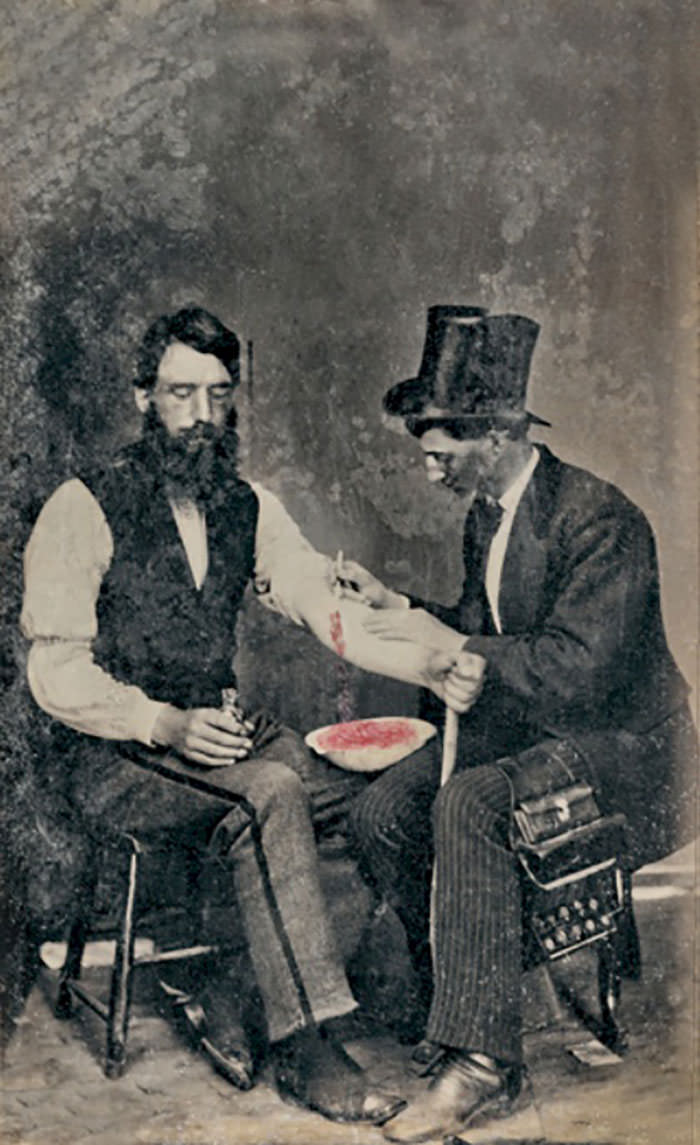

Bloodletting, one of the oldest medical practices, has a history that spans over 3000 years, with roots in ancient Egypt. This procedure gained widespread popularity in medieval Europe, where it was employed as a treatment for various ailments such as smallpox, epilepsy, and the plague. Surprisingly, the practice continued well into the 19th century and can still be found in some limited applications today.

As the 19th century drew to a close, the medical community began to recognize the risks associated with bloodletting and questioned its efficacy as a treatment. Doctors eventually acknowledged that draining a patient’s blood could be hazardous and offered few tangible health benefits. Some of the potential risks of bloodletting include cardiac arrest, excessive blood loss, dangerously low blood pressure, and anemia. Moreover, the procedure can also lead to infections due to unsanitary conditions and instrum

There were several factors that contributed to our understanding of how the body works and what causes disease. For a long time, it was believed that the body contained four liquids: black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. It is essential for these to be in balance for one to be healthy. It was believed that blood contained a small amount of all three, so it could theoretically be used for diagnosing anything. The humours could be balanced by taking some blood. That’s why it made sense to people. Germ theory was not widely accepted until the 19th century. What kept it going was that it was relatively harmless compared to many other methods of “treating” disease. The majority of people get frustrated when they go to the doctor and are told they have a virus, go home and it will get better, and there is nothing we can do to speed up your recovery (obviously, we can treat symptoms, but it’s your body doing its thing to get you to the point where you don’t need that treatment). It is easy to imagine that when you have an idea that is simple and relatively safe, and you’ve seen people get better after it before, even if some didn’t, then you give it a try. Oh look, they got better. It must have been the blood letting, not that if I had just left them alone they would have gotten better.

There is a close connection between bloodletting and the idea of humours at the heart of medicine, at least in Europe. A person’s health is determined by the balance of the four humours in the body, which are blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. The long-term use of this approach to medicine in different parts of the world shows how appealing it can be. The holistic approach treats both the body and the mind, and includes not just the physician’s treatment but also the patient’s lifestyle. Historically, it had authority dating back to the ancient Greeks. Any alternative theory that challenges well-established interests and long-established practices is usually hard to shift because it explains less than the old theory. When you introduce germ theory (disease is caused by tiny creatures too small to be seen? how convenient for your theory…), how does that affect mental health and diet? Before the 19th century, there were no rival theories strong enough to challenge and replace the system of humours; the necessary practical and theoretical tools did not exist (e.g. high quality microscopes, control trials). The practice of bloodletting itself was so common because blood was not just a humour itself, but could also contain other humours. In the right place, blood can draw out other humours or move them to or away from a particular part of the body. Also, it helped that the practice was very visible: there was no doubt that something was happening.

It’s probably not medical; if you look at the cognitive biases we all have, we’re drawn to things that give us a sense of purpose and agency So, when faced with the choice of doing nothing and waiting, or doing something that has no effect, most people feel better doing something because it gives them a sense of agency. Sadly, this tendency to do something regardless of whether it helps or makes things worse isn’t limited to quack medicine.