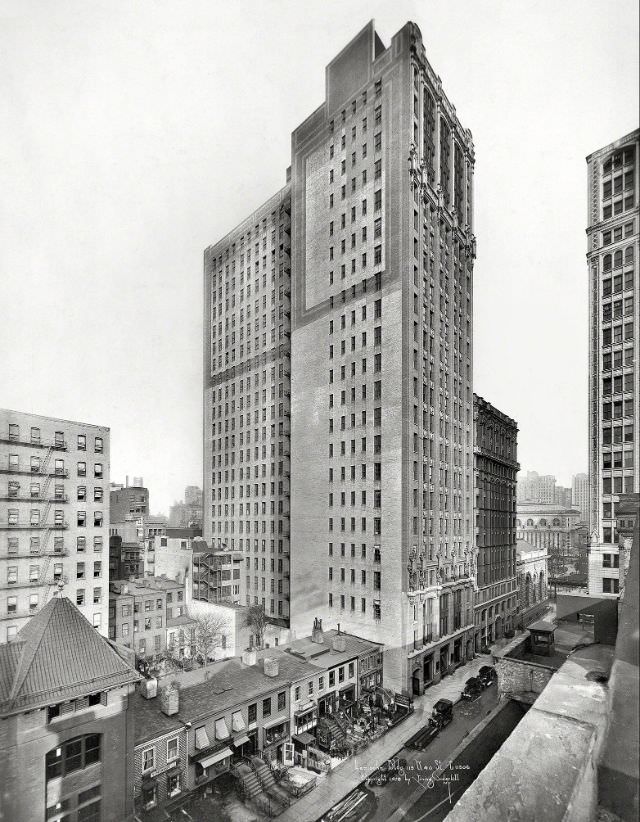

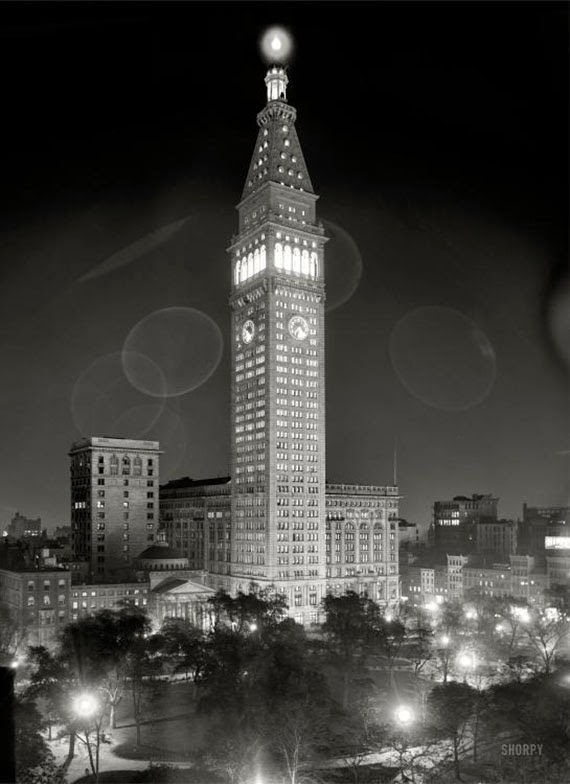

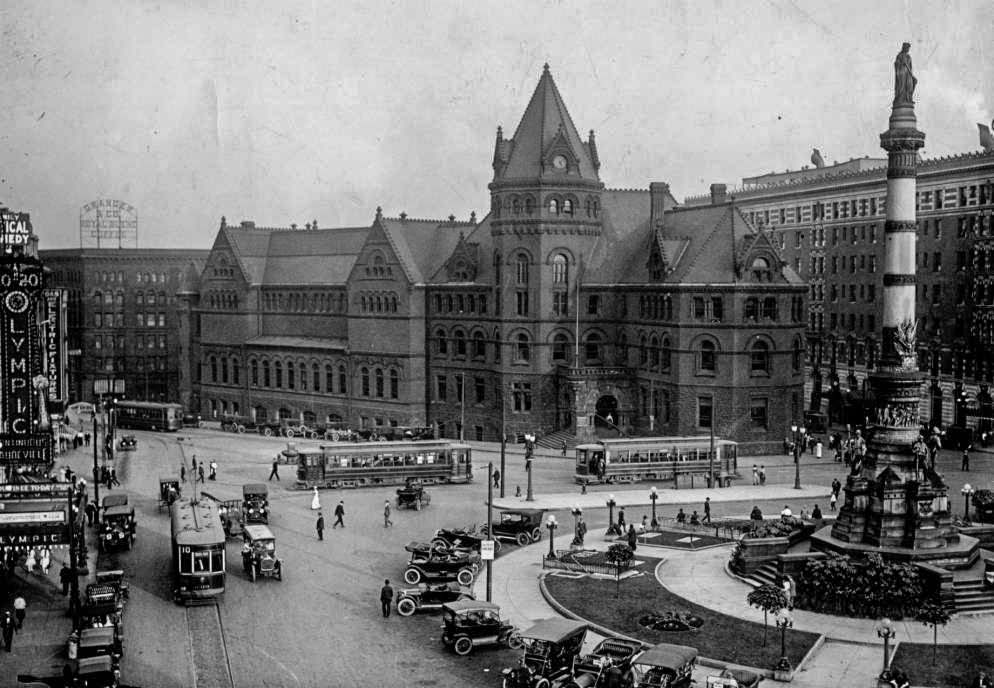

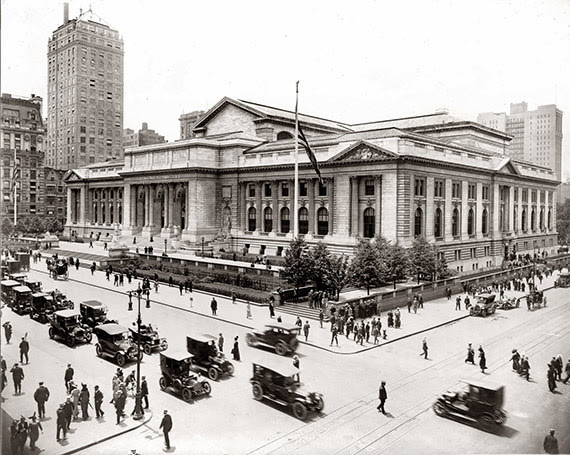

The Rise of a Modern Skyline

The 1910s were a critical decade for the architectural development of New York. The city was in a race to build taller, more impressive structures. In 1913, the Woolworth Building was completed on Broadway in Lower Manhattan. Standing at 792 feet, it was the tallest building in the world at the time, a cathedral-like skyscraper celebrated for its Gothic design and technological achievement.

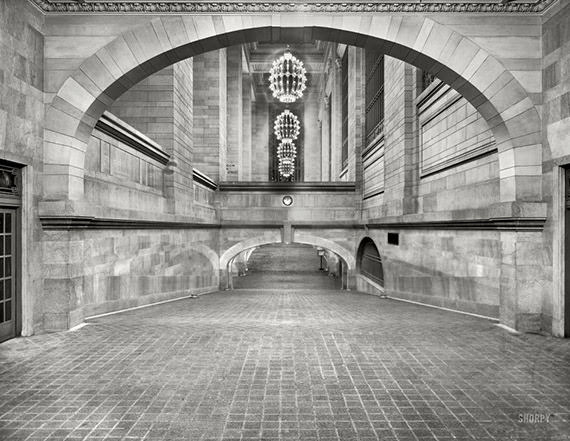

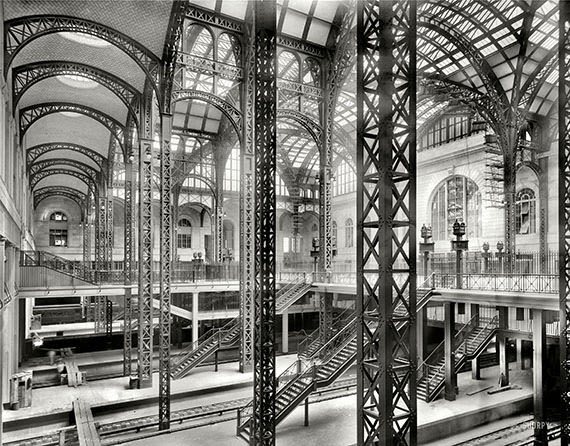

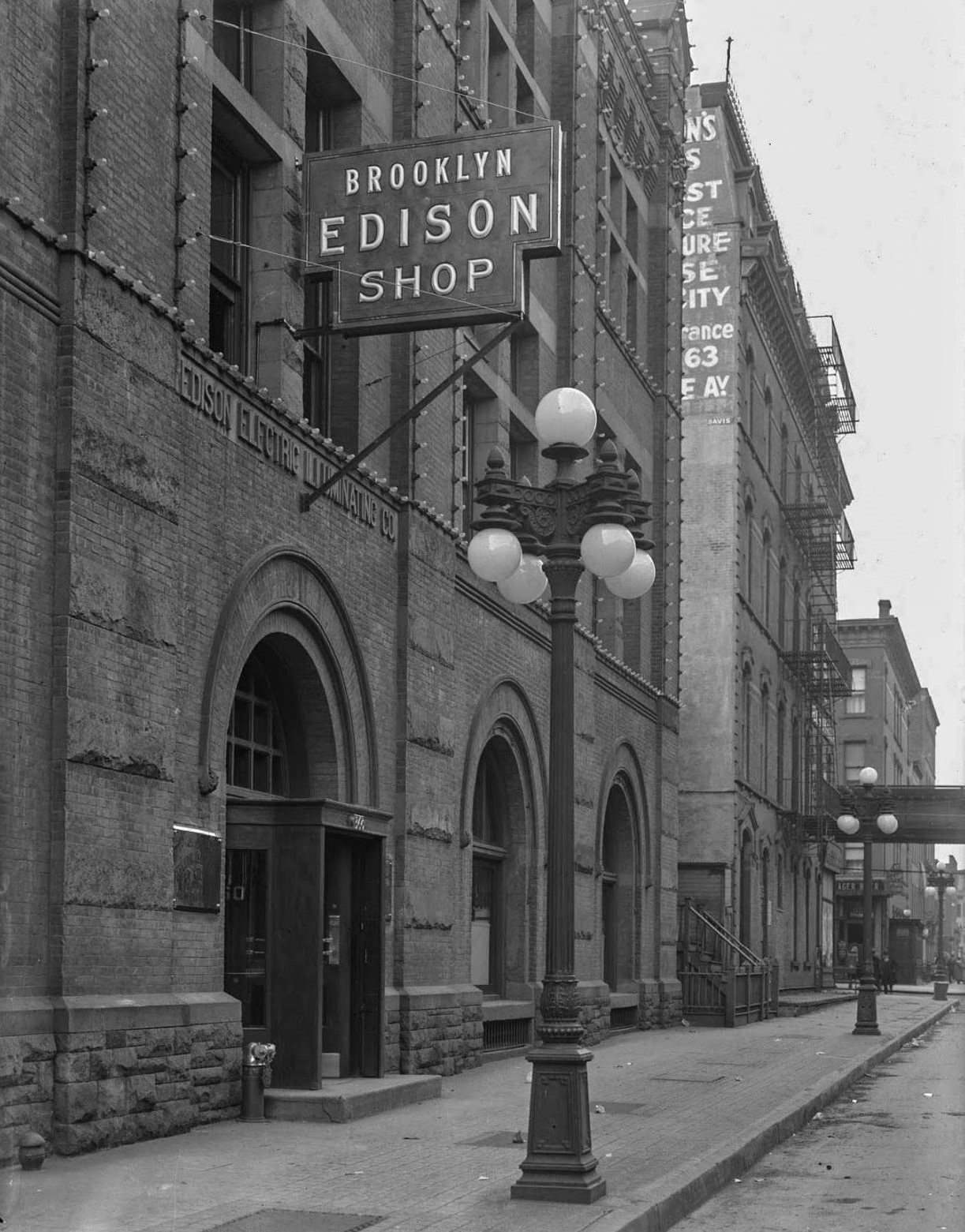

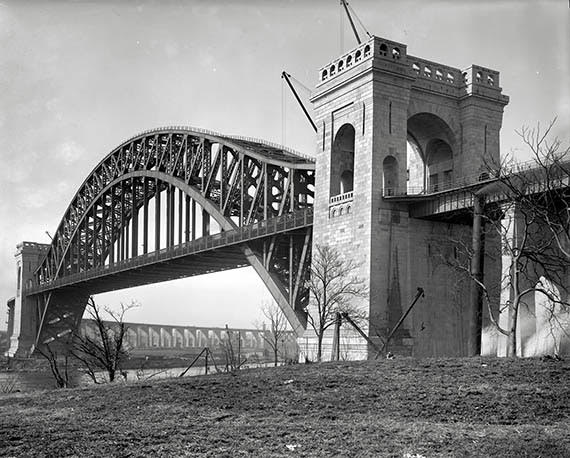

Transportation infrastructure also took a massive leap forward. Grand Central Terminal opened its doors on February 2, 1913, after a decade of construction. It was more than just a train station; it was a grand civic space with a celestial-painted ceiling, marble staircases, and innovative ramp systems instead of stairs. Below ground, the subway system was rapidly expanding. The Dual Contracts of 1913, an agreement between the city and two private subway operators, led to the construction of hundreds of miles of new track, connecting distant boroughs like the Bronx and Brooklyn to the commercial heart of Manhattan.

Labor, Tragedy, and Reform

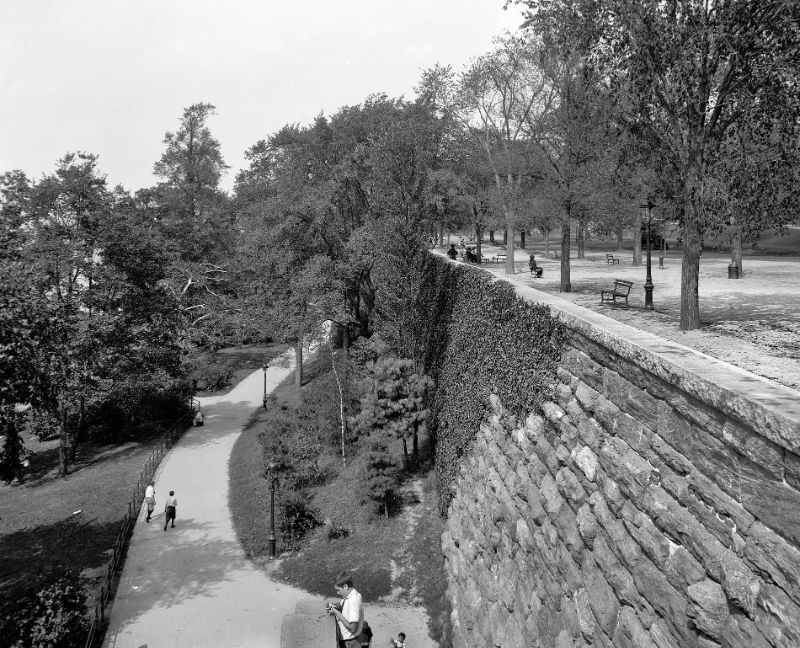

The city’s industrial might relied on a vast workforce that often labored in dangerous conditions for low pay. The garment industry, a major employer, was notorious for its “sweatshops.” This reality was brought into sharp focus on March 25, 1911, by the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. A fire broke out on the upper floors of a building near Washington Square Park, trapping the young immigrant women who worked there. Locked exit doors and inadequate fire escapes resulted in the deaths of 146 workers. The tragedy horrified the city and the nation, leading to a wave of new legislation that improved factory safety standards, working hours, and labor laws.

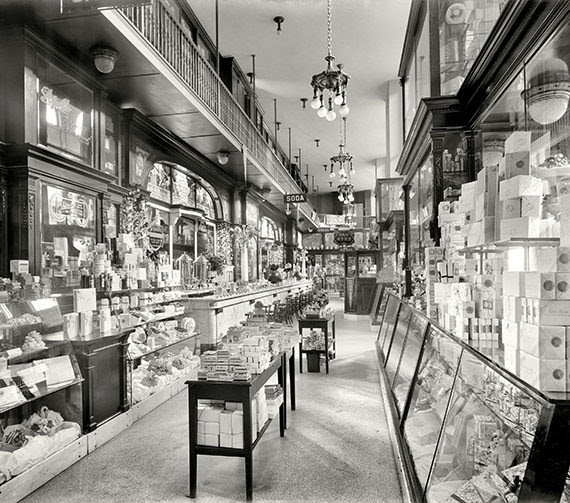

New Rhythms and a Shifting Culture

The decade was also a time of vibrant cultural creation. The area around West 28th Street became known as Tin Pan Alley, the center of the American music publishing industry. Here, songwriters and “song pluggers” churned out popular tunes that were sold as sheet music across the country. On Broadway, lavish theatrical productions became a staple of middle-class entertainment.

In the art world, the 1913 Armory Show, officially The International Exhibition of Modern Art, introduced many Americans to the radical new styles of European artists like Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Marcel Duchamp. The show was a shock to the public and critics, challenging traditional ideas of what art could be. Meanwhile, the women’s suffrage movement was gaining significant momentum. Activists organized large-scale parades on Fifth Avenue, with thousands of women marching to demand the right to vote, a right they would win in New York State in 1917.